FIGURE 15-1

While a choir serenades the GM chairman in Roger and Me, the sheriff evicts his laid off workers.

Documentaries are largely created through intelligent editing, an alchemy that works magic and miracles. Few understand this until they take its long, exploratory journey for themselves.

Editing techniques are hard to grasp from a book, but you can see their results from films you admire. Work out for yourself how editing suggests eyes, ears, and the warmth of human intelligence working together, all guiding your attention toward hidden meanings. This elevated state is seldom even visible in early cuts of most documentaries. More often you seem stuck with a hopeless cause. Do not despair. The curse of the first assembly is its length and slowness, and we need to look at techniques that will move the story along faster.

Cutting from action to action, or sequence to sequence, parallels the way we mentally register our movement through a day, a vacation, or a visit to a new town. This principle called elision has the same effect as a photo album in which the owner has made a construct by compressing the essence of a wedding or holiday into a photomontage.

If you are cutting from event to event, see if you can remove the front and end of each sequence, retaining only the heart of what counts in the emerging narrative. Try to enter the sequence when it is already in action, and leave before it concludes. The test is to ask whether the audience can (a) imagine how the sequence began and thus not need to see it, and (b) imagine how the sequence will end, and therefore need not see that either. Cutting from a man eating breakfast at home to him at the wheel of a truck is a way to elide (shorten) all the unimportant material and show only his relations with his family and what he does for a living.

The breakfast can be compressed to essentials too. If you have handheld coverage of the whole 30-minute meal, and have moved the camera from angle to angle, you might only want to show that he has a wife and two daughters, is a fond parent who jokes with his children, and a husband who does the cooking. This you can do in perhaps four or five shots lasting a minute. Cut to interior truck!

Much of human activity is repetitive, and if you shoot the breakfast in different angles and different-sized shots, you will find coffee pouring in wide shot and coffee pouring in a close shot. You can bridge the two shots together, and eliminate some time, providing:

● The action and settings match between the shots (both girls are still in their chairs).

● There is a good difference between the shots in size and/or in angle.

● You have a defined movement (beginning to pour coffee, say) to act as the bridging action between the two shots.

The perfect moment to make a match cut always comes at the psychological moment when the spectator mentally identifies the action to come:

● You see a coffee pot lifted and see it just begin tilting (ah, he’s pouring coffee).

● You see someone cross a room, turn, and just begin bending their legs (ah, she’s sitting down).

● You see a boxer stumble, turn, draw back his right arm, and just begin a thrust (ah, he’s going for the other guy’s jaw).

The precise moment when the action’s purpose becomes evident is the precise moment to cut and complete the expected action in the new shot, whether it goes long to close shot, or close to long shot. Because the eye does not register a new shot’s first frames, you must repeat the action by two–three frames if the action is to appear continuous. If instead you scientifically match the action, it will look jerky, as though frames are missing from the incoming shot. Try it for yourself.

So the match-cut rule is: Let the action initiate (that is, until we just recognize what’s coming), then complete the action in the new shot. Repeat some frames in the incoming action to make the action across the cut appear smoothly continuous.

When a continuous shot has a stretch of time cut out, we call it a jump cut. If you cut from a kid first in his underwear, then wearing shirt, then adding pants, and finally a winter jacket all in the same shot, you have dressed your kid in three jump cuts for a winter journey to school, and the whole thing happens in a sprightly 10 seconds. For this we have the TV commercial to thank.

You can also use your editing software to complement the narrative by showing an action in fast or slow motion. Use fast motion to humorously speed up the banal, and slow motion to show us something significant in detail, such as a humming bird approaching a flower, or a train derailing on a bend. Again, these modes parallel the way our attention waxes and wanes according to the significance or otherwise of the action.

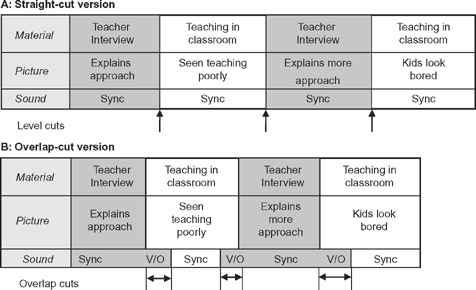

A useful way to abridge time is to take two simultaneous activities and cut back and forth between the two storylines, paring each down to essence by intercutting. In Roger and Me (USA, 1989) Michael Moore famously intercuts the GM choir singing sycophantically to chairman Roger Smith, “Santa Claus is coming to town,” while a sheriff disconsolately evicts a former GM worker’s family. Smith reads from Dickens’ Christmas Carol while the sheriff’s men pile the family’s pathetic goods on the sidewalk, including their Christmas tree (Figure 15-1). It is a heartbreaking, maddening comparison, and Roger Ebert is right to call the film a revenge comedy.

FIGURE 15-1

While a choir serenades the GM chairman in Roger and Me, the sheriff evicts his laid off workers.

If you want a series of cuts to hit the beat of a jazz piece, or to happen on the rhythmic sounds of someone using an axe, you must position the cuts two–three frames before the actual “beat” frame. This is because human vision takes about 1/8th of a second to register a new image.

After running your first assembly two or three times, it seems like clunky blocks of material with no flow. First you may have some illustrative stuff, then several blocks of interview, then a montage of shots, then another block of something else, and so on. Sequences go past like floats in a parade, each separate from its fellows. How to orchestrate sound and action, and create the effortless flow seen in other people’s films?

This often means bringing together the sound from one shot with the image from another, but you cannot really work out counterpoint editing in a paper edit since it depends too much on the nuances of the material, but you can easily decide which materials should intercut well. The specifics emerge from the materials themselves, as we shall see when we come to overlap cutting.

Notice that a demanding texture of word and image places the spectator in a more critical relationship to the “evidence.” It expects an active rather than passive participation, and the implied contract is not to sit and be instructed, but to interpret and weigh what you see and hear. Sometimes the film uses action to illustrate, other times to contradict, what has seemed true. The teacher is a good man, but also an unreliable narrator whose words you cannot take at face value. However, whatever makes someone an unreliable narrator is going to be something intriguingly human.

There are other ways to stimulate the audience’s imagination through changing the conventional coupling of sound and picture. For instance, in a street shot you might show a young couple we presume are lovers go into a café. They sit at a window table, but the camera remains outside near an elderly couple discussing the price of fish. The camera moves in close to show the couple talking affectionately to each other, but what we hear is the older couple bemoaning the price of cod. The result is ironic: in two states of intimacy, we see courtship, but hear the concerns of later life. With great economy of means, and not a little humor, a cynical idea about marriage is set afloat—one that the film might go on to dispel with more hopeful alternatives.

By juxtaposing materials and demanding that the audience interpret them, film can counterpoint antithetical ideas and moods, and kindle the audience’s involvement with the dialectical nature of life itself.

A very useful editing trick is to change straight cuts (sound and picture cutting at the same moment) to overlap cuts (sound and picture cuts each staggered for a particular reason or effect). This mimics something we do all the time unawares.

In life, if you notice, we often probe our surroundings mono-directionally (eyes and ears directed at the same information source) and sometimes bi-directionally (eyes and ears directed at different sources—watching a bird high in the air while hearing kids shrieking in a nearby swimming pool, say).

Our attention can also move about in imaginary time—forward (anticipation and imagination) or backward (memory). Look for these facets particularly in fiction films you like, and you will see how the editing functions to suggest eyes, ears, and intelligence working together. As such, they form the kind of probing coalition our eyes, ears, and intelligence use to extract meaning from layers of impression. The overlap cut is an important editing technique because you can use it to suggest the shift of mono- or bi-directional attention, especially in dialogue sequences.

The overlap cut (aka lap cut or L cut) breaks the level-cut convention (sound and picture cut at the same moment) by bringing in sound ahead of picture, or picture ahead of sound. If, say, you set out to show that a likeable teacher has a superb theory but a poor teaching performance, you would shoot two sets of materials, one of him describing how he teaches, and the other of him droning away in class. Editing these materials in juxtaposition, one uses the conservative, firstassembly method that alternates segments as in Figure 15-2A: a block of the man explaining his ideas, then a block of teaching, then another block of explanation, then another of teaching, and so on until you’ve made the point with a sledgehammer. When technique and message become predictable, the audience tunes out.

Imagine instead integrating the two sets of materials, as in Figure 15-2B. The teacher begins to describe his philosophy of teaching. He is a nice man, and while he speaks, we cut to the classroom sequence with its sound low and the teacher’s explanation continuing over it (this is called voice-over, abbreviated as VO). When the voice has finished its sentence, we bring up the sound of the classroom sequence and play the classroom at full level. Then we lower the classroom atmosphere and bring in the teacher’s interview voice again. At the end of the classroom action, as the teacher gets interesting, we cut to him in sync (that means including his picture to go with his voice). At the end of the third block we continue his voice, but cut—in picture only—back to the classroom, where we see the bored and mystified kids of Block 4.

FIGURE 15-2

In A, the first-assembly method of alternating segments. In B the two sets of materials have been edited in counterpoint.

Now, instead of having description and practice in separate blocks of material, you lay description against practice, ideas against reality, in a harder-hitting counterpoint that demands interpretation by the audience. There are multiple benefits: the total sequence is shorter and sprightlier; talking-head material has been pared to a minimum; and the behavioral material—the classroom evidence against which we measure the teacher’s sense of himself—is now in the majority.

In dialogue exchanges the lap cut circumvents the jarring effect of the level cut, and mimics the way our eyes and ears move around, separately detecting packages of information for our brain to synthesize.

Usually L cuts are a refinement of later editing, but we need a guiding theory. Think of how our ever-reliable model for editing—human consciousness—handles these experiences. Think of witnessing a conversation: you turn your head from one person to the other, but seldom do you turn at the exact moment to catch the next speaker beginning—only an omniscient being could be so accurate. In reality you cannot know when another speaker will break in. Instead, a new voice intrudes and you turn your eyes to locate the speaker.

To make conversation seem spontaneous, the editor should mimic the way that eye attention and ear attention move, either by making picture cuts lag behind sound cuts, or sometimes by making them anticipate them. This replicates the disjunctive shifts we unconsciously make as eyes follow hearing, or hearing tunes in late to something just seen. This is quite simple in principle, but it will put your editing in a new league.

Effective cutting mimics the needs and reactions of a concerned Observer watching keenly for evidence of subtexts (hidden meanings and emotion developing in one or both characters). As a speaker begins a new point, we often switch ahead in search of its effect on her listener. Even as we ponder, the listener begins to reply. A hint of forcefulness causes us to switch attention over to the other person, now listening. The line of her mouth hardens, and we guess that she is disturbed.

Often the concerned Observer watching a conversation is processing complementary impressions— the speaker through hearing, but the listener through vision. We listen to the person who acts, but often scrutinize the person being acted-upon. When that situation reverses and the person acted-upon begins his reply, we glance back to see how the original speaker is reacting.

Human beings are forever searching out visual and aural clues—in facial expressions, body language, or vocal tone—that might unlock the protagonists’ hidden agenda. Good editing replicates this habitual searching process. By catching key moments of action, reaction, or subjective vision, it engages us in interpreting what is going on inside each protagonist. In dramatic terms, this is the search for subtext, for what is going on beneath the surface. Much of human life is spent doing this, and good cinema replicates this.

For the ambitious editor the message is clear: Be true to life by conveying the developing sensations of a concerned Observer. When you do this, sound and picture changeover points are seldom level cuts. Overlap cuts achieve this important disjunction by allowing the film to cut from shot to shot independently of the “his turn, her turn, his turn” speech alternations in the sound track.

Sometimes you want to bring a scene to a slow closure, perhaps with a fade-out, and then gently and slowly begin another, perhaps with a fade-in. But opticals (such as fades and dissolves) insert a rest period between scenes and usually you cannot afford to lose narrative momentum. Here is a transition between two scenes handled in three different ways:

A boy and girl are discussing going out together but the boy is worried that her mother will stop them. The girl says, “Oh don’t worry, I can convince her.” CUT TO the next scene, mother closes refrigerator with a bang and says firmly, “Absolutely not!” to the aggrieved daughter.

In this version, the girl says “Oh don’t worry,” and CUT TO the mother standing at the refrigerator as the girl’s voice-over ends, “I can convince her.” The mother slams the fridge door (which carries some metaphorical force) and says, “Absolutely not!”

Another way to merge one scene into the next would be to hold on the two after the girl speaks her line, and place the mother’s angry voice saying “Absolutely not!” over the tail end of their scene, then CUT TO the mother slamming the fridge door.

The first version makes the “joint” between sequences like a scene shift in the theatre. The second is something of a shock cut that emphasizes the mother’s determined opposition, while the third seems gentler and sympathetic to the difficulties of their romance.

You have also seen the lap cut carried out with sound effects: The factory worker rolls reluctantly out of bed, then as he shaves and dresses, we hear the increasingly loud sound of machinery until we CUT TO him working on the production line. Here anticipatory sound drags our attention forward to the next sequence. We do not find the location switch arbitrary since our curiosity demands an answer to the riddle of machine sounds in a bedroom. Alternatively we could see the man on the assembly line and CUT TO him putting food together in his kitchen at night. Holdover sound of factory uproar continues over the cut and slowly subsides as he wearily eats leftovers at his kitchen table.

In the first example, the aggressive factory sound draws him forward out of his bedroom; in the second, it lingers even after he has got home. Each lap cut implies a psychological narrative because each suggests that the sound exists in his head. From it we gather how unpleasant and omnipresent he finds his workplace. At home he thinks of it and is sucked up by it; after work the din follows him home to haunt him.

Overlap cuts soften transitions between locations, or suggest subtext and point of view through implying the inner consciousness of a central character. You could play it the other way, and let the silence of the home trail out into the workplace, so that he is seen at work, and the bedroom radio continues to play softly before being swamped by the rising uproar of the factory. At the end of the day, the sounds of laughter on the television set could displace the factory noise and make us CUT TO him sitting at home, relaxing with a sitcom.

Use sound and picture transitions creatively, and you transport the viewer forward with none of the ponderousness of optical effects like dissolves, fades, or (god help us) wipes. You can also scatter important clues to your characters’ inner lives and imaginations.

Here are some traps you’ll want to avoid that emerge during editing:

● Mis-identified sources: Allowing re-enacted or reconstructed material to stand unidentified in a film that is otherwise made of original and authentic materials can get you into trouble. Identify the material’s origin by narration or subtitle. Identify speakers too, if they need it, with subtitles.

● Mis-identified people: If you start an interior monologue voice-over (VO) on Person A and then reveal through a talking-head that it is actually Person B speaking, your audience will be irritated that you misled them. Make a practice of identifying VO by starting it over a shot of the speaker (doing his laundry, feeding the cat, etc.). Then you can continue the VO during other shots.

● Spatial errors: Check you are being true to essential geography, or your editing can suggest the kitchen is next to the bathroom, and London south of Madrid.

● Temporal mistakes: Show events in a chronology that is demonstrably wrong, and your detractors will seize it to discredit your whole film, as happened to Michael Moore with Roger and Me (USA, 1989).

● Elision distortions: Documentary editing involves compression: statements that serve the film but misrepresent the speaker’s original pronouncement may boomerang in court.

● Bogus truth: By juxtaposing unrelated events or statements, you manufacture meaning. Even though something may be invisible and insignificant to you and even to a general audience, participants can be scandalized. They cannot believe that you have compressed the nine months it took to buy their house into three shots. Be ready to defend and justify what you have done with other film examples.

● Participant fears: Sometimes you face a participant’s fear-fantasy when, after weeks of anguish, she wants to retract an innocuous statement that is vital to your film’s sense. She signed a release giving you the legal right to use it, and you know it can cause her no harm. Can you, should you, go ahead and override her wish? Your good name and career may suffer, and at the very least your conscience will prick you for violating her trust. Then again, you may have a lot of time or money invested. Perhaps a trusted third party can talk her out of her apprehension? A screening with a number of people she respects may also help.

● Informed consent: If you work for a media company, they will have an explicit consent policy designed to protect the integrity of the organization. When participants sign this informed consent form they are, in effect, declaring they understand you will use their material according to your own judgment, and that they understand the consequences. Though this permits you to imply a critical view of someone’s behavior or function, do you also have the moral right to deceive them and cause them harm? Public figures may be fair game, but private people usually deserve your diligent protection. Listening to your conscience is good, but getting the opinions of responsible friends and colleagues, and consulting a lawyer, are usually better. You may need to level with your participant, to see what he or she feels, but you must also make it clear that audiences watch documentaries because they are critical. They are not made to be flattering.

Ethical dilemmas seldom pose you a choice between right and wrong, but more often a choice between right versus right. So seek advice—and don’t feel that ethical dilemmas are ever something you must solve alone.

After considerable editing, a debilitating familiarity sets in and you lose confidence in your ability to make judgments. This is a particular hazard for director-editors who have long lived obsessively with the intentions for their footage. Soon every alternative version looks similar, and all seem too long. Be careful: this is a dangerous situation since you can begin inadvertently destroying your work. You need a technique to help objectify your judgments, and get some distance. Here are two steps I take. The first is to make a flow chart of your film so you can see its ideas and intentions in an alternative light. The other is to show the working cut to a trial audience of a chosen few.

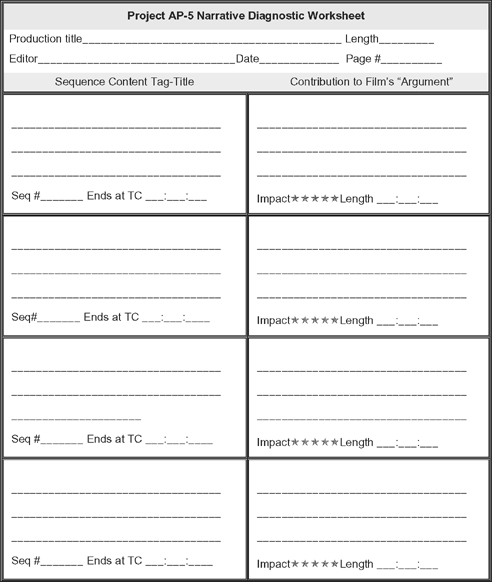

Film is an illusionary medium and deceives its makers even more than its audience. New understanding is hard to come by during editing, so it helps to translate something over-familiar into another form, as statisticians do by turning their figures into graphs and pie charts. The Narrative Diagnostic Worksheet (Table 15-1) will help you achieve an overview of your film’s contents, no matter how short or long it is. It works by producing a sort of annotated flow chart, from which you can make a functional analysis of your film and achieve a fresh perspective.

TABLE 15-1 Turning a film into an annotated flow chart—helpful when you face intractable problems

Project AP-5 Diagnosing a Narrative in the book’s website www.directingthedocumentary.com.

To use the worksheet,

1. Stop your film after each sequence and briefly describe its content in the box. It might simply convey a special mood or feeling, but more likely develops exposition, a new situation, or a new thematic strand. Perhaps it introduces a location or relationship that is developed later in the film.

2. Note what the sequence contributes to the film’s development as a whole.

3. Add timings (optional, but helpful for making decisions about the value of each sequence and the work’s overall length).

4. Award each sequence an impact rating of 1–5 stars (this helps you assess how well the strong and weak materials are distributed).

Your film has become a flow chart that shows you what is subconsciously present for any audience. How does its progression stack up? Here are some likely problems:

● Lack of early impact or a pedestrian opening that makes the film a late starter (fatal to TV or Internet viewings).

● Redundancy, especially of expository information.

● Necessary information inconsistently supplied.

● Holes or backtracking apparent in progression.

● Type and frequency of impact poorly distributed over the film’s length (resulting in uneven dramatic intensity and progression).

● Similar thematic contributions made several ways; choose the best and dump (or reposition) the rest.

● Material you like that fails to advance the film. Be brave and kill your darlings.

● The film’s conclusion emerges early, leaving the remainder an unnecessary recapitulation.

● Multiple endings—three is not uncommon. Decide what your film is really about, choose the most appropriate, and discard the rest.

As you can give each ailment a name, it suggests its own cure. Put these into effect, and you can feel rather than quantify the improvement.

After housecleaning, expect a new round of problems to surface, so make a new flow chart, however unconvinced you are of its necessity. Almost certainly you’ll find more anomalies.

This formal process will become second nature during your career, and will occur spontaneously. Even so, filmmakers of long standing invariably profit from subjecting their work to some such formal scrutiny. Work that hasn’t been rigorously critiqued looks sloppy and indulgent, and audiences have no patience for it.

Knowing what every brick in your movie’s edifice must accomplish, you are ready to test out your movie on a small audience. In a media organization this may be the people you work for—producers, senior editors, or a sponsor—so the experience will be grueling. Better is to first show the film to half a dozen whose tastes and interests you respect. The less they know about your film and your aims, the better. Warn them that it is a work in progress, and still technically raw, with materials missing—music, graphics, sound effects, end titles, whatever. Do place a working title at the front because it helps signal the film’s identity and purpose.

Before each public showing, run the film purely for sound levels. Even experienced filmmakers will misjudge a film whose sound varies between inaudible and overbearing. Present your film at its best, or be ready for misleadingly negative responses.

Working with the flow chart should have helped you decide what to explore with your first audience. You suspect which are the strong and weak points, and now you can find out.

After the viewing, ask first for impressions of the film as a whole. You are about to test the film’s working hypothesis and prove the “what it contributes” part of your analysis form. Don’t be afraid to focus and direct your viewers’ attention, or someone may lead off at a tangent.

Following is a typical order of inquiry. It starts with large impressions and issues, and moves down to the component parts:

● What do audience members think is the film’s theme, or themes?

● What are the major issues in the film?

● Did the film feel the right length or was it too long?

● Which parts were unclear or puzzling?

● Which parts felt slow?

● Which parts were moving or otherwise successful?

● What did they feel about … (name of character)?

● What did they end up knowing about … (situation or issue)?

Listen carefully, take notes, and retain your bearings toward the piece as a whole. Say no more than strictly necessary; never explain the film or explain what you intended, since that compromises your audience’s perceptions and suggests they are dumb. A film must stand alone without explication from its authors, so imbibe what your critics are saying. If these are your employers, all the more reason to be quietly receptive.

Depending on how interested your trial audience became in the discussion, you may get useful feedback on most of your film’s parts and intentions. Make allowance for the biases and subjectivity that emerge in your critics, and expect the occasional person who talks about the film he would have made, rather than the one you have just shown. When this happens (and it will), diplomatically redirect the discussion. If two or three people report the same difficulty, wait. Their feedback may elicit other comments canceling theirs out, in which case no action may be required.

This kind of listening takes great self-discipline since hearing negative reactions and criticism of your work is emotionally battering. Keep this in mind: when you ask for criticism, people look for possible changes—if only to make a contributory mark on your work. Expect to feel threatened, slighted, misunderstood, and unappreciated, and to come away with a raging headache. Handcuff yourself for three or four days so you do nothing to the film.

After one of these sessions it’s quite normal to feel that you have failed, that your film is junk, and that all is vanity. The fact is, works-in-progress always look fairly awful. Audiences are disproportionately affected by a wrong sound balance here, a shot or two that needs clipping, or a sequence that belongs earlier. What matters above all is that you hold on to your central intentions. Never revise these without strong and positive reasons to do so. For the time being, act only on those suggestions that support and further your central intentions. This is a dangerous time for the filmmaker, and indeed for any artist, since trying to please everyone makes it fatally easy to abandon your work’s underlying identity.

So, wait two or three days for your passions to cool. Run your film again, and you will see it with the eyes of the three people who failed to realize that the boy was the woman’s son. Yes, their relationship is twice implied, but you see a way to insert an extra line where the boy calls her “Mom.” Problem solved. You move on to the next one, and solve that too. This is the meat and potatoes of the artistic process.

When should a participant have the right to see and veto a cut? This seems like an easy and natural thing to agree, but in reality it is a minefield. Your work, like that of a journalist, counts as free speech, and you have a right to uncensored self-expression that you never relinquish without good cause. Keep in mind that participants seeing themselves on the screen, particularly for the first time, do so with great subjectivity. Most absolutely hate how they appear on the screen. To overcompensate in the hope of pleasing them is to abandon documentary for public relations.

So if you,

● Have made a film that might land you or your participants in legal trouble, get legal advice. Keep in mind that lawyers look on the dark side, look for snags, and err on the side of caution.

● Agreed at the outset that you would solicit participants’ feedback, then this is their right.

● Did not work out a consultative agreement with your subjects, then it’s a bad idea to embark on one now without very strong cause.

● Agree to show a work-in-progress cut to participants, then only do so after clearly explaining that their rights are limited to expressing preferences.

● Think a participant may feel upset or betrayed by something in your film, then prepare him or her in advance so he does not feel humiliated in the presence of family and friends. Fail, and that person may see you as a traitor and all film people as frauds.

Sticky situations at public showings usually go best if you have general audience members and the person’s friends and family present. The enjoyment and approval by the majority usually relieves the subject’s heightened sensitivities, and leaves him or her feeling good about the film as a whole.

Whether you are pleased or depressed about your film, it is always good to cease work for a while and do something else. You might take a week away from the film, or, if you are under deadline, go to a birthday party instead of working all night.

If this anxiety is new to you, take comfort: You are deep in the throes of the creative experience. This is the long, painful labor before giving birth. When you pick up the film again after a judicious lapse, your fatigue and defeatism will have gone away and the film’s problems and their solutions will seem manageable again.

A film of substance often requires an editing evolution of many months, and several new trial audiences. Show it again to the earliest audience at some point to see what progress they think you’ve made.

Try AP-5 Diagnosing a Narrative. It is a deceptively simple way of getting an overview on your film, but it usually springs some pleasant surprises and discoveries. It is particularly useful when you are getting to the end of your tether, and nearly always leads to making some important and very positive changes.