Opening any dramatic work takes art and verve, or you lose your audience. The exposition (background or scene-setting information) is part of the opening contract you offer your audience. This implies a promise by the maker to the audience about the film’s purview, style, and purpose. It tries to set up the world of its central characters as economically and appealingly as possible. At this book’s website www.directingthedocumentary.com you can run 12 minutes from Legacy (USA, 2000) and Omar and Pete (USA, 2005), two documentaries by the Academy Award nominee Tod Lending, and see how each implies its purview and intentions. You can also see four 5-minute student documentaries in their entirety.

Whether an audience goes on watching your film depends on how you set up its dramatic purview, and how attractive it finds the discourse you mean to use. I see three main types:

Propaganda: Wants the audience to buy the premise and produces only the evidence to support a predetermined conclusion.

Binary: Likes to give “equal coverage to both sides,” as if truth is like a coin which only has two sides, while remaining neutral and shadowy as a narrative voice. Sees the audience paternalistically as empty vessels that need filling.

Dialogical: Sees the audience-member as willing to sift through contradictions and make thoughtful judgments. Aims neither to condition nor distract the viewer but to share the contradictions and mystery of real human situations whose outcome may remain unknown.

Only the last treats its audience as mature equals, so how you signal your film’s language as well as its nature and purpose within the first minute will matter greatly. Like a restaurant handing out an inviting menu as customers arrive, the astute storyteller sets terms in the opening moments that make the audience anticipate something worthwhile.

How much should you lay out? How much factual material can the audience absorb before meeting the characters and absorbing their predicament? Should you start the action (a lesson, an arrest, or, in the case of Legacy, a death) to give momentum during the initial exposition of the film? How much information should you hold back to enhance dramatic tension? What kind of evidence should the audience expect?

The answers to these questions can never be standardized; they emerge from the experience of watching each film on its own terms.

The reality everyone can point to, agree on, and defend in court is what the documentary theorist Bill Nichols calls historical reality. Films about political or scientific subjects fall into this camp, though facts and other evidence can be contradictory—and even more interesting because of it. No less real, and a lot harder to convey, is what people think, feel, fear, hope for, or dream about—which is their inner, subjective reality. This, especially when it involves extreme situations, can be fascinating.

Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir (Israel, 2008, Figure 4-1) is an animated documentary that developed from a recurring dream of the director’s. It arose from emotional trauma during the 1982 assault on Beirut, in which the director participated as a 19-year-old soldier. Now Folman contacts friends one by one to ask about their nightmares and lost memories. He uses a form of animation invented by his group which greatly helps the film achieve its dreamlike intensity. At the core of his friends’ faulty recall is the massacre of over 700 refugee Palestinians, mostly women and children, at the refugee camp of Shatila, near Beirut. Though perpetrated by a Lebanese Christian militia, it happened under the eyes of Israeli Defence Forces, including Folman’s friends. The experience has left an indelible stain of guilt that numbs these former boy soldiers, and leaves them with recurring nightmares. The last 10 minutes of the film leave you overwhelmed with sorrow for humankind.

Because the camera is a mechanical recording device, people often assume the documentary is objective. But can a camera really record anything objectively? What, for instance, is an objective camera position, when someone must decide where to place the camera? How can you turn a camera on and off objectively, or decide objectively what to select from your recorded material? Closely examined, every step in filmmaking takes judgment and subjective decisions.

It is true that much news reporting and some documentaries—particularly older ones—appear objective because they balance opposing points of view. So-called “balanced reporting” is an old newspaper strategy developed to evade charges of political bias. It is a strategy that can fail its readership in spectacular ways. Reputable British newspapers in the late 1930s depicted the trouble brewing in Germany as a contemptible squabble between equally culpable Communists and Nazis. In the war that followed, millions lost their lives, and Britain was dangerously unprepared to defend itself since the mainstream press had failed to foresee what had been building.

The “balanced perspective” is a convenient posture that lets journalists present the opinions and judgments of others in a false counterpoise. It makes a convenient cover for conditioning the reader. When reporting, however, leads to preordained conclusions, it becomes the convergent information of propaganda, which aims to indoctrinate rather than open its audience to the open-ended complexities of real-life issues. Robert Greenwald’s Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism (USA, 2004, Figure 4-2) levels this charge to great effect against the Fox News Channel, which likes to advertise itself as “fair and balanced.”

If you cannot be objective, you can be fair. That means not stacking the evidence and including evidence that may be contradictory. If your film is about a medical malpractice accusation, for instance, it would be prudent to give careful, sympathetic coverage to the allegations of both surgeon and aggrieved patient.

Like any good journalist or detective, the documentarian crosschecks everything independently verifiable, since people and their issues are seldom what they seem. The accused is not always guilty, the accuser not always innocent, and the bystander is not always disinterested. Counterpoising opinions and impressions helps protect your interests by acknowledging that most truth is complex, and one can only assess it like a juror—in the light of human experience.

There is good reason for this cautiousness. Films that say something make enemies, so you must be ready to defend your work—possibly in court. If they find a single error, your opponents will use it to destroy your credibility. Michael Moore’s critics took some questionable chronology in his first film, Roger and Me (USA, 1989) and did their utmost to discredit him. Documentary must often lead its audience through a maze of conflicting facts and evidence, so that audiences can arrive at their own conclusions. Interestingly enough, this is how courts put evidence before a jury of ordinary people— still, after thousands of years, the preferred test of truth in a democracy.

The modern documentary differs from its earlier, more scripted and premeditated forms whose clumsy technology required the action to be choreographed for the camera. Earlier audiences were more trusting of authority and more ready to accept what they were told, but today’s audiences have learned to be skeptical. Happily, light and mobile equipment allows you to record events as they unfold, so we are accustomed to seeing people dealing spontaneously with heightened moments in their lives. As we watch, we make character and motive judgments much as we do in life.

In Nicholas Broomfield and Joan Churchill’s Soldier Girls (UK, 1981, Figure 4-3), we see how the US Army trains its women soldiers. Through formal and informal moments, including sadistic training and ritual humiliations, we come to question some of the army’s most basic assumptions. How is it, we ask, that authoritarian white male sergeants are allowed to routinely humiliate black or Hispanic female recruits?

The film delays confronting a central paradox: warfare is brutal and unfair, so caring instructors cannot kindly train soldiers of either gender to survive. However, the army’s arguments wear thin after what we have seen, and leave us disturbed by larger questions about military traditions and training—just as the film’s makers intended. Though we share what moved or disturbed Broomfield and Churchill, they never tell us what to feel or think. Instead, by exposing us to contradictory and provocative evidence they draw us into realization and inner debate. We become a jury arbitrating not right versus wrong—which is easy to decide—but right versus right, which is not. Humanity’s more interesting problems are usually of this order.

You cannot show events themselves, only a construct of selected shots and viewpoints that sketch in the key facts, action, and emphases—all subjectively determined by you, the filmmaker. Doing it fairly will face you with ethical dilemmas over which you will sometimes lose sleep. But if your film can show a broad factual grasp of its subject, evidence that is persuasive and self-evidently reliable, and the courage and insight to make interpretive judgments, then it is worthy of our trust. That is the best anyone can do.

A good documentary is a drama drawn from lived reality, with all its moral and social implications made visible by the enhancement of astute storytelling. Analyze most documentaries, and they have dramatic ingredients similar to fiction stories. That is, they contain characters, situations, pressures, choice, conflict, tests, reconciliation—everything we are used to seeing in drama.

Your documentary must reveal characters and their situations; show what is at issue, and what the central characters are trying to get, do, or accomplish. To satisfy your audience you will probably have to reveal the obstacles that prevent them, one by one, and ultimately include a confrontation between the forces in conflict. You will need to show how the ultimate conflict is resolved and what the consequences are. Include all these, and you will entertain your audience members and exercise their judgment to the full.

Transparent documentary tries to create the feeling that you are seeing unmediated reality, but close analysis soon reveals that though the illusion may be skillfully sustained, it does so by using proven fictional techniques of juxtaposed shots and artfully compressed time and space. We have said that documentaries, like the fiction films they resemble, are authored constructs. There is nothing inherently dishonest in this: they are directors’ attempts to pass over the spirit of truth, rather than its letter.

Each film is a vehicle—conscious or otherwise—for the values of its makers. How and why the director tells the tale proceeds from convictions that you draft in the working hypothesis. This merely states, formally and concisely, intentions you might otherwise carry out less thoroughly and consciously by instinct.

The simple fact is that, as a purposeful entertainer, you make a film in order to act upon your audience, and your film is a bridge connecting your audience to your chosen “corner of nature” by way of your “temperament.”

Think of those you have known longest and best—your parents, perhaps. Try naming their long-term, major conflicts. Easy, or difficult? Everyone is engaged in struggle of some kind, but few know their own deepest goals and demons. As a documentary author, you must be able to see them in those around you. Particularly when you plan a character-driven story, you must press yourself to define, as best you can, what your central character is trying to get, do, or accomplish, and therefore what obstacles block his or her path. As you learn ever more about your characters, revise and refine these judgments, for they strongly influence what story you can tell, what issues are at stake, and what you can do as a storyteller to structure and maintain dramatic tension.

Your main job as a director is to characterize what your central character is really striving for—short term and long term. This is the secret to vibrant storytelling, and though it sounds simple, its implementation is not. Your research will demand penetrating and dedicated observation, and much careful thought as to how to show what you find.

All stories can be preliminarily divided into two kinds: one is energized by a character or characters, the other takes its energy from predominating events. To decide which you are dealing with, simply decide the source of the film’s driving energy. A film about the effect of a tornado on a sleepy little town would be a plot-driven story because its energy comes from a huge, life-changing event that affects many people and in many different ways. They are the puppets of Fate.

Other stories may be character-driven, since life is full of strange and wonderful personalities. If you are intrigued by the saying, “character is fate,” you will see how often people enact events that, quite unconsciously, they have made happen. Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man (USA, 2005, Figure 4-4) tells the story of Timothy Treadwell’s life and death using his own footage of the wild bears that he loved and unwisely trusted—until they literally ate him. Errol Morris’s The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (USA, 2003, Figure 4-5) is another character-driven film in which the former US secretary of defense tells, in his own unreliable words, how he was a hawk during the Vietnam War but later heard his conscience and now shares the anti-war position.

FIGURE 4-4

Grizzly Man, a cautionary tale about a man who thinks bears reciprocate his feelings for them. (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection/Discovery Docs.)

FIGURE 4-5

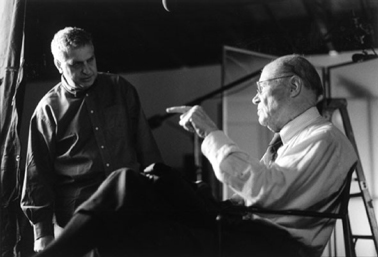

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara. (Photo courtesy of Fourth Floor Productions.)

In life, everyone pushes against obstacles while trying to realize their needs and goals. Often these are none too visible to themselves or to anyone else. McNamara in Fog of War is the high government official who wants to get on the right side of history. He tells us he was deluded into supporting policies that killed thousands during the Vietnam War. The film is a chilling character study, since it shows someone who supported government policies that killed thousands, and who now tries to justify what he did while seeking public absolution. Its dramatic tension lies in watching a man struggle to rescue his place in history. His main conflict appears to be the fear of going down in history as evil when he wants to be seen as good.

In a world convulsed with evil and pain, many stories are designed to tell the grim truth while nonetheless leaving us with a little hope. If we see nobody learn something and grow, even just a little, then their struggles give us that all-too-familiar mood of despondency and resentment. Because this discourages us from taking any action ourselves, many tales try to incorporate development, or growth in the central character, no matter how minimal and symbolic.

When you work at an idea for a documentary, it will be important to predict who or what is likely to develop during your film’s time span. Can the son break away from the father? Will the rain finally come and answer the farm cooperative’s prayers? Can the immigrant couple learn enough of the new language to find employment? Will the child learn the identity of her father from her mother (Figure 4-6)? What sustenance, what hope, what truths can the audience draw from any of the likely changes?

FIGURE 4-6

The mother who won’t reveal her daughter’s paternity in The German Secret.

It has been said that “a documentary film is shot with three cameras: 1) the camera in the technical sense; 2) the filmmaker’s mind; and 3) the generic patterns of the documentary film, which are founded on the expectations of the audience that patronizes it.”1 This third “camera” refers to the audience’s frame of mind as they interpret the film according to the culture of film as they know it.

You hope to use the film medium justly and persuasively, and for your audience to understand what you mean. Historically, television documentary has favored monological discourse, that is, actuality delivered in a linear way by specialists and authority figures who interpret, assign meanings, and signal what’s important to the rest of us. Except for specialized nature and science films, audiences have grown to distrust this relationship, so that many documentaries now use a dialogical discourse—that is, voices in conversation with each other, multiple voices spinning a tapestry of diverse impressions and opinions. Dialogical films, rejecting the stance of settled, paternalistic lecture, opt to reveal instead a more charged, conflicted, and multifaceted reality.

Viewers actively assess these conflicting impressions, perceptions, and voices against their own knowledge of life. Under extreme conditions, human perception turns surreal and hallucinatory, as you see so memorably in Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (USA, 1988, Figure 4-7). Exceptional documentaries convey not just the outward, historical reality of those they film, but also a strong sense of the way that outward actions come from inner conflict.

Our thoughts, memories, dreams, and nightmares should also count as actuality since they are the interior dimension of outward actions. Writers have always been able to portray interior realities, sometimes including the storyteller’s perceptions as part of the narrative. At a certain point in John Fowles’ postmodern novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman, the narrator wryly admits he has lost control of his characters, and gets into a Victorian train to brood on his main character Charles sitting across the carriage. Film, the newborn among the arts family, is gradually learning to claim such imaginative freedoms.

Today’s documentaries use every imaginable storytelling method to hold our attention: they can magnify a tiny backwater, explore intimate and unlikely relationships, chronicle large historical events, or rattle the teeth of a nation by speaking truth to power. Whatever you intend for your audience, the medium is also part of the message, and only by doubting how that message arrives, and testing exhaustively what impressions your film actually conveys, can you be confident that your construct ultimately delivers all you intended. The more intricate the issues, the more work it will take to strike a balance between clarity and simplicity on the one hand, and fidelity to the murkiness and complexities of actual life on the other.

FIGURE 4-7

Under extreme conditions, human perception turns surreal and hallucinatory, as in The Thin Blue Line.

A documentary’s form is the way a film presents its story, and this usually hinges partly on the need to maintain dramatic tension, but on clarity and practicality too. With the architect Louis Sullivan’s famous advice in mind, “Form follows function,” decide how you want to act upon your audience. Your film’s life-materials strongly determine your film’s form, but what you are trying to accomplish should order and organize its form too.

How best to handle time often leads you to your film’s most effective form, and this helps us decide whose particular stream of consciousness the film wants us to share. A film may present time chronologically, in retrograde motion, or as a set of imperfectly grasped, randomly accruing memories, as in Waltz with Bashir mentioned earlier. Its viewpoint may belong to the storyteller, the narrator, one of the participants, or to someone else more peripheral.

Style refers to visual and other characteristics that let us relate a film to works like it—whether by the same director, or by others working in the same period, “school,” or subject matter. This is because every work of art or science grows out of all the others that preceded it. “If I have seen further,” wrote Isaac Newton to a colleague, “it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”2 A film’s references are full of particular language and precedent that the audience can place in our common film and cultural vocabulary.

Form and style are thus closely related, and can together produce a film that is controlled and premeditated, spontaneous and unpredictable, lyrical and impressionistic, starkly observational, satirical, or even farcical. A documentary can use commentary or no speech at all, interrogate or ambush its subjects, catalyze change, or muse aloud about its own unsatisfactory progress. It can narrate using words, images, music, or human behavior. It can employ literary, theatrical, or oral traditions and borrow from painting, music, song, essay, or choreography.

For examples of inventive form and style, look to the other arts. Film is cousin to them all. Your task will always be to find a form and a style uniquely suited to your film’s purpose, and your ability to do this will set you apart like nothing else.

Since the great challenge in making documentary is to tell a story visually, rather than fitting pictures to a narration, why not make your own silent film? That is, one that can have music and inter-titles, but no diagetic sound (sound that is inherent to the situation being filmed). Music that you add would be non-diagetic because it has been added authorially and the characters in your film cannot hear it. Try SP-4 Flaherty-style Film which allows you to choreograph your cast as if shooting fiction, or SP-5 Vertov-style Film which builds its action and atmosphere by montage (action shots cut together to supply information, and build atmosphere and process).

1. Trinh T. Minh-ha, “The Totalizing Quest of Meaning,” in Michael Renov, ed., Theorizing Documentary (Routledge, 1993), p. 98.

2. Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), English physicist and mathematician.