5 Gardens

Kitchen Gardens

The nicest areas around houses were once reserved for kitchen gardens. There, farmers cultivated valuable fruit, vegetables and medicinal and culinary herbs, which meant that they were available right on the doorstep. The purpose of a kitchen garden was not only to grow food; it also served as a pharmacy just outside the house, which was very important for the health of the family. Even as young children we came to see the garden as an important part of our lives. We watched our parents as they worked and we could experience the way the many colourful, sweet-smelling and delicious plants grew.

I can still remember the joy I felt when I pulled up my first baby carrots and radishes in the garden. My mother scolded me, because the vegetables were too small to be harvested, but I simply could not resist. They tasted so good that I pilfered a few from the garden every now and then anyway. As children we were always happy gardening, because there was so much to see: all manner of insects, from earwigs and ladybirds to bumble bees and butterflies could be found there. The garden was full of buzzing creatures flying around, the plants smelt wonderful and we could always find something to eat. We found it so interesting that we always went there in the hope of discovering something new. In hindsight, the most important thing was that we, in a manner of speaking, grew up around the plants and that we could experience the way everything lived and thrived for ourselves. The days were usually too short and it was often dark before we had finished investigating the garden. On these expeditions through our Gachtl, which is what gardens are called in Lungau, we also learned how each of the plants were cultivated and where they grew best. We grew up with nature around us and we learnt through play. We could see the way that everything grew, flowered and smelt so wonderfully and also the way it could be prepared into good food. They were gardens for the heart and soul and for the health and well-being of the whole family. These days a kitchen garden like that is usually described as a ‘therapeutic garden’. As a result of increasing mechanisation, many farmers turn the areas around their farmhouses into parking places and garages or they build roads around them. By the 50s and 60s this tendency had developed to such an extent that many farmers were even ripping out their old grain silos and existing storage buildings. Old bread baking ovens, which were once built outside, gave way to asphalt parking places. Sadly, many kitchen gardens also disappeared. Very few people were willing to take on any of the work involved in keeping a garden of their own. Fortunately, people are now beginning to think differently. Many people are once more becoming aware of the fact that the quality and flavour of home grown organic produce is far superior to the food bought from a supermarket.

The garden was right by the wall on the east side of the Krameterhof.

In these fast-paced times when so many people anxiously rush their way through life, more and more will discover gardening to be a relaxing balance to their working lives. For many people their own small garden is their only opportunity to come into direct contact with nature. Happily, medicinal and culinary herbs are also returning to the garden. The healing properties of many medicinal plants have been scientifically proven and are used in modern complementary medicine. This development within the last few years gives me the hope that even more people will soon take an interest in nature and feel a part of it again, instead of believing that they can control it. Creating your own garden is exactly the right way to begin.

Memories of our Gachtl

Our Gachtl directly bordered the eastern side of the house, where it remains to this day. It was enclosed with a picket fence and had a variety of fruit bushes. I remember the redcurrants, blackcurrants and white currants by the fence and the strawberries that reached all the way to the wall of the house. A gooseberry bush and an intensely sweet-smelling double-flowered rose bush grew in the sunniest part of the garden. This was the best place for them, because these bushes are very susceptible to mildew; the reasoning being that damp, which lasts longer in the shade, encourages mildew. In the dry and stony places we grew thyme, lavender and sage. In the nutrient-rich places we planted mint, lemon balm, sun bonnet, motherwort and lovage, all of which can also cope with light shade. Between these herbs grew poisonous medicinal herbs like monkshood and foxgloves, which catch the eye with their very beautiful flowers. Our mother told us again and again: “You must not touch or eat these herbs, they are poisonous”. Poisonous plants are rarely found in gardens today. Possibly because people are afraid that, if left unattended, children might eat them and poison themselves. When I was older, I discovered through my various experiments that poisonous plants play an important role in the interactions within nature. Now I am convinced that they make a significant contribution to a healthy soil life. A varied diet is, in my opinion, incredibly important for the development of soil organisms. After all, an earthworm cannot go to see a vet. The normal and medicinal plants available to animals – however small they might be – should be as diverse as possible. I also think it is very important for children to learn something about the medicinal and poisonous properties of plants, the things that they hear and learn makes an impression on them and influences the way they deal with nature in later life.

To the left and right of the garden gate grew the edible plants that my mother used the most: lovage, chives, leeks, onions and garlic. They were planted here so that they were very quick to reach, as she did not have much time to cook. Naturally, she had to work in the fields and with the livestock too. She would frequently pass the job of quickly going into the garden to collect chives or other herbs to us children – the soup was often already on the table and everyone had arrived to eat.

Lovage (Levisticum officinale) thrives in partial shade and in deep soils. A single plant will cover the needs of a family of four. This popular medicinal and culinary herb hinders the growth of neighbouring plants and spreads vigorously, so it is best to plant it alone in its own corner of the garden.

On the sunny side of the garden were beds for vegetables like beans or peas. If the soil was warm enough, we planted the runner beans in the middle of May because of the altitude (the garden in the Krameterhof is 1,300m above sea level). Mother planted lettuce between them to protect the beans, because they are sensitive to the cold. Lettuce does not present any competition to beans. As a catch crop radishes and carrots are also very suitable. In the other sunny and nutrient-rich beds we grew kohlrabi, cabbages, turnips, radishes and broccoli. Salad plants could always be found as a catch crop: butterhead lettuce, iceberg lettuce, loose-leaf lettuce and endive. However, my mother always kept parsley away from the salad plants: “It doesn’t go with the rest,” she said.

By the wall of the house stood a damson seedling (Prunus domestica subsp. insititia), which we did not prune. The fruit was ungrafted, which means that the suckers went on to grow into new trees that produce the same fruit as the parent tree. The quality of this fruit was excellent, it was very aromatic and ripened from the end of September to the beginning of October.

Various types of lettuce provide a fresh source of vitamins from spring to winter.

Lemon thyme (Thymus citriodorus) develops an intense flavour in dry, stony or sandy areas.

The areas around the fence and in the garden (sunny, shady, dry or wet soils) were given to the plants that were suited to them. This is, without doubt, the recipe for success in any garden, because plants that are in the right places will thrive and are not as susceptible to disease. They also develop the highest nutrient content (essential oils, bitter substances) in the locations that they are naturally suited to. For instance, if you plant thyme appropriately to its natural environment in a warm, dry place (sandy or stony), then naturally it will not grow as high as it would on good garden soil, but it will develop a more intense flavour, which means that its nutrient content will increase. Although thyme cultivated on good garden soil will grow up to 30cm high, it will grow spindly and will have little flavour. The spindly thyme will also not possess the healing properties that many people expect from it. Next to the thyme we grew both sage and lavender. It was certainly an impressive array of scents for such a small area!

The Pharmacy on the Doorstep

The wide selection of medicinal herbs turned kitchen gardens into an indispensable source of valuable medicines for every farm. This was useful, because doctors and midwives were often difficult to reach and also took a long time to arrive. Farmers tended to ask themselves very carefully if they needed a doctor at all, because they could not easily afford this ‘luxury’. So in every kitchen garden there was an even mixture of medicinal herbs that might be needed. Every farmer had their own recipes for medicinal creams, tinctures, compresses, poultices and teas. The farmers passed these recipes down through the generations, mainly within the family, and they constantly improved them. This is why remedies vary so much from farm to farm. If people with specific ailments lived on the farm – such as those in need of permanent care – then the farmers would take these particular needs into account when choosing the medicinal herbs.

If someone in our family fell ill, the first thing my mother did, was to go into the garden. For every ailment she knew a herb, which she used in various different ways. She made a tea from mint, lemon balm and marsh mallow and coughs would disappear. Since then the soothing effect of marsh mallow (Althaea officinalis) on sore throats, hoarseness and dry coughs has been thoroughly investigated and scientifically recognised.

The herbs were not only used for acute complaints and as medicine, they were also used for cooking. My mother used more or fewer medicinal herbs (lovage, thyme, garlic etc.) according to taste and the health of the family, in a variety of dishes. Many of these herbs are only known as culinary herbs today. These plants, which are mostly used these days without realising, are very important medicinal herbs. Lovage, for instance, encourages the appetite, stimulates digestion and has a diuretic effect. When thyme is freshly cut it has an antibacterial effect and its ability to regulate means that it makes dishes, especially meat and sausage based ones, easier to digest. Perhaps this is why the flavour of thyme complements these dishes so well? Freshly cut garlic has antibacterial and antifungal properties. Eating garlic regularly can even lower cholesterol levels. Finally, it is also an excellent medicinal plant for preventing thrombosis, because it helps to prevent blood clots. The antifungal properties of garlic can also help to protect plants: garlic tea (brew a few cloves of crushed garlic for a short period of time and leave them for a day) can be very effective against all kinds of fungal diseases (e.g. mildew), and lice are discouraged by the pungent smell.

Medicinal herbs were also used to treat sick livestock on farms. For instance, the farmers on practically every farm made their own calendula cream. It alleviates every kind of injury by encouraging wounds to heal and bringing down inflammation. The farmers often successfully used it to treat udder inflammation. Calendula was made into a tea and then used to clean wounds. Since then I have found that calendula also has a beneficial effect on the soil: the plants secrete substances from their roots which discourage nematodes, which (when there are large numbers) can be very harmful to crops plants. For this reason I continue to sow these effective and also beautiful medicinal plants in different areas – preferably on deep, wet soil – and collect the curled seeds in autumn for sowing the following year.

Valerian is another example. Its relaxing properties are well known. Valerian tea was used in veterinary medicine for the treatment of colic and cramps. Cats are an exception to this, because they react very sensitively to valerian. Also chamomile, which is calming and works against cramps and flatulence, does not only help people with digestive problems, but also horses, dogs and chickens.

Many medicinal herbs that were used grew outside the garden on the edges of paths and fields and on slopes. Mugwort, mullein, comfrey, greater celandine, stinging nettles, lady’s mantle, coltsfoot, dandelions, tormentil, cranesbill and chicory are just a few examples.

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) is not only wonderful to look at, but it is also a medicinal plant of considerable value. It strengthens the immune system and is therefore used for colds and to heal wounds.

Because of their inconspicuous appearance they are not seen to be what they are: something special. Now their medicinal properties have been almost forgotten!

Preparations made from medicinal and wild herbs were still widespread in the 40s and 50s. In the following years fast-acting and at first glance effective tablets began to be accepted on even the remote farms and they replaced medicinal herbs. Fortunately – after many people have had to struggle with the side-effects of medication and some have had to take tablets in order to overcome the side-effects of other tablets – we are now beginning to remember this old knowledge, which has been handed down for generations. Unfortunately, over the years many recipes have been irrevocably lost. When I was growing up I got to know many practitioners of natural medicine. When we children had a cough or stomach pains my mother often collected poultices and salves from our grandmother, who lived in Sauerfeld near Tamsweg. A poultice is a mixture made of natural products that is spread on baking paper (or similar) and placed on the chest or back of the person who is ill. The ‘montana salve’ was particularly effective. It was used to quickly alleviate whooping cough and colds. The farmers made it from the flower petals of different medicinal herbs, of which the peony or ‘montana rose’ (red flowered) made up the greatest part. This salve had such an intense and pleasant scent that we children never resisted when we were smeared with it or had it applied as a poultice. However, we behaved very differently to another very effective method: applying roasted onion slices, garlic and horseradish. We made this with lard and applied it with hot cloths. The medicinal properties of these methods were astonishing.

Many farmers also made drawing salves. To make this they used tree resin, in other words, liquid larch pitch. They mixed this with different medicinal herbs and made it into a poultice. I remember that the effect of the drawing salve was often so intense that the paper had to be removed, because the sensation became unbearable. The effect was so powerful that it could treat inflammation and festering wounds in a very short time.

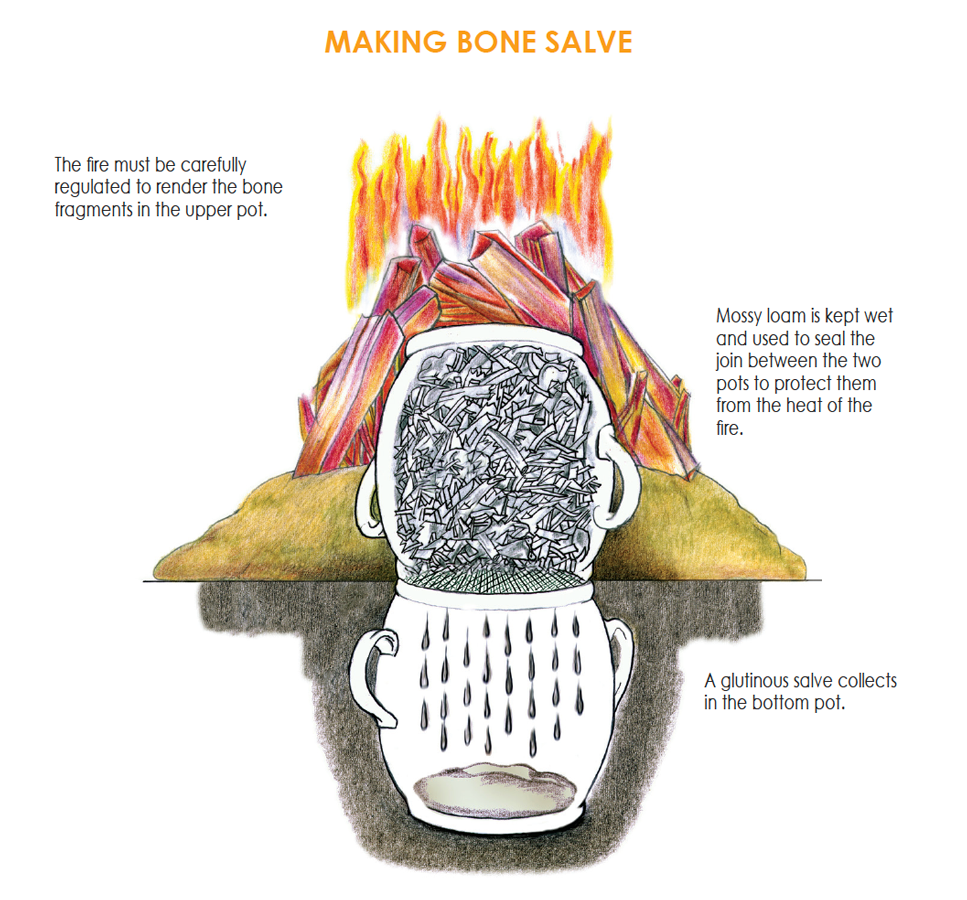

Finally, the farmers also made a bone salve from actual bones. For this they saved the bones from cattle and pigs throughout the year in a specially prepared chest. In the chest there was a ventilation grate to allow plenty of air to circulate so the bones could dry out; this grate kept the chest from being invaded by mice. The bones were smoked, because for storage reasons most meat was smoked. In late autumn the bone salve man (Beinsalbenbrennermandl, literally ‘bone salve burning man’) came. This was usually a retired farmer, a woodcutter or herdsman who earned a few schillings as additional income for his autumn years by making bone salve. We children were always happy when this man arrived, because he told us so many stories from his life. We helped to crush the bones so that they would fit into the cast iron pots. Two ten-litre cast iron pots were used. The crushed bones were put in one of these pots and a wire grate was placed on top. In the second pot, which was the same size, we emptied a mug of water (a quarter of a litre). We buried this pot in the wet, mossy soil at a distance from the house. The pot was flush with the soil and upright. We placed the first pot with the bones inside it upside down with the grate facing down, on top of the second one, which was buried in the ground. The grate was only there to keep the bones in. We sealed the space around the two pots with clay and wet earth. Then the Brennermandl (‘burning man’) laid wood over the covered pots and started a fire. Experience was needed to do this, because there could not be too much or too little heat: it had to be exactly right. Naturally, we children wanted to put more wood on the fire to make it as big as possible. If we tried this he would rap us on the finger with a piece of firewood and tell us why we were not allowed. As I have already mentioned, a specific temperature had to be maintained for the fat to be drained from the bones and for it not to be burnt by too much heat. It required great care to ensure that the seal stayed intact and wet. If it were to become damaged, sparks could have reached the steaming oil inside the pots and caused an explosion. At the end of the process, there would be a glutinous brown mass in the bottom pot and in the top pot only light grey flakes of used up bone.

We used this bone salve to treat wounded livestock. The men who came to castrate the pigs, for instance, usually had a salve of this kind. Because of the pungent smell, which is similar to mineral naphtha or wood tar, it was rarely used on people. During the summer we spread a watered down form of it on the draught animals with a rag at haymaking and harvest times, to protect them from flies and horseflies. This provided the animals with very good protection, so that our work could be carried out without interruption.

Through experimentation I have discovered further possible uses for this product, e.g. as a deterrent against bark stripping in forest cultures, or to protect fruit trees from being gnawed by rodents. This remedy provides excellent protection for many years. The bone salve can be mixed with linseed oil, fresh cow dung, slaked lime and very fine quartz sand until it is of a paintable consistency.

You can still make this salve for yourself, but you will need to obtain the requisite bones from a slaughterhouse. These must be placed on a grill and smoked. (We used smoked bones, because we smoked most of the meat to make it last longer. Naturally, we did not have fridges and freezers back then.) Whether the salve would be as effective medically with unsmoked bones, I cannot say. We used the rest of the burnt bones in the garden as fertiliser.

I would now like to describe a few very simple recipes for remedies, which can be also be made by people with small gardens without any great difficulty. There was a time when these remedies could be found in almost every ‘home pharmacy’. As the potency of medicinal plants can vary from place to place, the recipes should be adapted. With a little experience the correct strength can easily be determined.

Calendula Salve

When making this salve the whole plant including the stem, leaves and flowers is used. First, two heaped double handfuls of calendula (Calendula officinalis) are cut finely. Heat roughly half a litre of lard (available from a butcher) and carefully fry the calendula whilst keeping it moving. Other fats or vegetable oils can also be used (e.g. olive oil). The mixture is covered and left to stand for a day. Then it is lightly warmed, filtered through a cloth and poured into a container. If you make it with vegetable oil, you must first incorporate a thickening agent such as beeswax. For one litre of oil you should use between 200g and 250g wax, which has already been warmed and melted. Mix the melted wax into the filtered calendula oil well, and then leave it to cool. The more wax you use, the stiffer the salve will be; so, if you prefer a very creamy salve you should use less wax. Calendula salve can be used to treat all kinds of injuries, because it encourages wounds to heal and keeps inflammation down.

Sage (Salvia officinalis) just before flowering. Its nutrient content is greatest when it grows in a sunny place and without fertiliser. Sage tea is a well-established remedy for a sore mouth or throat and helps with digestion problems.

Lemon Thyme and Thyme Oil

Sprigs of thyme should be picked during dry weather at midday, because that is when the scent is most intense. They should then be placed in a bottle with cold pressed sunflower or olive oil. The oil should be about two fingers above the sprigs of thyme. The bottle is now left in a sunny place such as a windowsill for 14 days. Then the flowers are sieved out with a cloth. To make the oil more potent, the process can be repeated with new flowers. The oil should only be used on children with caution. Keep an eye out for possible reactions on sensitive skin. This old remedy is recommended for sprains and rheumatism; it should be rubbed in regularly to the affected area. It is also recommended for people who have suffered strokes.

Chicory Tea for Diabetics

Steep equal amounts of chicory root (Cichorium intybus), dandelion root, stinging nettles, French lilac and bilberry leaves in hot water. For three tablespoons of the plants you will need one litre of water. The tea should only brew for a short period of time and can be taken every day. Chicory was once used by diabetics. The farmers also used to make fresh juice from it, only a teaspoonful of which was taken to lower blood sugar levels.

Tormentil

A powder can be made from dried tormentil roots (Potentilla erecta) and stored in a jar. They can, for instance, be ground up in a coffee mill; the finer the powder the better. As a result of its ability to stop bleeding, it is used to treat heavily bleeding wounds. The powder is used directly. The wounds heal very well without leaving large scars.

Vegetable Patch

In addition to a kitchen garden, many farmers also had a large vegetable patch that was fenced off and, like the garden, was replanted each year. In the vegetable patch we grew white cabbage, which was used to make sauerkraut, and provided us with the vitamins we needed in winter. Farmers also planted turnips, chard, beetroot, swede, stock feed carrots and black radish. Turnips, chard and stock feed carrots were used to feed the cattle. We could hardly wait until mother finally put the first Krautspeck (bacon cooked and smoked with sauerkraut) on the table. The whole house and surrounding area smelled of freshly cooked Krautspeck and sauerkraut. When the postman came to the door he would cry loudly, “Ah, it’s Krautspeck today!” Naturally, mother could do nothing less than to invite him to have a good portion.

The Most Important Work in Our Gachtl

When I was a child, we always broke up the soil in the garden in spring. This was particularly tiring work for us. Afterwards, we divided up the beds with straight paths. We then positioned the young plants in these beds. The plants had to be planted early to give them a head start in harsh Lungau. They could also go in a container on the windowsill or in a cold frame to start them off.

A cold frame consists of a simple wooden box that is covered with a window or clear sheeting. In the spring, we would place a 30-cm-thick layer of straw and dung at the bottom of the cold frame and cover it with garden soil. The dung warms up through the process of decomposition and functions like underfloor heating for the bed. The cover of glass or sheeting has the same effect as a greenhouse. When creating a bed like this, you should choose a location that is sheltered from the wind and as sunny as possible, in order to make the best use of the spring sun. The plants selected must, of course, be made hardier before they are planted out. Doing this in stages is particularly important so that any damage to the plants’ growth is avoided. The plants must get used to the harsh temperatures outside gradually. The easiest way to harden the plants up is by increasing the periods of time the cover is removed. Towards the end of the process, the cover can even be left open by a crack overnight. My mother would begin to harden off the first plants around Saint Joseph’s Day (19th March). As soon as the plants were large enough and the overnight frosts were over, she planted them out in the garden. She pushed dry branches into the soil for the peas and beans to climb. She maintained the garden borders, where different bushes, medicinal herbs and flowering shrubs grew. She removed dead flowers and stems, spreading them over the soil around the plants. She then covered the material with a few spades’ worth of soil. From time to time, she thinned out the plants by digging up those that were growing too close together and either planting them elsewhere or giving them to the neighbours.

Our garden was very large and the vegetable patch was even larger, which naturally made it a great deal of work. As my mother could not look after the vegetable patch on her own, us children had to help with the raking and weeding. Raking was certainly not our favourite job, although I enjoyed weeding. Sometimes mother would just pull up the larger ‘weeds’ and leave them amongst the plants – usually on a sunny day so that the roots dried out quickly. In this respect, my small garden was somewhat untidier than my mother would have liked, which made her wonder how everything grew on my dry Beißwurmboanling (a steep and stony slope, a Boanling is the edge of a meadow). She said that she could save a great deal of work with my method, because the plants would grow just as well or even better, but she could not use it, because the neighbours and her friends would say that the garden was ‘untidy’. So we raked and weeded it industriously.

In autumn we harvested the winter vegetables. We pulled them up and put them into piles. Then we took a wooden chair and a chopping block to use as a work surface. We cut off the roots and leaves with a knife. This was done carefully, because the crops must not be damaged, otherwise they would start to rot in the cellar. The storage cellar was a frost-free earth cellar under the house. It was separated into rooms with larch posts. Each crop, such as potatoes, turnips or chard, went in a different room.

In autumn the cabbages went into the large fermentation barrel in the cellar – a large wooden barrel which was sunk into the earth. On the front wall of the cellar was a large pile of sand. We placed the best cabbages from the garden, complete with their roots, in here. We obtained the seeds for the next year from these plants. On special occasions, such as Christmas, we would cook one of the heads of cabbage.

We were very happy when there was a fresh cabbage salad with the Christmas roast (usually pork, prepared in the oven with potatoes and flavoured with garlic, caraway, thyme and marjoram). When we came back from church we could smell the roast some metres away before we reached the house and we would run happily into the kitchen shouting, “We’re having roast today!” Having this roast and fresh cabbage salad was very unusual back then; there were no fridges or freezers, and people certainly did not have meat every day.

After the cabbages were removed, the stalks would begin to sprout again They would turn completely yellow from the lack of light in the cellar. As children, although we were strictly forbidden, we always wanted to get hold of them because they were so delicious. Mother needed the roots and stalks for replanting the garden in spring. From the roots and stalks strong shoots would grow, which then grew flowers and seeds. Once the seeds had ripened mother cut the whole plant including the stem, put it in a bag and hung it up in the loft. This way the seeds could ripen and dry out. When the pods opened, the seeds would collect in the bag. All she had to do to sow the plants in spring was to beat the bag a few times against a tree or rock. The rest of the seeds would fall out and then she removed the dry stems. As well as salad and vegetables, the garden provided us with many medicinal herbs, which we used fresh or we dried or pickled them for winter. We also preserved fruit and berries: we dried them, made jam, juice, and schnapps from them or put them in vinegar. Then, as previously mentioned, we harvested and dried the seeds in the garden. We dried the strawflowers for floral arrangements throughout the year, for instance for church festivities. In winter there were few opportunities to get fresh flowers. We were also very careful with our money. So we made full use of the garden; and apart from the tools for working it, we did not have to buy anything. Seeds, young plants, dung and liquid fertiliser were already on the farm, we did not need anything else.

Although I want to preserve and reintroduce old farming techniques, not all the ones that we used were actually necessary. Today I maintain the garden with much less effort. My childlike methods of dealing with unwanted plants have found their place in the main garden. I make sure that none of the soil is left bare. I achieve this with mulch, by weeding and then leaving the ‘weeds’ on the soil as well as ensuring full plant cover.

I control rival plants and keep the soil moist with mulch and full plant cover. This means that I do not have to water the plants or do any weeding. Fresh material should not be applied too thickly. The mulch layer that can be seen here is being spread out.

My work in the garden is limited to lightly and carefully working and loosening the soil in the spring and repairing raised beds when required. It is not necessary to dig over the soil to introduce manure, because a nutrient-rich layer of humus develops from the plants that have been pulled up and left. Digging soil over is a particularly bad idea in autumn, because it leaves the loosened soil unprotected against winter frosts. This means that the soil life will not have the necessary protection, so it must either leave or freeze to death. However, I try to protect the soil from the frosts in winter, so I leave the plant cover in place. This protection provides as much warmth for the soil and soil life in winter as a winter coat does for me. Also, the soil does not freeze as quickly, which means that my ‘helpers’ can work for longer. In nature this works in exactly the same way. In autumn the trees shed their leaves and they collect on the ground like a blanket. Even if the leaves fell for another reason at first, I am convinced that this protective effect of nature is intentional and important. In addition, the biomass remains where it has fallen and turns into valuable humus there, exactly where it is needed.

I think that the familiar method of digging soil over to introduce manure is a bad idea, because cow dung does not work its way 30cm under the ground in nature. Dung always belongs on the surface where there is more air and there are plenty of organisms. Only there can it be properly converted into valuable humus by the soil life. If I introduce manure, I place at most one spade’s worth of soil over it, or cover it with a little mulch. There is often too much time invested in working in the garden. So the backaches suffered by those who like digging soil over, should cause them to stop and think. Too much work in the garden does not always bring the success that people hope for and it is not good for their health.

Today a fair degree of ‘untidiness’ prevails in my garden. However, the soil is covered by lush vegetation and is therefore protected from drying out and from the effects of the weather. The soil life is happy and productive.

I do not think watering is necessary in the garden either; except during extremely dry weather. With permanent plant cover or mulch, the soil can be protected from drying out. This saves me not only having to water anything, but it also gives me an independent system with independent plants. Excess watering also washes away nutrients, which makes additional manure necessary. We need to escape from this vicious circle and, especially in gardens; we need to free ourselves of this obsession with tidiness, because bare areas of soil are left defenceless against environmental effects.

Natural Fertiliser

Alternative Composting Methods

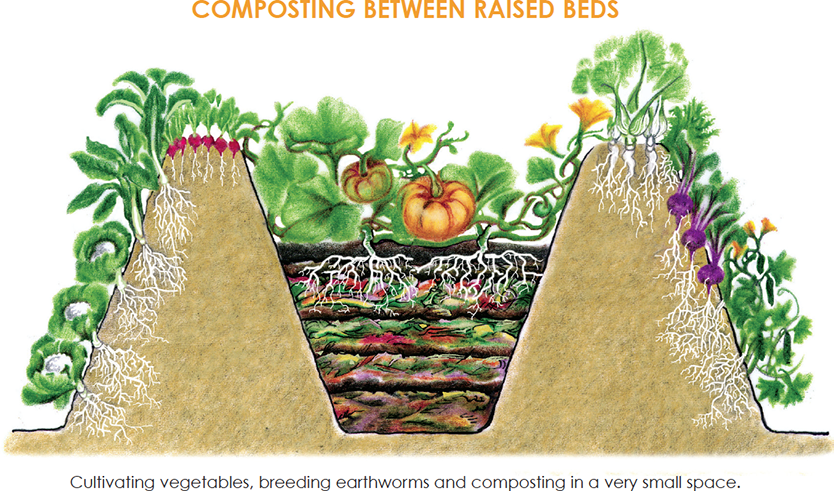

Composting is a way of producing high-quality fertiliser from organic waste. It is by no means necessary for a high-yield garden to have a compost heap. Mulching throughout the year and the skilful use of polycultures mean that additional organic fertiliser is not necessary. However, anyone who wants to compost anyway, can easily create an unconventional and easy-to-maintain compost heap. To do this, two raised beds running parallel to each other should be positioned so closely to each other that you can only just walk between them. The beds should be built at as steep an angle as possible whilst still holding together (60 to 70 degrees). Organic waste is left between the two beds each day. Each time you do this, cover the waste with a spade’s worth of earth, straw, leaves or similar material. Gradually, the organic material will come up to 60 percent of the height of the raised beds. The top layer should be covered with earth and planted or sown with vigorous growing vegetables (pumpkins, cucumbers, turnips etc.). Start at the furthest end of the bed and keep going until the gap is filled up. The best situation is when the dimensions of the compost heap ensure that the gap can be filled and will rot down within a year. The next year you can begin on the opposite side and throw the high-quality compost that was made the previous year on the beds to the left and right with a spade. As many earthworms will be living in there, you should be careful when digging. Afterwards, you can walk through the furrow that is left or climb over one of the raised beds to the side. Planks or large stones can be used to walk on. Using this method you can cultivate vegetables and compost and breed earthworms in a very small space.

Strong and healthy plants – even without using manure.

Any conceivable type of material can be used for composting: grass clippings, chipped material, leaves, hay, straw, algae or mud from a pond, kitchen waste, cardboard etc. – any organic material that decomposes is suitable. The smaller the material and the more active the soil life is, the faster the compost will become humus. The space between the raised beds is protected from drying out and retains heat, which helps the decomposition process. The plants growing on the raised beds should be chosen so that the compost still gets enough light, but is also protected from the sun. In partial shade the optimal conditions for the decomposition process develop and the compost quickly turns into the highest quality manure.

Mulch

Mulching also supplies the soil with valuable nutrients. It is nothing other than surface composting; it involves spreading a layer of organic material over the soil to serve as ground cover. The soil receives a protective cover from this, which prevents it from drying out, becoming eroded or suffering from the extreme effects of weather. Leaves, straw, cardboard and plants that have been pulled up whilst weeding are well suited to this. Green manure plants (clover, lupins and mustard) are particularly good. In the mulch layer a constant process of decomposition takes place, through which the mulch is turned into high quality fertiliser. For the material to rot down oxygen is required and the soil also needs it to ‘breathe’. When mulching you should also make sure that the material is spread as loosely as possible. If the soil pores become saturated the soil life will suffer.

A loosely spread layer of mulch protects my vegetable plants in the rock garden.

The thickness of the mulch layer depends on the material that I use. I only spread moist or wet material thinly, so that it can rot down slowly and will not begin to moulder. Dry material (such as straw or hay), on the other hand, can be spread much more thickly (20cm or more), because it is looser and has better air circulation. Naturally, it must not be packed down tightly. In addition, dry material does not compact as much as other kinds of biomass, when it rains. In contrast to expert opinion, I do not think that mulch material should be shredded. Experts are probably of this opinion, because the material will rot down more quickly, can work as fertiliser and also is easier to spread around plants. I do not shred the material, because I think it is better that the nutrients are released slowly and that the mulch layer is less likely to compact.

Working with mulch is really very simple: in spring you only need to scoop the mulch a little to the side and you can then sow or plant again. The areas where you sow and plant remain free of rival plants, while the other areas are still protected by mulch. This way unwanted plants can be prevented from growing, while those that have been sown or planted can develop unhindered. With a good mulch cover there is hardly anything left to weed. If you mulch all year round, you must regularly introduce new material. In accordance with the principle of mixed cultures, it is important to vary the plants and materials you use for mulching, otherwise plants will only receive the same nutrients. Variety keeps the soil and plants healthy. As with compost heaps, there are a great number of creatures that live underneath mulch – among them the much-loved earthworm. This is one of the reasons that once you have been mulching an area for a while, digging over or loosening the soil in spring will not be necessary. Mulch is also very effective under shrubs, trees and hedges, which is not surprising, because it mirrors what happens in nature already. It was people who first decided that leaves under trees were ‘untidy’ or ‘unattractive’.

Liquid Fertiliser

When I was young, the farmers understood the effect and preparation of liquid fertiliser well. Depending on the effect they wanted and which plants were available, they prepared different mixtures. In this way everyone developed their own ‘recipe’. With the appearance of chemical fertilisers and synthetic pesticides, the knowledge of how to use liquid fertiliser has died out in many places. Instead of this many people learn how to spray and fertilise ‘correctly’ without poisoning themselves. The long-term damage that is caused to our environment by the use of pesticides and chemical fertilisers is not obvious to the majority of people. Unfortunately, many people are willing to accept a short-term increase in yield using these methods. Anyone who wants to treat nature responsibly should say goodbye to the use of chemicals in fields and in gardens. Nature provides plenty of plants that, as a result of the substances they are composed of, are well suited to the production of effective plant feed and liquid fertilisers. To make some plant feed you need to place either freshly cut or dried plants in cold water for one day. Then the feed can be sprayed on your plants. The effect of this can vary greatly. Plant feed made from stinging nettles is particularly popular and can be used universally: the large amounts of nitrogen gives it the effect of good fertiliser and it strengthens the plants. Plant feeds of this kind can be very helpful with vigorous growing vegetables like courgettes, cucumbers and cabbage, however they should not be used with plants with low nutrient requirements like peas and beans, because of the danger of overfertilising. Plant feed made from fresh stinging nettle is also very good against aphids. The aphids seem not to like the smell and the burning effect of the nettle’s poison that is retained by the fresh feed is an additional factor. I think that it makes more sense to make cold water plant feed rather than tea, because tea needs to be boiled, which requires a large amount of energy, especially if you want to produce large amounts. I consider boiling unnecessary. If I need stronger plant feed, then I can just leave the plants in the water for longer and stir it regularly. The feed will begin to ferment and turn into liquid fertiliser. Liquid fertilisers are so rich in nutrients that they should always be diluted before they are used. They have – just like cold water plant feed – a good fertilising effect, they strengthen the plants and, therefore, also work naturally to prevent plant diseases, stunted growth and even the prevalence of a single organism. Strong and healthy plants are more resistant to disease; also insects usually prefer weakened plants. These natural plant-based pesticides are very easy to make at home and cost nothing! It is really quite surprising that they have faded into the background so much.

My Method

It is best if locally growing plants are used. It makes no sense to bring plants from a long way away or to import products for this purpose, even if it is recommended in specialist journals. Almost all plants are suitable for making liquid fertiliser. Roots, stems and leaves should only be left in a container long enough for the nutrients to be released, and the liquid fertiliser will develop from these nutrients.

A well on the doorstep: running spring water is practically a luxury today!

The production of liquid fertiliser for regulating pests must be observed closely over a long period of time. For my plant feed and liquid fertilisers I select plants with that contain certain substances – such as essential oils, bitter substances and poisons. When choosing the plants, I am guided by the instincts and experiences that I have accumulated over the years. Therefore, I continue to try new plants and mixtures, because there is still so much to experiment with and learn about in this area. If I have not used a plant mixture before, I start by making a test tea. For plant feed I use fresh spring water. Tap water is usually artificially processed and sterilised. Also filtration, irradiation, and chlorination can be necessary to comply with drinking water regulations. This water is ‘dead’ and no longer has any value for me as drinking water. I am, of course, very used to the fresh springs on our farm and I always avoid drinking the water when I come into the vicinity of a town. The taste alone horrifies me. If you have drunk this water for long enough, you probably no longer notice the taste. This works in a similar way to the taste of ripe strawberries and tomatoes that have not been sprayed with pesticides, which people often do not notice any more. If there is no spring water available, you can also use collected rainwater. It is better than treated tap water in any case. You can use any container with a lid; it can be made of wood or even plastic. I do not use metal containers, however, because my plant feed could react with the metal during the fermentation process and produce unwanted by-products. At short intervals (every few days) I test the tea on things like areas of mould, aphids or scale insects and see whether it has the appropriate effect. If the effect is satisfactory the liquid fertiliser is ready and I can use it. If, however, the effect if still too weak I must continue to experiment. So I add more of one plant or another or I leave the tea to ferment for longer. This way more substances will be released and their effect will be intensified. After observing for a long time and experimenting in this way you can create your own recipe for an effective liquid fertiliser, that is the most appropriate to your local conditions.

While the mixture is fermenting it is important that there is enough oxygen in the container. This is why I leave the lid open a little during this time and stir the plant feed regularly with a length of wood. In warmer areas with strong sunlight the fermentation process is much quicker. On the whole, fermentation is complete in a month at the latest in areas that are not particularly sunny. I can tell the liquid fertiliser is ready because it is not foamy any more and it has a dark colour.

I do not think it is necessary to give an exact description of the plant mixture, temperature, quantity of water and plants or the amount to use. The safest and simplest way is to experiment and find out the suitable mixture in the concentration that is necessary for your area for yourself.

For instance, a mixture of plants that I often like to use consists mainly of: nettles (Urtica dioica, Urtica urens; they provide nitrogen), and comfrey (Symphytum officinale and Symphytum x uplandicum; provides potash). I also like to add tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), horsetail (Equisetum arvense) and wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). This liquid fertiliser is effective and improves the hardiness of the plants. It also works against aphid or scale insect infestations and against red spider mites, which is mostly a result of the wormwood. If I have too many of these ‘pests’ on my plants, I just increase the amount of wormwood until it has the desired effect.

Helpers in the Garden and Regulating Fellow Creatures

I would like to state that, in principle, there is nothing to fight in a healthy environment, because nature is perfect. Therefore, I must think about what effects my system has on nature. If I try to familiarise myself with natural cycles, then a great deal of thoughtlessly carried out actions become unnecessary or even wrong. Every creature has a purpose. The system will only become ‘unbalanced’ if it is incorrectly managed by human beings. Before you begin to fight ‘pests’, you should think about the causes of this damaging presence and change the conditions. Problems must be solved at the source. It is not enough just to treat the symptoms.

Here is an example: if I have too many aphids on my fruit trees, that means there are not enough natural predators (among these are ladybirds, earwigs, hoverflies, lacewings, various spiders, beetles and birds) and frequently there is not enough shelter or suitable habitat for them. If, on the other hand, I have a good habitat underneath the trees that are infested with aphids, and the ground is richly structured with stones, branches and leaves, the number of creatures which prey on aphids will increase. They will find an ‘open buffet’ and the overpopulation of aphids is quickly cut back. It is not necessary to take additional measures.

A crab spider (Thomisidae) on a daisy (well camouflaged) first lies in wait for its prey, and then consumes it. In a working food cycle there are no useful or harmful organisms, just fellow creatures – some, such as in this picture, are particularly beautiful.

There was hardly ever an overpopulation of ‘pests’ in our garden. This was mostly a result of the diversity and good structuring of old kitchen gardens. The more diverse a system is, the more stable it will be. Monocultures are favourable environments for the sudden large-scale appearance of a single kind of creature, because they find a surplus of food. The ‘pests’ jump from one feed plant to another, so to speak, because their natural predators do not find the right conditions in this wasteland. In a polyculture these problems can never arise, because there is always a wide variety of plants available. The spread of disease is also checked by this diversity. The valuable, helpful and beneficial creatures need suitable environments and places to hide and hibernate of their own.

These factors ensured that the Gachtl of my childhood was protected from large-scale damage resulting from pests. I can only remember a few times when the cabbage white population was much greater and descended on our vegetable patch. This overpopulation can be explained by continuous natural fluctuations in the population of pests and useful creatures. Nature works using the system of supply and demand. An increase in useful creatures balances out the increase in pests again after a while. If you resort to using chemicals in these situations, it will have the opposite effect, because many pests are more resistant to pesticides than their natural predators. So some of the pests will survive the attack and all the useful creatures will die, which can make the following wave of damage far greater. We checked the overpopulation of cabbage whites on the vegetable patch quite simply by spraying a liquid fertiliser composed of wormwood, stinging nettles, gentian root and horsetail on the cabbages.

The sand lizard (Lacerta agilis) likes sunny places, e.g. piles of wood or stones on unsurfaced ground. Thick vegetation in the immediate vicinity (flowering meadow, hedge) is preferable. Its diet consists of insects, spiders, woodlice and slugs, amongst other things.

Some of the most important creatures in the garden are: slow worms, lizards, hedgehogs, birds, amphibians, spiders and predatory mites. There are also many insects such as ladybirds, ground beetles, hoverflies, lacewings, earwigs, ichneumon flies and dragonflies. Only a small amount of energy is required to provide all of these helpers with a suitable habitat. The most important thing is for the garden to be richly structured and to resist making everything straight lines and tidily swept. The creatures need places to hide, nest and hibernate and a wide range of food to be happy. This is exactly what you need to provide them with. The edges of the garden are particularly well suited to this. Here you can, for instance, grow wild fruit and flowering hedges or even a variety of different wild flowers. It is a particularly good idea to put in tree stumps or gnarled hollow tree trunks. These can provide good areas for these creatures to breed and they are also very attractive to look at. Piles of wood, branches or brushwood can also fulfil this purpose.

Birds and bats can be encouraged with nesting boxes and the berries and fruit growing in a wild fruit hedge. Stones or piles of stones can also offer varied habitats, which can even be combined with a herb spiral if used carefully. Areas of water and wetlands enrich a garden greatly, because a population of amphibians and dragonflies can develop there.

Only a small amount of work is required to create sheltered areas of this kind and, with a little creativity, they can make the garden even more pleasant to look at.

Voles

Voles rarely appear in large enough numbers in our garden to cause damage. The reason for this is the following: in the confusion and diversity of plants the voles find enough to eat. They chew the roots of many different plants and shrubs; there is, however, no complete crop failure, because there is enough food for everyone. In the areas that have been gnawed on, the individual shrubs can repair themselves quickly and many new fibrous roots will grow around them. The voles also take many pieces of root away and store them for the winter, or feed them to their young. However, they regularly lose individual pieces of root in their extensive networks of tunnels. These tunnels are collapsed by rain or are colonised by other animals, and the voles must rebuild them. The lost salsify, black salsify, Jerusalem artichoke and carrot roots, to name a few, begin to sprout in the tunnels and new plants develop in the most unlikely places and in the most inhospitable areas. These are frequently places where you would never have thought to plant anything. The tunnels themselves drain off excess water and aerate the soil.

Many insects, plants and animals are territorial: they claim certain areas as their territory and defend them. According to my observations and experience it does not make any sense to fight voles, because once the territory becomes empty it will be used by new voles coming to the area. If I fight them (with poison, gas or by catching them), the territory will only become free for others. The lower population density will be balanced out by more and more empty territories. Voles will produce more offspring or even just produce more males. Instead of catching, poisoning or gassing pests, it is better to consider the cycles of nature. If I let the voles work for me, I will have aerated, loose and well-drained soil and also lush, diverse vegetation. The vole will no longer appear as a cause of damage. Moreover, poisoning and gassing will contaminate the soil. If the voles are exterminated on a large scale, the soil will no longer be well-drained or aerated; it will harden and become more acid and mossy. This will lead to many plants losing their habitat. The energy required to repair damage to the soil is much greater than the supposed damage caused by the voles eating crops. It is important to make sure that there are always enough decoy plants available to them. Decoy plants are particularly tasty plants, which the animals prefer to eat. Jerusalem artichoke and black salsify make very good decoy plants. If there are enough available, the voles will leave the fruit trees alone. It is not a question of what can I do to fight the ‘pests’, but what can I do for them, so that they will not cause damage and even work to my benefit.

Slugs and Snails

The situation is different with the non-indigenous Spanish slug (Arion vulgaris). Where we live the slugs breed on an enormous scale; in many places people have little idea of how to deal with this menace. Whilst giving consultations in Southern Styria and Lower Austria I discovered that on farms and in places where vegetables were being grown there were up to 15 slugs per square metre. Many farmers complained that the cattle would no longer graze, because the grass was so full of them. “Growing vegetables without using slug pellets is no longer an option,” was the opinion of the troubled landowners. The owners of gardens in town told me that the slugs would crawl up the houses all the way up to the balconies. In many cases, espalier trees and climbing plants had to be removed from house walls to discourage this.

A lush growth of decoy plants (here mostly Jerusalem artichokes) protect a newly planted orchard. Also to be seen are foxgloves (Digitalis purpurea), a highly poisonous medicinal plant (not to be used for self-medication), which I plant to improve the health of the soil among other reasons.

In smaller gardens the following method is very effective in my experience: take a watering can, cut the spout to half its original length so that it is much wider. Fill the watering can with a mixture of very dry fine sawdust, ideally collected from a carpenter or joiner’s workshop. The sawdust must, of course, come from untreated natural wood and not be varnished or contain any other harmful substances. I take the sawdust from a carpenter’s workshop, because the wood there is completely dry and the sawdust is much finer than you would find in a sawmill. Moreover, sawmills mostly work with fresh wood. I mix the sawdust with one part wood ash to ten parts sawdust, or with quicklime powder (around 1:20). Alternatively, you could use both, the only important thing is that all of the ingredients are bone dry. I fill the watering can with these materials and pour a finger’s width border of the mixture around the outside of the lettuce or vegetable patch. Make sure to free the border area of vegetation first. This border of sawdust mixture should remain as dry as possible. This means that from time to time, especially after is has rained, you will have to replace it. The fine dry sawdust mixture adheres to the foot of a slug or snail the moment it tries to get to the lettuce or vegetable patch. The ash and quicklime extract moisture, which prevents them from getting into the crop. If you sit in the garden in the evening, you will be able to see how the slugs and snails turn around when they reach this barrier and go back the way they came. Successes like these will quickly take the fear out of a slug or snail invasion.

There are many ways to regulate these pests naturally. Here is one more. Slugs and snails lay their eggs in dark, moist places. If you provide them with an ideal habitat to lay their eggs, you can regulate their population. To do this I make rows of freshly cut grass and leaves in the garden. They should be piled higher and compacted more than mulch, and should be kept as moist as possible, so that they provide the best conditions for egg laying. Slugs and snails will travel great distances to use places like these. On a particularly sunny day I then go into the garden and turn over the rows of grass with a gardening fork. Whole clusters of eggs will have adhered to the rotting grass. If you turn the rows of grass over at midday when it is at its sunniest, the eggs will rapidly be destroyed by the heat of the sun and the UV rays. The overpopulation of slugs and snails can quickly be counteracted with this method. If your neighbours also use it, the effect will be even greater. This method also demonstrates how much damage the improper use of mulch (using fresh material, piling it too high and not loosely enough) can cause.

Apart from these measures it is, as already mentioned, important to have the natural predators of slugs and snails as helpers in the garden. Excellent examples of these are hedgehogs, shrews, lizards, toads and many kinds of ground beetle.

The well-known edible snail (Helix pomatia) also helps to regulate the frequently large populations of slugs by eating their eggs. So not all snails are harmful!

Earthworms – Nature’s Ploughs

Earthworms are among the most important helpers in every garden. We have many local varieties on the Krameterhof. The brandling worm (Eisenia foetida), common earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris) and red earthworm (Lumbricus rubellus) tend to appear in large numbers in healthy soils. You can easily recognise the brandling worm by its dark red colour and its distinctive yellow bands. Common and red earthworms do not have this distinctive banding. Brandling worms are epigeal, i.e. they live on the soil surface. Red earthworms, on the other hand, only spend their youth on the surface and later they burrow into the deeper soil layers. Finally, common earthworms, which many think of as ‘typical’ earthworms, create burrows to live in and search for food at depths of up to three metres.

These three kinds of worm complement each other wonderfully in their work for gardeners: the brandling worm processes large amounts of organic material and provides the best compost. The common and red earthworms reach deeper layers of soil with their tunnels and aerate the soil well. The tunnels also work like an ingenious drainage system. The soil can retain more moisture; it does not dry out as quickly and is better protected from surface erosion. Plant roots can extend through earthworm tunnels better. Naturally, both of these types of worm also produce nutrient-rich compost for the garden. Earthworm casts contain much more of the plant nutrients nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus and calcium than can be found in the best garden soil. With their crumbly consistency they also provide a good soil structure. As a result of these factors, the vegetation develops much better with the help of earthworms. The plants are healthy and therefore more resistant to disease.

This is why it is important to provide the best possible living conditions for these valuable helpers. As earthworms are sensitive to UV rays, it is a good idea to make sure that the garden has permanent soil cover. This can be achieved with a mixed crop that is selected so as to avoid large areas being harvested all at once. Mulch also provides soil cover and attracts earthworms. If you find very few earthworms in your garden, you should by all means attempt to breed them yourself, particularly since this is easily acheivable in very small areas. Breeding earthworms is inexpensive and requires very little time. You can also ‘dispose’ of your organic waste. As an end product you will receive high quality compost for flower pots and the garden, and many energetic helpers. If you begin breeding earthworms on a large scale, you can even develop an additional source of income through the sale of worm compost and worms. In Europe and the United States there are a number of companies entirely dedicated to the breeding of earthworms.

Breeding Earthworms

In order to breed earthworms successfully you must research their natural habitat. Your own system will be designed accordingly. On a small scale, a wooden box with a capacity of one cubic metre is enough. Earthworms require a soil substrate of a mixture of straw, cardboard, soil and a little dung. In my other attempts I have also used different materials like natural fabrics (cotton, hemp etc.). The soil should be loose and well aerated. To ensure this, it is a good idea to incorporate layers of branches, leaves and roots into the substrate. Any cooking waste can be used as food for the worms. Onions and garlic are the only things I do not give to my earthworms, because I get the impression that they do not like it very much. The worms particularly like used coffee filters complete with coffee grounds. It is important to provide a regular supply of organic matter, so that the worms continue to get fresh food. The amount of food should be adjusted to the amount of earthworms. If the worms can break down their food as quickly as new food accumulates, the rate is optimal and harmful build-ups of mould will be prevented. Room temperature is ideal for the worms. A steady balance of moisture and a good supply of oxygen are also necessary. To avoid a build-up of water, holes should be drilled in the bottom of the worm box. The soil should be neither completely dry or completely wet; too much water will make the worms pale.

Plenty of worms can always be found in good garden soil.

You should observe the worms regularly. You will quickly recognise whether or not they are comfortable in their environment. Intuition is an important factor in creating the optimal conditions. In my greenhouses I no longer breed earthworms in boxes, but directly in the soil. To do this I use the soil substrate already mentioned, cover it with earth and put some worms in the pile. In the middle of this pile of earth I make a shallow depression. I can put fresh organic waste there each day and cover it with a few handfuls of soil. If when I’m feeding the worms the pile seems too dry, the waste quickly makes it moist again. If the system is designed so that it is well ventilated, feeding the worms every second or third day will be enough; this means that they can be left to their own devices over the weekend quite happily.

Along with the valuable humus and the numerous earthworms and worm eggs, breeding these useful creatures has yet another advantage: you will learn to observe and put yourself in the shoes of other creatures. Your ecological understanding and empathy will improve. From time to time when the weather is wet, I place the worms I have bred along with some soil and worm eggs in a bucket and scatter them over new terraces and raised beds in the evening. I use the nutrient-rich and fine crumbly worm humus for especially valuable and demanding plants and also for the flowers on my balcony.

Characteristics of Town Gardens

How Children Experience Nature

In principle, a garden in town has the same purpose as a kitchen garden. It is my opinion that town gardens are more important today than ever. If you live in a town and do not have the opportunity to grow up around animals and plants in forests and fields, you can at least experience a little nature in your own garden. The size of the garden is of little importance. The therapeutic effect of experiencing the marvel of creation in your own garden is a much more important factor.

I think back to my childhood when I planted my first horse chestnut, which I used to play conkers with, in a window box. My mother said to me, “If you plant that horse chestnut in the soil a tree will grow out of it.” She preferred her plants to be in window boxes on the sill in the kitchen instead of in the garden. My horse chestnut developed into a splendid little tree. I cannot describe the effect this had on me, because all of my later successes came back to that one experience. If children have the chance to grow up around nature, then they will be able to learn from it. It is incredible how much there is to discover. Intensive observation will inspire them with ideas that they will want to implement straight away. Learning begins and success will follow. Children do not give up easily, they are curious and have special access to nature. Their urge to discover motivates them to try again and again if they do not succeed the first time – that is the most important thing: to never give up and to learn from your mistakes. Children need praise and to have successes, this makes them strong and encourages creative and independent thought. Children still have room in their heads to retain their own observations and experiences of natural cycles. These memories will stay with them for their whole lives. My childhood experiences have helped me always to come back from the wrong path and find a natural life in harmony with nature. If you isolate children from nature, cut them off from their roots in a manner of speaking, they will not understand causal relationships and cycles within nature. As they have no roots, they will find it harder to handle problems. That is why if you live in town you should still give your child the chance to sow radishes or carrots in the garden or in a window box, and to watch them flourish. This will allow them to make observations about insects and experience the colour and smell of plants. The desire to discover nature exists in every child, if the parents do not educate it out of them or forbid them to go any further into its secrets. How often have I heard: “Don’t get dirty, the ground is filthy”, or “Come away, leave that alone.” The same goes for when children point out a butterfly, a bumblebee or a beetle to their parents. It is not uncommon to hear: “Leave it alone, yuck, that is horrible, come away. It’s poisonous, it’ll bite you and, anyway, you’ll get dirty.” In my opinion, this is one of the biggest mistakes a parent can make. You should give the child your attention and ask: “Oh, what have you found there?”. Try to find out what kind of worm, beetle or butterfly it is. You could look through a book on insects with your child in the evening and work out what they found. This way your children could grow up having a relationship with nature even if you live in town.

Children should have the chance to grow up around nature. These are my grandchildren: Helmut, Elias and Alina.

Design Characteristics

On the whole, everything that applies to a kitchen garden can also be applied to a town garden. If there is only a small area available, then it is even more important to design and use it optimally. In small town gardens, for example, valuable space can be gained by creating raised beds and terraces. The same principles apply in this situation as those already described in the chapter ‘Landscape Design’. These techniques will provide microclimates, visual barriers, windbreaks and protection from erosion. As a result, incoming pollution will be minimised (especially fine dust) and noise pollution will be mitigated. All of these factors are beneficial for a town garden and should not be underestimated.

Before the landscaping begins, the existing soil must be examined. When doing this all of the factors previously mentioned in the section ‘Soil Conditions’ are important. It is possible for the soil in town to be so heavily polluted, that you will have to replace it with uncontaminated soil from an organic farm before you can begin work on the garden. Although this is costly, with some soils it is sadly necessary. Over time, an active soil life should develop in this soil, which will find the best conditions and will be encouraged by the use of mixed crops, and the lack of chemical pesticides or chemical fertilisers. The regenerative power of the soil will be enormously improved by this, to the extent that you will be able to grow high-quality produce in town. If the soil is heavy loam, which is water and air permeable, it is possible to loosen and aerate it by mixing in sand, straw, leaves and chipped material (wood chip). If you are using an excavator for landscaping, you must first find out whether there are any telephone cables or gas, water or sewage pipes in the ground and exactly where they are.

Lush and diverse plant life can even develop on the west side of the Krameterhof, which is in shade.

Fruit tree as a ‘climbing aid’ for tomatoes.

When shaping a small garden it is particularly important to make the most of the sunlight. If you do not select your plants carefully, the whole garden will quickly become shaded. This is why tall-growing trees should not be planted. If there is a house or shed wall available, the masonry stove effect of the bricks that I have already described will be at your disposal. The heat retention and radiation qualities of the wall makes it suitable for fruit trees that need a large amount of heat (peach and apricot), and can be planted as espalier trees. A system of tiered terraces – in other words, using vertical surfaces in every possible way – is of great advantage in small areas. On the different terraces, shrubs and fruit trees can be planted at staggered heights. The trees can then be used by grapes, kiwi fruit, cucumbers, pumpkins, courgettes, peas and beans as climbing aids. This way the heat retention and radiation aspects of the walls will be used effectively. The interaction between the nutrients released by the individual plants in symbiotic communities of this kind is shown to best advantage. You can create a real ‘jungle garden’ that offers a place to recuperate and relax, in addition to providing delicious produce. Naturally, you must find out how high the different shrubs and trees will eventually grow before you plant them. This way you will save yourself the work of constantly having to prune and trim everything back.

In gardens where the sunlight reaches areas abruptly because of tower blocks or other buildings, you must make sure that it does not hit any frost-sensitive trees, which are in full flower, too suddenly (e.g. apricot, peach or early cherries). Although these trees can withstand light overnight frosts without taking damage, abrupt sunlight can put them into shock, which can lead to the loss of all their leaves and flowers. In this situation you should place trees in areas where a shock of this kind can be avoided, instead of positioning them by the sunny house wall, which would otherwise be optimal. Overnight frost can thaw slowly in the shade, which has less serious consequences for the tree. The fruit will ripen a little later and might not be as sweet, but this compromise is necessary for there to be a harvest at all.

The conditions that can be found in town gardens vary greatly. This is why it is important always to remember the principles of permaculture and to treat your own patch of land with empathy and creativity. Then you will find plenty of ways to grow vegetables, medicinal and culinary herbs, berries, fruit and mushrooms in only a few square metres.

Terraces and Balcony Gardens

Permaculture principles can be made a priority and put into practice on balconies, terraces, small green areas and even in houses. In fact, I even had a small plant tub in my first ‘garden’. I was sceptical at first, but you really can grow anything, no matter how big or small, in a container like that. I have planted up balconies and terraces in many different towns. To start with there are usually just ornamental trees or bushes like cotoneasters, junipers or dwarf Alberta spruces on the terraces or balconies, mainly because they do not need much care and are ‘green’. Usually, everything is very homogeneous; this is probably because it is stipulated by the house rules or there is too little flexibility. Balcony, terrace and even normal gardens can be found with hardly any variation in design or plant selection throughout all of Europe. I continue to hear from the owners of gardens like this, that nothing else would be able to grow on the 10th or 20th floor anyway, and certainly not fruit or vegetables in any case! Then they often comment that they do not know what the neighbours would say if they suddenly saw radishes, peas or even beans growing in a plant tub. I encourage people to just break this taboo and make their own balcony or terrace garden into an edible garden regardless. My methods and suggestions have been put into practice successfully again and again.

Medicinal and culinary herbs and even vegetables can be cultivated on a small balcony.

Let us use the example of a small terrace, two metres by three, that is facing away from the street. At this point I should mention that you need to keep an eye on the amount of pollution coming from roads or factories when cultivating food in town. On busy streets it is better not to use the sides of the house that face the road to produce food. It is also a good idea use the walls of the house by planting climbing plants like clematis. This can also create a microclimate by adding an insulating layer that can cool the house in summer and help retain heat in winter. Areas that are a little more sheltered and at the back of the house are, however, very well suited to the production of food. At the front of the terrace you could place two concrete troughs with a combined capacity of around one and a half cubic metres of soil. Drill one or two holes with a diameter of approximately 10cm in the bottom of each trough. Put some bricks or wooden posts under each trough so that there is a space of around 15 to 20cm between them and the ground. In this space put a waterproof tray. Now you can insert a hardwood trunk in through the hole in the tub. Make sure that the trunk is narrow enough to fit through the hole, whilst still leaving space for water to trickle through. As long as the trunk fits in the space available, it can be as tall as you like. This acts as a climbing aid for grapes, kiwi fruit, courgettes, cucumbers, pumpkins, beans, peas, roses and various other climbing plants and it can also be used for the cultivation of culinary mushrooms, as I have described in the ‘Mushroom Cultivation’ chapter. If you select a particularly attractive trunk (with pleasingly twisting side branches), the garden will look even more pleasant. Directly around the hole in the trough (around the trunk) place enough broken bricks or gravel to provide drainage and prevent a build-up of water in the trough.

The trunk in the trough can now be drilled in a number of places and inoculated with mushroom mycelium. Then the trough is filled up to around two thirds with healthy soil mixed with broken bricks. You should not use commercial potting soil for this, because it contains large amounts of peat, which is harvested at the cost of our moors and does not have any kind of fertilising effect! Earthworms are also introduced into the trough. Then the planting and sowing can begin. The climbing plants are wrapped around the trunk and various vegetables (lettuce, radishes, peas etc.) can be planted or sown next to them. The more you manage to make use of different levels, the more green material you will be able to fit in a small space. An arrangement of plants at staggered heights achieves this best. Plants that gr

Colourful combination of plants by the wall of the house.

ow to different heights can be positioned so that no competition will arise.

Fill the tray with water. The hardwood trunk (the criteria for selection can be found in the chapter ‘Mushroom Cultivation’) ‘sucks’ the water up from the tray and balances out the moisture of the soil in the trough. If the trough is left outside in the elements, enough rainwater will collect in the tray to keep the trough moist. Otherwise, it will need to be filled up by hand, or the plants will have to be watered. If you have a gutter, you can keep the plants supplied with water automatically. Fix a section of drain pipe into the tray from the gutter and put in an overflow that leads back again (include a sieve, and position the overflow at least 10cm higher than the inlet pipe). However, in cities you should be careful about using this method of irrigation, because the roofs there are often very dirty and ash, soot and many harmful substances could accumulate in the gutters. If, on the other hand, your house is in a less heavily populated area, you can use this method of irrigation and go on holiday without having to worry that your balcony garden will dry out.

Organic waste from the kitchen can also be incorporated into the soil in the troughs each day with a trowel. The waste should always be used fresh and placed in a different area each day. It should be covered with leaves or mulch whilst making sure that plenty of air can reach it. The organic waste provides the worms with food and the plants with high-quality fertiliser. Over time the trough will, of course, fill up and the result will be a substrate with an enormous amount of worm eggs and young worms that can then be used in plant tubs, flowerpots or in the garden.

The liquid fertiliser that I have already described can also be used to protect the plants on a terrace or balcony and increase their resilience (against aphids and fungal diseases like mildew among other things). The mixture you use will depend on the number of plants and the available space. The plants required for the liquid fertiliser can be obtained on a walk through the countryside or through a forest. Some liquid fertilisers develop a very intense odour. If the smell bothers you, something can be done about this easily: simply stir in some stonemeal and the odour will be neutralised, valerian can also be used. If you do not want to make liquid fertiliser you can use herbal tea instead. Chamomile tea, for instance, has an antibacterial effect and can be used to prevent root diseases. Tansy is very effective against root lice and can be used to treat rust. The tea can be used as soon as it has cooled. It is a matter of preference which method you decide to use, because the plant mixtures are just as potent when they are prepared as a tea, an extract or as diluted liquid fertiliser. Your own experiments will, over time, lead you to the best mixture for your balcony.

With time the climbing plants will stabilise and become woody (grapes, kiwi), so that they will no longer need additional support. This means that it is not a problem when the trunks inoculated with mushrooms lose their load-bearing capacity over time.