2

It’s easy to pinpoint the moment when the collective view of how humans and all other animals and plants came to be changed abruptly. On 24 November 1859 the naturalist Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The main contention of the book, that species were not fixed and could change over time, immediately challenged the predominant view of the Church that all of nature was deliberately and carefully designed by God himself. Humans were created by God in His image and, as such, occupied a special place above all other animals. The fact that all naturalists at the two predominant British universities, Oxford and Cambridge, were enrolled as Church of England clergymen as a condition of their employment only strengthened the grip that this ‘natural theology’ had on scientific opinion. To disagree was dangerously close to heresy.

At the heart of Darwin’s theory of natural selection was the concept that individuals within a species differed in their ability to survive and reproduce. Those that succeeded in what he referred to as ‘the struggle for survival’ passed on these qualities to their offspring, who were then better able to endure the struggle. Consequently, over time, new species evolved and others became extinct.

In many ways, Darwin was unlike any modern biologist. He knew nothing of genetics, the underlying principles of which lay undiscovered until well after his death in 1882. Nor did he work in a laboratory. Instead he relied on extensive correspondence with hundreds of his contemporaries throughout the world, persuading them to pass on information and sometimes to examine or collect specimens on his behalf. By these means, his accumulated wisdom and knowledge were immensely broad, which is what makes his writings such a joy to read. His theory of evolution took decades of development and refinement. Most of these were spent collecting a wide range of examples of his theory in action until he finally felt ready to publish.

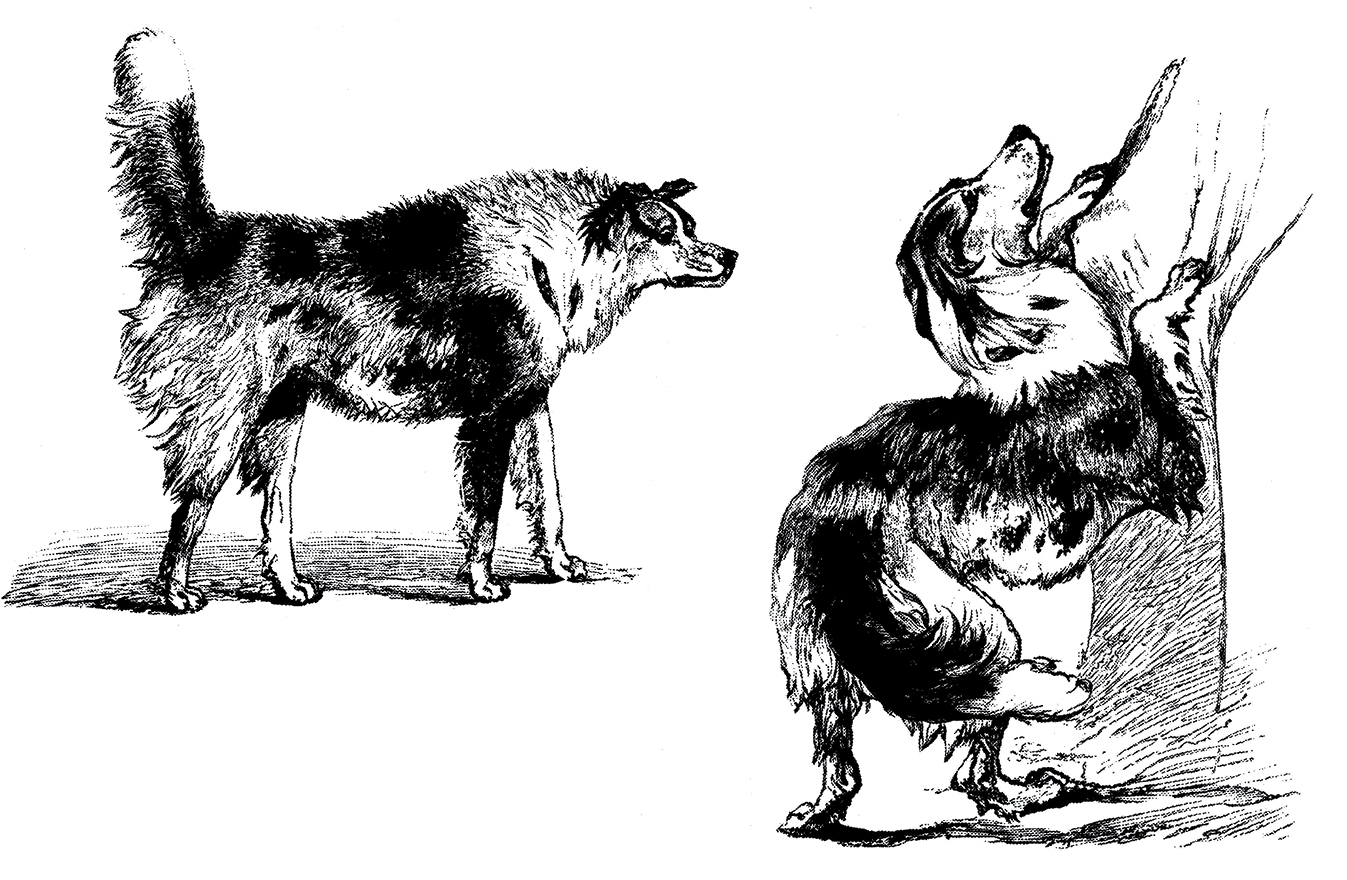

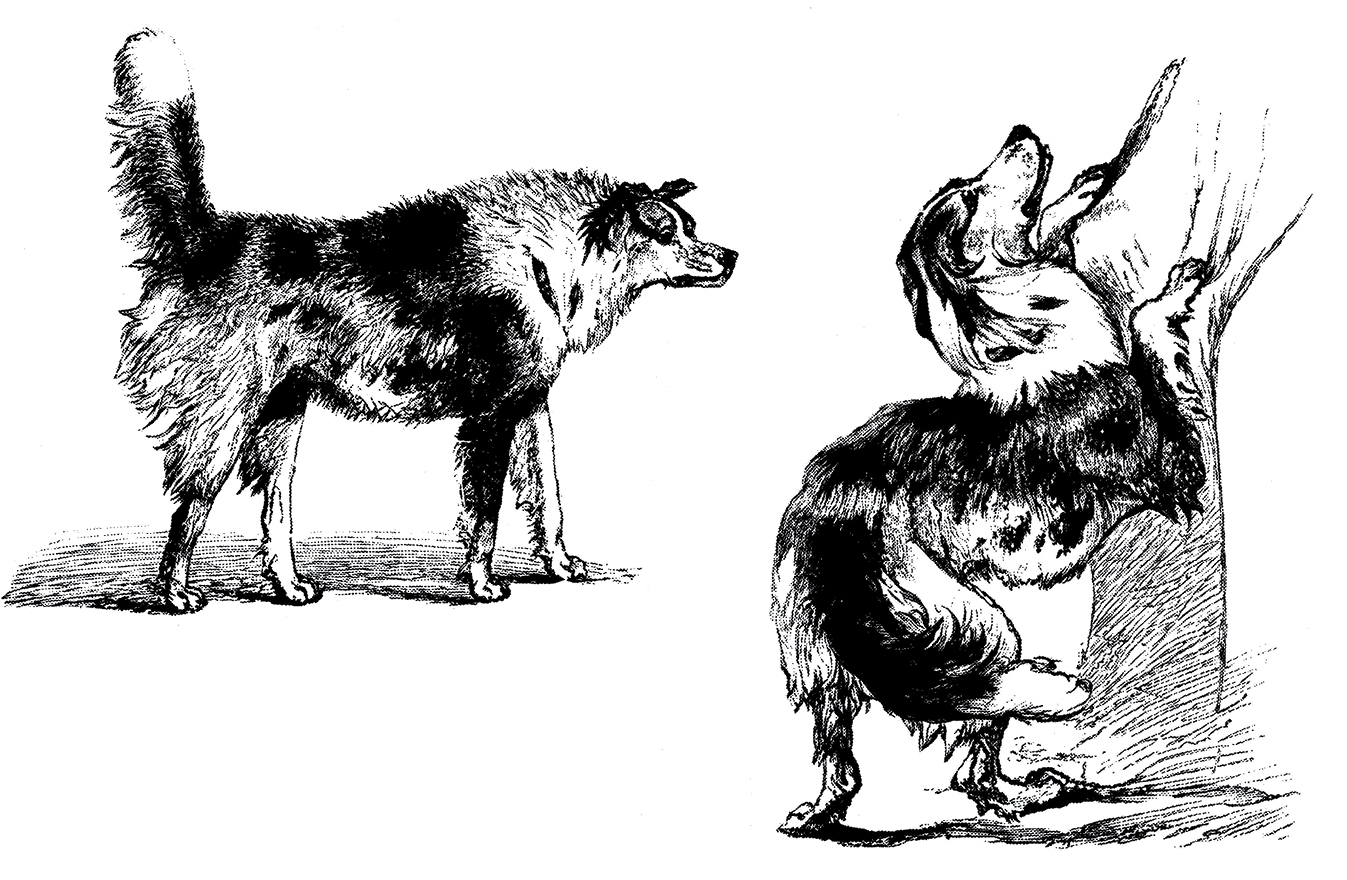

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals by Charles Darwin was published in 1872. Darwin’s book is among the most enduring contributions to nineteenth-century psychology and a testament to his fascination with the dog. The left illustration is captioned, ‘Half-bred Shepherd dog approaching another dog with hostile intentions’. The right, ‘The same caressing his master’. Both were drawn by A. May. (Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

One important strand was Darwin’s observations of the creation of new forms by deliberate breeding, which he referred to as artificial selection. His favourite examples were the extravagant strains of domestic pigeon created by fanciers, the main reason being that he was pretty certain that they all descended from just one wild species, the rock dove Columba livia. As in all his work, Darwin was thorough and meticulous. He kept the main varieties of pigeon himself at home, and through his network of contacts collected as many skins as he was able from far and wide. He spent days in the collections at the British Museum and even enrolled in two London pigeon-fanciers’ clubs.

As well as pigeons, Darwin studied pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, horses and asses, domestic rabbits, chickens, turkeys and ducks, even goldfish, not to mention plants of many kinds. And, importantly for us, dogs. The first chapter of his accumulated thoughts on evolution through artificial selection, published in 1868 as The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, is devoted entirely to dogs.

Right at the start Darwin sets out the principal question surrounding the origin of dogs.

The first and chief point of interest in this chapter is whether the numerous domesticated varieties of the dog have descended from a single wild species or from several. Some authors believe that all have descended from the wolf, or from the jackal or from an unknown and extinct species. Others again believe, and this of late has been the favourite tenet, that they have descended from several species extinct and recent, more or less commingled together.

Then he adds: ‘We shall probably never be able to ascertain their origin with certainty.’

Darwin’s questions on the origin of dogs remained unanswered for over 120 years until the new science of molecular genetics began to take an interest. In the chapters that follow we will explore what this new science has to say about the evolution of dogs and how, for once, Darwin has been proved wrong. We have been able to ascertain the origin of dogs with certainty.