3 Fruit Trees

Possible Uses

Fruit trees and bushes fulfil a number of functions within my permaculture system. They provide vitamin-rich, healthy food, which can be processed to create many different products such as jams, preserves, juices, vinegar, wine, spirits etc. Fruit trees are also very well suited to growing in paddocks where livestock is kept, because they are an excellent source of food. The windfall fruit make an especially good source of high quality feed for pigs. The fruit blossoms provide a great number of insects with a rich source of food. Bees, which play a substantial role in pollinating fruit trees, particularly benefit from the fruit blossoms. If there are enough bee colonies nearby, the number of pollinated flowers will increase dramatically along with the size of the yield. Wood from fruit trees (mostly wild fruit trees), and especially from pear and cherry trees, is highly valued as top quality joinery and industrial timber. The roots are very popular with artists, because the burl wood can be used to make unique and beautifully shaped objects such as wood carvings or other works of art. The aesthetic value of the trees should also be considered. From spring to winter, a blossoming, fragrant orchard in fruit brings joy to the heart and soul every time you walk through it.

Planting fruit trees costs me no more than planting any other kind of tree. The costs are not higher when I plant an orchard, because I just sow the trees and then graft the varieties I want to grow. If you use this method, you will need to have a great deal of patience, because it will take a long time for the trees to give their first yield. As fruit trees have so many advantages, I try to grow as many of them on my land as possible. I can use all of my terraces for growing fruit trees, crops and for keeping livestock at the same time.

I also plant cultivated and wild fruit trees in the forest to increase the diversity of species there and to increase the range of functions available for my woodland plots. From my point of view, there is no reason not to simply plant fruit trees (cultivated and wild) together in a mixed culture in the forest. In the state of Tirol, at least, the authorities agree with me on this point: a young farmer told me about a business consultation in which the introduction of wild fruit trees was being actively encouraged near the town of Kufstein using the striking tag line ‘jewels of the forest’. If all authorities were of the same opinion, I could have saved myself many disputes and a great deal of time and frustration.

Fruit trees in blossom are not just pleasing to the eye;

they also make excellent honey plants.

On the Krameterhof there are several thousand fruit trees of different varieties and sizes. Selling fruit trees and bushes has been one of the farm’s most important sources of income for some time. I have overseen the design and planting of many gardens, recreational areas and public grounds (from parks and playgrounds to cemeteries). As my trees are not sprayed with pesticides, fertilised, watered or pruned, they must develop into hardy and independent trees in order to grow and thrive under these conditions. Over the course of time, they have also adapted themselves well to the climatic conditions in Lungau where there are large temperature differences during the day and at night and a greater danger of frost. This is why I have been able to guarantee that my trees would grow well the year they were planted and the next without taking any great risk. I knew that failure would be unlikely as long as I planted the trees myself and the owner followed my instructions: leave the trees alone as much as possible and do not tend them excessively. This guarantee has given me a large commercial advantage, because I was the only one who was able to give a guarantee of this kind and the only one to agree to replace any trees that did not grow. These days I do not have the time to sell trees individually or to take on small planting jobs, despite the demand still being very high. Time constraints mean that I can only oversee a few of the larger and more interesting projects, which my plants are best suited for.

Many fruit trees have been planted throughout the Krameterhof. They have also been planted on steep and rocky terrain, because they help to stabilise the slope with their deep roots, which provides valuable security. Naturally, these trees are not for sale, instead they stay where they have been planted. The fruit here is either harvested, if the land is easily accessible, we have the time or there is demand for it, or it falls from the tree and provides the animals with food. On these areas of land old and rare fruit varieties, which generate a lot of interest from distilleries, are generally grown. My Subira pears, for example, are much sought after in the production of schnapps. When I sell them I arrange that the buyer harvests the pears themselves. This means that I only have to give the distilleries the correct harvesting time. Then they send people to harvest the fruit and still pay a good price for this hard-to-find pear variety. At this altitude they develop a very intense flavour, which enhances the quality and taste of the schnapps.

Terrace with pear trees that is also used to grow cereal crops (ancient rye).

Cherry trees next to rowan trees, spruces, larches and Swiss pines.

A healthy mixture of cultivated and wild fruit trees grow throughout the Krameterhof. Wild fruit trees can pollinate many cultivated fruit trees. Wild fruit trees are very good for making schnapps and vinegar. They can also be used for making jams and juices and for medicinal purposes. I particularly like to plant:

- Crab apple (Malus sylvestris)

- Wild pear (Pyrus pyraster)

- Wild cherry (Prunus avium)

- Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa)

- Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia)

- Wild service (Sorbus torminalis)

- Service tree (Sorbus domestica)

- Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas)

- Snowy mespilus (Amelanchier ovalis)

View of fruit tree terraces on the Krameterhof. The different flowering times prevents a complete crop failure from late frosts.

As the trees grow in a mixed culture, they blossom at different times, which means that a complete crop failure is prevented if the climatic conditions are unfavourable (late frost). This diversity and the different flowering times ensures that there is plenty of pollen available for the blossoms to be pollinated, which will ensure a good yield of fruit.

The Wrong Way to Cultivate Fruit Trees

From my childhood to this day I have sown, planted and tended thousands of trees. Even as a child I was sorry for every twig I had to cut. This meant that I was always a little negligent when it came to pruning my trees. As a result, a sort of wilderness developed in my first garden, the Beißwurmboanling, over a period of time. During my training to become an arborist at agricultural school, I learnt that fruit trees should supposedly be pruned, fertilised and sprayed with pesticides in order for them to grow well. We were also shown how to catch, poison and gas voles to prevent them from damaging the fruit trees. It is shocking that these practices are still described in almost all textbooks today.

During my training I also learnt about the conventional view of how fruit trees should be planted: for instance, we dug a hole for a fruit tree measuring one metre across and 40-50 cm deep. Then we put in galvanised wire mesh, which was bent at the edges to keep the voles away from the roots, and filled in earth around the tree. The earth was first mixed with a shovel’s worth of chemical fertiliser and a great deal of water. After that, we hammered in a stake and tied the tree to it with a leather strap in a figure of eight. Then branches at an angle of less than 45 degrees from the trunk for apple trees and a 60-degree angle for pear trees were removed. We cut each branch back to an outward-facing bud. This is intended to make the branches grow outwards from the tree. Most of the inner branches were also removed, so that more sunlight could reach the crown. This is meant to help the fruit to develop better. The branches of pear trees are at an angle of 60 degrees, because they have deep roots, which means that the tree can support branches at a steeper angle. The sturdy stake is meant to stabilise the tree so that it is kept upright and grows better. Wind and snow will not bring it down so easily. This sounds quite plausible. Poisoning and gassing voles also makes sense – they eat the tree roots. They will, however, do this in spite of the wire mesh, because they often dig straight down from above. It is also possible that in time the mesh will rust and no longer be capable of protecting the roots.

The intensive use of fertiliser when the tree is planted is supposed to help it grow. The pesticides to protect the tree from fungal diseases and many different kinds of ‘pests’ are, according to experts, also justified. The economical argument should be clear to any layperson. The measures described here to ‘tend’ fruit trees require a great deal of energy and ensure that the trees will continue to need constant care. Trees cultivated in this way are dependent on human care from the first day. They are ‘addicted’ to regular fertilising and watering and they are susceptible to scab, fungus and frost. They are easily damaged by the wind or snow and they are vulnerable to ‘pests’ of every kind. According to the rules of these conventional methods, cultivating fruit trees at high altitudes should not be possible at all.

Healthy tree in my ‘wilderness garden’.

When I finished my training, I received a certificate to allow me to purchase the strongest poisons like parathion. We used these poisons during training. Once I had internalised the conventional methods, I became almost ashamed that I had a wilderness garden at home. So I practised what I had been taught immediately and ‘tidied it up’. The trees were pruned, sprayed with pesticides and fertilised. I bought chemical fertiliser and I bought mouse poison and gas from the chemist’s by the kilogram. I removed the turf in a radius of one meter around each tree, hammered in stakes and tied the trees to them tightly. I cut the espalier trees on the wall of the house back vigorously and bound them tightly to the frame. I continued to remove any grass that grew within one meter of each tree. The voles that I could not reach with poison or gas, I gassed with my moped by directing the fumes from the exhaust pipe through a tube into the entrance of the voles’ burrows. This was also a recommendation given by my school. I carried out these tasks for a whole year with great energy. I also used these methods on my customers’ fruit trees, of which there were many. The following year, I discovered that all of my espalier trees were in a pitiful state. Although a few of them had put out new shoots at the sides or close to the ground, the apricot and peach trees were no longer showing any signs of life. I despaired, because I could not work out what the cause of all of this damage was. I had done everything according to the textbook! When I visited my customers in the spring to sell to them and to prune, fertilise and spray the fruit trees with pesticides, it suddenly occurred to me. At the Schuster-Bartl’s farm in Ramingstein, with whom I have had good business for many years and who have always welcomed me, suddenly the reception was very cold. Mrs Schuster-Bartl – she was well known for being a very strong-willed farmer – greeted me with the words: “Aha, here he comes! You’re the one who ruined everything with your chemical fertiliser and pruning everything back. Well, have a look at what you’ve done: the espalier tree is dead, one apple tree’s had all its branches broken by snow and the young trees have all been killed off by the frost! You’ll be the one paying for all of this damage!” It came as a real shock to me. Of course, I could not say that most of my plants at home were also dead, otherwise I would have had to pay for the damage inflicted everywhere.

Thank heavens there were customers I had not visited that year and so were spared my ‘expert advice’. These customers were completely fine. Once I saw this I breathed a sigh of relief and decided to clear my head and forget what I had learnt. This put me back on the right track. Mrs Schuster-Bartl was completely right: the harsh pruning and the large amounts of fertiliser made the trees grow quickly. However, the branches could not lignify properly, so that they could not grow in the extreme temperatures we have in Lungau. I turned independent and healthy trees into dependent addicts and my harsh pruning only mutilated them. It was a great piece of luck that my practical experiences helped me to find my way back to the right and natural path.

My Method

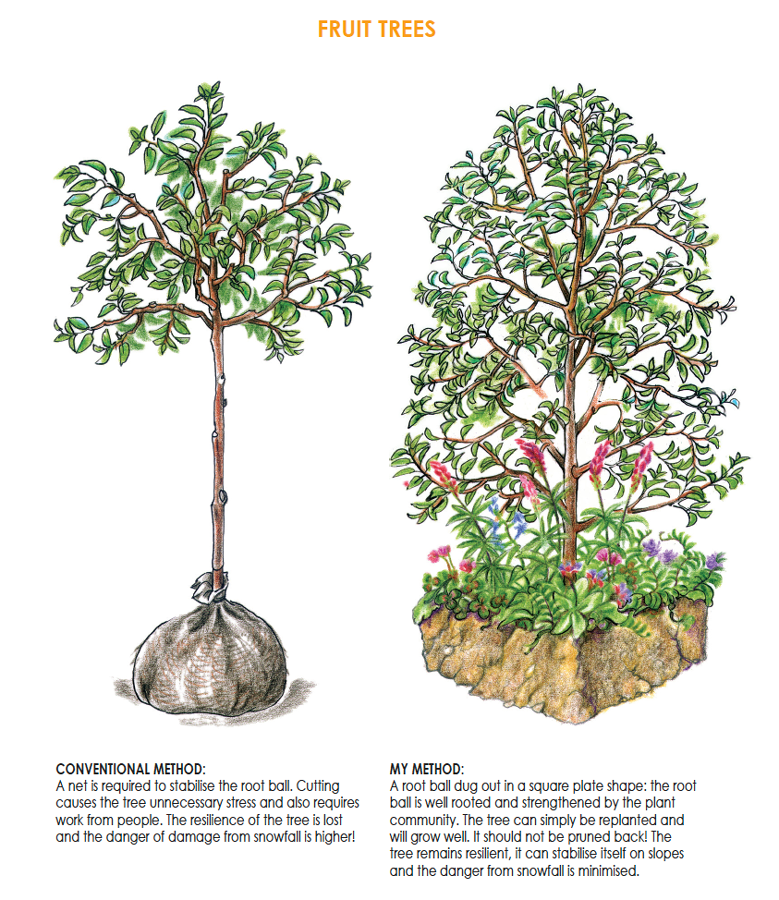

According to my method of planting fruit trees you should leave all of the branches below the graft intact. This means that you should not cut them off! Also you do not dig a metre-deep hole, attach a tree guard, hammer in a stake or use chemical fertiliser. When I plant trees I just dig them in well and cover the area with mulch or with nearby stones. The layer of mulch holds in moisture, rots down and serves as fertiliser. The stones stabilise the tree by weighing down the roots. The stones ‘sweat’, in other words condensation collects underneath them, which is helpful for the newly planted tree. The stones also balance out the temperature. Finally, large numbers of worms can be found under them and these provide the tree with valuable and nutrient-rich worm casts. Many other important helpers like lizards, slow worms and ground beetles find a suitable habitat between the stones. Once I have planted the tree, I sow the seeds of soil-improving plants around it. Deep-rooted pioneer plants like lupins, sweet clover, lucerne and broom are particularly suitable. Their deep roots help to aerate the soil and prevent water from building up in the topsoil. Fruit trees are particularly sensitive to a build up of water. They become stunted, they no longer give the desired yield and are more susceptible to disease and pests. I am often asked why a particular tree does not grow properly. The reason is usually either that the location is wrong for the tree, whether it is too windy, warm, cold, wet or dry, or that the soil conditions are unfavourable. Compacted soil, above all, makes fruit trees difficult to manage. To improve the local conditions, I create microclimates such as suntraps, windbreaks or raised beds to give the tree the protection from the elements it needs. To improve the condition of the soil, I sow plant communities like those mentioned above. You must always observe trees closely, so that you get a feeling for when they are happy. In the course of time, you will get a good eye for it and recognise straight away by the colour of the leaves and the bark whether a tree is in the right habitat or not. When I replant a tree, I dig the other plants up with it. This way I save myself the work of sowing another area. I dig the root ball up in a square plate shape, which is easy to put down on the ground or replant. The accompanying plants strengthen the root ball and protect the tree from drying out while it is being stored, transported and when it is re-establishing itself. As I do not require a net or mesh, I save myself the work that would otherwise be required when securing the root ball.

The branches sink down under the weight of fruit – this allows sunlight to reach the crown.

As I do not prune the trees, the branches retain their resilience. This means that they can support themselves on the ground when they are weighed down by fruit or snow. The trees can stabilise themselves and they are less likely to grow at an angle. They can adapt themselves to the terrain. When the branches are weighed down by fruit it allows sunlight to reach the crown. However, if I were to prune and fertilise the trees in the way that experts recommend, then they would put the excess energy into growing water sprouts, which results in a vicious circle. If I prune the fruit trees, they lose their resilience. The branches cannot sink when they are weighed down; instead they stick up rigidly in the air. At our kind of altitudes (up to 1,500m above sea level) these branches would not be able to withstand the weight of snow and would break. Too great a load of fruit would have the same result. Pruning the trees also creates wounds, which increase the risk of disease (fungal diseases, fire blight). It also causes unnecessary stress to the tree and requires a great deal of work from people. It is a shame that I did not plant fruit trees on the mountain pasture as a school boy. Twenty years ago, I began to go up to the mountain pasture and sow and plant it with a variety of different fruit trees. Today this fruit is particularly valuable, because the cherries ripen there in September. By this point the harvest is long over at lower altitudes where most cherries are grown, because the early varieties ripen at the end of June. At this altitude plums, pears and apples develop a very intense flavour, because of the harsh nights, so I can get a much higher price for them than fruit grown at lower altitudes. Distillery and vinegar specialists are very aware of these advantages, as well as those who are health conscious. It goes without saying that a culture of this kind contradicts all of the rules of conventional fruit-growing.

The side shoots and branches between the graft and the ground fulfil another important function. They provide protection against browsing. The twigs which are just above the ground are eaten by hares, the ones above are eaten by roe deer and the ones above those by red deer. The animals find food at the right height for them, so they do not damage the trunk. As the deer have free access to most of my polycultures on the Krameterhof and there are many tasty things for them to eat, a great deal of them do wander through, especially as the farm backs onto a large wild area. This means that my fruit trees require additional protection against browsing.

Fruit trees are planted on a newly created terrace. I sow various supporting plants around the trees, which improve the growing conditions for the tree as green manure crops and also provide grazing opportunities for deer as distraction plants.

In the picture, an apricot tree grows surrounded by sunflowers, Jerusalem artichokes, buckwheat, oilseed rape and scorpion weed, among others.

Protection Against Browsing

In general, the need for browsing drops when wild animals find enough food. For this reason, I always sow and plant everything I grow in large enough quantities so that the deer, birds, hares and mice all have something to eat. Nature is fertile enough to provide something for everyone. When humans become too miserly and want everything for themselves, a great battle against our many fellow creatures begins. To prevent large-scale damage from browsing, I introduce a large number of distraction plants, which the animals prefer to my valuable cultivated crops. Many plants like Jerusalem artichokes, various kinds of clover and buckwheat make good distraction plants and I also use them concurrently as green manure crops. A variety of types of fruit bush work well to distract deer and keep them away from the polycultures. To prevent stripping, I plant extra willow trees in the area and especially in front of slopes. The deer much prefer to strip these than the fruit trees, because they are softer and more elastic.

If there is a particularly high danger of browsing and stripping or the area available for cultivation is quite small, it is a good idea to provide additional protection for fruit trees. To do this I use a homemade remedy, which I paint on the trees or simply sprinkle over them. It is made of bone salve (the instructions to make this are in the ‘Gardens’ chapter), linseed oil, slaked lime, fine quartz sand and fresh cow dung. These ingredients are mixed to a spreadable consistency. If I want to sprinkle the salve on the plants, I add more linseed oil and use less sand. It is sprinkled the same way as holy water is in a church. The salve can also be applied with a brush or broom. The bone salve has an intense and long-lasting odour, which repels the deer. The smell gets into the bark and lasts for many years, in a way that is similar to mineral naphtha or beechwood tar, which can also be used instead of the bone salve. As neither naphtha nor beechwood tar have such an intense odour, it is a good idea to mix in singed hair, either pig bristles or cattle hair. To singe the hair, put it in a metal container and light a fire beneath it, so that the hair is singed by the heat. This produces a floury mass, which is then mixed into the salve. The smell of singed hair is only noticeable to humans for a short time, but it continues to be repellent to wild animals and they stay well away from the salve. The linseed oil is made from flax seeds and can also be bought in wholefood shops. The oil helps to bind the different ingredients of the salve together and makes sure that the salve adheres to the bark. The slaked lime is beneficial to the tree, because it emits heat. It also helps to combine the bone salve and other ingredients. The cow dung helps to bulk the salve out. It absorbs the other ingredients well, helps to repel animals and gives the salve a good consistency.

If an animal now tries to eat anything, the obnoxious odour will keep it away. If the smell of the salve begins to fade and the tree is under threat of being browsed, the quartz sand remains and causes an unpleasant sensation between the teeth. Once I observed a deer and her fawn from a raised hide as they tried to eat some of my young fruit trees. I had already sprinkled these trees with the salve. For the first couple of bites I could see no reaction. Then in the next bite there must have been a drop of my salve. The result: all of a sudden the deer began to act as if it were crazy. It gagged, threw its head from side to side, ran forward wildly and tried with all its might to wipe the taste from its mouth on the grass. The fawn reacted in the same way soon afterwards. I was in fits of laughter and had to get down from the raised hide quickly, because I could not hold myself up any longer. I was extremely encouraged by the effect of my salve. Obviously the deer did not like the taste of it at all. The salve has not let me down to this day.

Other possible ways to prevent damage from browsing and stripping are protective plants like wild roses, barberries, blackthorn or other similar thorny or prickly plants. The young shoots of these plants are grazed the most heavily, so they will become bushy and protect the fruit trees behind them.

Fruit Varieties

From my experiments, I have discovered that supposedly very demanding varieties – which, according to the experts, only thrive in warm climates and at low altitudes – can also adjust to high altitudes and give satisfactory yields. For example, Golden Delicious thrives here at 1,400m above sea level and produces large fruit, which store well. You should, therefore, not let yourself be dissuaded from cultivating so-called ‘demanding varieties’ at high altitudes. Naturally, they must be sheltered from the wind and it is important that they grow in climatically advantageous locations. Microclimates, which reflect heat from the sun using stones or bodies of water, for example, and protect the plants from weather extremes by using the effect of structures like hollows or windbreaks, are necessary for this. Under no circumstances should you turn to chemical fertilisers, because this will put the tree out of balance and it will not survive the winter. Fertilised trees grow faster and do not lignify as well as unfertilised ones. This means that they are not as frost resistant. According to expert opinion and literature, fruit growing ends at 1,000m above sea level in Lungau. Despite this, I cultivate a large variety of cultivated and wild fruit trees up to a height of 1,500m above sea level.

It is particularly important to investigate the different local varieties that grow in your area if you wish to grow fruit. These will probably be the best suited to your location. Hardy varieties I have had good experiences with can be found in the following lists. The ripening times given are the average for an altitude from 1,000m above sea level. They depend a great deal on the altitude and climate. The White Transparent apple ripens in the middle of August on the Krameterhof at 1,100m above sea level and can only be stored for a few days. As this variety ripens around St Bartholomew’s Day on 24th August, it is known as ‘Bartholomew’s apple’. The fruit quickly becomes floury and, when harvested late, is barely suitable for pressing. At an altitude of 1,500m, on the other hand, White Transparent apples ripen in September, are much firmer and juicier, can be stored for over a month and are still excellent for pressing. The locations given are only general guidelines and should show where the best conditions for each variety can be found. The condition of poor soils can, however, be improved to a degree with green manure, by sowing supporting plants and creating microclimates. This can allow the majority of varieties to thrive on soils, which first appear to be quite unsuitable. So do not let yourself be discouraged from experimenting and gathering your own experiences with these fruit varieties.

Recommended Old Apple Varieties

Boiken apples: they continue to produce excellent fruit at high altitudes.

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Alkmene |

Grows well on shady slopes, not susceptible to scab, mildew or frost, autumn apple |

Mid-September |

Dessert apple, can only be stored for a short time |

|

Ananas Reinette |

Demanding, small yield and greater chance of canker on wet soil, flowers early, winter apple |

Mid-October, good to eat until March |

Flavour similar to currants, dessert apple |

|

Transparente de Croncels |

Particularly suited to good, loose soils, wood and flowers not vulnerable to late frosts, recommended for high altitudes, good pollinator, flowers early and long, autumn apple |

Beginning of September |

Highly aromatic dessert apple, easily bruised, does not store for long (until October) |

|

Baumann’s Reinette |

Prefers well-aerated soil, espalier tree, quite sensitive to frost, flowers early, winter apple |

October |

Yield is ample and early, firm fruit, dessert apple, good for drying, can be stored until April |

|

Bohnapfel |

Undemanding, prefers slightly damp soil, suited to harsh conditions (not sensitive to frost or wind), flowers late and long, winter apple |

End of October, can be eaten from February to the end of May |

Slightly acid, becomes juicy soon after harvest, good for pressing and cider, good storer |

|

Boiken |

Very undemanding in terms of soil and location, flowers and wood frost hardy, suited to harsh conditions, fruit is wind firm, winter apple |

Middle to end of October |

Sweet and fruity, given favourable conditions can be stored until May |

|

Danziger Kantapfel |

Undemanding, weather resistant, suited to high altitudes, good pollinator, flowers moderately early and long, not vulnerable to scab, winter apple |

Beginning of October (can be eaten off the tree) |

Juicy and aromatic fruit, good for juicing, can be stored until the end of January |

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Gravenstein |

Particularly good on loamy soil, early variety (sensitive to frost), windfall, so should be sheltered from the wind, autumn apple |

Mid-September |

High-quality dessert and juicing apple, stores well (until December) |

|

Jacques Lebel |

Undemanding variety, flowers frost hardy, flowers moderately early and long, good for harsh conditions, but pay attention to wind-sheltering, winter apple |

End of September until mid-October |

Juicy, aromatic fruit, does not bruise easily, dessert apple, also well suited to drying and making cider, stores well (until December) |

|

James Grieve |

Well-aerated soil, also suited to cooler climates, flowers vulnerable to frost, autumn apple |

Beginning of September |

Aromatic and juicy, dessert apple, high yield |

|

Jonathan |

Suited to better quality soils, flowers moderately late, good pollinator, very susceptible to scab and mildew, winter apple |

Beginning of October, good to eat until April |

Rich in vitamin C, good dessert apple, stores well |

|

Kaiser Wilhelm |

Undemanding, flowers and wood frost hardy, well suited to high altitudes, fruit is wind firm, so it can be grown in windy areas, vigorous growth, flowers moderately early and long, winter apple |

End of September until mid-October |

Dessert, juicing and cider apple |

|

Landsberger Reinette |

Prefers wet soil, also suited to high altitudes, flowers long, not sensitive to the elements, suited to windy areas, winter apple |

End of September until mid-October |

Good dessert apple, good for drying, can be stored until January |

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Maunzen |

Undemanding, thrives in harsh conditions and at high altitudes, extremely frost hardy, flowers late, winter apple |

End of October |

Juicy, acid fruit, can be stored until March |

|

Odenwälder |

Undemanding, very hardy, suited to high altitudes, very frost and wood hardy, winter apple |

Beginning of October |

Aromatic and juicy, can be stored until December |

|

Ontario |

Prefers sunny areas, flowers moderately early and long, wood sensitive to frost, well suited to being an espalier tree, resistant to disease and pests, winter apple |

End of October, can be eaten in January |

Refreshing, juicy, acid, high in vitamin C, stores for a long time (until June) |

|

Sheep’s Nose |

Prefers good soil, avoid extreme wet (danger of canker), flowers late, wood and flowers very frost hardy, suited to harsh conditions and high altitudes, winter apple |

End of September until mid-October, good to eat until the end of February |

Mildly aromatic, very good cider apple |

|

Schmidtberger’s Rote |

Prefers wet, heavy soil, can be grown in sunny areas as well as in harsh conditions and at high altitudes, sensitive to overfertilising, winter apple |

Good regular yield every other year in September |

Juicy, acid fruit |

|

Belle de Boskoop |

Vigorous growth, fairly resistant to scab and canker; flowers early (sensitive to frost), winter apple |

Harvest from the end of September to mid-October, can be eaten from December until February |

Acid flavour, dessert and cooking apple, good for pressing |

|

Stark Earliest |

Hardy and undemanding variety, also ripens at high altitudes, early variety |

August (generally before the White Transparent) |

Aromatic, poor soil conditions lead to small fruit |

|

White Transparent |

Early variety, frost hardy (suited to harsh conditions and growing as an espalier), summer apple |

August |

Refreshing and juicy, can only be stored for a short time (around 14 days), dessert apple |

|

Winter Rambo |

Prefers fresh soil, flowers moderately late and long, flowers are resistant to late frost, very resistant to scab, winter apple |

Beginning of October |

Cooking and dessert apple, can be stored until January |

|

Zabergäu Reinette |

Moderately sensitive to frost, will grow on dry soil, low susceptibility to scab, flowers late and long, winter apple |

Middle to end of October |

Sweet and aromatic, dessert apple, large crop, can be stored until March |

Alkmene in full bloom; this apple variety is well suited to shady conditions. In the picture it is being grown as an espalier on the western side of the Krameterhof.

Subira – a rare delicacy highly sought after in the production of schnapps.

Recommended Old Pear Varieties

As a rule, pears should not be harvested late, because they have a tendency to quickly become overripe and they cannot be stored any more. It is important to determine the right time to harvest.

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Beurré Alexandre Lucas |

Undemanding, deals well with frost, suited to high altitudes, good espalier tree, early winter pear |

October |

Sweet, fruity, refreshing dessert pear, stores well (until December) |

|

Colorée de Juillet |

Undemanding, suited to high altitudes, ripens very early |

August |

Cannot be stored, small, sweet fruit |

|

Clapp’s Favourite |

Undemanding, must be sheltered from wind, not too dry, espalier tree, also grows in partial shade, summer pear |

End of August |

Large and juicy |

|

Beurré Hardy |

Undemanding, very vigorous growth, particularly good in wind-sheltered areas (premature windfall), flowers hardy, also suited to high altitudes, autumn pear |

Middle to end of September |

High-quality autumn pear |

|

Comtesse de Paris |

Prefers deep soil, wood is frost hardy, flowers sensitive to late frost, must be sheltered from wind, very good espalier tree |

October |

Tart and aromatic |

|

Beurré Gris |

Undemanding, can be grown in dry and windy areas, relatively small fruit, frost hardy |

September |

Very good for drying |

|

Louise Bonne |

Suited to well-aerated soil, flowers and wood sensitive to frost, wind firm, not in cold or wet areas, danger of scab, good espalier tree, autumn pear |

September |

Aromatic, sweet dessert pear, stores well (until November), very good for drying |

|

Conference Pear |

Undemanding, not sensitive to cold, avoid overly wet soil, autumn pear |

September to mid-October |

Very aromatic, good yield |

|

Souvenir du Congrès |

Undemanding, must be sheltered from wind, particularly suited to harsh conditions, espalier tree, flowers moderately early |

Mid-September until the beginning of October |

Very large fruit |

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Gros Blanquet |

Very undemanding, hardy flowers, hardy variety, suited to harsh conditions, summer pear |

End of July |

Coarse-grained, aromatic, sweet dessert pear, also well suited to cooking |

|

Doyenné Boussoch |

Undemanding, hardy, suited to high altitudes, flowers and wood very resistant to frost, espalier tree, autumn pear |

Mid-September |

Tart, can only be stored for a limited time |

|

Rote Pichelbirne |

Particularly good on deep, wet soil, sensitive to frost, autumn pear |

October |

Juicy and sweet, good for cider and drying |

|

Salzburger Pear |

Suited to well-aerated soil, vulnerable to scab under unfavourable conditions, summer pear |

End of August |

Very aromatic dessert pear |

|

Speckbirne |

Suited to dry soil, flowers early, sensitive to frost |

October to December |

Particularly good for cider, also well suited to drying |

|

Subira |

Undemanding, thrives at high altitudes and in harsh climates |

September |

Exceptionally good for schnapps |

|

Williams’ Bon Chrétien |

Does not need much sun, vulnerable to wind (windfall), still gives good yields in partial shade and at high altitudes, espalier tree, late summer pear |

End of August |

Particularly good flavour, very aromatic |

Recommended Old Damson and Plum Varieties

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Bühler Frühzwetsche |

Undemanding, quite resistant to frost, disease and pests, ripens early |

August |

Juicy, but not very aromatic |

|

Greengage |

Undemanding, also grows on poor soil, wood and flowers quite sensitive to frost, grows in sheltered areas |

September |

Juicy, sweet fruit, cannot self-pollinate, very good for compote and jam |

|

Quetsche |

Suited to damp, warm areas and good soil (if it is too dry the yield and fruit will be small), sensitive to frost, but very good as a windbreak tree, self-pollinating |

End of September to mid-October |

Very sweet and aromatic, can be processed in many different ways |

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Kirke’s |

Undemanding, resistant to cold, well suited to harsh conditions and high altitudes |

September |

Large, sweet, juicy dessert plum, cannot self-pollinate |

|

Czar |

Prefers good wet soil in sheltered areas at high altitudes – ripens properly up to 1,400 m above sea level; hardy, but a little sensitive to frost |

August |

Juicy and mildly aromatic |

|

Wangenheim’s Early Plum |

Undemanding, suited to high altitudes, resistant to frost, ripens fully in harsh conditions, self-pollinating |

Middle to end of August (at low altitudes), mid-September (at high altitudes) |

Juicy |

Wild and Sour Cherries

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Dönnisen’s Gelbe Knorpelkirsche |

Relatively undemanding, its colour means that it is rarely targeted by cherry fruit flies or birds |

End of July |

Firm, pleasantly aromatic yellow-gold fruit with clear juice |

|

Große Prinzessin |

Prefers good, deep soil, keep sheltered from the wind, resistant to cold, flowers moderately early and long |

Mid-July |

Aromatic, bright red with light coloured flesh |

|

Bigarreau Noir |

Prefers well-aerated, loamy and sandy soil, only slightly resistant to frost, good yields in windy conditions and at high altitudes |

Mid-July |

Very sweet, red-brown fruit |

|

Hedelfinger Riesenkirsche |

Adaptable, relatively resistant to frost |

July |

Juicy, dark brown-red fruit |

|

Kassin’s Frühe |

Relatively resistant to frost, flowers early |

June to July |

Sweet to mild, red-brown fruit, well suited to juicing |

|

Morello Cherry |

Very adaptable, relatively undemanding, needs little sun, will thrive in wet places in partial shade (north-facing slopes, windy areas), wood is frost hardy, good pollinator, flowers very late |

Beginning of August |

Acid and tart, reddish-brown fruit, well suited to the production of juice, wine, compote and jam |

|

Schneider’s Späte Knorpelkirsche |

Undemanding in terms of soil, quite sensitive to frost, flowers late |

End of July to the beginning of August |

Mild, reddish coloured fruit |

Apricot and Peach Varieties

I particularly recommend ungrafted local varieties like the ungrafted vineyard peach, as it is less susceptible to leaf curl, a disease dreaded by peach growers.

|

Variety |

Location and Characteristics |

Ripening Time |

Fruit Characteristics |

|

Hungarian Best (Apricot) |

Undemanding, will grow on poor soil, relatively resistant to cold, but vulnerable to late frost, flowers early, self-pollinating |

End of July to August |

Excellent for the production of jam and compote |

|

Kernechter vom Vorgebirge (Peach) |

Relatively undemanding, lives long, quite resistant to the elements |

Mid-September |

Sweet to tart flavour |

Wangenheim’s Early Plum

Propagating and Grafting

Cultivated fruit trees are not usually propagated using seeds, because the characteristics of the desired variety will not be passed on true through the seeds. This quality has been encouraged to the extent that many fruit cultivars can now only be pollinated by different varieties. This means that every flower, and therefore every fruit, can produce different seeds and consequently different characteristics. So, if you want to preserve the qualities of a certain variety, you must propagate it vegetatively. Grafting is fundamentally vegetative propagation. The shoot or ‘scion’ is not directly rooted, but instead joined to a rootstock. The practice of grafting was developed, because a tree with beautiful and aromatic fruit does not necessarily grow well. A grafted tree consists of at least two different plants with qualities which complement each other. This makes it possible to combine the positive growing characteristics of the rootstock with the qualities of the cultivated fruit to create a tree which grows healthily and produces good fruit.

Rootstock

For grafting to be successful both partners must ‘get along’ with each other. This means that only certain plants can be used as a rootstock. These are mostly members of the same species, although related species can also sometimes be used. As previously mentioned, the rootstock generally determines the growing characteristics of the grafted plant. It also has an effect on characteristics such as the plant’s resistance to disease or frost. This means that for every variety of fruit there is a multitude of different rootstocks that can be chosen to match different criteria. Today, dwarf rootstocks are used for most fruit trees, because they keep the tree small and make it fruit earlier. An example of this would be the practice of grafting many pear varieties on quince as a rootstock, because it does not grow as vigorously and this slows down the growth of the pear. For my method of grafting, however, I prefer rootstocks from vigorous growing seedlings (from fruit grown from seeds) and wild varieties. Dwarf varieties used as rootstocks do not grow as vigorously. They do not develop strong root systems, which is one of the most important conditions for an independent tree. The weak roots mean that the trees frequently have to be tied to stakes so that they will not be knocked over by the wind or snow. They also cannot supply themselves as well with nutrients, which means that they have to rely on good soil or even fertiliser. They are more sensitive to drought and they are usually much more susceptible to disease and frost. For my requirements I need hardy and independent trees which can thrive on poor soil and in unfavourable locations. These needs are best fulfilled by rootstocks from vigorous and hardy seedlings. Their strong growth means that they will fruit a few years later and also grow taller, which makes harvesting the fruit a little more difficult. But I accept all of this happily.

Cherry trees in full bloom on the site of an old spruce forest.

On the one hand, dwarf rootstocks would not grow so well on the farm. On the other hand, the characteristics of these rootstocks and the cultivation they make possible would save me a great deal of work. If I take into consideration the amount of work I save in terms of maintenance by grafting onto vigorous rootstocks, the greater amount of work required to harvest them is put into perspective. A further point which speaks for using vigorous growing rootstocks is the fact that they live for much longer. So I can plant a fruit forest that will continue to provide food for the next generation.

Scion

You should use strong and sturdy perennial shoots for scions. Water sprouts are not suitable. The middle part of the shoot is used for grafting, which should have three to five buds on it. Scions should be cut during the dormant months in winter (January is best) and stored until they are grafted in the spring. It is best to store them in a cellar in wet sand. Scions can also be cut and used fresh for grafting. If you do this, it is best to use the shoots straight after they are cut. If I find a nice tree somewhere that I want to take a scion from and take home with me to enrich my orchard with, I have to stop the scion from drying out with a damp cloth. If the scions are cut in spring or summer, cut the leaves off and leave about 1cm on each leaf stalk.

Grafting

The aim of grafting is to bind the rootstock and the scion so that they grow together. It is necessary to achieve a good contact between the cambium layers of the rootstock and scion. The cambium is the cell layer between the bark and wood, which is responsible for growth by cell division. Only when these layers are well joined will the graft be successful. There are many different grafting techniques, which can be used on different parts of the tree and at different times. With a little skill and practice you can learn and carry out these techniques for yourself very easily. Neat work is particularly important. All cuts must be clean and you must not touch them, because this will contaminate the surface of the wound. For cutting you need a very sharp ‘budding knife’, which is only used for this purpose.

The author demonstrates the technique of cleft grafting.

• Whip and Tongue Grafting

For this method of grafting the rootstock and scion must be of the same thickness. I usually whip and tongue graft my young plants after the first or second year of growth in spring. I graft them at the root collar, which means that I cut the rootstock to around 10cm above the ground at an angle. The cut must be three to four centimetres long so that the rootstock and the scion make contact over a large area. It must be done in a single stroke, so that any unevenness is avoided. If the cut is not successful, it must be done all over again. I then cut a tongue in the rootstock (see the diagram ‘Whip and Tongue Grafting’). The scion is also cut at an angle and cut with a tongue to fit the one in the rootstock. It is important to ensure that there is a bud on the opposite side of the cut. Both cut areas must fit together flush so that the cambium layers join together properly. Now the scion is slotted into the rootstock. The graft is then wrapped with raffia. The buds must remain uncovered so that they can still sprout. This binding is to improve the contact between the rootstock and the scion. To stop the graft from drying out or getting infected, it and any open cuts are painted with grafting wax. The buds must naturally not be covered.

• Cleft Grafting

A cleft graft is used when the rootstock is thicker than the scion. There are many different types of cleft graft, but the simplest is the bark graft. I generally carry out this type of grafting in May when the bark can easily be peeled back. The method is very simple. The stem of the rootstock is cut straight at the desired height and most of the twigs are removed. When doing this remember to leave one or two small twigs as nurse branches. They are important for supplying nutrients and also help to prevent sap from building up in the tree. The surface of the cut is then neatened with a specialist knife called a pruning knife, because clean cuts heal faster. A slit is now made in the rootstock without damaging the cambium and the bark is peeled back. The slit should be around 4cm long. The scion is cut at an angle as before. This cut should also be 4cm long. Again there should be a bud on the opposite side to the cut. To help improve the success of a graft, I also smooth off the edges of the area around the cut slightly (by roughly 1mm). Be sure to only smooth off the bark and not the cambium when doing this. This technique uncovers more cambium, which in turn makes it easier for the scion and rootstock to grow together. Now I push the scion into the gap underneath the bark. The bud level with the cut on the scion should be around the middle of the graft. Finally, the graft is bound with raffia and all cuts are painted with grafting wax. The buds should again remain uncovered. Depending on the thickness of the rootstock additional scions can be grafted. If the rootstock has a diameter of roughly 4cm or more a second scion should definitely be used. If the graft is successful, the nurse branches can be removed the next year.

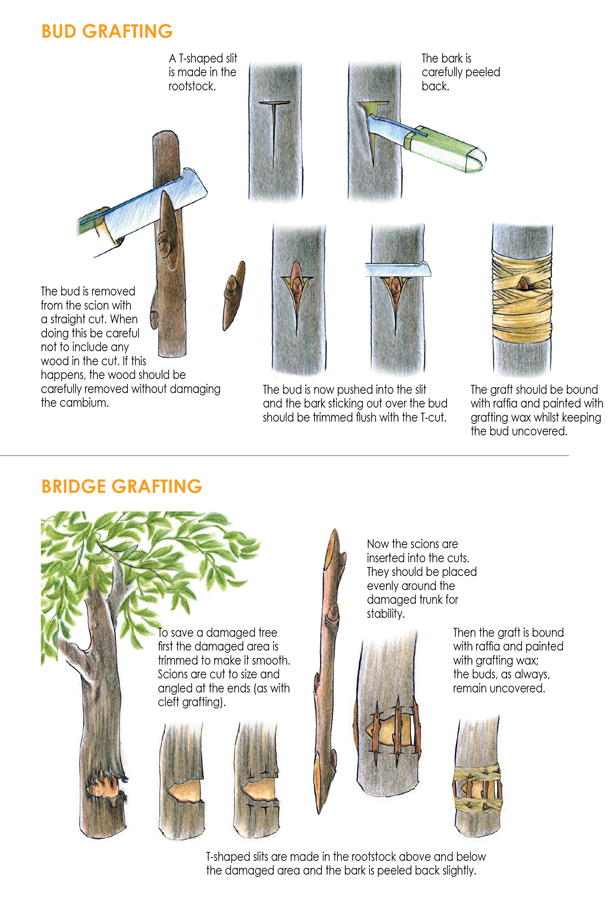

• Bud Grafting

Another method of grafting is bud grafting. In this case, only a single bud and not the entire scion is joined with the rootstock. A T-shaped cut is made in a smooth area of bark on the rootstock. Next the bark is peeled back slightly at the sides of the vertical cut. Then a well-grown bud is removed from a scion with a straight upward slice starting from the bottom (from the base in the direction of the tip of the shoot) in the shape of a shield. Be sure not to include any wood in the cut. Now insert the bud in the slit and push it in with the back of your knife. The bark overlapping the bud should be trimmed flush with the top of the T-shaped cut. Finally, the graft is bound with raffia and painted with grafting wax. The bud should remain uncovered.

You can use an active bud as well as a dormant one. An active bud should be budded in spring (May), and then it will sprout within the year. With a dormant bud you should bud in the summer (July or August). Dormant buds sprout the next year, hence their name. When grafting active buds you should use fresh scions. The leaves on these twigs are cut to short stalks. You will know whether the grafting has been successful if the leaf stalks fall off after around three weeks. Once the buds have joined with the rootstock properly and have sprouted, I cut the rootstock just above the graft and paint the cuts with grafting wax. When bud grafting it is also a good idea to use more than one bud. This increases the chance of success, because not every bud will necessarily sprout.

• Bridge Grafting

With the help of grafting I cannot only propagate fruit trees, but I can also save damaged trees. If a tree is heavily damaged, the flow of sap is interrupted or destroyed and the tree begins to dry out and die. If it survives, sooner or later the trunk will give way, because the damaged area begins to rot and the tree is destabilised. However, a tree in this situation can be saved relatively easily. I only have to join the area above and below with scions (preferably from the same tree), so that, in time, they can take over the transport and support functions for the trunk, in other words, the damaged area is bypassed. I begin by cleaning the wound and trimming all of the frayed areas. Now I graft scions above and below the wound underneath the bark. You should always use at least three scions.

This method can even help to save heavily damaged trees. Trees treated in this way are better protected from sources of damage (like browsing) in the future, because they are no longer easily accessible. The tree also has the resources to repair itself if it is damaged.

With grafting there are no limits to your fantasy: it is perfectly possible to graft a number of varieties onto a single tree. This is a great advantage when I only have space for one tree. As I have already mentioned, many fruit trees, especially apples and pears, cannot self-pollinate, so they must have pollinating varieties available. I can solve this problem by grafting on a branch from a pollinating variety. Having a number of varieties on one tree in a small garden helps to minimise the risk of crop failure. Different ripening times and different varieties of fruit make it possible not only to have a more varied harvest, but also creates a unique collection and increases the happiness gained from a single fruit tree. I believe that anything that is fun should be allowed in the garden. There are endless possibilities for experimentation. All you need is a little imagination.

In a fruit forest everyone is happy.

Sowing a Fruit Forest

Using seedlings as rootstocks for my fruit trees is a very simple, economical and practically risk-free method of cultivating a lush fruit forest or orchard. I will now describe this method in greater detail.

Fruit trees generally prefer high-quality soil. I begin by preparing the area using soil-improving plants, so that my fruit trees will thrive. The role of green manure in the creation of humus is covered in ‘Soil Fertility’. The amount of time this takes depends on the properties of the soil. The majority of acid soil on the Krameterhof, where spruce forests once grew, took around two years to improve to the point where I could grow fruit trees and other demanding plants without additional support. Green manure is not a one-off measure: it must play a continuous role in cultivation, because a fertile and healthy soil is the key to success. Once I have prepared the soil, it is necessary to loosen it for sowing.I graze my reliable workers, the pigs, there and they dig over and loosen the soil for me. This prepares the area for fruit trees and I can begin to sow the plants. The best and most economical source of seeds I have is in the form of pomace (the pulp left over from pressing fruit for juice or cider), although the material left over from the must when distilling schnapps will also work well if the seeds can be separated after they have been heated. I leave this pomace to ferment for around four to five weeks and distribute it over the area. During the fermentation process the layers which naturally delay germination are broken down. This stratification greatly increases the seeds’ chance for success. As the trees grow in their intended location from the start, they can best adapt themselves to the soil and climatic conditions. The diversity of plants lessens the chance of browsing from deer. Fencing the area off is never a bad idea, as this means it can also be used as a paddock. Once the trees have been growing for one to two years, they can be grafted. I only select the best trees for grafting, so I get the optimal plants for the location. Trees growing too close together can be replanted. This method is not only simple and economical, it is also particularly well suited to ‘unfavourable areas’, because my trees have had time to adjust to the local conditions from when they were seedlings. This method should also encourage you to experiment, because it requires very little effort and practically no risk. It would be simple to turn a spruce forest into a fruit forest using this technique. I do not graft all of the seedlings in the area, because they can also produce interesting fruit. I have often received very sweet fruit ideally suited to schnapps from cherry seedlings. There is a market for a great variety of kinds of wild fruit, as I have already mentioned, and they should therefore not be neglected. I also like to grow wild fruit in the form of fruit hedges, which can serve as windbreaks to protect more sensitive cultivated fruit trees. In this way they fulfil many different functions. The fact that the hedges provide an environment for large numbers of useful animals and insects is obviously also an advantage.

The rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) is not only a beautiful tree, but its fruit is highly sought after in the production of schnapps.

The ‘Shock Method’

As a child, my route to school was very long and exhausting and took about two hours even if I walked quickly. It was a simple cart path and went through the forest and past fields. I would find no end of interesting things there; a root or a nice pebble, and now and again a small tree which I would plant in my little garden. Shortly before the end of June, the end of school, I found a few small wild apple trees on a pile of stones on my way back home. I could not resist and took them back with me. Although they were a good two metres tall, I could simply pull them up without digging, because their roots had found little purchase on the stones. Full of joy, I carried them back home and wanted to show them to my mother before I planted them. Instead of the praise I had hoped for, she scolded me and said that it was a shame for the beautiful trees, because with fully-grown leaves they would not take root at this time of year. Despite this, I took the trees to my little garden (Beißwurmboanling), dug them in as well as I could and, as always, covered the soil with leaves. I could not water them, because the garden was too far away from the nearest source of water. I did not have any great hopes of the trees growing. My mother had explained to me that I was replanting the trees when it was already far too late and they were already in full leaf. For this reason, I came upon the naive idea of removing all of the leaves, because they seemed to be stopping the trees from taking root. Then they stood bare in my little garden. I went to look at them every day in the hope that I might see some sign of life. Several weeks passed until one of the trees suddenly, and to my complete surprise, produced new shoots. Once I discovered there was no stopping me and, pulling her by the apron, I brought my mother to look at the garden. She would not believe my story, so I had to bring her, so that she could see for herself. Even she was surprised and she asked me: “What did you do to make the trees grow? What luck!”

Fruit trees planted between raised beds using the ‘shock method’.

Later on this experience inspired me to develop my ‘shock method’. It is an emergency technique to allow badly rooted trees without root balls to be replanted, even when they are already fully in leaf, in flower, or bearing fruit. I begin by laying the trees in the sun, so that the leaves dry out. Naturally, the roots should be covered, because they cannot tolerate sun. I use a wet jute sack to cover the roots. To make sure the leaves dry quickly, the trees must not be watered. The wet sacks will ensure that the roots do not dry out, but they will not provide enough water to supply the leaves. After about a day, the leaves will have dried out and the trees can be replanted. I do not soak the soil before planting or water the trees afterwards. The only protection they receive is a layer of mulch to keep the soil moist. I would never be able to water all of the trees on the Krameterhof, because it would take far too much time and energy. Trees planted using my method quickly develop new, fibrous roots, which supply the trees with nutrients and water again. They can survive the initial lean period, because they no longer have any leaves or fruit to support. If I were to plant a tree in full leaf and fruit instead and not water it, then all of its energy would be used to maintain the leaves. The roots would not get enough attention and the tree would grow badly, if at all. This tree could be compared to a cut flower: it is given plenty of water, yet it can barely support itself. Trees treated using my ‘shock method’ concentrate on taking root and do not produce shoots until they have the energy to do so. The trees are raised to be independent.

I have cultivated thousands of trees over the years using this method. I have bought remainder stock, which are often just chopped up or burnt, from tree nurseries at a very good price and planted them using my ‘shock method’. In my experience, trees planted using this method grow best between raised beds. A large amount of moisture collects between the beds and the trees recover quickly.

After two to three years the trees have developed so well that I can dig around the root ball and replant or sell them. In this way my childhood experiences have provided me with a very good business.

Processing, Marketing and Selling

The diversity of an orchard provides a large range of processing and marketing opportunities. The dessert and cooking fruit is harvested and stored in a fruit or earth cellar. The fruit for juice, cider and vinegar as well as for making schnapps or for drying is sorted and processed. Fruit can also be made into jam or compote if there is a demand for it. Oil (from nuts) can also be pressed. As grafting and processing fruit takes a great deal of energy, the market situation should be carefully examined in advance. It is important to find out if there is a large enough market for the product and if you will get an adequate price for your efforts.

The success of your business also depends on the strength of its marketing. With a large farm like the Krameterhof, where we grow approximately 14,000 fruit trees of different varieties over an area of 45 hectares, it would be impossible to harvest all of the fruit we grow and process it. This is not only because the work required would be too extensive, but also because there are difficult-to-access areas, which make harvesting very difficult. In our case, the best use of these steep slopes is as a source of food for the pigs. The fruit trees grow just like any alder or spruce – the only difference is that every year they produce beautiful flowers and in autumn they yield fruit. They do not take any more or less time to maintain than any other tree. The fruit trees feed my livestock every year for a very long period of time without me having to do any work. Their flexibility is one further reason to try growing them.

Changing from commercial fruit growing to a permaculture system is really quite difficult. Usually commercial orchards are grafted on dwarf rootstocks and tied to espaliers. These dwarf rootstocks do not develop primary roots, because they no longer require them for support. A naturally growing tree on a seedling rootstock which is not supported by a stake naturally develops strong primary roots. It braces itself against the wind and develops into an independent tree that requires no further maintenance. In the espalier gardens of commercial fruit growing it is a good idea to make use of pigs. This means that you can leave all of the trees standing. They should no longer be fertilised or sprayed with pesticides and the yield should be used as a natural source of food for the pigs. For larger livestock like cattle and horses this is not advisable, because the many wires and narrow paths would present too many hazards. If the wires and stakes were removed, however, the orchard would be left in a sorry state. In this case, you must decide if you want to make a low-quality product, which for the most part will not be profitable. Changing to a permaculture system is not only difficult because of ‘addicted’ trees, but freeing yourself of the mind-set of commercial fruit growing also requires you to radically change the way you think.

Fruit greatly enriches the diet of people and animals.

Whilst I was providing a consultation on changing a farm over to using permaculture techniques in South Tyrol, an elderly farmer told me that he had been asked by the marketing cooperative to harvest his apples within a set period of time. When I replied that the apples would still be green, he explained that the apples had to be green, otherwise they would be discarded as cheap pressing apples. He was not happy with the rates: the farmer said that he had only just received the invoice for the previous year and had to pay money back, because the storage costs were higher than the proceeds. I was surprised and asked him why he was still harvesting apples and delivering them. “Well, yes,” he said, “but maybe things will go better this year.” I told him that if I were him I would think of alternatives. “No, we can’t do that here, we have contracts and we can’t just get out of them. Also, what would people say?” Once he had admitted that he was making a loss and all that he was left with was work and the expense of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, he said, “Well, there’s nothing you can do about that, that’s just the way farming is. I can’t do anything about it, you should explain that to my son.”

We need creativity and courage to forge new paths. There are many ways to be a successful farmer. The higher yield of intensive farming, as the example shows, is no longer a guarantee of profitability – quite the contrary. The larger amount of work and the financial aid required often eat up the profits. How long will it take for farmers to free themselves of the shackles of cooperatives and make their way to independence?