4 Cultural Profile

Tencent, as an Internet giant, substantially controls a variety of online value-added services (VAS) in China’s Internet industry, including IM, social networking, online entertainment, gaming, and e-commerce, among others. This chapter turns to the cultural sphere to review Tencent’s popular products and cultural influences and their connection to its transnationalization strategies. After an overview of Tencent’s cultural products, the chapter dives into the two most popular and successful products and services—mobile chat and digital gaming—and discusses how Tencent managed to monetize its mobile chat apps and VAS, including QQ and WeChat, through a bittersweet relation with China’s major telecom carriers. Tencent’s roadmap to becoming a global giant in the game industry used the gaming sector as an entry point to gain transnational competitiveness. Building upon its advantages in numbers of users, capital power, and global reach, Tencent has not only established itself as a vertically integrated global gaming empire—from engine services to game development and to publishing and distribution—but and also formed a cultural synergy of gaming, mobile and online communication, and social networking. The chapter concludes with an evaluation of Tencent’s overall transnationalization strategies in the cultural industries.

Tencent’s Cultural Products

Tencent’s flagship products—QQ, WeChat, and online games—generate the greatest portion of revenues annually. They form a unique cultural brand for the company and a community for its diverse users.

As one of the first free instant messaging (IM) services in China, QQ accumulated registered users very quickly. In May 2000, within only half a year of its debut, OICQ’s online users reached 100,000. “As a domestically developed online paging software, OICQ was the best. It brought us a lot of conveniences and friends,” People’s Daily commented on May 29, 2000.1

|

Year |

Account |

|

|

Registered User (Million) |

Active User (Million) |

|

|

2004 |

369.7 |

134.8 |

|

2005 |

492.6 |

201.9 |

|

2006 |

580.5 |

232.6 |

|

2007 |

741.7 |

300.2 |

|

2008 |

891.9 |

376.6 |

|

2009 |

* |

522.9 |

|

2010 |

647.6 |

|

|

2011 |

721.0 |

|

|

2012 |

798.2 |

|

|

2013 |

808.0 |

|

|

2014 |

815.3 |

|

|

2015 |

853.1 |

|

|

2016 |

868.5 |

|

|

2017 |

783.4 |

|

|

2018 |

807.1 |

|

* Tencent no longer documented this item starting with the 2009 annual report.

Note: Figures are for the last 16 days of the fiscal year, ending December 31.

Sources: Tencent, Annual Reports, 2004–18 (revenue year-end of December 31).

The popularity did not bring much profit for Tencent at the beginning, though. Instead, to maintain the server, Tencent had to throw in a great deal of money, which caused its serious financial difficulties in 1999 and 2000.

It was not until QQ became available on mobile devices that Tencent was able to monetize it. Mobile QQ is similar to QQ in function, as mobile QQ allows users to exchange instant messages through preinstalled QQ software on mobile SIM cards and devices. In order to make this work, Tencent collaborated with telecommunication carriers and device manufacturers. When users chat with friends on their mobile phones via QQ and related services, they bring traffic and, hence, revenues to telecom operators’ networks. A large portion, 63.6 percent, of Tencent’s 2003 revenues in mobile and telecom VAS came from the mobile-data fees that mobile users paid with their subscriptions; the fee was determined by fixed terms with Chinese telecom giants.2 Tencent also worked with mobile device manufacturers to “preload QQ client software on the advanced mobile phones and conduct joint marketing activities to customize the QQ client software for various mobile handset environments.”3

Enterprise IM

In addition to personal services, Tencent also developed IM products for corporate communication. In April 2002, Tencent first launched BQQ, a corporate version of QQ for business communication within an enterprise.4 In August 2003, Tencent upgraded BQQ and launched a new product, Real Time eXchange (RTX).5 In working with individual companies, Tencent helped to build internal communication networks that allowed corporate employees to communicate instantly and locally.6 In the following years, Tencent collaborated with IBM and Cisco in developing RTX, IBM and Cisco providing their expertise in enterprise communication services and software technologies.7 Some important customers included Postal Savings Bank of China, Jiangsu Provincial Taxation Bureau, Air China Limited, the northwestern branch of Sinopec Group, and Chia Tai Group.8

Weixin and WeChat

On January 21, 2011, Tencent released a mobile device-based chatting service, Weixin and WeChat, with Weixin the name for its Chinese services and WeChat the one targeting overseas users.9 The core service is based on instant messaging, but Weixin/WeChat is more than just a chatting tool. It integrates other value-added functions and eventually became a gateway for users to connect online and offline lives and to integrate the two in one app. Upon its launch, Weixin/WeChat gained immediate growth and has quickly become a major communications and social platform for smartphone users in China.10

Other VAS of social networking, entertainment, gaming, e-commerce, group purchases, local business reviews, online payments, and others were constantly added onto the Weixin and WeChat platform, which made it a multifunction hub for online lifestyles. For example, Weixin/WeChat Moments, a feature to share experiences, blogs, photos, and articles through publishing to users’ Weixin/WeChat contacts, became another social platform for user interactions, in addition to Tencent’s well-established QZone, the personal home page.11 Weixin/WeChat Payment, to give another instance, an integrated online payment service, offers further monetization channels for Tencent through online advertising and e-commerce transactions:

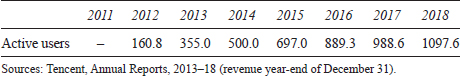

Table 4.2 Weixin and WeChat Combined Monthly Active Users (MAU) (Millions)

QQ Game Portal

Tencent started out entertainment service with casual mini-games, such as “board games, card games and other games of skill” in 2003 through QQ Game Portal, a program bundled with the QQ software package.13 Free to users and giving easy access to basic game services, QQ Game Portal quickly attracted a large number of users and became the largest casual-game portal in China.14 New games, such as QQ Tang (a 2004 collection of a few mini-games for friends), QQ Speed (a self-developed car racing game), and QQ Dancer (a 2008 musical dancing game), were continually launched, and Tencent monetized them by adding fee-based subscriptions and game accessories for purchase.15 In view of its growing popularity, Tencent launched Game Center on both Mobile QQ and Weixin/WeChat in 2013, which immediately contributed over $96.93 million (RMB 600 million) to the revenue in that year.16

Massive Multiplayer Online Games (MMOG)

Another real moneymaker for Tencent was its massive multiplayer online game (MMOG) business. Tencent, on the one hand, actively sought licenses from foreign game developers and imported games permitted under the Chinese regulations.17 According to China’s Ministry of Culture (MOC) regulations on online cultural activities, any party who wanted to operate imported online games in China needed to apply for MOC’s approval of both the contents of and the license contracts for them.18 Tencent brought the first MMOG into China in April 2003, which was Sephiroth, licensed by Korean developer Imazic.19Dungeon and Fighter (DNF)—a well-liked MMOG developed by Neople and Samsung—to give another example, was licensed to Tencent for its Chinese distribution in 2007 and launched in June 2008.20 DNF gained peak concurrent users (PCU) of 1.2 million at the end of that year.

On the other hand, Tencent was also devoted to creating its own MMOG by primarily adopting Chinese storylines. In 2007 Tencent launched its first self-developed MMOG QQ SanGuo, which features the ancient Chinese history of the wars among three kingdoms around ad 220 to 280.21QQ Huaxia, another MMOG launched in the same year, was codeveloped by Tencent and Shenzhen Domain Computer Network Co. Ltd., a Tencent investee company.22 This game was also plotted against the background of an ancient, mythical China.23 More games of this style, such as Silk Road Hero, Hero Island, and World of West, were developed between 2009 and 2011.24

First-Person Shooting (FPS)

In addition to MMOG, Tencent made an effort in developing FPS genre in 2007 when it gained the licensing of CrossFire by Neowiz.25 Launched in 2008, the game achieved one million PCU in 2009, which was a world record.26 Carrying on the success, Tencent introduced another Korean-developed FPS game, A.V.A., in 2010 by working with Neowiz again as its Chinese agent.27

Children’s Games

In July 2010, Tencent entered the children’s game segment by launching Roco Kingdom, which later became an online-gaming community for children from 7 to 14.28 Adapting from the storyline in the game, Tencent later produced a series of animated movies that won a box office of $24.4 million (RMB 150 million).29

As Tencent’s gaming kingdom grew large, the company started an international expansion through mergers and acquisitions. In 2010 it acquired a major stake of 92.78 percent in Riot Games and became the parent company of the U.S.-based online-game developer and publisher of League of Legends, a widely played game across the world.30 In 2015 Riot Games became a wholly owned subsidiary of Tencent.31 In June 2016 Tencent bought a majority stake in Supercell, a Finnish mobile-game developer and the publisher of Clash of Clans, for $8.6 billion.32 The company’s roadmap to becoming a global game giant is discussed further in the following sections.

Besides these superstars in chat platforms and games, in recent years, Tencent has put enormous efforts in the broadly defined cultural industry, including online publication and e-reading, online music and streaming services, and the previously discussed media and movie industry.

Online Publication and Reading Service

Tencent had only launched its own online reading service in 2014.33 In early 2015 Tencent and Shanda formed China Reading Ltd., moving their own online publishing and literature services, namely, Tencent Literature and Shanda Cloudary, together into one company specializing in online publishing and e-book services.34 Shanda Group, founded in Shanghai in 1999, was originally an online game company and became an investment group that focused on “financial services, technology and healthcare sectors.”35 The newly launched China Reading Ltd. was codirected by Tencent Literature’s former CEO Wu Wenhui and Shanda Cloudary’s former CEO Liang Xiaodong. Tencent held a majority 66.4 percent stake in China Reading.36

With Tencent being a latecomer, the deal, more like an acquisition than a merger, made China Reading the largest online publishing and e-book company in China.37 Said to have more than 600 million registered users in China, China Reading in 2017 was planning an initial public offering in Hong Kong.38

Online Music

In July 2016 Tencent partnered with China Music Corp. in promoting the digital music business and acquired a majority stake of 61.6 percent of China Music Corp. The two joined Tencent’s QQ Music and China Music Corporation’s KuGou and Kuwo to form a new company, Tencent Music Entertainment Group, with Tencent’s vice president Pang Kar Shun as CEO and China Music Corporation’s co-CEOs Xie Guomin and Xie Zhenyu as copresidents.39 The alliance created a dominant player in China’s music-streaming market, as China Music Corp. KuGou and Kuwo each occupied 28 percent and 13 percent of the mobile music market, respectively, with another 15 percent owned by QQ Music.40 In addition to a majority market share, the strategic merger was expected to advance the battle against online piracy in China, considering that the combined exclusive content licenses held by Tencent and China Music Corp. represented “more than 60 percent of all available music rights in China.”41

In December 2017, Tencent started a collaboration with the Sweden-based music-streaming giant Spotify through a minority stake exchange, which would allow Spotify and Tencent’s music subsidiary Tencent Music Entertainment (TME) to each hold a minority equity stake in the other.42 In the following October, Tencent Music Entertainment (TME) filed an IPO prospectus, at which time Tencent owned 58.1% of TME’s shares and Spotify owned 9.1 percent. TME became publicly traded at NYSE on December 12, 2018.43

From QQ to WeChat

For a closer look into the development of QQ and WeChat, next examined are the strategies to promote the QQ brand as a cultural synergy, followed by a discussion on the challenges Tencent encountered, especially with major Chinese telecom carriers.

Building a QQ Community

Taking advantage of QQ’s popularity and user base, Tencent launched a set of fee-based VAS that construct an interactive online community. Users within this community, through purchasing different services, are able to individualize their virtual profiles, interact with friends or strangers, and play casual games, among other activities, all of which were centered around the QQ brand, such as Premium QQ, QQ Show, QQ Fantasy, QQ Pet, QQ Magic, QQ Ring, QQ Farm, and QQ Ranch, to name a few.44 The QQ-related VAS have become a new time-space for self-display, self-expression, relationship maintenance and establishment, and entertainment.45

Tencent launched QQ Membership Club in November 2000, which was a higher-level IM service based on a monthly membership fee.46 By paying a monthly charge of $1.20 (RMB 10.00), users were able to buy additional services to individualize their QQ usage, such as the ability to choose their own QQ numbers, store message logs on QQ servers, to have 100 megabytes storage space, free credits to use various QQ VAS (including online entertainment services), special signs indicating their QQ membership status, and exclusive access to additional chat rooms.47 To take a QQ number as an example, when a user registers a free QQ account, the program would randomly assign the user a unique identification number. A member who pays a premium fee could choose a specific number, very often one that represented a date with special meaning, such as a birthday or anniversary. The service has gotten so popular that Tencent now has an entire website—haoma.com—to manage the selling and issuing of customized QQ numbers. Some parents would even buy a QQ number for their yet-to-be-born children as a gift based on the date and time of birth. Romantic partners would choose a QQ number that symbolizes their relationship.48 In a way, QQ is no longer just a chat tool but is sold and exchanged as a commodity that represents the consumer’s name and identity online.

The fee-based QQ membership later developed into a tier-based system that is integrated into every aspect of Tencent’s value-added services. The system has nine tiers from “ordinary users” to “SVIP8,” each level enjoying a different set of benefits and privileges.49 For example, an ordinary user without paying any premium fee can have up to 500 QQ friends and 2G online storage. At SVIP8, the highest level, the user is able to have up to 2,000 QQ friends, two chatting groups of 2,000 people, storage of up to 1,400 personalized stickers on the account, a 500G online photo album, 2.5T online storage, and 350 QQ coins redeemable for other services within the QQ system.50 All of these symbolize a privileged “social-economic status” in the QQ universe. Other similar privileges relate to gaming, shopping, and decoration in Tencent’s online community.51 Gaming privileges, for instance, include early access to newly released games and free toolkit packages for game use, promotions, and discounts, among others; shopping privileges connect online lifestyles to offline activities by providing users with offline shopping coupons; users could also customize their account skins, decorate homepages, and individualize profile avatars.52

To implement the premium membership system, a variety of micro- applications installed in QQ software let users customize their profile pictures and message-notification ringtones, play casual games, raise virtual pets, and so on. QQ Show, one of the earliest and most successful micro-apps, was a virtual avatar system that allowed users to choose an individual virtual character and pay for “virtual clothing, hairstyles, scenes and accessories” to decorate their profile images.53 The service was carried out in January 2003 and commercially run two months later.54 Tencent promoted the service by first providing particular QQ Show items free. The company gradually introduced new features to the service with different levels of charges.55

Rivals in IM

As discussed in Chapter 2, the success of QQ was partly owed to Tencent’s partnership with major Chinese telecom carriers who allowed mobile QQ to be preinstalled on their mobile SIM cards. At the same time when Tencent collaborated with China Mobile, China Unicom, and China Telecom, these giants to different extents felt the threat posed by Tencent’s mobile QQ, which provided text messaging, voice communication, and visual exchanges, among other VAS, at a price lower than the common charges through traditional telecom channels.

These state-backed telecom titans first approached the problem by renegotiating terms in their partnerships with Tencent. In October 2004, as former Tencent executive Chengmin Liu related, China Mobile called for a sudden meeting with Tencent and asked to redefine the rates collected out of one MVAS—the 161 Mobile Chat.56 According to Liu, the 161 Mobile Chat represented a significant portion of Tencent’s overall earnings, which left Tencent little bargaining power with China Mobile.57 On December 22, 2004, Tencent announced in an official release that it was in negotiations with China Mobile on the matter.58 In view of the fact that 161 Mobile Chat contributed 10 percent and 16 percent of Tencent’s net profit in the calendar year 2003 and the half year ended June 30, 2004, respectively, Tencent’s monthly net profit from 161 Mobile Chat would be reduced by approximately $484,000 (RMB 4 million) with China Mobile’s new terms.59 In January 2005, the two companies terminated their shared fee-collection agreements, and Tencent only received “a predetermined monthly maintenance fee” until the end of June 2005.60

As a result, revenues immediately declined in Tencent’s mobile and telecommunication sectors: “Revenues from our mobile and telecommunications value-added services decreased by 19.3 percent to RMB 517.3 million for the year ended 31 December 2005 from RMB 641.2 million for the year ended 31 December 2004.”61

A collateral damage was the unprecedented drop of Tencent’s stock price, which fell by over 8 percent during negotiations with China Mobile in December 2004.62 During the next two years, Tencent engaged in an array of buyback and repurchase of its own shares.63 Analysts said that this was aimed to show the company’s confidence in its continual growth.64

A second move, taken by telecom carriers, was to start their own instant-messaging products. As early as 2003, China Telecom started developing Vnet Messenger (VIM), a service to connect landline phones, lower-end cell phones (Little Smart), and mobile phones for chatting, document transmission, and video chatting.65 Little Smart ran on a much-cheaper technology than GSM or CDMA and “used wireless local loop (WILL) technology to connect mobile devices with traditional landline networks, with its own set of base stations, switchers, and handsets.”66 Bound with China Telecom’s broadband services, VIM was also an integral platform for entertainment VAS, such as browsing pictures and downloading ringtones and mobile games for household desktops. “It was a reasonable move for China Telecom to develop its own IM,” according to one VIM R&D staff member, commenting on the growing threats that traditional phone services were faced with.67 Not enough data suggests whether VIM was a successful move or not. Upon its acquisition of China Unicom’s CDMA business in 2008, China Telecom, with the 3G licenses granted by the state, launched a new mobile and desktop IM app—e-Surfing live—that integrated instant information services with voice and data communication.68

China Telecom was not alone. In 2006 and 2007, China Mobile and China Unicom both developed their own instant-messaging systems. China Mobile launched a mobile-to-PC IM service, Fetion. Initially, an IM platform only for China Mobile’s cell-phone subscribers who were able to exchange messages between computers and cell phones, Fetion enjoyed a dramatic growth during Tencent’s fight with Qihoo 360 and eventually opened up to all mobile users, including those of China Unicom and China Telecom in November 2010.69 China Unicom, on the other side, launched a mobile-Internet instant-messaging app, Chaoxin, in 2007, which was later shut down in 2009 when its CDMA business was relocated to China Telecom.70

At the end of 2006, Tencent and China Mobile revisited their terms of collaborations on Mobile QQ. Prior to this, China Mobile was said to have terminated collaborations with all major IM service providers, including Tencent, in order to promote its own IM application.71 The negotiation resulted in a “cooperation memorandum” to jointly develop the two companies’ IM platforms and to extend their contracts for another half a year, during which they would together launch Fetion QQ.72 According to the plan, Fetion QQ would realize the “interconnection between China Mobile’s Fetion handset users and QQ subscribers.”73

Debate on Weixin/WeChat

The coexistence of QQ, Fetion, and other mobile messaging apps remained for several years until January 2011, when Tencent launched its mobile social application Weixin/WeChat as an integral site for free text and multimedia messages, video calls, photo sharing, mobile games, e-commerce, and e-life, among others.74 Telecom carriers’ SMS took an immediate hit, as Weixin/WeChat provided convenient text-message service at a much lower price than SMS. Traditionally, SMS was charged according to the number of messages sent. One message, regardless of length, was $0.01 (RMB 0.1). The cost of Weixin/WeChat, however, was based on the amount of the data traffic through general packet radio service (GPRS). For every 1 MB of data streamed via GPRS, users could send thousands of text messages by Weixin/WeChat and only be charged a total of $0.15 (RMB 1.00).75 Weixin/WeChat, quickly diffused among QQ users, is said to have taken away 20 percent of the SMS businesses immediately, which totaled half a year’s profits for China Unicom and China Telecom combined in 2011.76 Taking the hit hard, China Unicom and China Mobile launched their own Weixin-like mobile applications in 2011, WO and Feiliao, respectively. Neither turned out to be a noticeable counterweight to Tencent’s Weixin/WeChat. In July 2013 China Mobile aborted its Feiliao business, while China Unicom chose to work with Tencent in promoting the customized SIM card for packaged deals of Weixin/WeChat services.77

The challenge posed by over-the-top content (OTT) providers to traditional telecom carriers did not stand out as a unique phenomenon in China. It was a natural trend because the growing Internet industry would want to expand both horizontally and vertically and to enlarge business territory. It was essentially a battle between the different units of capital for the limited resources possessed by users. Dong-Hee Shin analyzed the rise of mobile voice over Internet protocol (mVoIP) in Korea that had resulted in a decline in voice calls carried by mobile operators.78 In the European and North American contexts, the growing popularity of social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, and online-streaming platforms, such as Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube, brought similar challenges to telecom and cable operators.79 How the Internet firms and telecom operators negotiated the terms, however, varied depending on the specific context. For Tencent, the triumph of Weixin/WeChat came as a negotiated outcome among the telecom carriers, the Internet companies, and China’s central regulatory entities.

First, the rise of Weixin/WeChat fell along the national strategy to converge three networks—telecommunications, broadcasting and TV network, and the Internet. In January 2010 in a State Council meeting, Premier Wen Jiabao pushed for the integration of the three networks.80 This was not just about reconsolidating national infrastructural networks but an important strategy to further open up domestic communication markets to additional players who were traditionally kept from service provision or content production, such as equipment manufacturer or Internet VAS providers.

The central government made another gesture when in 2014 the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) jointly announced a notice to liberalize pricing of the telecommunications services.81 The message was clear: to further open up the domestic telecom industry, to encourage and protect domestic Internet capital, and to rebalance the national political economy by accelerating the “Chinese-style digital capitalism.”82

It was under this context that MIIT played a critical role in protecting Tencent’s advantage with Weixin/WeChat. In early 2013, there was a heated debate over whether telecom carriers should charge additional fees either on Tencent or users for using Weixin/WeChat, considering how much impact Weixin/WeChat had on the carriers’ SMS services. According to a statistic announced by the MIIT in March 2013, the growth rates of SMS business and telephone business in the first two months of 2013 were much lower than those of the mobile Internet businesses.83 Telecom carriers insisted that there should be additional charges to Tencent for maintaining the network infrastructure because Tencent services took so much advantage of it.84 In February and March 2013, MIIT called for multiple meetings of telecom operators and Tencent to coordinate their requests. MIIT’s attitude, however, was ambiguous and inexplicit. On the one hand, MIIT head Miao Wei acknowledged the validity of telecom carriers’ concerns, as they had to expend money and effort in managing the network. On the other hand, Miao also noted that this problem should be solved by a competitive market mechanism, the principle of which was to contain telecom giants’ monopoly power and to encourage the growth of innovative Internet companies. More of mediation than regulation, MIIT asked China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom not to collude on this matter, and they were instructed to negotiate terms with Tencent separately.85

Under the guideline to “follow the market rule,” MIIT instructed that China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom were not supposed to form an alliance in negotiating with Tencent. Previous telecom history already suggests an enduring rivalry among the three, not to mention their different approaches in responding to the Weixin/WeChat challenge. China Telecom started working with Tencent by launching QQ service on its CDMA mobile devices in as early as 2011.86 Any China Telecom user can use his or her phone number as the QQ numbers to log onto Mobile QQ, along with other services on the mobile phones certified by China Telecom.87 In terms of Weixin/WeChat, China Telecom suggested that it was an opportunity, instead of conflict, for further collaboration in its data business. The president of China Unicom also implied that the relationship with Tencent should be an interdependent one rather than a water-fire antagonism.88 Both China Telecom and China Unicom shortly launched their own versions of contract cell phones with preinstalled Weixin/WeChat. China Mobile, for the moment, was sticking to its own Fetion service.

Game Industry as Game Changer

In a different theater, Tencent used the game sector as an entry point to gain transnational competitiveness. Building upon its advantage in its user base, capital power, and global reach, Tencent was vertically integrated as a global game empire from engine service through game development to production and distribution.

The Chinese Distributor and Operator

Tencent states in its prospectus, “Online games currently are one of the fastest growing online services in China. We develop and source online games for our customers.”89 Collaborating with foreign game developers and publishers, mostly Korea- and U.S.-based, provided a convenient path for Tencent, especially at the company’s infant stage when it was not competitive enough to offer appealing game contents and services. Tencent started representing foreign-developed games as their Chinese distributor and operator in 2003 when it first worked with Korean game company Imazic for the distribution of a massive multiplayer online game (MMOG)—Sephiroth. Sephiroth, the Chinese name of which is QQ Kaixuan, was Tencent’s first MMOG for commercial operation.90 Although a popular one, the game was shut down in 2009 due to the termination of license from Imazic.91

Many of Tencent’s popular games in varying genres were launched through such an importing-distributing-operating strategy, including Korean game publisher Neowiz’s online music-related rollerblade racing game: R2Beat; German game developer Crytek’s first-person-shooter game Warface; Korea-based Webzen’s Battery; Korean company Vertigo Games’ War of the Zombie; Korean developer Nextplay’s popular MMOG Punch Monster; San Francisco-based social-game developer Zynga’s localized Cityville on QZone, among others.92

These collaborations formed a symbiosis between Tencent and foreign game developers. The relationship proved beneficial. For overseas game developers, by taking advantage of Tencent’s local user base, they often found their games to be well accepted in China. For Tencent, securing exclusive licenses of popular online and mobile games from foreign developers and publishers not only attracted more Chinese players to Tencent’s network but also made it convenient to promote Tencent’s own games.93 A seemingly win-win strategy helped to sustain Tencent’s dominance in China’s gaming market, as well as to tighten Tencent’s relation with foreign developers for further collaborations.

Vertical Integration Through Investments

A second and more important strategy that Tencent took—when it had grown bigger—was to acquire minority or majority stakes in other players in the global PC, console, and mobile gaming markets.94 The first move of this kind was in 2006 when Tencent bought 16.9 percent of the equity interest in GoPets Ltd., a Korean corporation that developed and published interactive games, such as raising virtual pets.95 Between 2008 and 2010, Tencent invested in a few online and mobile-game developers, though the details of the deals are scant. Among them, Tencent gained 20.02 percent of equity interest in a “Southeast Asia-based online game company” in 2008 and raised its stake to 30.02 percent as of the end of 2009.96 In 2010 alone, Tencent acquired equity interests in seven online-game development firms based in Southeast Asia, East Asia, or the United States, based with varying stakes from 10 percent to 49 percent.97

Whereas these unspecified deals involved small expenditures, Tencent launched some large-scale mergers and acquisitions beginning in 2011. These displayed distinctive characteristics of vertical integration in the gaming industry.

In 2012 and 2013 Tencent purchased enough equity to ultimately own 67 percent of Level Up, the online game and game-magazine publisher, mentioned in Chapter 3, that primarily operated in the Philippines, India, Brazil, and some other parts of Latin America.98 The deal helped Tencent “identify further opportunities in” the emerging markets of Brazil and the Philippines.99 Tencent’s game distributing businesses, since 2012, further extended into Activision Blizzard’s territory. Activision Blizzard, “the world’s most profitable pure-play game publisher and a global leader in interactive entertainment,” set foot in China by collaborating with Tencent for its blockbuster franchise Call of Duty.100 In addition to an exclusive license to operate Call of Duty in Mainland China, Tencent also subscribed a 6 percent partnership interest in Activision Blizzard with about $429 million (RMB 2.638 billion).101 While Tencent’s effort to explore distribution rights for various games was ongoing, in 2017 Tencent achieved another landmark victory when it won the right to publish that year’s blockbuster online multiplayer battle royale game PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) in China on mobile and smart platforms.102

Then Tencent moved upstream in the business chain by entering the game-engine market, which would provide the technical and, especially, software support for game visualization in various genres and settings.103 This was primarily achieved through Tencent’s investment in the U.S.-incorporated Epic Games. In July 2012 Tencent acquired 48.4 percent of equity shares in Epic Games, which specializes in 3D game-engine technology and had reputable collaborations with Electronic Arts (EA).104

Even greater efforts were put in expanding into the game-development sector—a main battlefield in the industry—both in online and mobile businesses. Riot Games, a U.S.-based developer and publisher of the well-known massive online battle arena (MOBA) game League of Legends, which boasted more than 100 million monthly active players as of September 2016, became a wholly owned subsidiary of Tencent as of the end of 2015.105 The acquisition was achieved through a series of arrangements initiated since 2008. In November 2008 the two companies entered into a licensing partnership that gave Tencent the exclusive license to distribute Riot Games’ under-development title League of Legends: Clash of Fates.106 In February 2011 Tencent strengthened its links to the widely distributed game by acquiring a majority interest of 92.78 percent in Riot Games, prior to which Tencent held a minority of 22.34 percent.107 Subsequent to the deal, Tencent was set for the beta opening of League of Legends in China while Riot Games remained independent in its own operations and management.108 In 2015 Tencent acquired the remaining shares of Riot Games and became its parent company.109

In 2015 Tencent further expanded in the U.S. market by acquiring 14.6 percent stake in Glu Mobile, a San Francisco-based mobile-game developer.110 The deal was closed at an 11 percent premium to Glu’s closing price at the time, as Tencent paid $126 million for 21 million shares.111 As a result of the partnership, Steven Ma, Tencent’s senior vice president for the interactive entertainment division, joined Glu’s board of directors in April 2015. Although Glu Mobile was famous for its mobile games associated with celebrities, such as Kim Kardashian: Hollywood and Gordon Ramsay: DASH, the collaboration was aimed at bringing Tencent’s Weixin/WeChat-based smartphone shooter game—WeFire—to overseas markets, including North and South America, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and others.112

In the Asian market, through a range of agreements in 2014, Tencent bought around 28 percent interest in a Korean online and mobile-game developer and publisher, Netmarble Games Corp., better known by its former name CJ Games Corp.113

At the same time, integration into the mobile-gaming sector was consolidated when a high-profile trade—its buy-in in Supercell, the developer of the hit game Clash of Clans—took place in mid-2016.114 With a record-breaking price of $8.6 billion, Tencent bought the Finland-based company from SoftBank, the Japanese telecommunications and Internet corporation that was an important institutional shareholder of the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba.115 While Supercell strengthened Tencent’s arm in mobile gaming with the popular and fast-growing Clash of Clans, the strategic partnership also gave Supercell access to “hundreds of millions of new gamers via Tencent’s channels” in China.116

As a unique arena of global and local cultural interactions, the digital gaming industry has become a potentially strategic market in transnational capitalism. Tencent, through a carefully unfolding and integrating process, was able to position itself as an important force transnationally in the game industry, more than in other submarkets of the Internet industry, such as IM or social media. The game sector, in this sense, was prospectively a critical “game changer” in Tencent’s reach for global power.

Transnationalizing the Tencent Brand

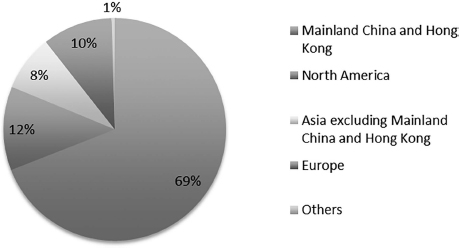

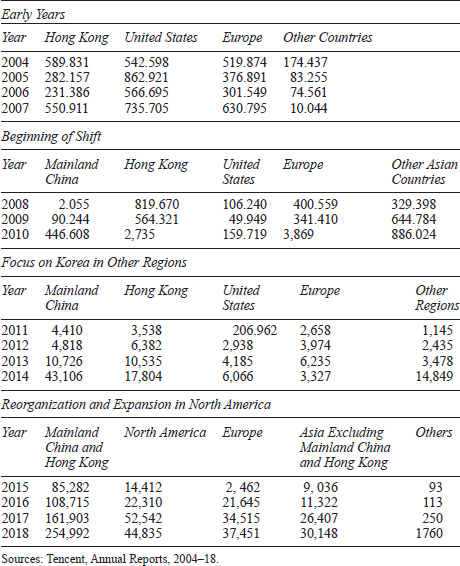

Tencent’s growth in QQ, WeChat, and the game industry showed a clear path to extend its influences from domestic to global markets. As Tencent started incorporating transnational elements into its capital structure at an early stage—two years after the company’s birth, the company was active in making overseas investments. According to the company’s reports in past years, it had investments, aside from Mainland China and Hong Kong, in North America, Asia, Europe, and other parts of the world. The company rearranged the ways to present overseas investments by regions a few times. Table 4.3 shows Tencent’s overseas investments in four sections, which reveal the way the company organized its foreign businesses and reflect shifts in Tencent’s business focus throughout the years.

Table 4.3 Tencent’s Yearly Investments by Region, 2004–18 (RMB Million)

As revealed by the company’s financial reports since 2004, early years’ investments, between 2004 and 2007, were primarily in financial instruments, such as “held-to-maturity investments, trading investments, term deposits and cash and cash equivalents.”117 By comparing volumes to those in later years, the early years’ financial investments were not as significant as the business deals Tencent later made. In 2008 investments in associates and, particularly, in Southeast Asian countries begin to stand out as a major focus.

Korea was the focus for 2013 and 2014. Of the $562 million (RMB 3.5 billion) invested in other regions in 2013, $279 million (RMB 1.8 billion) went into Korea. In 2014, of the $2.4 billion (RMB 14.8 billion) invested in other regions, $1.1 billion (RMB 6.4 billion) went to Korea.

In recent years, investments expanded to both financial and nonfinancial forms, such as associates, redeemable preference shares of associates, joint ventures, and available-for-sale financial assets.118 In 2015 Tencent reorganized its spreadsheet again by putting Mainland China and Hong Kong together, enlarging the United States into the North American region, and adding another section on other Asian areas excluding Mainland China and Hong Kong.

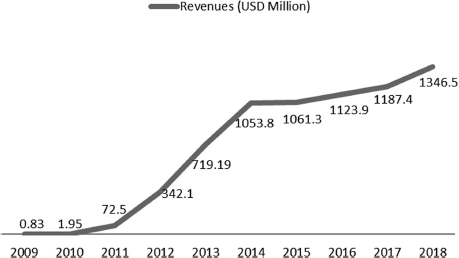

On the revenue side, as of 2018, the revenue from overseas markets was $1.35 billion (RMB 9.037 billion), accounting for 2.9 percent of Tencent’s total revenues.

|

Year |

Revenue (RMB Million) |

Percentage of Total Revenue |

|

2009 |

5.649 |

0.05 |

|

2010 |

13.914 |

0.07 |

|

2011 |

468.556 |

1.6 |

|

2012 |

2,158.610 |

4.9 |

|

2013 |

4,459 |

7.4 |

|

2014 |

6,470 |

8.2 |

|

2015 |

6,612 |

6.4 |

|

2016 |

7,566 |

4.9 |

|

2017 |

7,993 |

3.4 |

|

2018 |

9,037 |

2.89 |

Sources: Tencent, Annual Reports, 2009–18.

Figure 4.2 Tencent’s Yearly Revenues Outside China, 2009–18

Sources: Tencent, Annual Reports, 2009–18.

Transnational activities took a variety of forms: market expansion of Tencent’s services, investments in or acquisitions of foreign-based media and digital companies by purchasing stakes in them, research and development collaboration in working on data centers and network systems, strategic partnerships with foreign-based companies in jointly developing services, and strategic memoranda with giants from different media industries, among others.

Market expansion was primarily through the use of Tencent’s IM services and value-added services of QQ, micro-blogging, QZone, and WeChat. Tencent achieved this in several ways. First, it launched its services in multiple foreign languages. In December 2010 Tencent launched the first international version of QQ in English, Japanese, and French.119 In 2011 Tencent launched the English service for its microblogging site.120 For WeChat, the service in 2012 was available in two South Asia countries—India and Thailand.121 As of 2018, WeChat was offered in 18 languages, including English, Indonesian, Spanish, Portuguese, Thai, Vietnamese, and Russian, and had over 70 million registered overseas users. In particular, WeChat enjoyed high popularity in South and Southeast Asian countries, such as India, Thailand, and Malaysia.122

Secondly, Tencent collaborated with local media companies and Internet service providers to both promote publicities and diffuse its products. In Indonesia, Tencent partnered with Indonesia PT Global Mediacom to launch a TV commercial campaign for WeChat in 2013.123 The company even recruited soccer stars Lionel Messi of Argentina and Neymar da Silva Santos Júnior (Neymar) from Brazil for WeChat commercials.124 Such an approach was made loud and clear when Ma Huateng revealed his plan to expand WeChat services and localized it by adapting it to Western users: “[The next step] will be to cooperate with local developers, for example with game developers to promote products, and also to adjust to Western user habits.”125 In late 2015 WeChat took another step further when its online payment service started fully opening to overseas purchases so that users could pay with RMB using WeChat, and the vendors would receive local currency for the transactions.126

In addition to the instant-messaging and social-media businesses, many investments, acquisitions, and strategic partnerships focused on games, unsurprisingly, with developers primarily based in South Korea and the West Coast of the United States. Tencent’s intensive efforts put forward in the global game industry did not fully kick off until 2008, when it first invested $11 million in the San Francisco-based online-game company Outspark, together with two other investment partners, DCM and Altos Ventures.127 Some major investments, as disclosed previously, include alliances with Zynga, Riot Games, Epic Games, Activision Blizzard, Netmarble Games, and Supercell, among others.

Last but not least, strategic partnerships with foreign media-content providers suggest a clear ambition of Tencent to enter cultural industry and, specifically, content production.128 The first step the company took was to become an exclusive partner with U.S.-based TV, film, and music corporations and provide paid online-streaming services of their contents to Chinese users. Between 2013 and 2016, Tencent secured exclusive distribution licenses from Warner Bros. Pictures, Warner Music, Universal Studios, Miramax Films, Lionsgate, Pixar Studios, Marvel Studios, Sony Music Entertainment, HBO, Paramount, MGM, Walt Disney, 20th Century Fox, and ESPN’s NBA, NCAA Men’s Basketball Championship Tournament, and the X Games.129 These partnerships altogether built up Tencent’s online-streaming kingdom as a unique content provider and distributor of the major Hollywood productions.

Conclusion

Tencent’s cultural profile further exemplifies its strategy of integration and transnationalization. The brand’s star products in instant messaging and chatting, including QQ, Weixin, and WeChat, have together successfully built an online community and cultural identity for Chinese users. While its mobile chat is primarily grounded on a popular domestic base, Tencent’s establishment in the gaming industry has taken full advantage of its global collaborators as their distributors, operators, codevelopers, and/or investors.

The company’s overall transnational expansion has unfolded gradually since its public offering in 2004 and featured a full-scale strategy that incorporated various forms of inter-capital relations, such as mergers and acquisitions, strategic alliances, service expansions, and research and development. With IM and gaming being two primary vectors, Tencent’s IM and social-media services are predominantly expanded into South and Southeast Asia, while the collaborations and investments in the gaming sector are connected more closely with the capital units from the United States and Korea. Recent moves into media and cultural markets suggest a further diversification of Tencent’s businesses.