1 History and Context

In May 1994 the first full Internet operation under TCP/IP protocol in China was established through a direct connection to the American telecommunication company Sprint.1 Also that year, the first web server and the first set of web pages in China were launched at the Institute of High Energy Physics, one of the research institutions under the Chinese Academy of Sciences.2 The number of Internet users in China grew from 620,000 in 1997 to 8.9 million in 2000.3

Fast-forward to 2018. On November 11, 2018, Alibaba, China’s largest e-commerce company, kicked off Singles Day shopping festival, a Chinese version of the American black Friday, with a four-hour gala. “Double 11”—a play on how the number 1 represents being single and unmarried—was reinvented by Alibaba as a shopping event for young consumers. The event in past years has featured many international stars, such as Kevin Spacey, Adam Lambert, Daniel Craig, Miranda Kerr, and numerous Chinese celebrities. Throughout the performances, promotional activities—drawings for free items and gift money, and discounts on various products—were used to stimulate the audience’s purchasing desire. The gross merchandise value of the 2018 shopping day hit a record high of $30.8 billion in sales.4

In a little over two decades, the Internet in China has become a gigantic platform for communication, mobilization, and commercialization. Tracing China’s Internet from its birth through its major stages of growth will help to understand how.

A brief conceptual discussion will be useful. Several scholars have written about the history of China’s ICTs and Internet. Milton Muller, Tan Zixiang, and Wu Wei have discussed the early development of the telecom and data network, with the network building efforts primarily from the Chinese government. Some other scholars have interests in the issue of censorship and control. It is no new argument that China’s Internet was censored by the state and self-censored by the service and content providers.5 Alongside this discussion is a concern for the democratic potential the Internet might bring to China.6 One explanation for the scholarly attention to China’s Internet is that this interest is motivated by the prospect that the Internet could be a democratizing force in a communist regime famously known for censoring media and public opinion.7 The seemingly opposite themes of censorship and democracy actually represent two ends of one central assumption that the Internet is just a tool for enlightenment or suppression. Granting that such argument has some validity, it at its best provides an inaccurate and incomplete account of the digital landscape in China and at its worst invites an oversimplification of the complex social interaction and a neglect of the subjectivities of different agencies and institutions in China. The Internet itself does not stand as an “anonymous, decentralized, borderless and interactive” system for “diverse opinions, civic activities or collective actions.”8 It is the power relation and social dynamic in a system—be it a capitalist or socialist or a mix—that is decisive for the structure of information and communication technology (ICT).

ICT and Internet sectors are not only communication tools or platforms but also integral aspects of the capitalist system. The ICT industry in China has been oriented, in several ways, toward capitalist development, which this chapter examines. It focuses on the historical and regulatory contexts as they not only informed and institutionalized the system of information provision but also reflected the existing power negotiations that have devised the policies. Communication policies respond, to different extents, to some profound questions concerning “the nature of the media system and how it is structured, and how that might affect the conditions for the informational needs of a democracy.”9 More critically, the agendas set by policies are “expressions of dynamic processes and power relations” in a society.10 In China the party-state is one of the most important, though not the only important, powers in setting forward how the emerging communication system is structured.11 Through the prism of policy discourse, we can better understand the political-economic rationales and how relations between different institutions played out in China’s Internet development, laying foundations for private companies like Tencent.

This chapter first traces the history of the building of network infrastructure and services in China, with special attention paid to questions of when and to what extent domestic private capital was allowed into the Internet industry. The Internet in China developed in four distinct stages, and not long after its birth, China’s Internet was embedded in the country’s capitalist development and global reinsertion through industrialization and informatization. Both as an enabling condition and an outcome, priority was given to building the information network and industry in coastal and urban areas, which contributed to not only the creation of an enormous pool of migrant labor but also to the user base for new Internet services and applications. Throughout, the chapter shows that China’s ICT industry and capitalist investments mutually constituted and facilitated each other’s development under the evolving central government policies, and together industry, investment, and government gave birth to Tencent.

Building a Chinese Internet

The Chinese central government’s policies on Internet development and the efforts in building the information superhighway went through four stages: the preparation, 1987 to 1993; the Internet as infrastructure, 1994 and 1995; the Internet as industrialization, 1996 to 2010; and the Internet as a pillar industry, 2011 to the present. Throughout these processes, capital has been visible, but different units of capital—state-owned units and private ones—were allowed to enter the industry to different extents. In the two early stages, the driving force came primarily from state-owned capital backed by the central government’s informatization policies. Private capital and foreign capital were given more space in the latest two stages, which reflected China’s further opening up and integrating into global capitalism. These stages were also parallel to China’s overall political-economic transformation since the 1980s. In 1978 not only had the central government in China decided to liberalize and open up the domestic economy but it also rediscovered the foundational position of science and technology in boosting economic productivity.12 The Internet’s second stage of development came along with China’s then top leader Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour to Shenzhen among other southern coastal cities in 1992, during which he affirmed the opening-up policies to further connect with the worldwide market economy and to use foreign capital to facilitate domestic growth.13 The third stage broadly correlated with an era when China sought to aggressively reintegrate into global capitalism by using ICTs both as a channel for communication and a vehicle for attracting investments, while more recent developments came under the country’s post-crisis rebalancing.

Preparation: 1987–1993

The first stage was the preparation years between 1987 and 1993, during which policies were focused on encouraging scientific research and popularizing networking technology.14 This period was marked by two milestones, with primary efforts from the Chinese government-funded science-and-technology research institutes and universities. The first event, in September 1987, was the first e-mail message—“Across the great wall, we can reach every corner in the world”—sent across China’s borders.15 This message, sent when China was still considered by many as a closed, authoritarian land, signaled that researchers could exchange e-mail communication with foreign educational institutions.16 A second turning point was in 1994 when the first full Internet operation under TCP/IP protocol in China was, for the first time, up and running.17 This meant that China started enjoying “full general Internet connectivity beyond just e-mail” by making a direct connection between China and the United States.18

In this period, the Chinese government gave priority to network development in preparation for the launch and upgrade of national information infrastructure, the work of which was mostly based in research and educational institutions. For example, the academy network of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CASNET) and the campus networks of Tsinghua University (TUNET) and Peking University (PUNET) were all constructed during this time.19 Not much emphasis was put on the economic potential of the Internet during this stage.

The Internet as Infrastructure: 1994 and 1995

The second stage, during 1994 and 1995, saw a wave of construction of the basic network infrastructures by academic institutions, government agencies, and, occasionally, some primary commercial carriers.20 The Internet was primarily seen as a platform and tool for communicating and disseminating information to facilitate industrialization in major agrarian and industrial sectors. By the end of 1995, China had “10 national networks, 41 leading governmental information services in electronic form, 16 news sources in electronic form, 43 university-based World Wide Web servers and information producers, and 52 commercial information products prepared by electronic information producers.”21

One example of such effort was the China Education and Research Network (CERNET), a nationwide backbone network to connect the campus networks of universities and research institutions.22 The State Development Planning Commission, China’s National Science Foundation, and China’s State Education Commission initiated and funded the project, which was officially approved in August 1994.23 CERNET’s demonstration project, completed by the end of 1995, made it the leading network in China in terms of backbone speed and range of coverage, reaching more than a hundred universities in China and covering all mainland provinces except Tibet.24 CERNET also provided an international connection to global academic networks through a 128K international special line to the U.S. Internet.25

Another nationwide backbone network was ChinaNET, led by the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (MPT) and carried out by its Directorate General of Telecommunications, an office in charge of providing national telecommunications services.26 ChinaNET offered international links in three major cities—Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou—by working with Sprint.27 Spearheading China’s information-highway project and prioritizing service provision to the three largest cities at the time, MPT became the leader in providing commercial Internet services.28 By 1995 ChinaNET was the largest commercial Internet service provider in China.29

Although the commercial value of the Internet was starting to get some attention, the priority of central government in this period was to facilitate public information exchange and support macro level economic planning and administration via an effective and reliable information infrastructure.30 In March 1993 vice premier Zhu Rongji initiated the Golden Bridge Project, a national network for public economic information; in August the State Council of the People’s Republic of China approved a $3 million budget to build it; and in June 1994 the State Council issued a notice to expand the Golden Bridge Project into three golden projects.31 The additional two projects were the Golden Gateway, a central information system of foreign trade and import-export management, and the Golden Card, a central financing, banking, and credit card system.32 As these three projects were effective in providing key information and assisting the central government’s economic planning, coordinating, and managing, in 1995 more golden projects for various industries were brought into being—Golden Tax, Golden Enterprise, and Golden Agriculture, among others.33 Serving primarily as communication channels of information for policymaking in different industries, these networks strengthened the central government’s coordinating power.34

The Internet as Industrialization: 1996–2010

The 15 years between 1996 and 2010 constituted a third stage during which the Internet and information industries were intensively developed as vehicles for economic growth. In the prior stage, information technology was used in selected primary and secondary industries for their growth. In this third stage, instead of being merely a tool, ICTs became important in their own right for the country’s industrialization. This stage pivoted on a set of distinctive changes in industrial structure and government structure.

First, on the industrial landscape, in January 1996, during its 42nd meeting, the State Council approved a provisional directive on the management of international Internet connections in China, which endorsed the MPT as the official leader in the country’s Internet business: “All international computer networking traffic, both incoming and outgoing, must go through telecommunication channels provided by the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications.”35 MPT’s Directorate General of Telecommunications was renamed China Telecom and restructured as a state-owned enterprise under China’s 1995 telecom reform. This was the first time the Chinese government regulated the use of the Internet, an indication of its growing importance.36 According to the directive, the government was in charge of the planning work and protocols for all international computer connections. All existing networks were subject to MPT supervision and that of the Ministry of Electronics Industry (MEI), the State Education Commission, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences for the management of general Internet traffic, computer companies, and education and research institutions, respectively.37 The country was making necessary preparations for advancing technology in the national economy. The regulation also highlighted that all the international information traffic—both incoming and outgoing—had to go through MPT’s telecom network and under the government’s scrutiny.38 This showed that the Chinese state was open in embracing foreign flows of information and, simultaneously, cautious in encountering potentially different and antagonistic thoughts and ideologies, as this was at a time when the overall national economy was transforming into an outward- and export-oriented mode, and the international flows of information and capital were becoming both necessary and preferable.39

Following this provision, in March 1996 the National People’s Congress approved the Outline of the Ninth Five-Year Plan (1996–2000) for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives to the Year 2010 (hereafter referred to as the Outline), in which the phrase “information technology and informatization for economic development” for the first time appeared, and the growth of computer and Internet technology was an integral goal for the next five years’ economic and social development.40 The Five-Year Plans, to be sure, were a series of social and economic development initiatives designed by the central Chinese government, the first of which began in 1953. It was in this very Outline that the government proposed that a socialist market economy was to take shape initially in the five-year frame of 1996 to 2000: “Positive but cautious steps must be taken to foster a comparatively perfect money market as well as markets in such key areas as real estate, labor, technology and information.”41 Specifically, technology and information were utilized to achieve readjustment of the industrial structure from an extensive mode—one that emphasized “aggrandizement of the total size”—to an intensive one that highlighted “the efficiency in utilizing each unit of input in production or allocation.”42 Furthermore, the Outline discussed the role of various economic elements and capital units from different sectors, as well as the investment system and fund-raising scheme in the market.43 In particular, it articulated that the nonpublic elements, that is, individuals and private actors, should be strengthened to supplement the public ownership-dominated economy system.44 This meant that further reform was to take place, where private units were allowed gradually to participate in the national economy. It was under such context that China’s Internet industry blossomed. In other words, the development of information technology and Internet came under the central government’s umbrella agenda of deepening the country’s market economy reform and opening-up process.45

Echoing the Outline, the State Council’s Information Work Leading Group held its first national meeting on the issue of informatization in 1997 and announced the Ninth Five-Year Plan for Informatization and Long-Range Objectives to the Year 2010. The Plan specifically called for “joint efforts” by the state and other economic elements to build the Internet and information sectors.46

The five-year period of the Ninth Five-Year Plan saw a great amount of government funding in information infrastructure and technological innovation. A $12.24 billion (RMB 101.5 billion) investment was put into building special zones for high-tech development, where 17,000 high-tech enterprises were in operation and more than 2.2 million people were employed between 1996 and 2000. Another $385 million (RMB 3.19 billion) was used for “technical innovation projects in the industrial sector.”47 As a result, the national economy output and especially that of information industries witnessed huge surges. The gross output value of electronic information products manufacture (software manufacture included) increased from $29.43 billion (RMB 245.7 billion) in 1995 to $93.87 billion (RMB 778.2 billion) in 1999, while the gross value of general communication services grew from $11.84 billion (RMB 98.9 billion) in 1995 to $25.49 billion (RMB 211.3 billion) in 1999.48 According to a China Daily report, those 17,000 high-tech enterprises in special high-tech development zones contributed an industrial added value of $17.8 billion (RMB 147.6 billion) and an export trading volume of $12 billion.49

A second change in this period was the administrative reform and restructuring of central government agencies that regulated the management and businesses of the Internet. As early as December 1993, the central government named an interdepartmental task force for joint leadership on issues of “informatization for economic development,” chaired by then vice premier Zou Jiahua.50 This task force of the State Economic Informatization Joint Meeting was renamed the Information Work Leading Group and under the State Council. With Zou still acting as the head of the office, the Information Work Leading Group was coordinated by staff members from 19 ministerial departments, commissions, and bureaus.51 In 1999 the State Council set up a National Information Work Leading Group, chaired by then vice premier Wu Bangguo with staff members from 13 ministerial departments, commissions, and bureaus.52 The added term “national” suggests the importance the central government attached to information for industrialization. Premiers Zhu Rongji and Wen Jiabao subsequently took charge of this leading group. The National Information Work Leading Group was closed in 2008, when the “superministry reform” took place, and was merged into the newly established Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) as part of its information technology promotion division. In 2014, however, the central government, under the leadership of president Xi Jinping, founded a new office—the Central Leading Group for Cyberspace Affairs and the Cyberspace Administration of China—to enhance China’s Internet security and strengthen the informatization strategy.53 The Central Leading Group for Cyberspace Affairs has carried forward the heritage from State Council’s previous joint task forces and also aimed to respond to the opportunities and challenges in the new era, since paramount importance was put on Internet and ICTs as the new pillar industry for national economy.54

Another aspect of this governmental restructuring involved changes to ministries that regulated the Internet and information industry. Historically, MPT operated and managed the information and communication services.55 Although central government agencies had always fought for control over this lucrative sector, the rivalry became especially intense when the MEI set foot in telecommunication services by launching China United Telecommunications Corp. (China Unicom) in 1993 jointly with two other ministries—Ministry of Railway and Ministry of Electronic Power.56 MEI later formed another telecom company, Ji Tong, which built on the ministry’s strength in equipment manufacturing.57 In view of an increasing overlap and interconnection between electronics and the information industries, the central government reorganized MPT and MEI and formed one ministry, the Ministry of Information Industry (MII) in 1998.58 This reorganization, aiming at facilitating economic transitions and enhancing administrative efficiency, spoke to the centerpiece of the state’s policies at this time—the Internet and information for industrialization.59 In 2008 the ministerial reform continued, and the newly formed MIIT incorporated the functions of several central agencies: MII; National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC); the Commission of Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense, except their oversight of nuclear power management; and the State Council’s Informatization Office.60 In addition to the changes in the ministry titles, the reconstitution of the MIIT as a more comprehensive entity reflected a further integration of informatization and industrialization.61

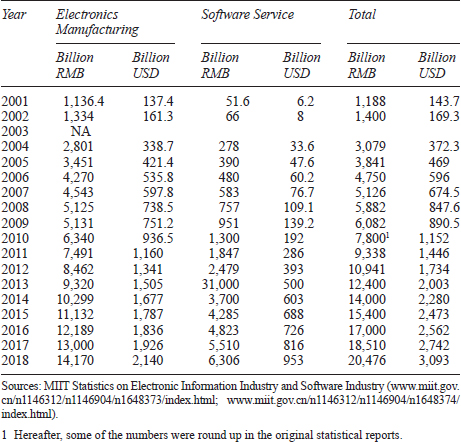

As a result of these changes in the industrial and governmental dimensions and the progress made during the Ninth Five-Year Plan period, the Tenth and Eleventh Five-Year Plans kept readjusting industrial structure and assigning more weight to the Internet and ICTs. Growth was little short of explosive. By the end of 2005, the total gross income of the information industry reached $537 billion (RMB 4.4 trillion)—4.6 times the figure in 2000—and the industry’s added value in national GDP increased from 4 percent in 2000 to 7.2 percent.62 Between 2006 and 2010, a total of $188 billion (RMB 1.5 trillion) was put in the telecommunication industry, with 40 percent of investment for broadband construction.63 By the end of 2010, the sales of the information industry topped $1.15 trillion (RMB 7.8 trillion).64 ICT and Internet businesses expanded as a driving force for innovation and development in other industries, as well as a core industry themselves.65

|

Year |

Billion RMB |

Billion USD |

|

2000 |

341 |

41.2 |

|

2001 |

415 |

50.1 |

|

2002 |

463 |

56 |

|

2003 |

517 |

62.5 |

|

2004 |

573 |

69.3 |

|

2005 |

637 |

77.8 |

|

2006 |

712 |

89 |

|

2007 |

805 |

105.9 |

|

2008 |

814 |

118 |

|

2009 |

871 |

128 |

|

2010 |

899 |

132.8 |

|

2011 |

1,066 |

165 |

|

2012 |

1,186 |

188 |

|

2013 |

1,169 |

188.9 |

|

2014 |

1,154 |

187.9 |

|

2015 |

1,125 |

181.5 |

|

2016 |

1,189 |

180.2 |

|

2017 |

1,262 |

185.6 |

|

2018 |

1,301 |

194.36 |

Source: MIIT Annual Statistics on Telecommunications (www.miit.gov.cn/n1146312/n1146904/n1648372/index.html).

Table 1.2 Annual Sales Income in Chinese Electronic Information Industry

The Internet as a Pillar Industry: 2011–present

A fourth turning point took place in the wake of 2007–8 financial crisis, when the Internet industry was given added weight by the state. This is a still-ongoing process in which the Internet industry itself has become the backbone of the economy.

Since China’s 1978 opening-up and market reforms, the country’s spectacular economic growth largely has depended on foreign direct investment and trade export.66 The achievements are stunning. By 2010, China was the world’s largest exporter of goods, contributing to 26.53 percent of the country’s GDP and accounting for 9.6 percent of all global exports and, especially, the world’s largest exporter of consumer electronic products.67 However, as many have noted, “in the complex global supply lines of multinational corporations, China primarily occupies the role of final assembler of manufactured goods to be sold in the rich economies.”68 Despite its leadership in bulk, there was an Achilles’s heel in such an outward- oriented economic mode—high dependence on the global supply chain. Famously known as a “world factory,” China did not possess the core competitiveness for a domestically strong and innovative ICT industry.69 Moreover, the fast growth rate in GDP from this foreign investment-driven and export-oriented growth model was accompanied by a series of social problems crystallizing on social inequalities, regional imbalances, massive unemployment, and environmental problems.70 All these problems, aggravated by the 2007–8 global financial crisis, acted as a wake-up call to the Chinese state that its economic advancement held multifaceted consequences and needed to be revised.

In this context, at the 2011 National People’s Congress meeting, the central government designated the Internet and ICT sector as the pillar industry in national economic restructuring.71 The Twelfth Five-Year Plan, approved in that meeting, highlighted that to boost domestic consumption by capitalizing on the Internet was a priority. One of the core messages in the Twelfth Five-Year Plan was to cultivate and promote strategic industries of ICTs for a “modern production structure.”72 This signaled a further integration of private businesses with ICTs and an ever-interweaving relation between the state and different units of capital. During the Twelfth Five-Year Plan period, from 2011 to 2015, improved Internet infrastructures and widening diffusion of the mobile Internet brought forward a prosperous Internet economy. In 2014 Internet businesses alone accounted for 7 percent of national GDP, while the market value of Internet companies amounted to $1.24 trillion (RMB 7.85 trillion) and occupied 25.6 percent of China’s stock market.73 As of 2015, 328 China-based Internet companies were publicly listed, with 61 in the United States, 55 in Hong Kong, and 209 in China in Shanghai and Shenzhen.74 E-commerce, in particular, became a new driving force for trade and consumption. In 2017 the income of e-commerce platforms was $32.23 billion (RMB 218.8 billion) with “a year-on-year increase of 43.4%,” and online retail transactions were worth $1.06 trillion (RMB 7.18 trillion).75

In the midst of restructuring, the latest policy discourse of Internet Plus further upgraded this pillar industry. The term Internet Plus refers to the state’s plan to build a network of banks, financial services, e-commerce, entertainment, and other daily services around the Internet-based technologies, including using mobile Internet, cloud computing, and big-data techniques.76

The concept was first reported in premier Li Keqiang’s 2015 Report on the Work of the Government. Reflecting the desire for a dynamic and expansive Internet industry, the policy was matched by top leaders’ high-profile visits to the Internet companies, “Taobao villages,” and high-tech start-up firms created since Xi Jinping’s and Li’s Keqiang’s inaugurations. With an overarching agenda to restructure the general national political economy around the Internet, the purpose of Chinese central government also went beyond economic.77 In July 2015 the State Council issued Instruction on Actively Promoting Internet Plus Strategy, which promotes using Internet as a stage to advance public services, with a goal to integrate every aspect of society into a networked China by 2018.78

To recap, China’s Internet experienced four stages of development: the years between 1987 and 1993 were the preparation stage, when multiple research teams under government funding were exploring ways of building a domestic network and connecting to the world. During 1994 and 1995 massive network infrastructure construction was underway as the Internet was primarily seen as a platform where information can be collected and distributed to facilitate central planning and agrarian and industrial development. From 1996 to 2010, as China was reinserting itself into transnational capitalism, the domestic Internet industry evolved as an important vector that generated extraordinary GDP growth. The latest stage elevated the Internet to the pillar industry as the core of the national political economy in the wake of the 2007–8 global financial crisis. Overall, grasping the worldwide moment of the “modernization and globalization of communication networks and the rapid diffusion of powerful information technology,” the Chinese government designed policies that gradually integrated the Internet into the national political economy.79

Prioritizing Capitalist Pursuit and Urban Development

To facilitate the changing industrial structure, an important shift in policies regarding private capital has taken place since the 1990s.80 That was to unleash nonstate elements into building information and Internet infrastructures. With the opening of domestic stock markets in Shanghai and Shenzhen in 1991 and 1992, private and, particularly, financial capital became major players in China’s economy. As a crucial reminder, there have been some ambiguities and contentions in the definition of private ownership. While the Chinese government defined a private company as “a for-profit organization owned by one or more individuals and employing more than eight people,” as Edward Tse points out, this definition excludes a number of business governance structures (such as companies with less than eight employees) or collectively owned businesses (such as Haier and Huawei) or foreign private capital-invested enterprises (such as Alibaba and Tencent).81 For simplicity and clarity, in the following analysis, private capital is referred to generally as non-state-owned companies that Chinese individuals initially formed and operated. The statistics that follow also refer to private enterprises as “enterprises established by a natural person or majority owned by a natural person” in China.82

Despite that the blurry definition and variations in practices made a precise measurement of its size difficult, some general numbers reveal the advance of China’s private capital.83 According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, in 1996 there were 443,000 registered private companies, which accounted for less than 20 percent of all enterprises; in 2012 the number of private companies reached 5.918 million, which accounted for more than 70 percent of all firms.84 The private companies’ shares in China’s export increased from almost 0 in 1996 to 39 percent in 2013.85 Under the central government’s guidance to allow various business elements into the national economy, private capital has flourished and changed the industrial dynamics.86

Particularly in the Internet industry, value-added service (VAS) providers and content providers started to emerge. Almost no official record exists on the exact number, size, and scale of private companies established at that time. While it is difficult to present a comprehensive evaluation, some anecdotal writings allow a glimpse of the “Internet gold rush.” In 1995 Chinapage—an online yellow-page listing of Chinese businesses and products and founded by Jack Ma, AsiaInfo’s ChinaNet, Zhong Wang, and Ying HaiWei—came into being.87 Between 1996 and 2000, many companies that became better-known in the future were founded. In 1996 Charles Zhang established Sohu.com; in 1997 William Lei Ding launched NetEase, offering one of China’s earliest free e-mail services; 1998 and 1999 subsequently saw the births of Sina, Tencent, Sohu, NetEase, Jingdong, Ctrip, Baidu, and Alibaba—to name a few.88 Some of these became extraordinarily successful, and issuing an initial public offering (IPO) on overseas stock exchange markets became a popular option for them. The processes generated complex and often profitable financial structures. As of 2018, seven of them—Tencent, Sohu, NetEase, Jingdong, Ctrip, Baidu, and Alibaba— remain among China’s top ten Internet companies.89 The emergence of these Chinese Internet companies was almost at the same time as the Internet boom in the United States.

|

Company |

Year Founded |

Year of IPO |

Listing |

Business |

|

Sohu |

1996 |

2000 |

NASDAQ |

Online portal |

|

NetEase |

1997 |

2000 |

NASDAQ |

Online community |

|

Sina |

1998 |

2000 |

NASDAQ |

Online media |

|

ChinaCache |

1998 |

2010 |

NASDAQ |

Content delivery |

|

JD.com (Jingdong) |

1998 |

2014 |

NASDAQ |

E-commerce |

|

Tencent |

1998 |

2004 |

HKEX |

Value-added service |

|

Ctrip |

1999 |

2003 |

NASDAQ |

Online travel agency |

|

1999 |

2010 |

NYSE |

Online real-estate |

|

|

Alibaba |

1999 |

2014 |

NYSE |

E-commerce |

|

Baidu |

2000 |

2005 |

NASDAQ |

Search |

|

Bitauto |

2000 |

2010 |

NYSE |

Online automobile |

Sources: NASDAQ and NYSE company lists.

With the massive flow of foreign and domestic investments, at the same time, there came the changing landscapes of urban/rural dynamics and population structures, as both a precursor and result of the political-economic shifts that gave rise to China’s Internet industry. Specifically, two major shifts took place: the formation of special economic zones (SEZ) and the growing urban, middle, and working classes, who composed a majority of the workforce for and users of ICTs.

Special Economic Zones

During the early years of China’s reform, the Chinese government designated two coastal provinces—Guangdong and Fujian—to be the frontrunners in attracting foreign investment, developing industrial clusters, and enjoying favorable policies.90 In 1980 four cities in these two provinces—Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen—were designated as special economic zones (SEZs).91 According to the Regulation on Special Economic Zones in Guangdong Province,

Immediate economic effects were documented in just the first few years of the openings of SEZs. In 1981 the four SEZs attracted 59.8 percent of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) to China, with Shenzhen alone accounting for 50.6 percent.93 In 1984 after China started opening more coastal regions for special economic treatment, these four SEZs still accounted for 26 percent of the nation’s FDI, totaling $707.58 million.94 Witnessing the momentous growth of SEZs, the central government started establishing economic and technological development zones (ETDZs). Between 1984 and 1988, 14 ETDZs were launched, including Dalian, Qinhuangdao, Tianjin, Yantai, Qingdao, Lianyungang, Nantong, Minhang, Hongqiao, Caohejing, Ningbo, Fuzhou, Guangzhou, and Zhanjiang.95 While these ETDZs tended to be relatively smaller suburban areas than SEZs, they also enjoyed preferential tax treatment in order to enhance investment environment and encourage industrial projects in the high-tech industry.96 Two more waves of substantial growth in ETDZs took place around 1991 to 1992 and 2000 to 2002. In 2003 the realized inward FDI in these zones amounted to $15.769 billion.97 As of 2016, 54 state-level ETDZs existed in China, with 32 in coastal regions and 22 in the hinterland.98

To level up the productivity of the SEZs and ETDZs, ICT infrastructure building became a priority. In pursuit of capital formation and network upgrades, China’s government was first and foremost concerned with “linking coastal cities and responding to the demand of businesses” for the outward-looking economy, and, according to Yu Hong, the telecom infrastructure and communication facilities in Guangdong were much better versed than the inland provinces like Hunan and Sichuan.99

These elements advanced the social-economic conditions in coastal areas that gave birth to numerous technology companies. Taking Shenzhen as an example, the share of high-tech industries in its total industrial output increased from less than 10 percent in 1990 to nearly 40 percent in 1998.100 Some saw Shenzhen city as China’s Silicon Valley: in 2014 alone Shenzhen hosted a total of $10.42 billion (RMB 64 billion) in investment in research and development (R&D).101 Apart from foreign-funded or established technology companies, some well-known domestically launched firms grew here, including the global telecommunications equipment leaders ZTE, founded in 1985; Huawei, founded in 1987; and the Internet giant Tencent.

The Workforce

A second aspect of the massive industrialization and urbanization was the rise of an urban working class, as “the growing ICT sector has become a major destination for millions of peasants-cum-workers.”102 According to MII’s documentation, about 6.2 million people were working in the electronic information industry in 2002, up from 1.5 million five years before; 16 million workers (6.7 percent of the urban employment) were employed in the broadly defined ICT industry.103

In a more general sense, an even larger population formed what Jack Linchuan Qiu called the “information-have-less”: 247 million migrant workers as of 2015, 114 million manufacturing workers as of 2013, 227 million people under four years of age and 222 million people 60 years old and older.104 These people were the primary users of less expensive, more accessible, and low-end ICTs, such as “second-hand phones, used computers, pirated DVDs, Internet cafes, short-message service (SMS), prepaid mobile service, and the Little Smart low-end wireless phone.”105 These populations would become active users of many of Tencent’s popular products, such as QQ, WeChat, and mini-games, among others, discussed in later chapters.

The Birth of Tencent

Founded in 1998, Tencent started the business with an instant messaging (IM) service—QQ. QQ, developed by Tencent’s five core founders—Ma Huateng, Zeng Liqing, Zhang Zhidon, Chen Yidan, and Xu Chenye—was a localized adaptation of ICQ, an instant messenger an Israeli company originally invented.106 Tencent has been working continually on adding Chinese features to this instant messenger system ever since. The wide popularity of QQ won Tencent a large user base in China. By the end of 2018, QQ’s monthly active users (MAU) reached 807 million.107 Thanks partly to such a gigantic user base, as will be shown, Tencent’s businesses have expanded to a variety of other value-added Internet, mobile, and telecom services. Value-added services (VAS) are generally defined as “enhanced data- processing services” beyond the basic voice services ordinarily provided by telecommunications carriers.108 In China, the State Council promulgated the Telecommunications Regulations of the People’s Republic of China first in 2000 in which the differences between the basic and the VAS were specified:

In the case of Tencent, its VASs include entertainment, social networking, communication and information portal, gaming, and e-commerce, among others, on smart mobile handsets and the home devices.110 In June 2004 Tencent launched an initial public offering (IPO) of shares on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. At the end of 2018, its revenue topped $45.56 billion (RMB 312.69 billion).111 The company, identifying itself as an “online lifestyle services provider,” claims to be “China’s largest and most used Internet service portal.”112 Tencent is currently among the top ten largest Internet conglomerates worldwide in terms of market value.113

Tencent was founded at a critical point to both Chinese and global Internet industries. On the domestic side, Deng embarked on his second southern tour in 1992 during which he firmly advocated further reform and more economic liberalization.114 This speech carried far-reaching historical significance for China’s economic development, as Deng’s famous statement, “Be it a black cat or a white cat, a cat that can catch mice is a good cat,” was generally recognized as an open and welcoming attitude to the capitalist market.115 Shenzhen, where Tencent’s headquarters is based, greatly benefited from Deng’s visit and became one of China’s earliest SEZs that opened up to foreign capital after 1992.116 In just one year after Deng’s visit, the amount of FDI into Shenzhen rose from $250 million in 1992 to $497 million in 1993. In 2009 the amount of FDI in Shenzhen reached $4.2 billion.117 The per capita GDP in Shenzhen increased from $1,825 (RMB 8,720) in 1990 to $8,713 (RMB 69,450) in 2006, and GDP was growing at a rate of 14 to 20 percent a year between 1995 and 2006.118 At the same time, Shenzhen was among the first few cities in China to have Internet access via China Telecom, after the first full Internet operation using the TCP/IP protocol in China was launched in 1994.119 The following years saw Internet companies springing up all over China, particularly in Shenzhen. On the global side, at the same time, ICTs were becoming booming industries for the economy in the United States. Particularly, this was evident in the rise of the NASDAQ, where a growing number of technology companies were publicly listed. Tencent, emerging in the concluding years of the 20th century, is one example of this global Internet gold rush.

Conclusion

This chapter provides a review of the political-economy context within which China’s ICT industry and, more specifically, Tencent grew. As the four stages of major changes in policy guidelines and articulation delineate, these shifts were not incidental. They were both the preconditions and outcomes of the overall political-economic transformation that took place in China’s contemporary history. The evolution of the Internet from a network infrastructure that facilitated industrial development to a central node of national economy itself reflected a broad political-economic transformation from an outward-looking production mode that was heavily dependent on FDIs in manufacturing to a domestically centered and consumption-driven mode with the support from portfolio investments.120

While these changes and developments were highly government initiated, they represented a more general pattern in the world, where private capital—whether domestic or foreign—was unleashed to build a country’s economy. China was the leading example of this pattern. Based on the experience of other countries, China’s leaders sought to gradually open up the domestic market to foreign investors as well as to domestic private companies. At the same time, this process also displayed some Chinese characteristics—the restrictions on FDI in certain areas. A result of the restrictions was an extensive incorporation of foreign venture-capital investments in the Internet industry, which is further discussed in following chapters on Tencent’s capital structure. In other words, Chinese Internet policies had always made room for capital development, yet they were continually adjusted in terms of room for whom and development of which unit of capital—if it was state-owned or private-owned and if it was domestic or foreign.

These changes responded to both internal and external challenges and demonstrated an intertwined relation between the Chinese state and various units of capital. On the domestic side, a growing Internet industry could be attributed to several factors, including the elevation of private capital, the participation of domestic and foreign units of capital, a spatial shift in the allocations of the great labor army, and policy preferences given to the information technology sector. Internationally, foreign investors’ desires to enter the Chinese market, the rise of a global financial sector, the collaboration with the rising power of Silicon Valley, and the crisis and depression of the latest years also contributed to the Internet boom in China at different stages. The negotiations, collaborations, and competitions among different state sectors and units of capital have been ongoing.