The Second Successful American Coup d’état: The JFK Assassination

October 18, 1962, in the Oval Office: President Kennedy, Soviet Deputy Minister Vladimir S. Seyemenov, Ambassador of the USSR Anatoly F. Dobrynin, and Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrel Gromyko. Robert L. Knudson, US National Archives and Recordings Administration, 1962.

We are not going to delve into any of the JFK conspiracy theories, such as the magic bullet or the multiple gunmen. The grassy knoll and the mafia will be left to Jim Garrison and Oliver Stone, because it doesn’t matter how many bullets or how many gunmen shot the president of the United States, or even if Lee Harvey Oswald was actually involved. The fact remains that JFK’s presidential motorcade is the only procession in the history of the known world where the victim was led to the assassin—a man allegedly went to his place of work on the sixth floor of an office building, took a coffee break, and a little later allegedly went to a window on the same floor and shot and killed a world leader handed to him on a silver platter in an open motorcade.

Roughly six weeks prior to the November 22, 1963, assassination, Lee Harvey Oswald applied for a job at the Texas School Book Depository that overlooked Dealey Plaza. Three days prior on November 19, both the Dallas Morning News and the Dallas Times-Herald published the president’s motorcade route from Love Field to the Trade Mart where he was to speak. Oswald presumably read one of these announcements that the man he allegedly hated enough to kill would be six floors below him in less than seventy-two hours. Lee Harvey Oswald, the only alleged assassin in the history of the world who didn’t have to pursue his victim.

Conspiracy theorists waste their efforts attempting to prove whether or not Oswald fired the shots that killed JFK, or if there were multiple gunmen. They are moot points. The key is that if Oswald, alone or with other conspirators, had not succeeded in killing him, President Kennedy would never have made it to a second term anyway:

• Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK and Khrushchev were in negotiations on a limited nuclear test-ban treaty that would have severely hindered the military-industrial machine. Many generals and top government officials, especially within the CIA, considered this to be an act of treason. They were preparing for escalated hostilities in Vietnam and the overthrow of Castro in Cuba, yet their president was preparing for peace. On June 10, 1963 (less than five months prior to his death), Kennedy addressed the graduating class of American University. In a powerful plea, he said, “Every thoughtful citizen who despairs of war and wishes to bring peace, should begin by looking inward. . . . War makes no sense in an age when the deadly poisons produced by a nuclear exchange would be carried by wind and water and soil and seed to the far corners of the globe and to generations yet unborn. . . .” And finally, Kennedy stated, “I am taking this opportunity, therefore, to announce two important decisions in this regard. First: Chairman Khrushchev, Prime Minister Macmillan, and I have agreed that high-level discussions will shortly begin in Moscow looking toward early agreement on a comprehensive test ban treaty. Our hopes must be tempered with the caution of history—but with our hopes go the hopes of all mankind. Second: To make clear our good faith and solemn convictions on the matter, I now declare that the United States does not propose to conduct nuclear tests in the atmosphere so long as other states do not do so. We will not be the first to resume. Such a declaration is no substitute for a formal binding treaty, but I hope it will help us achieve one. Nor would such a treaty be a substitute for disarmament, but I hope it will help us achieve it.”122

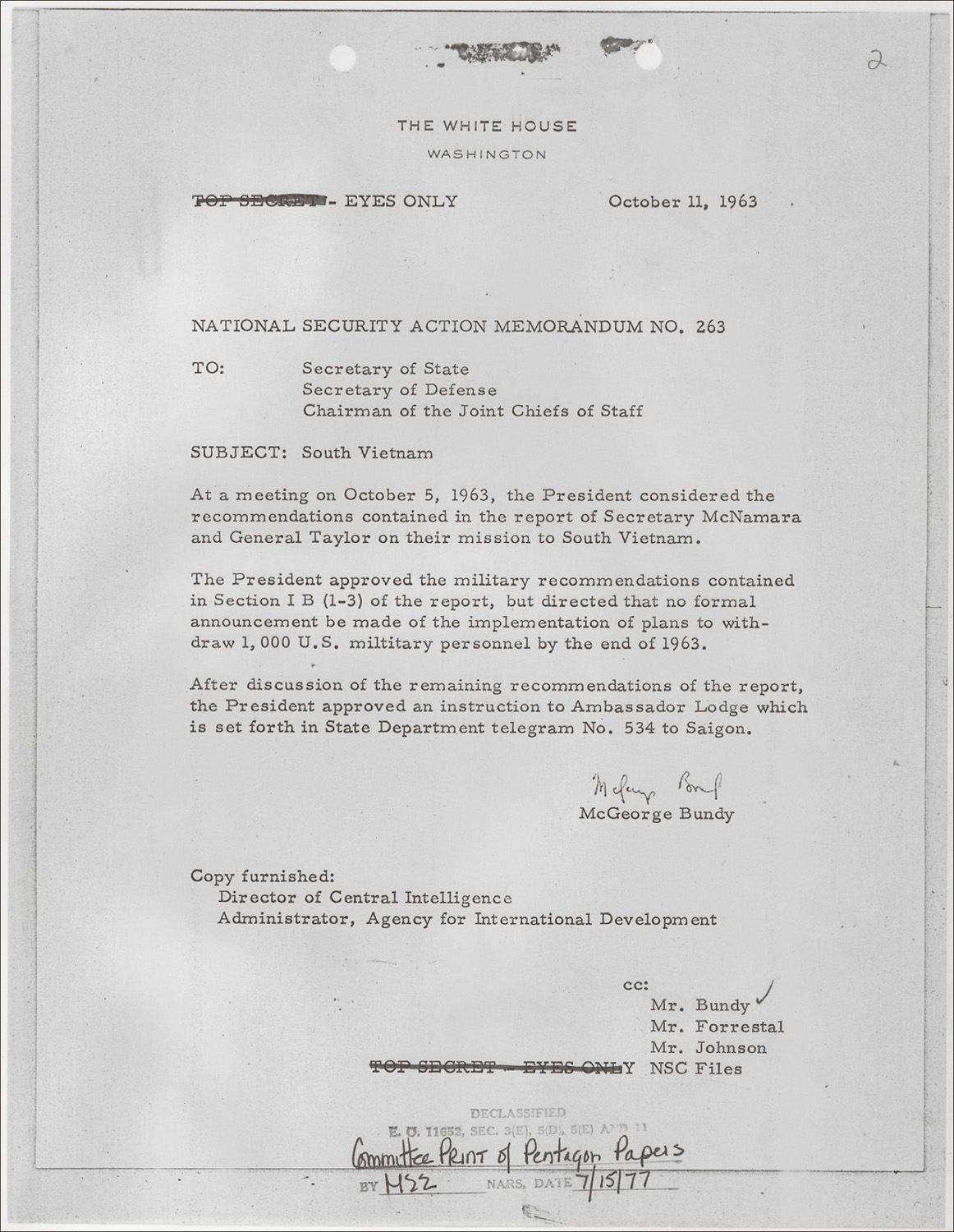

• Just a few months later, on October 11, 1963, roughly six weeks prior to the events at Dealey Plaza, the president secretly issued NSAM 263, stating that a phased withdrawal of all United States troops was to begin with one thousand troops exiting Vietnam by the end of 1963. This decision was based on a report submitted to him on October 2 by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor, also specifying that all troops be withdrawn by the end of 1965.

On November 12, just ten days before his assassination, President Kennedy publicly stated at a press conference that our goals regarding South Vietnam were to bring Americans home, and to intensify the struggle. Nowhere in those remarks was one mention of victory, a turnaround from prior remarks on the subject.

Two days prior to Dealey Plaza, senior Cabinet members and military officials met in Honolulu and issued OPLAN 34A, intended for presentation to the president, which called for intensified sabotage raids against the North utilizing Vietnamese commandos under US supervision. Quite significantly, these plans were not shown to Defense Secretary McNamara, and Kennedy’s withdrawal order was being sabotaged by plans to ship out soldiers who were due for rotation out of Vietnam anyway, rather than withdrawing full units. This was planned escalation by administration officials and the US military, in direct conflict with JFK’s NSAM 263, two days before a new president would be sworn in.123

• JFK was secretly negotiating with Fidel Castro to bring peace between the two countries. Lisa Howard, actress turned news-woman, was the anchor for ABC’s The News Hour with Lisa Howard. Upon her return from interviewing Castro in Cuba in April 1963, Howard reported back to Deputy CIA Director Richard Helms that Castro wanted to talk peace. Helms sent a memo to Kennedy saying, “Castro is ready to discuss rapprochement, and she [Howard] herself is ready to discuss it with him if asked to do so by the US Government.”124

CIA Director John McCone must have been totally opposed to this, and Arthur Schlesinger explained why in 1976: “The CIA was reviving the [Castro] assassination plots at the very time President Kennedy was considering the possibility of normalization of relations with Cuba—an extraordinary action. If it was not total incompetence—which in the case of the CIA cannot be excluded—it was a studied attempt to subvert national policy.”125

Howard bypassed the CIA, and wrote in the War and Peace Report journal that Castro really wanted to begin negotiations with the United States: “In our conversations he made it quite clear that he was ready to discuss: the Soviet personnel and military hardware on Cuban soil; compensation for expropriated American lands and investments; the question of Cuba as a base for Communist subversion throughout the Hemisphere.” After much talk on both sides (Castro even offered to send a plane to Mexico to pick up a Kennedy representative to iron out last-minute details), eight days prior to the assassination, Howard sent a message to her Cuban contact that the president wished to talk.

National Security Action Memorandum No. 263. Unknown or not provided Author, National Archives and Records Administration, October 11, 1962.

On November 18, now three days prior to his death, JFK sent a coded message to Castro in a speech he delivered in Miami at the Inter-American Press Association: “They have made Cuba a victim of foreign imperialism, an instrument of the policy of others, a weapon in an effort dictated by external powers to subvert the other American Republics. This, and this alone, divides us. As long as this is true, nothing is possible. Without it, everything is possible.”126

French journalist Jean Daniel, delivering a message from Kennedy, was with Castro when the news of the assassination came in. Daniel reported that Castro said, “That’s the end of your peace mission. Everything is changed.” President Johnson was told in December 1963 of the proposed peace talks with Castro. He refused to continue the talks. Howard continued her attempts, however, and as a result, she was fired by ABC, because she had “chosen to participate publicly in partisan political activity contrary to long-established ABC news policy.”127

Operation Northwoods: As previously discussed, the Joint Chiefs, presumably in conjunction with the CIA and definitely in conjunction with the State Department, were prepared to fabricate a false flag military attack on the United States in order to provoke war with Cuba, and potentially the Russians. Could they really wait for JFK to complete his almost certain eight years in office?

John F. Kennedy was the first US president since Abraham Lincoln to alienate the office from the forces of the military, big business, and the money powers. He was becoming almost totally autonomous, utilizing the presidency for what he felt was for the betterment of the country. Détente with the Soviet Union and Cuba would have proven disastrous to the military-industrial complex, especially when it came time to escalate hostilities in Vietnam. A limited nuclear disarmament pact with the Soviet Union would have made the domino theory of communist containment a lot less likely for the American public to swallow, meaning potentially billions less in military spending and profits in the decades to come, and far less control for the military. These same forces must have been horrified at the prospect of a friendly Communist Cuba, especially the president negotiating peace with a leader they were trying to kill.

A coup was the only alternative. With either Vice President Lyndon Johnson’s direct participation or his coercion into cooperating, the government of the United States of America changed hands immediately, with LBJ sworn in as president aboard Air Force One. Almost as soon as Johnson deplaned and entered the White House, America’s war activity in Vietnam increased, and détente with Cuba and the Soviet Union ceased to exist. A perfect plot—involve a Communist-leaning and pro-Cuba activist Lee Harvey Oswald, place him six stories above an open presidential motorcade with a high-powered rifle (with additional firepower assistance or not), and swear in a puppet president to execute a 180-degree turn in Kennedy’s American foreign policy.

They had destined Vietnam as the next Korean war machine, a war to test their various new weapons. They would pour the country’s money into it in order to drive up the national debt and their profit, issue the huge contracts for the necessary war materials, and encroach their military bases and warplanes even further into Asia with almost total control over the Southeast portion of the continent. The wealth and strategic power would have been staggering.

President Kennedy, though, had issued orders for all American troops to be withdrawn by 1965, the year he would have almost definitely begun his second term. President Reagan is revered for his part in ending the Cold War; JFK had plans to end it more than two decades earlier and would most likely have done so if it weren’t for a successful coup. Four days after his assassination, and one day after his funeral, President Lyndon Baines Johnson issued NSAM 273, approving intensified covert actions against the North Vietnamese, a preliminary draft (OPLAN 34A) of which was drawn up just two days prior to Dealey Plaza in Honolulu, Hawaii. Paragraph Seven states: “Planning should include different levels of possible increased activity, and in each instance there be estimates such factors as: A. Resulting damage to North Vietnam; B. The plausibility denial; C. Vietnamese retaliation; D. Other international reaction. Plans submitted promptly for approval by authority.”

Retired US Army Major John M. Newman was an intelligence officer stationed at Fort Meade, the headquarters of the National Security Agency. James K. Galbraith discussed Newman’s book JFK and Vietnam in the Boston Review and concluded, “John F. Kennedy had formally decided to withdraw from Vietnam, whether we were winning or not. Robert McNamara, who did not believe we were winning, supported this decision. The first stage of withdrawal had been ordered. The final date, two years later, had been specified. These decisions were taken, and even placed, in an oblique and carefully limited way, before the public.”128

The point, though, is really not if JFK would have withdrawn from Vietnam completely by 1965 or would have reached détente with Russia and Cuba—significantly reducing the perception of a Red Menace—it is that the United States government, from Vice President Johnson, to the CIA and FBI, to the Cabinet, to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the NSA, and all of his advisers believed that President Kennedy was heading in those directions. Short of praying for a loss at the polls in the 1964 election, their only course of action and a deterrent was a coup.

A little more than a year before his death, JFK was discussing the film Seven Days in May with some friends and commented, “It’s possible. We could have a military takeover in this country, but the conditions would have to be just right. If, for example, we had a young president, and he had a Bay of Pigs, there would be a certain uneasiness.”129

Just one week after the assassination, as reported by historians Timothy Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko from declassified Soviet documents, William Walton delivered a message to Khrushchev from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy which claimed that “domestic hard-liners, rather than foreign agents, were responsible” for JFK’s murder.130

According to journalist Bill Moyers, then special assistant to President Johnson, LBJ stated on November 24, 1963, one day before JFK was buried, “They’ll think with Kennedy dead we’ve lost heart. . . . They’ll think we’re yellow and we don’t mean what we say. . . . The Chinese. The fellas in the Kremlin. They’ll be taking the measure of us. They’ll be wondering just how far they can go. . . . I’m going to give those fellas out there the money they want. This crowd today says a hundred or so million will make the difference. . . . I told them they got it—more if they need it. I told them I’m not going to let Vietnam go the way of China. . . .”131 LBJ had just met with, among others, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, George Ball, McGeorge Bundy, Ambassador to South Vietnam Henry Cabot Lodge, and CIA Director McCone. Two days later, Johnson signed NSAM 273.

The CIA and the Pentagon openly preached for war with North Vietnam, the overthrow of Castro, and a build-up of our military and nuclear arsenal. With the exception of a few loners, President Kennedy was proceeding on a collision course with almost the entire Washington establishment. From the June 10, 1963, commencement speech at American University, to NSAM 263, to his potentially favorable conversations with Castro, JFK’s “treasonous actions” had to be silenced, eradicated, and his policies reversed. A simple assassination would have been completely ineffective if LBJ had not cooperated; and by his actions concerning Vietnam, Cuba, and the Soviets, he certainly did from the moment he took the oath of office. Could the mafia have gotten to LBJ? Castro? The Russians? Could any of them have delivered the president to Oswald and/or other gunmen on the grassy knoll in an open motorcade? Only the CIA, FBI, Secret Service, and/or the Pentagon had the power, and the immediate need, to pull it off.

Kennedy was after peace. It would become his legacy. But the real power in the country lay in the military and the CIA, and they effectively totally changed American history in the latter part of the twentieth century. As Peter Janney writes in Mary’s Mosaic:

They had killed Jack because he and his ally-in-peace Nikita Khrushchev were steering the world away from the Cold War toward peace, thereby eliminating the military-industrial-intelligence complex’s most treasured weapons—the fear of war, the fear of “Communist takeover,” and the manipulative use of Fear itself. The Cold War was about to end, and with it the covert action arm of the Central Intelligence Agency. The Agency would have been all but neutered, its funding and resources cut, its menacing grip on public opinion exposed and eliminated. It also meant the eventual curtailment of many of the defense industries, including the proliferation of nuclear arms. There would have been no war in Southeast Asia or Vietnam; that, too, was about to end. A rapprochement with Fidel Castro and Cuba was on the horizon. Both Jack and Fidel wanted “a lasting peace.”

Simply put, peace—particularly world peace—wasn’t good for business, nor for American military and economic hegemony. Whatever enlightenment Mary and Jack may have finally engendered together, it had evolved into a part of Jack’s newfound trajectory of where he wanted to take not only his presidency in 1963, but the entire world. It was the pursuit of peace that was about to take center stage. . . .132

One day prior to Dealey Square, JFK read the latest Vietnam casualty report stating that 100 Americans had died so far and commented to his Assistant Press Secretary Malcolm Kilduff: “It’s time for us to get out. . . . After I come back from Texas, that’s going to change. There’s no reason for us to lose another man over there. Vietnam is not worth another American life.”133 Within twelve years of the illegal seizure of the United States government on November 22, 1963, 58,120 more US servicemen and women perished, 304,000 were wounded, and millions of Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians were killed, wounded, and displaced from their homes.