“LOOKS LIKE THE barrel of an old-time machine gun,” Marco said.

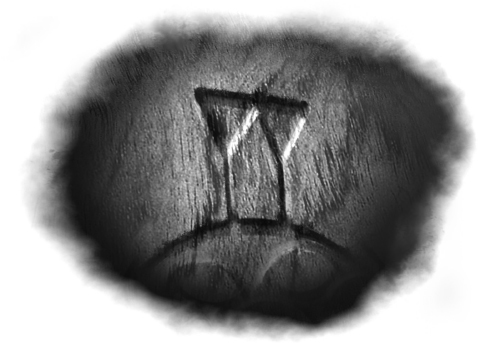

“Or a Heptakiklos with a hat,” Cass remarked.

“A spinning roulette wheel,” Aly said.

My mind was racing. “It could be a code. Think. When we entered the maze at Mount Onyx . . . when we were stuck at the locked door in the underground cavern . . . both times we were able to get in.”

“Because of hints,” Aly said. “Poems.”

“The poems were all about numbers,” Cass pointed out. “Mostly about the number seven.”

Aly grabbed one of the cubes hanging by twine. “There are seven of these things. They look like doorbells.”

She began pulling them, but nothing happened.

“This is a carving, not a poem,” Marco said.

“Yeah, but it’s the Heptakiklos, Marco,” I said. “The Circle of Seven. Seven cubes. Whoever did this knows about the Loculi! It’s got to be in there. I hear the Song.”

I stepped back. It was impossible to think. My brain was clogged with the sound. My ears were pricked for the screeching of the vizzeet, the guards. Where were the guards?

Numbers . . . the patterns of decimals . . .

“Aly, do you remember that weird thing about fractions and decimals?” I said.

She nodded. “Put any number over seven—one-seventh, two-sevenths, five-sevenths, whatever. Turn that into a decimal, and the numbers repeat. The exact same numbers. Over and over.”

“I hate fractions,” Marco said.

“Oot em,” Cass added. (Which he pronounced oot eem—me too.)

I tried to remember the pattern. “Okay, one over seven. That’s one divided by seven. We used that pattern to open a lock.”

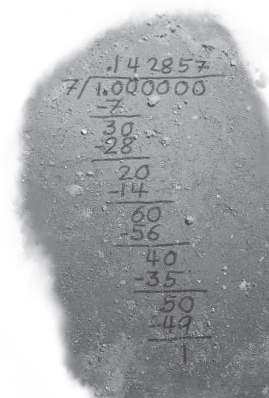

“Torchlight, please. Now.” Cass knelt and began scratching in the sand:

“Dude, you remember how to do long division?” Marco said. “You never got a calculator?”

“Point one-four-two-eight-five-seven!” Cass said. “And if you keep going, you get the same numbers. They just keep repeating.”

“Okay, I’ll do them in order.” Aly immediately yanked on the first cube, then kept going. “One . . . four . . . two . . . eight . . . five . . . seven!”

“Voilà!” Marco said, pulling the handle.

Nothing happened.

In the distance I could hear voices. They were faint but clearly angry. “We’re not going to get out of this alive,” Aly said.

I shook my head. “The guards should have been here already,” I said. “I think they’re afraid. With luck, that’ll give us extra time.”

From under a nearby rock, I saw a sudden movement and jumped back. A giant lizard poked its head out, and then came waddling toward us. Leonard, who had been sitting at the bottom of Cass’s pocket, now jumped out into the soil. “Hey, get back here!” Cass shouted.

As he bent to scoop his pet off the ground, a shadow swooped down toward us.

Zoo-kulululu! Cack! Cack! Cack! Wings flapping, the giant black bird descended to the ground. It landed in the spot where Leonard had been, its talons digging into Cass’s mathematical scratching. With a screech of frustration, it jumped on the Babylonian lizard, missed, and flew away with an echoing cry.

The voices outside the wall stopped. I could hear the guards’ footsteps retreating.

“He ruined my equation,” Cass said, looking at the talon prints in the sand.

Those, my boy, are not bird prints. They’re numbers.

In my mind I saw Bhegad’s impatient face, when he was trying to cram us with info. I looked at the top of the Heptakiklos again:

“That’s not a hat,” I said. “Those are cuneiform numbers. Bhegad tried to get us to study them. But I don’t remember—”

“Ones!” Aly blurted out. “Those shapes are number ones.”

“Okay, there are two of them,” Marco said.

“Two over seven!” I exclaimed. “Two-sevenths!”

Cass quickly wiped away his division and started again:

“The same digits,” Cass said. “In a different order. Like I said.”

Carefully I pulled the second cube. The eighth. The fifth. The seventh. The first. The fourth.

With a loud clonk, the handle swung down, and the door opened.