FIGURE 33-1

A what-if, suppositional voice narrates Night and Fog.

Many filmmakers shy away from narration because of its association with the voice-of-God discourses of yesteryear. This is a shame, since there is nothing more satisfying than knowing you have written some really effective narration. Usually it is indispensable in films about natural history, science, government, history, as well as in films that are avowedly journalistic or in diary form. You will assuredly have to write narration sometime in your career, so keep in mind that narration plays a vital role in three masterly documentaries praised in earlier chapters. I refer to Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog, Patricio Guzman’s Nostalgia for the Light, and Emad Burat and Guy Davidi’s Five Broken Cameras. In each, a master Storyteller creates a gripping counterpoint between imagery and an interior monologue. Each demonstrates how sensitively a narration can conduct us through humanity’s darker regions.

Narration is a lifesaver when used to rapidly and effectively introduce a new character, summarize intervening developments, or concisely supply a few vital facts. Especially when a film must fit much into a short duration, time saved in exposition is time gained elsewhere. Good narration,

● Supplies brief factual information.

● Uses the direct, active-voice language of speech.

● Uses the simplest words for the job.

● Is free of cliché.

● Gets the most meaning from the fewest syllables.

● Feels balanced and potent to the ear.

● Avoids emotional manipulation.

● Avoids value judgments, unless first established by pictorial evidence.

● Prepares us to notice evidence we might otherwise miss.

● Helps us when necessary to draw conclusions from the evidence.

● Describes what is already evident from the picture.

● Is condescending.

● Uses the pseudo-scientific passive voice.

● Uses convoluted sentences, and sonorous, ready-made phrases and clichés.

● Uses jargon or corporate-speak rather than workaday speech.

● Over-informs, leaving the audience no time to imagine or contemplate.

A narration can adopt any appropriate tradition of “voice” already established in other narrative forms such as theatre, literature, song, and poetry. Documentaries may therefore,

● Use a character’s voice-over as narration because he or she has insider knowledge and a right to an opinion.

● Take an omniscient or historical view, as do films that survey immigration, war, slavery, etc.

● Adopt the guise of a naively inquisitive visitor (as in films by Nicholas Broomfield, Michael Moore, and Morgan Spurlock).

● Take a what-if, suppositional voice, as in Cayrol’s commentary for Night and Fog (Alain Resnais, France, 1955, Figure 33-1), whose authority probably arises from Cayrol having been a Holocaust survivor himself.

● Express a poetic and musical identification with the subject, as in Basil Wright and Harry Watt’s Night Mail (GB, 1936, Figure 33-2 ).

● Radicalize the audience by using a bland or understated way of looking at an appalling situation, as in Luis Buñuel’s Land without Bread (Spain, 1932) or Burnat and Davidi’s Five Broken Cameras (Palestine/Israel/France/Netherlands, 2013).

FIGURE 33-1

A what-if, suppositional voice narrates Night and Fog.

FIGURE 33-2

Celebrating the dignity of the ordinary person’s labor in Night Mail.

● Use a letter- or diary-writing voice, as in the authentic war journals and correspondence from which Ken Burns builds much of the narration for The Civil War series (USA, 1990, Figure 33-3 ).

● Write a diary for the next generation, as Humphrey Jennings imagined a war pilot doing for his baby son in A Diary for Timothy (GB, 1946, Figure 33-4 ). The narration, by the novelist E.M. Forster, expresses a war-weary generation’s hope of resuming family life.

Viewers will assume that the narration is the voice of the film itself unless you establish that it is that of the filmmaker or one of the film’s characters. They will be influenced not only by what the narrator says, but disproportionately by the quality and associations of the narrator’s physical voice. The deep male “radio voice,” for instance, represents Authority with all its connotations of condescension and paternalism. The need to avoid stereotyping one’s own work makes finding an appropriate voice excruciatingly difficult. You will help yourself if you use narration sparingly and neutrally, leaving the audience as free as possible to develop its own judgment, values, and discrimination.

Perhaps you have a personal or anthropological film and need to provide factual links or set context. Maybe expositional material is lacking and the film’s story line needs simplifying. In each case, narration will probably emerge as the only practical answer. After you have assembled your movie, see how it stands on its own feet and whether it has any of these common problems:

● Difficulty getting the film started (convoluted and confusing setup).

● Origin and therefore authenticity of materials unclear (there might be some reconstruction, for instance).

FIGURE 33-3

A narration made from correspondence and war journals in The Civil War series.

FIGURE 33-4

In A Diary for Timothy the narration develops a war-weary generation’s hopes of eventually resuming normal life again.

● Audience needs more information on a participant’s thoughts, feelings, choices.

● Overcomplicated storyline needs simplifying.

● Getting from one good sequence to the next takes too much explaining by the participants.

● Film’s final issues lack focus so film fails to resolve satisfyingly.

When a lukewarm trial audience grows more enthusiastic after you added some off the cuff comments, you know that your film has problems, and narration may be the only way to supply the missing information succinctly.

Below are two common ways to create a narration, each with pros and cons.

The traditional method can work well if you base your film’s verbal narrative on a bona fide text such as letters or a diary, because the formality present in anyone’s reading will feel authentic. But if you want spontaneity or a one-to-one tone of intimacy, written narration nearly always fails, no matter how professional everyone is. Think how often the narration is what makes a film dull or dated. Common faults:

● Verbosity (a writing problem).

● Doubt over who or what the narrator represents (a question of the narrator’s authority).

● Something inauthentic or thespian in the narrator’s voice. It may be dull, condescending, egotistic, projecting, trying to entertain, trying to ingratiate, or have other distracting associations (a performance and/or casting problem).

Improvised narration can rather easily strike an informal, “one-on-one” relationship with the audience. It works because the speaker is having to create what he or she says on the spot, just as we do in daily life. Improvisation is good,

● When a participant serves as narrator.

● When you use your own voice in a “diary” film that must sound spontaneous and not scripted.

Below is what to do for each generative method.

It will help to write and record scratch (temporary) narration during editing. Then, by reading your words aloud against each film section, keep simplifying and refining your wording in search of the power of simplicity. It is normal to go through dozens of drafts before everything feels right and falls into place. When it comes time to record, the narrator will have a well-tried text.

Good writing must,

● Be consistent in tone, since it is now an additional “character” in the film.

● Pick up its sense and rhythm from the words of the last speaker and feed into those of the next.

● Be the right length so the narrator doesn’t have to speed up or slow down to fill the space.

● Allow your audience to notice things in picture before the narration comments on them. Narration that leads or accompanies what we notice turns your film into a slide-lecture.

Narration should follow the order in which the audience notices things. Sometimes you will have to adjust syntax by inverting the sentence structure. If, for instance, you have a shot of a big, rising sun with a small figure toiling across the landscape, you might first write, “She goes out before anyone else is about.” But the viewer notices the sun long before the human being, so your syntax is violating the order of perception. The viewer, unaware at first of any “she,” simply loses the rest of the sentence. However, reconfigure the syntax as “Before anyone else is up, she goes out” and the problem is solved. It works because you have complemented the order of perception (sun, landscape, woman) instead of blocking it.

Sometimes you must alter phrasing or break sentences apart to allow space for featured sound effects, such as a car door closing or a phone beginning to ring. Effects can create a powerful mood that helps drive the narrative forward, so don’t obscure them. They also help reduce the bane of documentary— verbal diarrhea (film industry shorthand for “too much loose talk.”)

When you write for film, never describe what we can already see. Narration must add information, never duplicate it. You would not say that the child is wearing a red raincoat (blatantly obvious from the shot) or that she is hesitant (subtly evident), but you can say she has just had her sixth birthday. This is legitimate additional information because it is not what we can see or infer.

Once you have written your narration, record a scratch (quick, trial) narration using any handy reader’s voice, including your own. Lay in the scratch narration (see “Secrets of Fitting Narration” below) and view your work several times dispassionately. Improved versions will jump out at you. You’ll see where you need pacing and emotional coloration changes, and that you must thin out the narration where the narrator is forced to hurry. Elsewhere the narration may seem perfunctory because it needs developing.

Now you can more easily imagine what kind of voice you’d prefer. Keep writing and rewriting until you’ve got every sentence and syllable just right. Now you are ready to think about auditioning and recording the final narrator.

The script you prepare should be a simple, double-spaced typescript, containing only what the narrator will read. Set blocks of narration apart on the page and number them for easy location. Try not to split a block across two pages, because the narrator may turn pages audibly during the recording. Where this is unavoidable, make pages rattle-proof by putting them inside plastic page protectors, or lay them flat so no handling is required while recording.

If you write a contract for the narrator, stipulate a proportion of call-back time in case you need additions at a later stage.

When you speak to a listener, your mind is occupied in finding the right words. Reading from a script however turns you into an audience for your own voice. A few highly experienced actors can overcome this, but they are rare. Documentary participants speaking from a script are going to have more difficulty still, even though the words and ideas were originally their own.

Directing a reader so that he or she sounds natural turns out to be the hardest thing in the world. Few readers can make a written narration sound remotely natural, not even highly trained actors. To guard against disappointment, start the process well in advance, record to picture (described later), and never assume all will be OK on the night, because it never is.

To test native ability, give each person something representative to read. Then ask for a different reading of the same material, to see how well each narrator responds to directions, which may involve meaning or tone. One reader focuses effectively on the new interpretation but relinquishes what was previously successful. Another reader may be anxious to please, can carry out instructions, but lacks a grasp of the larger picture. This is common with actors of limited experience.

Choosing an omniscient narrator is, as we have said, tantamount to choosing a personality for your film itself, and most voices will have disconcerting associations. For any number of reasons, most will simply sound horrendously wrong. As with any situation of choice, you should record several, even when you believe you have stumbled on perfection. After you make audition recordings, thank each person and give a date by which you will make a decision.

Make your final selection by trying speakers’ voices against the film until you are satisfied. Your final choice must be independent of personal liking or obligation. Make it solely on what you and your counselors agree is the best narration voice.

Show your chosen narrator the whole film and listen to his or her ideas about what it communicates and what the narration adds. Encouraging the narrator to find the right attitude and state of mind will do much to get written words sounding right. This is because we speak from thoughts, experiences, memories, and feelings. Invoking the whole person of the narrator gets better results than imagining that everything is already on the page and can be coached, sentence by sentence.

Record in a professional fashion, that is, with the picture running so that the narrator (listening on headphones) can key into the rhythms and intonation of adjacent voices in the film. As you go to record each section, the narrator should cease watching the picture (that is the job of the editor and director) and his or her headphones should be cut off from track in- and out-points, which would be distracting. No access to a studio? Set up your own rig with video playback and original sound made available to the artist via headphones. It will be more than worth the trouble.

Large organizations sometimes have access to landlines, conferencing facilities, and so forth which make it feasible to record a narrator from a distant location. This may work for history, science, or journalism, but a narrator in a remote location is difficult to engage emotionally for films that require a personal tone. No fiction director would choose to work miles apart from their actors, and nor should you.

Your best voice recording will probably come from having the speaker between 1 to 2 feet from the microphone. Surroundings should be acoustically dead (not enclosed or echoey), and there should be no background noise. Listen through good headphones or through a quality speaker in another room. It is critically important to get the best out of your narrator’s voice. Watch out for the voice trailing away at ends of sentences, for “popping” on plosive sounds, or distortion from overloading. Careful mike positioning and monitoring sound levels are vital.

The narrator should read each block of narration and wait for a cue (a gentle tap on the shoulder or a cue-light flash) before beginning the next. Rehearse first and give directions; phrase these positively and practically, giving instructions on what feeling to aim for rather than why. Stick to essentials, such as “Make the last part a little warmer” or “I’d like you to try that a bit more formally.” Name the quality or emotion you are after. After rehearsing each block, record it and move on to rehearsing the next.

Sometimes you will want to alter the word stressed in a sentence, or change the amount of projection the speaker is using (“Could you give me the same intensity but use less voice?” or “Use more voice and keep it up at the ends of sentences”). Occasionally a narrator will have some insurmountable problem with phrasing. Invite him or her to reword it while retaining the sense, but be on guard if this starts happening a lot. Sometimes narrators want to take over the writing. Let this happen only if you hear definite improvement.

Once you have recorded all the narration, play all the chosen parts back against the film so you can check that it all works. If you have any doubtful readings, make additional variants before letting the narrator go. These you audition later and use the best.

A spontaneous and informal narration is one that sounds like person-to-person conversation, and you can easily create this through interviewing. Under these circumstances the speaker’s mind is naturally engaged in finding words to act back on you, the interviewer—a familiar situation that unfailingly elicits normal speech. The drawback is that it may be hard to get the precision and compression possible through writing a narration. Ways to create an improvised narration follow.

This method lets you extract a highly spontaneous-sounding narration in the cutting room. Commonly, the director interviews the documentary’s “point of view” character carefully and extensively. Probably it is best done in spare moments during shooting while the chase is on, but do it in a really quiet place. When you interview, make sure the replies stand on their own as statements because you must eliminate your voice asking questions. Replies that overlap the question or lack self-contained starts won’t make sense unless you retain your question, which defeats the object of creating interior monologue material. For instance,

Q: “Tell us about how you make your catch in the bay”

A: “With pots, and a boat”

Remove the question, and “With pots, and a boat” is meaningless. So amend your question and ask again:

Q: “Tell us what your work is, what you catch, and how you go about it.”

Q: “ Well, I’m a lobster fisherman and we use lobster pots, and a boat to get from one ground to the next.”

Remove the “Well” and now you have a nice, affirmative statement that makes a serviceable first-person narration. As you interview, listen carefully to make sure you cover all your bases. Keep a list handy of what information you must elicit so nothing gets forgotten, and for anything at all important make sure you get more than one version from more than one person so you have options in the cutting room later.

Sync interviews can be used as sound-only voice over, cutting to the speaker’s image only at critical moments. Overused, however, this is the slippery slope to a talking head picture. You can also get people to talk to the camera while they go about their normal activities. The House, a 1996 British TV documentary series about London’s deteriorating Royal Opera, had wigmakers and set designers talking to the camera about the management’s failings while they powdered wigs or arranged props.

Today you aren’t bound to make transparent films —that is, ones that pretend we are seeing real life with no camera crew present. Nowadays we happily share the whole reality of filmmaking with the audience.

If you need to narrate your own film, get a trusted and demanding friend to interview you.

In this relatively structured method, you supply your narrator with a text that he or she reads, then gives back. When you ask interview questions, he or she replies in character, paraphrasing the information in the first or third person, as necessary. Finding the words to express the narration’s content reflects what happens in life; we know what we want to say, but must find the words to say it.

This method is good for creating, say, a historical character’s voice-over. It develops from a character or type of person the narrator has “become.” Together you go over who the narrator is and what this character wants the listener to know. Then you interview him, perhaps taking on a character role yourself so you can ask pertinent and leading questions. Replying from a defined role helps the narrator lock into a focused relationship.

Whenever you record a voice track, record some recording studio presence track or location atmosphere. As we have said earlier, this provides the editor with the right quality of “silence” to extend a pause or to add to the head of a narration block. Even in the same recording studio, and using the same mike, no two presence tracks (also called buzz track or room tone) are ever exactly alike.

However you generated narration, the same principles to fit it to picture apply. Following are little-known principles that greatly increase your narration’s effectiveness, and which will give your audience a strong sense of security and confidence in your film’s narrative voice.

Skillful writing and sensitive word placement gives you not just a tool of communication but an exquisitely accurate scalpel. For instance, if we cut shots together as in Figure 33-5; the outgoing shot is a still photo showing an artist at work at his easel, and the incoming shot shows a painting of a woman. The narration says, “Spencer used as a model first his wife and later the daughter of a friend.” By juxtaposing the words and images differently we can imply three quite different meanings. The crux lies in which word hits the incoming shot, as illustrated in the diagram. Using a single, unchanging section of narration, and the same three shots, we can in fact identify the person in the portrait as wife, daughter, or friend.

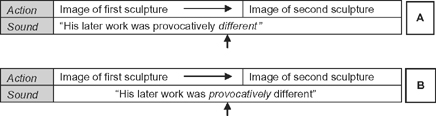

In another situation, illustrated in Figure 33-6, a simple shift in word positioning may alter, not an image’s meaning but its emotional shading. For instance, you see two shots, each of a piece of sculpture, and you hear the narrator say, “His later work was provocatively different.” Alter the relationship of narration to incoming image by a single word, and the second sculpture becomes either just “different” or “ provocatively different.” Something you should know: during a flow of words and accompanying images, the first word to coincide with each new image greatly influences how the audience interprets it.

Sometimes you put words to images, sometimes images against given dialogue or narration. A little-known secret to doing this well is to make use of the fact that speech has strong and weak points against which to position a picture cut. You can spot the strong points simply by treating it like music, so you hear patterns in the speaker’s language. In order to stress meaning, we inflect key syllables with a slightly louder volume or higher note. A mother might say to her recalcitrant teenager: “I want you to wait right here and don’t move. I’ll talk to you later.”

FIGURE 33-6

The first word on each new image affects how we interpret its meaning. Such “operative” words are italicized to demonstrate how emphasis can change. In (A) the later sculpture seems like a departure in the artist’s work, while in (B) the second sculpture evoked an excited reaction.

Different readings imply different subtexts, but a likely one is: “I want you to wait right here and don’t move. I’ll talk to you la ter. Stressed syllables encode the dominant intention, so I call them operative words. Using a split-page script form, we could design images to cut like this:

| Picture | Sound |

| Wide shot, woman and son. | “I want you to … |

| Close shot, boy’s mutinous face. | wait right here and … |

| Close shot, her hand on his shoulder. | don’t move. (pause) I’ll … |

| Close shot, mother’s determined face. | talk to you later.” |

By cutting to a new image on operative words, you punch home the mother’s determination and imply the boy’s stubborn resistance. In any well-edited fiction film, the rhythms intrinsic to this principle permeate the editing of dialogue scenes. You cannot preplan this, because the editing has to respond to the rhythms in the players and their physical movement. These subtly lead the audience’s expectations, and the editor, by orchestrating them, can exploit all the colorations of their subtexts (larger meanings hidden from sight).

When you edit, try to imagine you are a foreigner seeking meaning through people’s verbal music and body language. This is deeply ingrained in the psyche since that’s how we strained to understand the world as small children. Within a single sentence you hear rising and sinking tonal changes, rhythmic patterns like percussion in the stream of syllables, and dynamic variations of loud and soft. Working from this sensibility, your editing, shot selection, and placement now take place inside an essentially musical structure, and form a new, larger set of patterns. Here film, music, and dance joyfully link arms.

By paying attention to operative words and their potential, you will see patterns of pictures and words becoming receptive to each other, and falling into mutually responsive patterns. Magically effective, they drive the film along with an exhilarating sense of inevitability. Good editing is the compositional art that disguises art.

To bring this cinematic music to fruition when laying narration to picture, you will often have to make small picture-cutting changes, though sometimes altering the natural pauses in the narration will stretch or compress a section to produce the right lengths. Be very careful, however, not to disrupt the natural rhythms of the narrator or of a participant.