12

Aloha Mahuakine: A Story in Pictures

By: Emma Burger

Or how my mom went from here:

to here:

And back here again:

And back here again:

I wish that this story were decades longer. I wish I could write a novel about my mom’s life instead of a short story, but this is all I have. After she died, someone told me that “at least we still have pictures.” I can’t imagine someone actually thinking this was of real comfort to a five year old who had just lost her mother. A photo can’t take you to your first day of school or push you on the swings at the playground. A photo won’t be there to sing to you on your birthdays, and you’d just look stupid if you tried singing to the photo on its birthday. You can’t sit on a photo’s lap, and it won’t stroke your hair or call you Emma Kai-Lou and tell you that it loves you. Despite this, I’m so grateful now to the person who told me that then, because without these photos, I’m just not sure how much I would remember. In Kaui Hart Hemmings’ novel The Descendants, a strikingly similar story about the life and death of a wife and mother of two girls in Hawaii, Scottie (the younger daughter in the family) makes a scrapbook of her mom as she is dying. Here is mine.

In 2000, my parents planned a trip to Hawaii. First we went to Honolulu in order for me and my sister to meet our great-grandmother Mama-san, and for my mom to unknowingly tell her grandma goodbye.

After staying in Honolulu with Mama-san for a few days, we got on a small airplane for our short flight to Kauai. We rented a house there for two weeks, right on Waimea Bay. This was where Mom showed us Hawaii: we went to the beaches, listened to the ukulele, ate shaved ice, tried in vain to hula without looking painfully white, and came out unscathed by the horrors of Hawaii’s favorite mystery “meat,” Spam. I could see that this was her place, her paradise.

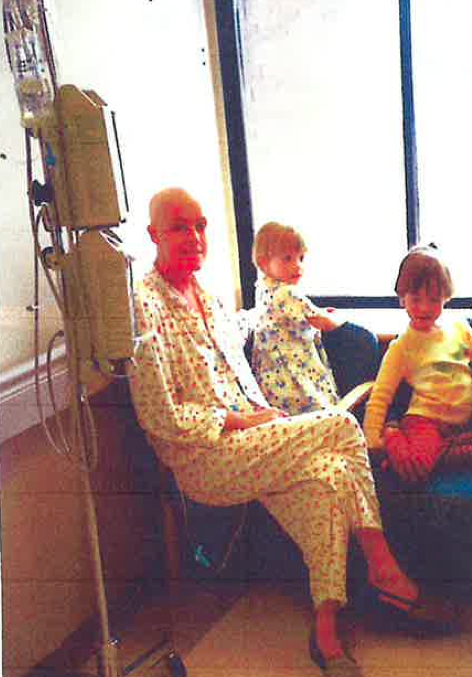

In December of 2000, just months after our trip to paradise, my mom was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer of the blood. I remember her saying one day that her stomach was killing her. She went to the doctor, and a couple days later we found out the diagnosis: turns out she was spot on when she said it was killing her. The next seven months were not easy. At first she was outpatient. She could still live at home but she would have to go in to the hospital and the cancer center. But she started going out less, wearing her pajamas more, taking a large collection of meds, and losing weight. She started chemo and refused to let it beat her, so she had my dad shave off all her hair before it could start falling out. They went into the kitchen with my dad’s electric razor, and I peeked in as her dirty-blonde hair fell to the floor.

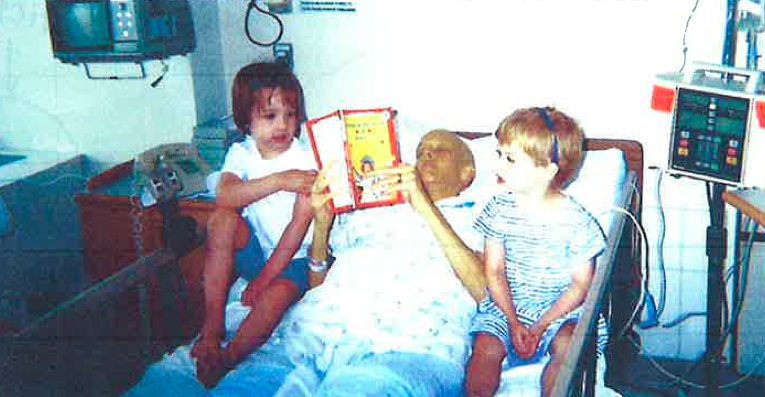

Once the chemo got more frequent and intense, she had to move to 16 East at St. Vincent’s where she was receiving treatment, only really leaving briefly to go to the cancer center in the East Village. My sister and I went to Barrow Street Nursery School just a few blocks away from the hospital, and every day after school we would visit. That year, my grandma and great-aunt moved to New York to help. My sister and I had a fantastic babysitter Lori helping us, and so many of my mom’s friends came to visit her.

I think they kept it like this for my mom, but also in part for my sister and me. There were distractions all around the hospital. We would play games, Mom would read to us, the nurses brought us candy, and would walk around the floor with us. Mom was getting worse, Chemo was draining her. The cancer was spreading, and although I never noticed, she was getting paler, weaker, skinnier, and more tired. We started to come twice a day, once after school and once in the evening right before bedtime, my sister and me in our pajamas. But still, everyone would say “She’ll be okay… she’s a fighter” (229). One day, my dad and my grandma led me down the hall to a side room with a big table and chairs all around it. They told me to sit down, as if the weight of what they were about to say would knock me over. “Your mom is going to die,” my grandma said. “But she might not!” I remember saying it over and over again until my face was red and everyone in the room was crying. “She might not, but she probably is,” my dad said. But I didn’t believe him, I couldn’t believe him or it would be true, “but she probably won’t! She might not die, she might not die, she might not die.” I said it over and over again so I could know it was the truth. And then I buried my head in my dad’s sweater and cried.

A few weeks later, it was mid-July and we were spending every spare minute in the hospital. My dad was sleeping there, although I have a feeling he was not really sleeping. Mom was making up for any lost sleep though, because that’s almost all she could do at this point. But then one day, July 25th, we went to visit, and she became herself again. She was still tired, sick, and quieter, but there was a spark of energy in her. Naturally, I thought she was getting better.

I realize now that my dad was right. He knew the weight of what he was saying when he told everyone “No, she won’t be fine. She’s going to die. We’ve taken her off the machines” (229). The doctors stopped chemo and radiation, took her off the drugs, amped up the pain killer dosage, and were letting biology do its work.

On the morning of July 28th 2001, I woke up and knew that something wasn’t right. I walked out of my room and went up to my great-aunt Sarah who was sleeping on an air mattress on the living room floor. “Where’s Dad?” I asked, knowing that he had spent the night at the hospital. “He’s in the shower,” she told me. “Your mom died last night.”

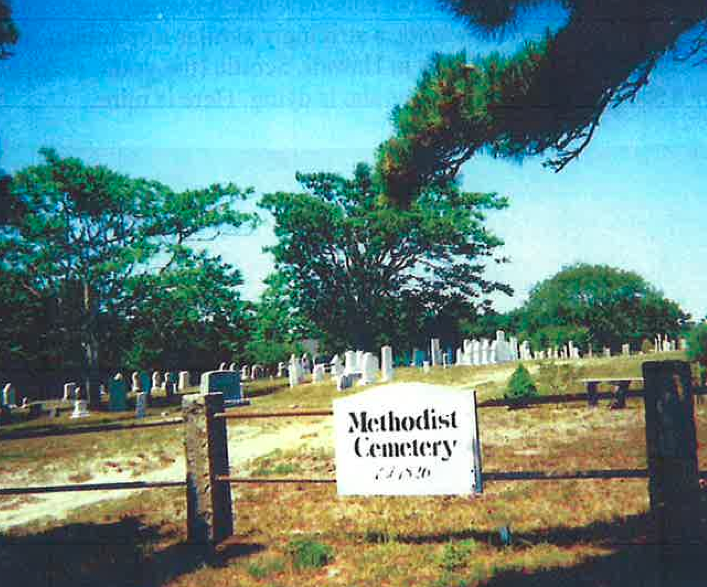

Everyone cried and cried, I cried out of profound sadness but also disbelief. We buried her in Truro on Cape Cod, our summer place. I missed her so, so much, but I couldn’t bear to have anyone see me cry. At the funeral, I tried to hold it in. I preferred the pain of the lump in my throat to the pitying looks from everyone.

The next year, my family went back to Hawaii. We rented the house right next to the little one we rented on Waimea Bay less than two years earlier, back when everything was different. This house was much bigger though, enough to house uncles, aunts, grandparents and cousins. While we were there, we bought a lot of Iz CDs, a famous Hawaiian singer. One song of his, “Starting All Over Again,” became our anthem. We played it everywhere, in the car, in the house; we sang it as we went about. In the intro, he says, “I was scared when I lost my muddah, my faddah, my brothah, my sistah, I was. But no, I guess it’s something so weird, I’m not scared for myself, for dying…because we’re Hawaiian, we live in both worlds. We can relate to this, we live on both sides. It’s kind of like if I went now, that’s alright… we cannot help it bra, it’s in our veins…we cannot help it.” We loved it because he was able to express what we were feeling. Hearing him say it in pidgin sounded so much better than it ever did in English.

When Hawaiians lose someone, they understand it. There’s less blame; they grieve by celebrating the person’s life. My mom was Hawaiian, okay only part-haole, but I cling to that because being in Hawaii, knowing that she is resting in paradise, gives me some comfort. I can go back to her by going back to Hawaii, or just celebrating the spirit of aloha. As I said before, a photo won’t be there to sing to you on your birthdays, and you’d just look stupid if you tried singing to the photo on its birthday. You can’t sit on a photo’s lap, and it won’t stroke your hair or call you Emma Kai-Lou, and tell you that it loves you. I feel Hawaiian and because my mom felt Hawaiian, I’ll always have her. It’s almost as if Iz is telling me that “She’ll be there for the rest of your life. She’ll be there on your birthdays, at Christmastime, when you get your period, when you graduate, have sex, when you marry, have children, when you die. She’ll be there and she won’t be there” (296). Hawaiians are always talking about the spirit of aloha, and I think I finally know what they mean. Aloha means hello, goodbye, and love. It makes everything a lot easier, because it says all I have to say in just three syllables. Hello mom, goodbye mom, I love you: aloha mahuakine.

(Note: All quotations taken from “The Descendants” by Kaui Hart Hemmings, Copyright May 2007 by Random House)