1

At its narrowest point, the mighty Danube thunders through a narrow gorge, the Gate of Trajan,* cut by the river into the limestone bastions of the Carpathian Alps. Lupa, the she-wolf, stood at the edge of the gorge gazing down at the small figures making their way up the banks of the river a hundred metres below. They did not provoke in her any particular reaction. Humans had been using the river in this way for as long as she could remember. She and her pack did not have anything to do with the humans, but all the same she liked to keep an eye on them when they were in her territory. She knew the humans as brave hunters but they moved far too slowly to be very effective. They would eat anything that moved, including her fellow wolves if they could catch one. But that very rarely happened, and only if a wolf was sick or injured in some way. Earlier in the year, Lupa had watched the humans ambush and kill a young mammoth by driving it over the edge of the cliff, though this was unusual and most of the time they seemed barely able to scrape a living. For Lupa the main thing was to leave them alone and avoid unnecessary confrontations.

As the river mist lifted with the first rays of morning sun, Lupa could see the humans more clearly and, with her acute awareness of every detail of her surroundings, she sensed that they were a bit different from usual. They were a little taller, a little slimmer perhaps and moved a little more, how would she put it, a little more gracefully. Probably nothing in it, she thought to herself. Even so, I’ll keep a close eye on them. She turned away and trotted effortlessly back across the undulating grassland, dusted by an early frost, to join the rest of the pack. It was October and winter was well on the way. The river had begun to freeze over and the last of the reindeer had already moved down from the high plateau to their wintering grounds on the river estuary. It was time for Lupa and her pack to follow them, and next day she led them on the long trek downstream towards the Great Black Sea.

Along with Lupa and her mate of two seasons there were four young wolves in Lupa’s pack, two from this year’s litter and two from the year before. The pups, born in June, were just old enough to learn to hunt. Before that the pack was too small to be viable for long and it had been hard work getting enough food over the summer. As always, it was Lupa who organised the hunting. She decided what prey to target, even which animal to go for. She planned the chase to take advantage of any variation in the contours of the landscape and decided where to set any ambushes. The pack was completely dependent on her skill and leadership.

Meanwhile, the humans at the bottom of the gorge were not aware that they were being watched. They knew about wolves, of course. They occasionally came across one in the forests and were familiar with the eerie howling that kept pack members in touch with one another. But in general humans and wolves kept themselves to themselves. The new type of human, Homo sapiens, that Lupa had seen from her vantage point at the lip of the gorge had other things on their mind. The first of these was that the gorge was also home to Neanderthals. They were noticeably different in appearance, being much heavier set and therefore stronger, but at the same time were less agile. Neanderthals and moderns tolerated each other and, in fact, occasionally interbred. The biggest difference between the two human species was invisible. The Neanderthals were not as smart or inventive. They hadn’t changed their hunting methods or equipment for at least 200,000 years and showed little sign of ever doing so. The moderns on the other hand were always thinking of new ways of doing things. New designs of stone tools, of bows and arrows, the invention of the atlatl, or spear-thrower, and of all sorts of personal adornments. In time, these improvements would spell the end of the Neanderthals, and now there was one other innovation that was about to make an impact, a coalition between wolf and human, something the Neanderthals had never even contemplated.

The caves lining the Gate of Trajan were a favourite hibernation site for one of the most feared animals of the Upper Palaeolithic, the cave bear Ursus spelaeus, half as big again as the brown bear and with a voracious, omnivorous appetite for food which, from time to time, included humans, both Neanderthal and modern. Whereas Neanderthals abandoned the shelter of the caves as soon as they heard or smelled a bear nosing around, moderns had learned to leave the caves in the autumn and return a few weeks later when the bears were hibernating and kill them where they slept. This gave them vacant possession and enough meat to help them through the winter, should they wish to stay.

By early March the days were getting longer, although not appreciably warmer, and Lupa knew it was time to make a start for the high ground. The wolf pack had survived the winter by feeding off the herds of reindeer and wild horse which overwintered on the delta. But first there was the business of mating. Lupa was only receptive to the alpha male for five days every year. That was enough for her to get pregnant once again. She wanted to be sure to reach her traditional denning site in the hills in good time for the birth of her cubs. Very early one morning, with the frost decorating the dried stems of last year’s reeds, she led her pack away from the delta and headed west for the mountains.

In past seasons Lupa had arrived in the gorge ahead of the Neanderthals, who had also spent the winter on lower ground. This year she was surprised to see humans were already living around the gorge when she arrived with the other wolves. She made her way to her usual birthing den in a small cave hidden behind a patch of eroded scree high up on the side of the gorge. Ten days before the cubs were due, she settled down and waited for the births. For the period of her confinement the alpha male ran the pack. All the wolves brought food to Lupa which they left outside her den.

In due course Lupa gave birth to four blind cubs. One, the weakest, died almost immediately, but the other three developed quickly. Their eyes opened at two weeks and a week later they were beginning to feed on regurgitated meat. The following week, Lupa led her pups outside the den for the first time where they played under her supervision. The other wolves who had kept Lupa supplied with meat during her confinement now began to do their share of babysitting, giving Lupa a well-deserved break.

The first thing she did was to walk to her favourite lookout at the edge of the gorge to see what the humans were up to. She could see a small group paddling in the river, overturning stones and occasionally plunging their hands into the icy water to pull out a crayfish. This is something the Neanderthals never did. But the biggest surprise was still to come. On her way back to the den she saw not far away on the plateau a group of humans who appeared to be hunting. The Neanderthals never came up to the top of the gorge. These strange new humans were the same slimmer version she had seen the year before. Unsure what to make of them, she kept low to the ground out of sight behind a clump of dwarf willow.

Over the rest of the summer Lupa and her pack saw more and more of the humans up on the plateau.

She saw them ambush a wild horse they had deliberately separated from the herd. They had it cornered in a patch of marshy ground below a low bluff where it became trapped in the mud. Two of the humans – there were six in all – climbed the bluff with spears in hand. While the others spread their arms and shouted to confine the horse and prevent it from escaping, the two on the bluff raised their spears and hurled them into the struggling animal. It shuddered and dropped to the ground. All six humans crowded round the stricken beast and drove their spears deep into its chest. Once it was dead they took out stone knives, opened the abdomen and shared the liver between them. They then butchered the rest of the carcass and made their way back down the gorge. Not all their hunts were as successful as this, and more than once over the summer Lupa watched as the exhausted humans made their way home empty-handed.

The first flurries of winter snow fell on the high plateau in August and the reindeer were once again on the move to lower ground. The first snows heralded the best month’s hunting of the year for the wolves. Calves born in May were now almost fully grown but were inexperienced. The wolves knew which routes the animals would take across the undulating plateau and planned to intercept them in the pockets of soggy ground that lay in their path. Lupa led her pack, now nine strong, towards the ambush zone, many kilometres from their home near the top of the gorge. But something was troubling her. She stopped and sniffed the air. There it was again, the same scent she had first encountered at the site where the humans had killed and butchered the wild horse a few weeks earlier. Not only was Lupa’s olfactory sense very acute, she was also able to remember smells for months or even years. She knew very well the pungent scent of the Neanderthals, but this was certainly different, still strong but a little sweeter. Scent always being her primary sense, from now on she would recognise the new humans using her nose rather than her eyes. She scanned the horizon. She could not see any humans. She led her pack onwards.

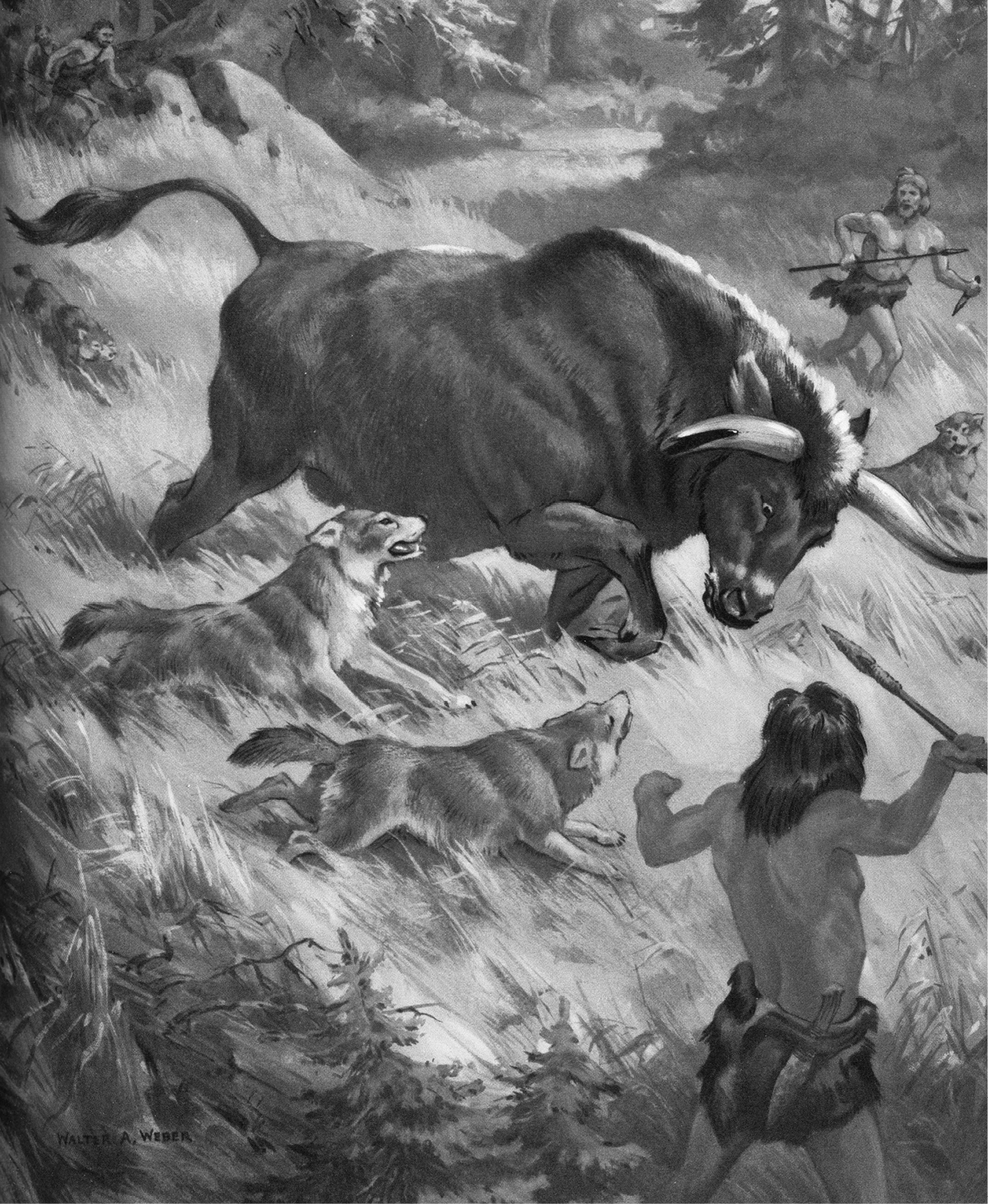

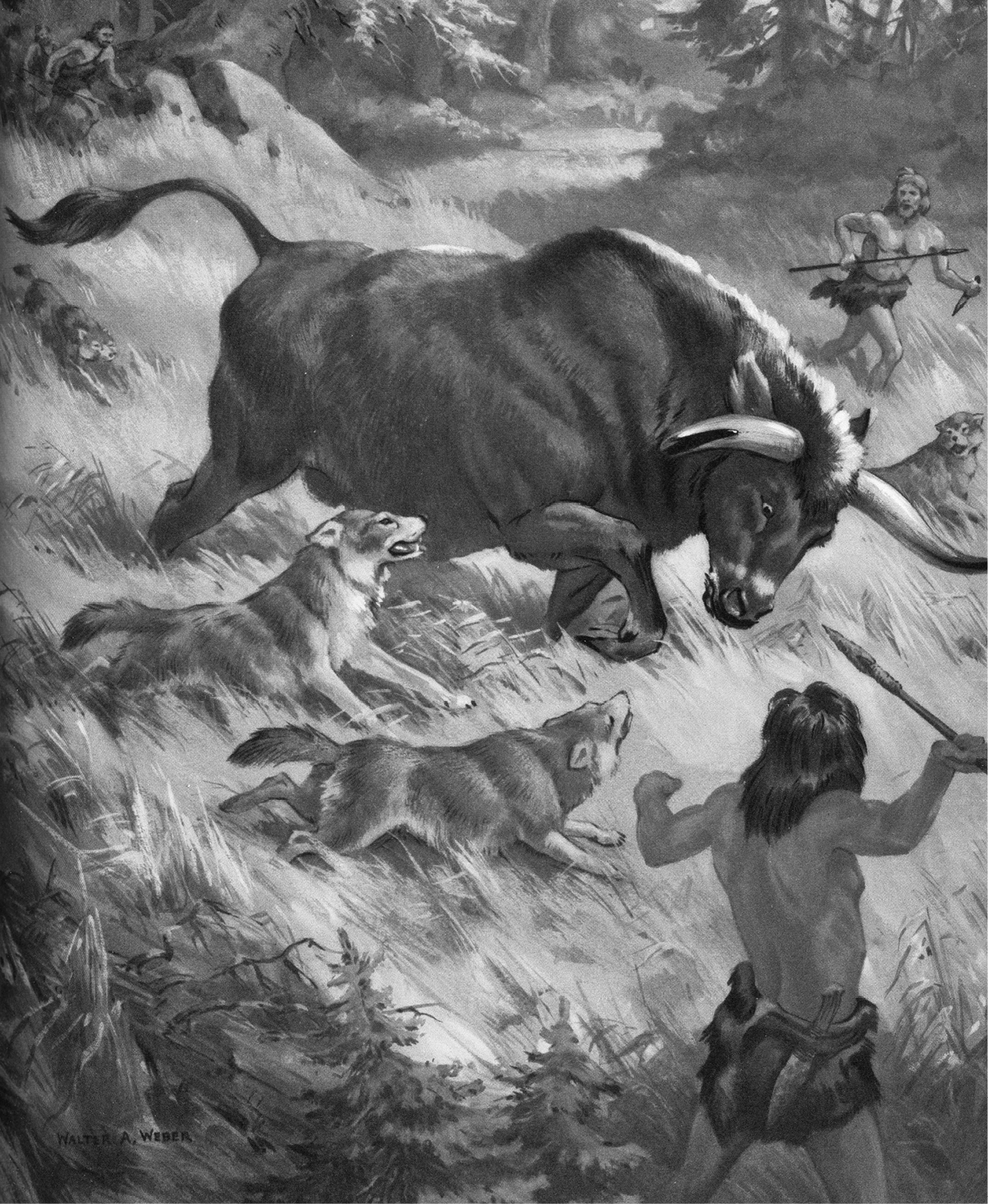

Suddenly from a small clump of birch trees about twenty metres away an enormous bull aurochs charged out, heading straight for Lupa. These giant beasts, the ancestors of domestic cattle, had very short tempers and were extremely aggressive towards wolves. Lone bulls like this one were worst of all. Wolves knew better than to take on an enraged aurochs. It would take a much bigger pack than Lupa’s to subdue and kill such a giant. Before she had time to organise the rest of the pack, the beast was on her. She just managed to dodge the deadly horns on the first pass and moved backwards out of range. Seeing her in trouble, the first instinct of the rest of the pack was to protect its leader. The alpha male rushed into the attack, attempting to sink his long canine teeth into the beast’s huge neck. With a flick of the bull’s head the wolf was skewered on the aurochs’s left horn. Another flick and the bloodied body was flung to the ground. The other wolves went to attack, still desperate to protect their leader. The thrashing bull caught one of this year’s cubs full in the chest with its back leg then turned and trampled the winded and mewling animal and left it dying on the moss. Lupa herself now joined in, knowing full well that if she was killed or injured the pack was finished.

Just then, two humans appeared downwind over the crest of a low hill. They had been tracking the aurochs. They had heard the commotion and now they saw the reason for it. Standing well back, they took up position and hurled their spears at the snorting bull. The sharpened flint tips found their mark. One spear struck the animal in the flank while another buried itself deep in the beast’s chest, its razor-sharp edge severing the aorta. Blood spurted from the wound and the beast fell to its knees. It lay there quivering and within a few minutes it was dead.

The two humans advanced on the carcass, knives at the ready. They looked up, expecting the wolves to retreat, but instead they held their ground and lay watching in silence. The hunters opened up the animal and removed the steaming entrails. They cut slices from the warm liver and began to eat. When they had taken their fill but before they started to butcher the carcass, the younger of the two hesitated. He had seen how wolves ran down their prey, following them for many kilometres until the animals, weak from exhaustion, could fend them off no longer. Once they were sure the death throes no longer put them in danger of serious injury, the wolves would engulf the dying animal, ripping at the exposed abdomen and disembowelling it. An idea was beginning to form in the mind of the hunter.

Reaching into the ribcage of the fallen aurochs, the younger man ripped out its still-beating heart and tossed it towards the wolves, much to the dismay of his older companion. Still the wolves stayed where they were, their amber eyes fixed on the humans. After a full five minutes Lupa was the first to move, gingerly advancing towards the offered heart. The other wolves watched in silence. Lupa sniffed at the heart, then opened her wide jaws and sliced off a chunk of the left ventricle and began to eat it. Still the others did nothing. After a further five minutes, with an almost imperceptible movement of her ears Lupa sent a silent signal to the rest of her pack. They advanced and tore the rest of the heart to shreds.

When both wolves and humans had gorged themselves on the beast’s entrails they sat there looking at each other. Something passed between them. Was it a spirit message? Was it merely mutual admiration between hunters? Did either of them know what had just happened?

Over the years that followed, wolf and human grew closer together. The next spring, as lines of reindeer moved towards the skyline through purple meadows of crocus and gentian on their way to summer pastures, wolf and human followed to pick off the stragglers. Increasingly easy in each other’s company, they no longer kept their distance and it was not long before they began to cooperate in the hunt. Sensing a weakness among the reindeer, Lupa picked out the target animal in the herd. The pack trotted off in pursuit, with the humans following as best they could. As the isolated deer began to tire, the wolves formed a circle and held it at bay until the humans arrived to kill it with their spears. Because the wolves no longer needed to completely exhaust the animal in order to avoid injury, the chase was over more quickly. For their part, the humans had a static target for their spears. All shared the kill.

An Artist’s recreation of what a collaborative hunt, like Lupa’s, might have looked like. The wolves harry the aurochs, tiring it out, while the humans inflict the killing wounds from a safe distance. (© GraphicaArtis)

Wolf and human benefited from this collaborative hunting, and in the years that followed, long after Lupa had died, both groups learned to adapt and improve it. Wolves began to signal the presence of prey with a low-pitched howl. Humans understood the message and a hunting party set out to join them. Wolves and humans who hunted together prospered at the expense of those who did not. Their numbers increased and gradually the unstoppable current of natural selection spread this symbiosis across the rest of Europe. Eventually some wolves began to live with humans, intermittently at first, then permanently. Their numbers increased even more and, from this beginning, dogs began to evolve.

All this happened a very long time ago in the high and wild country above the Gate of Trajan. That was the start. We have yet to reach the end.

* Named after Roman Emperor Trajan (ruled 98–117 CE) and marking the northern boundary of the Empire.