![]()

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

THE ONES THAT DON’T BELONG

AT 6:00 A.M. my alarm went off at an ungodly volume. Which was just barely loud enough to wake me.

As I rose out of bed, I untied a string from a hook I’d screwed into the wall. The string was part of the pocketful of junk I’d borrowed from the garage. The other end of the string was tied to a wooden hanger—by way of a small pulley hooked into the ceiling. And on the hanger was my shirt. Now the shirt plunged down until its tail just brushed the sheet on my bed.

Not bad.

I took off my pajama top and thrust my arms into the sleeves of the shirt, pulling it off the hanger. Then I slid my body toward the foot of the bed, where my jeans lay waiting. The legs were held open by clothespins attached to two strings I’d hung from the ceiling on hooks. I’d clipped socks to the cuffs of the jeans, and just below the socks I’d left my sneakers open. Super-easy access for all.

Pants…socks…shoes.

I pulled off the clips, tied the shoes, and checked my watch. “Sixteen seconds,” I murmured. I’d have to improve that.

I was not looking forward to another day of Find Jack’s Talent.

Today I was to help the head chef, Brutus, in the kitchen for breakfast. And I had to be on time.

I ran across the compound toward the Comestibule. I passed the athletic center, a sleek glass two-story building with a track, an Olympic-sized pool, indoor basketball courts, weight rooms, and martial arts rooms. Through one of the windows I could see Marco in climbing gear, making his way up a vertical rock wall. It seemed to take no effort at all. I liked him, but I hated him.

Veering toward the back of the octagonal Comestibule, I entered the kitchen. It was enormous, its walls full of white shelves groaning with the weight of flour and sugar sacks, cans of oil and vinegar. Thick doors in the back of the room opened to meat lockers and freezers, blasting cold air every time the doors opened. Kitchen workers were preparing omelets and fruit bowls with blinding speed.

Brutus arrived late, flushed and out of breath. He had a round, doughy face and an impressive stomach. He glared at me as if his lateness was my fault. “Make the biscuits,” he said, gesturing toward a long table jammed with ingredients. “Two hundred. All the ingredients are on the table.”

Two hundred biscuits? I didn’t even know how to make one. “Is there a recipe?” I asked.

“Just leave out the ingredients that don’t belong in a biscuit!” Brutus snapped, scurrying off to yell at someone else.

I gulped. I grabbed a cookie sheet. And I said a prayer.

“I can speak again—the dentist unglued my teeth!” Marco said, bounding into the dorm after breakfast.

I plopped onto my bed in a cloud of pastry flour. I was trying desperately to flush the morning’s biscuit-making experience down my memory toilet.

Except for one thing. One comment by Brutus…

“I think the cinnamon-mint-mushroom combo was…different,” Aly said cheerily, following me into the room.

“They tasted like toothpaste!” Cass added. “But I happen to love the taste of toothpaste.”

I ignored them all, leaning over to take the Wenders rock from my desk drawer. The other three were just noticing the various strings hanging from my ceiling. “You making a marionette show?” Cass asked.

Just leave out the ones that don’t belong…Brutus had said.

I held out the rock. “What if some of the letters are supposed to be left out?” I asked.

“Huh?” said Cass.

“What if this is a code, but not one where you have to substitute a letter?” I pressed on. “What if it’s about taking away letters?”

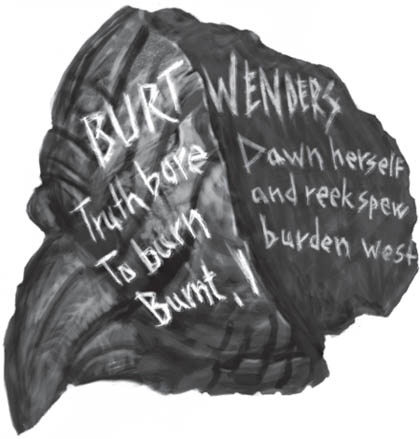

We looked at it again:

I was seeing things in the words, recurring letters. And I had an idea what to do with them.

“Bhegad said this might be a key to the center of Atlantis—whatever that means,” I said. “So maybe Wenders got to the center. Imagine being him. Imagine finding the thing you’ve been looking for, the find of a lifetime—and you think, so what? It’s a hole in the ground. His son, Burt, had died! Think about how he would have felt.”

Marco nodded. “I’d have thrown the key away.”

“Part of him would want to come back announcing, ‘Yo, we found the center!’” I said. “But that would have sent everyone running. It would have been disrespectful to Burt’s memory. So he didn’t do it. Still, Wenders was a professional, one of the best in his field. He had to feel some obligation to the Scholars of Karai. So he made it a little hard. He created a delay, a barrier to prevent people from rushing off to find the fissure.”

Marco was staring oddly at me. “What made you think of all this? It’s like you’re reading the guy’s mind.”

I shrugged. I didn’t know. The feeling was blindsiding me. “This was before the discovery of G7W, before the treatments,” I said. “It must have felt to Wenders like a part of himself had been ripped away. So maybe he meant for the name Burt Wenders to be taken from the words of the poem—the way the kid was taken from him.”

“Let’s try it,” Cass said.

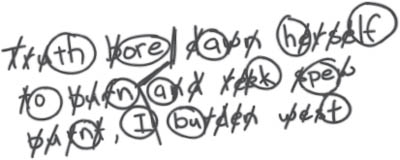

I began writing the words of the poem on a sheet of paper. “Cass, you said something about the shape of the lines. It’s like they’re in two columns. And on top of them, there are the two words of the son’s name.”

“So maybe take the word Burt from each line in the first column and Wenders from the second?” Cass asked.

Exactly.

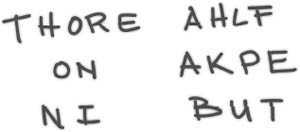

Then I wrote out the remaining letters:

“Looks Greek to me,” Marco said. “Maybe Swedish.”

I exhaled. I was ready to crumple up the paper and toss it, when I looked at the bottom two lines. The word on began the second row. And the third began with ni, which could easily be in.

“I think they’re just scrambled, that’s all,” I said.

I smoothed out the paper and carefully began writing.

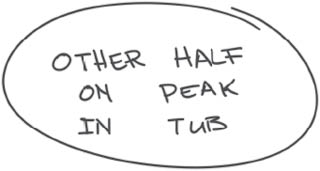

“On peak!” Aly shouted. “That could be Mount Onyx! Maybe that’s where we’ll find the other half of this rock.”

Marco scrunched up his brow. “So all we have to do is find…a tub? On the top of a humongous mountain?”

“Maybe that part is a mistake,” Cass suggested. “Or maybe it’s supposed to be but, not tub.”

“In but?” Marco said. “That scares me.”

Cass shrugged. “An alternate spelling for butte?”

“That scares me less,” Marco said.

“Tomorrow,” I said, folding the paper and putting it in my pocket, “we will find out.”