CANAVAR WAS SMALL, but his drool loomed closer and packed a world of disgust. “Could you please get off me?” I said.

“I know what thou thinkest.” Canavar leaped off, his drool landing with a tiny splat about two inches from my ear. “Gnome! Pixie! Troll!”

“I wasn’t thinking that at all!” I protested.

“Ha! My form may be crooked, but I am fast and strong,” he crowed. “Thieves and cutpurses do well to fear such as I! But seeing as thou art young and inexperienced—well, a majority of thou—I will let thee go quietly.”

“Please,” I said. “If you have anything to do with this museum—”

“Anything to do?” He waddled over to the dropped stone, scooping it from the ground. “I am resident archaeologist, cryptologist, oceanologist, DJ!”

“DJ?” Cass asked.

“Doctor of jurisprudence!” Canavar replied. His face grew somber. “But, being of an appearance and temperament not suited for the general public, I prefer working after hours. Of which these are. Now go, or I shall trap thee overnight and cast thee tomorrow before the arbiters of civic judgment!”

“I think he means report us to the authorities,” Cass said.

I thought quickly. “We need to look around a little,” I said, standing up. “We brought a man here from very far away, a great archaeologist who is ailing badly. It’s his . . . dying wish.”

Canavar’s eyes darted toward the van, where Dr. Bradley and Professor Bhegad were waiting. He waddled closer, peering into the window. “By the ghost of Mausolus,” Canavar breathed, “is that . . . Raddy?”

“I beg your pardon?” Professor Bhegad said.

“Pardon granted!” Canavar said. “Raddy—thy nickname at Oxford amongst thy admirers. You are Radamanthus Bhegad, Sultan of Scholars, Archduke of Archaeologists, yes? What on earth has befallen thee? And what can I do? Canavar, thy acolyte, at thy service!”

Dr. Bradley and Professor Bhegad stared at the misshapen man. For a moment neither knew what to say.

“Yes, yes, I am Bhegad,” the professor said, his voice soft and weak. “And, um . . . yes, indeed, there is something you can do. For the sake of archaeology. These people . . . must have full access. To . . . er, everything you know about the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.”

Canavar stood to full height, which wasn’t terribly impressive. “Oh, by the warts on Artemisia’s delicate nose . . . I suppose I have a job to do now. I do, yes? Then come.”

He sprang away from the van and skipped back the way we’d come, disappearing around the side of the castle. But we stood rooted to the ground, stunned.

“My mother told me not to believe in leprechauns,” Aly murmured.

“But for this,” I said, “we make an exception.”

“By the blessing of Asclepius, what a tale!” Canavar exclaimed as he sat before a pile of rocks on the ground. “So thou seekest a sort of . . . sphere of salubrity? Is that what thou sayest?”

Cass gave me a look. “Did we sayest that?”

“I think he means a Loculus of Healing,” I said. “Look, Canavar—”

“Dr. Canavar,” Canavar said.

“Dr. Canavar. The organization I’ve been telling you about—Professor Bhegad’s group, the Karai Institute—we believe the relic was hidden within the Mausoleum.”

“Oh, dear,” Canavar replied, his brow furrowing, “then by now ’twould be presumably reduced to rubble. Cannibalized to construction. Stolen. Sunken undersea.” He gestured toward the castle. “Behold, this is what is left of your Mausoleum! Stones ground into dust. Dust reformed into brick. A bas-relief here, a statuette there. All to build this . . . abomination! This monument to knightly ego! Oh, misfortune!”

He was starting to cry, his tears dripping on the collection of stones he was arranging. Cass and Aly looked at me helplessly.

I stood and began walking around the yard. Where was the Song of the Heptakiklos? I had felt it outside the labyrinth of Mount Onyx, the Massarene monastery in Rhodes, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. I should have been feeling it now.

But all I felt was a vague warmth from the rocks. Was that a hint of a lost Loculus? Was this one hopelessly spread out in the mortar and stones of the castle?

“Canavar,” I said.

“Dr. Canavar.”

“Right. So, some of the Mausoleum stones were all ground up. But is it possible others were taken away? Are there parts of the Mausoleum in other places besides here?”

“This site was paradise for thieves,” Canavar said. “Some escaped—well, mostly those that came by land. Some sold their stolen stones and jewels on the open market. But the largest thefts, my boy, came by sea. These were men of equal parts stupidity and fearlessness. And thou hast little chance of finding their booty.”

“Their booty?” Cass said.

“Pirate booty,” Aly explained. “Stolen treasures.”

Canavar gestured toward the sea. “The sea bottom is littered with shipwrecks containing pieces of the Mausoleum still within their holds. The sand and coral are nourished with the bodies of those who scoffed at Artemisia’s Curse.”

“Artemisia,” Aly said. “That was the wife of the ruler, Mausolus.”

Canavar nodded. “Also his sister.”

“Isn’t that illegal?” Cass said. “Or at least incredibly gross?”

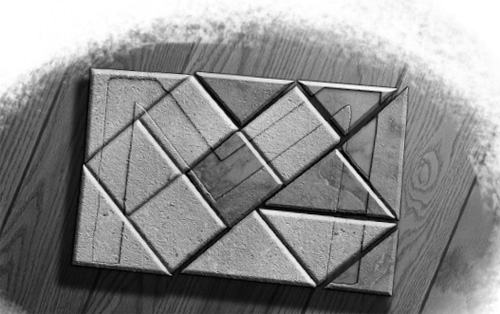

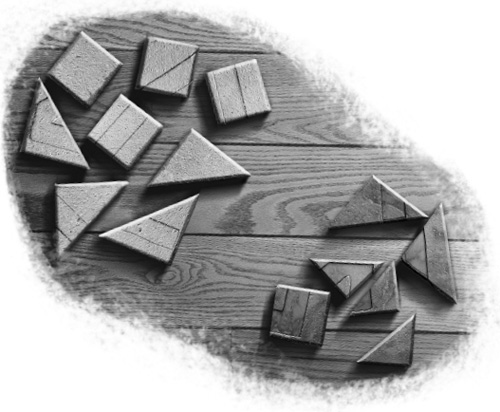

“The world was a different place.” Canavar bowed his head. “I present to you the most important recent Mausoleum find. The rocks before thee were salvaged by the hands of a heroic, prodigiously skilled sea diver. Namely, me. This is my life’s work—to find all there is. To bring them back. If they came from the Mausoleum, they must be returned. It is where they belong. It is where they have their life. Their meaning.”

I knelt by the stones. They were small, none more than four or five inches long, all of them in sharply cut geometric shapes. Some seemed new, others worn and ancient, and some were etched with straight lines.

Canavar’s tiny features expanded with pride. “You see the etched lines on the stones? I believe they formed a kind of symbol, or logo. The Greek letter mu, equivalent to our M, for Mausolus.”

“But this place was Persian back then,” I said, trying to dredge up my research. “Not Greek.”

Canavar nodded. “The Persian kingdom of Caria. But as a port, Caria was home to many nationalities. Mausolus was allowed to be an independent and flexible ruler. He hired Greek architects and Greek sculptors. Hence the Greek M. Wouldst thou like to see how the stones fit together?”

He quickly organized the stones with his spindly fingers.

“Ergo, an M!” Canavar said.

I nodded. “Some of these are lighter in color than the others.”

“Yes. Those were the ones I salvaged from the ship. I studied these stones for years, wondering what they meant. I positioned and repositioned them until I saw, in my mind’s eye, the possibility of this M, even though the other stones were missing. So I carved new ones, to represent them. To fill in the blanks, as it were. Those are the darker stones. It was the material I had.”

“Wait, you made it up?” Cass asked. “You had a bunch of lines and just assumed it was an M? What if it was something else?”

Canavar glared at him. “Thinkest thou perhaps Q would be appropriate for Mausolus?”

He turned in a huff and stomped away toward Torquin and Dad.

Cass, Aly, and I squatted by the stones. I touched them one by one. “They’re warm,” I said. “Just the old ones. Not the new.”

“They all feel the same to me,” Cass said.

“Don’t they seem kind of small?” Aly held one up, turning it around in her hand. “I mean, think about the carved letters over the columns of the House of Wenders—they’re huge. Imagine this thing at the top of the Mausoleum. No one would see it.”

I pressed my hand to one of the stones and kept it there. I could feel my palm tingling. Now Aly and Cass were both looking at me.

“These stones are different.” I carefully separated the rocks, older on the left, newer on the right.

“I’m feeling something,” I said. “From the lighter-colored ones, the older stones. It’s not like the Song. But it’s something.”

“Walk one of them around,” Aly said. “Maybe it’s like a Geiger counter. It’ll start singing to you when you’re near a Loculus.”

I picked up a stone and began pacing through the yard, circling closer to the gate and then back toward the cliff.

“Young fellow, seekest thou a men’s room?” Canavar’s voice called out.

“No, I’m good.” I stared out over the coastline to the west. I pictured the ships of the Knights of St. Peter with sails unfurled. Over the bounding main. Whatever that meant. I imagined the holds filled with great statues and polished stones . . .

If they came from the Mausoleum, they must be returned. It is where they belong. It is where they have their life. Their meaning.

I turned and walked toward Canavar. He was deep in conversation with Dad and Torquin now. “Canavar—” I said.

“Dr. Canavar,” he corrected me again.

“Dr. Canavar. I have a big, big favor to ask you. Can we take your stones to the location of the Mausoleum?”

“But we were already there,” Cass whispered. “You said you didn’t feel anything at all!”

“I want to try again,” I said. “With these stones.”

Canavar looked from Dad to Torquin and chuckled. “Ah, children do love rocks, don’t they? And children, no matter how many times they are told, do not comprehend the value of antiquities. Mr. McKinley, thou wilt, of course, properly discipline thy offspring and restrain him from acts of cultural disrespect.”

“Excuse me?” Dad said.

Canavar turned away and sidled back toward the rocks. “Thou art most cordially excused. Good night.”

Dad looked at Torquin. With an understanding nod, Torquin lumbered past Canavar and scooped up the pile of rocks with two swipes of his massive paws.

“I—I beg thy pardon—” Canavar stammered. “Is this some sort of jest?”

Torquin shoved the rocks into his pack, then grabbed Canavar’s collar and lifted him off the ground. “Torquin love rocks, too.”