Farming has been a part of American heritage since the coming of the colonists. Although the number of farms in the United States has declined over the last 100 years, there are still more farms in the U.S. today than there were in the mid-1800s. The key difference is that today only a small percentage of the population’s livelihoods depend on farming; for comparison, during colonial times 90 percent of the population depended on agriculture for their survival and welfare.

The influence that farming has had in the development of America extends even to the country’s infrastructure. With farming being such a major part of society in colonial America, many towns were built along water features, such as bays and inlets, for the purposes of serving as a shipping point for export use.

This is not to say that all farms and farmers were prosperous. Typically, it was only the larger farms (and the merchants who owned them) that celebrated wealth; the smaller farms, homesteads and artisans had to struggle simply to get by, with most of what they raised either going towards their own family’s use, or used to trade for the things they needed, but could not produce themselves. This is to say nothing of the oftentimes steep taxes that farmers were forced to pay.

Nor were all locations created equal, either. In fact, the only element that all regions of colonial America and their associated farmers had in common was power. With all the equipment of the time powered by horses, oxen or humans, there was always a limit on what a farmer could reasonably accomplish in a growing season.

For the colonial American farmer operating in the New England/Plymouth colony areas, much of the soil was not good for growing, with fields close to the ocean being the worst locations. The farmers were forced to rely on hardier crops, such as barley, peas, and maize (Indian corn). Combined with long, harsh winters that seemed to come earlier every year, killing off crops that had yet to be harvested and livestock yet to be slaughtered, the cold months could prove fatal to many a farmer and their families.

Meanwhile, the colonies in the middle of America’s east coast were proving to be very prosperous, growing wheat, flax seed, oats, rye, corn and barley with relative ease for high profit. Their ability to sell their wheat and flour to the Europeans, in addition to a thriving export market for corn, helped farmers in colonies like Jamestown and other Virginian settlements thrive. The southern colonies were showing a similar degree of prosperity, focusing primarily on the recognized cash crops of tobacco, indigo and rice.

The typical early colonial farm house consisted of a dirt floor and walls built from logs, with no more than two rooms (and sometimes a loft), where the entire family lived. Everyone in the household worked, including the children, as soon as they were old enough to be assigned a task. Usually, boys would work with their fathers, and girls with their mothers, allowing them to learn the skills that would be necessary once they became adults themselves. The typical family size was large, ensuring that there would be always plenty of workers for the farm—families tended to have many children (made even more necessary due to the high rate of infant mortality during those early days). The whole family worked six days out of seven, with the seventh day set aside for church.

In the early nineteenth century, agriculture was still a predominate part of the economy of the United States, with sugar and cotton in the south and grains in the mid-west comprising a large percentage of the nation’s export business. By the mid-nineteenth century and very early twentieth century, new agricultural opportunities were opening up as a result of the canals and steamboats. New railroads, connecting increasingly large portions of the nation to itself, served to bring immigrant farmers to these newly opened areas. Agriculture continued to serve as the driving force of progress for the nascent nation.

It was during this time period that most of the Great Plains was opened as free range for cattle ranchers. Contrary to popular belief, the farmers of the plains didn’t lead as solitary a life as we might think; they actually led quite active social lives, turning barn building projects into barn raising events, inviting neighbors from miles around to come together and turn a construction project into a social event, complete with an assortment of foods (made for the occasion by the women). Agriculture, the great commonality between neighbors, even stronger than nationality, served to connect people to one another in mutually beneficial cooperation.

In 1862, the Homestead Act was signed into law by Abraham Lincoln, which gave 160 acre tracts of federal land to anyone 21 years of age or older (essentially, the head of the family). This land was provided free (or of little cost), as long as the recipient had never taken up arms against the federal government. The offer was even extended to women, immigrants and freed slaves, ensuring that the nation’s agricultural industry and economy did not falter in the wake of the American Civil War.

To further cement this, the requirements of the Homestead Act stated that you had to actually live on the land, build your home there and make other improvements to the land, including farming it for a minimum of five years. You also had to be a citizen, or file intent to become a citizen (freed slaves were already included under the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868.) The result was a new, actively involved work force cultivating land that would otherwise have remained fallow, during what should have been one of the most chaotic periods in the nation’s history.

By the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, most people were still living in rural areas. Although cash crops (produce intended for sale, rather than consumption) were now part of the picture, self-sufficiency was still the focus of daily life for many, and out-of-reach for some. It is at this point in history that the Industrial Revolution was beginning to hit its stride in America, with powered machinery beginning to be seen on the high-end, wealthy farms. While animal and human sources of power were still more important and more widely-used, systemic change in agriculture was on the horizon.

The introduction of farming machinery would change the face of American farming forever. Today, we still rely on high-powered machines to produce enough to feed the nation. Photo by Andrew Stawarz under the Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0.

But it would take something special to cause the down-to-earth American farmer to turn to machine power, revolutionizing the way agriculture was structured. That special something came in the first part of the twentieth century, a prosperous time for the American farmer, where U.S. farmers worked to fill the supply gap left by European farmers who had left their farms to fight in World War I. The American farmer now became a major supplier to Europe, a period that saw the American farm beginning to expand to meet the new demands, with many farmers going deep into debt. And, as the new technology came into its own, the family farm began to disappear in favor of larger, more efficient farms.

But the end of WWI would put an end to much of this prosperity. European farmers were returning to their farms and producing for the European market once again. Meanwhile, the American farmer now found themselves producing more than they could sell, despite being deep in debt already.

The 1920s and early 1930s brought no relief to these issues, as the high level of debt incurred by the expansion, not to mention collapsing land and food prices, led to farmers needing relief (or else a new line of work). It was at this time that President Hoover created the Federal Farm Board, a committee established by the Agriculture Marketing Act, one of his responses to the Great Depression. Adopted in 1929, it basically tailored the level of crop production to the county’s domestic needs, working to restrict over-production. Among their goals was the prevention of plunging crop prices, a real problem that farmers faced due to the buying, selling and storing of surplus crops. It also gave loans to farming-related organizations, which in turn offered loans directly to farmers for their seed and livestock. Things were improving, but too slowly to really get ahead of the issue.

Between 1933 and 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal appeared on the scene. A series of domestic programs designed to address the issues of the Great Depression and return the nation to its former prosperity, the New Deal also contained a number of farming programs, including the Farm Securities Act, which raised farm incomes by reducing output; and the Agriculture Adjustment Administration and the Agriculture Adjustment Act, which set higher wholesale prices (and higher income for the farmer) by keeping production low. This was later ruled unconstitutional, and was replaced in 1936 with a similar program that paid farmers to raise soil-enriching crops (which would never reach the marketplace), instead of just leaving the cropland bare and unproductive. Again, as with the Homestead Act before it, the intention was to keep the infrastructure of the agricultural industry strong and progressive. Many of these farm subsidies still exist in some form today.

These efforts eventually paid off. By World War II, agriculture was beginning to revive itself. As farming was still considered an important and necessary occupation, farmers were exempt from the draft. By the mid-1940s, farms were once again becoming larger, but the number of farms in existence was lower, in an effort to prevent a similar post-war collapse. Some farmers went part-time, while others sold out and moved to town or to the city.

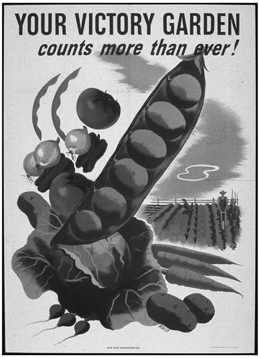

Agriculture was so important to America’s continued prosperity that growing crops was presented as a form of patriotism.

The second part of the twentieth century also saw a geographical shift in agricultural production, as farming became more common in the south and west. Electric motors and irrigation became more commonplace, offering higher levels of efficiency to even small-scale farmers. Electricity started to be more widely available in rural areas, creating major innovations such as grain elevators and modern milk parlors. It also (for better or worse, depending on your view) assisted in the creation of confined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, to better match the nation’s demand for livestock and livestock by-products.

Today, there are fewer farms in America than there have been in the past, but their output and overall efficiency are much higher. And, as more people find their way back to the land, whether on a large farm, small homestead or backyard garden, this number will continue to grow. Too many people have lost their connection to where their food comes from; but many are trying to get it back, teaching their friends, children, and even grandchildren about the importance of fresh, local and home-grown food. As a result, we are seeing an upsurge in backyard farms, community food gardens and small homesteads.

And with consumer spending on “food” plants now higher than decorative plants, the trend doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon!