CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

HUMAN SKELETAL AND MUSCLE SYSTEMS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

The skeleton is the most fundamental component of human anatomy. It serves not only as a framework for the body, providing places for the attachment of muscles and other tissues, but also serves as a protective barrier for vital organs, such as the brain and heart. The skeleton consists of many individual bones and cartilages. There also are bands of fibrous connective tissue—the ligaments and the tendons—in intimate relationship with the parts of the skeleton.

The human skeleton, like that of other vertebrates, consists of two principal subdivisions, each with origins distinct from the others and each presenting certain individual features. These are (1) the axial, comprising the vertebral column—the spine—and much of the skull, and (2) the appendicular, to which the pelvic (hip) and pectoral (shoulder) girdles and the bones and cartilages of the limbs belong.

When one considers the relation of these subdivisions of the skeleton to the soft parts of the human body—such as the nervous system, the digestive system, the respiratory system, the cardiovascular system, and the voluntary muscles of the muscle system—it is clear that the functions of the skeleton are of three different types: support, protection, and motion. Of these functions, support is the most primitive and the oldest; likewise, the axial part of the skeleton was the first to evolve. The vertebral column, corresponding to the notochord in lower organisms, is the main support of the trunk.

A distinctive characteristic of humans as compared with other mammals is erect posture. The human body is to some extent like a walking tower that moves on pillars, represented by the legs. Tremendous advantages have been gained from this erect posture, the chief among which has been the freeing of the arms for a great variety of uses. Nevertheless, erect posture has created a number of mechanical problems—in particular, weight bearing. These problems have had to be met by adaptations of the skeletal system.

Protection of the heart, lungs, and other organs and structures in the chest requires a flexible and elastic covering that can move with the organs as they expand and contract. Such a covering is provided by the bony thoracic basket, or rib cage, which forms the skeleton of the wall of the chest, or thorax. The connection of the ribs to the breastbone—the sternum—is in all cases a secondary one, brought about by the relatively pliable rib (costal) cartilages. The small joints between the ribs and the vertebrae permit a gliding motion of the ribs on the vertebrae during breathing and other activities. The motion is limited by the ligamentous attachments between ribs and vertebrae.

The third general function of the skeleton is that of motion. The great majority of the skeletal muscles are firmly anchored to the skeleton, usually to at least two bones and in some cases to many bones. Thus, the motions of the body and its parts, all the way from the lunge of the football player to the delicate manipulations of a handicraft artist or of the use of complicated instruments by a scientist, are made possible by separate and individual engineering arrangements between muscle and bone.

The cranium—the part of the skull that encloses the brain—is sometimes called the braincase. The primary function of the cranium is to protect the brain; however, it also serves as an important role in providing a connective medium for the muscles of the face and for the tissues of the brain.

The cranium is formed of bones of two different types of developmental origin—the cartilaginous, or substitution, bones, which replace cartilages preformed in the general shape of the bone; and membrane bones, which are laid down within layers of connective tissue. For the most part, the substitution bones form the floor of the cranium, while membrane bones form the sides and roof.

The range in the capacity of the cranial cavity is wide but is not directly proportional to the size of the skull, because there are variations also in the thickness of the bones and in the size of the air pockets, or sinuses. The cranial cavity has a rough, uneven floor, but its landmarks and details of structure generally are consistent from one skull to another.

The cranium forms all the upper portion of the skull, with the bones of the face situated beneath its forward part. It consists of a relatively few large bones, the frontal bone, the sphenoid bone, two temporal bones, two parietal bones, and the occipital bone. The frontal bone underlies the forehead region and extends back to the coronal suture, an arching line that separates the frontal bone from the two parietal bones, on the sides of the cranium. In front, the frontal bone forms a joint with the two small bones of the bridge of the nose and with the zygomatic bone (which forms part of the cheekbone), the sphenoid, and the maxillary bones. Between the nasal and zygomatic bones, the horizontal portion of the frontal bone extends back to form a part of the roof of the eye socket, or orbit; it thus serves an important protective function for the eye and its accessory structures.

Each parietal bone has a generally four-sided outline. Together they form a large portion of the side walls of the cranium. Each adjoins the frontal, the sphenoid, the temporal, and the occipital bones and its fellow of the opposite side. They are almost exclusively cranial bones, having less relation to other structures than the other bones that help to form the cranium.

The interior of the cranium shows a multitude of details, reflecting the shapes of the softer structures that are in contact with the bones. In addition the base of the cranium is divided into three major depressions, or fossae, which are divided strictly according to the borders of the bones of the cranium but are related to major portions of the brain. The anterior cranial fossa serves as the bed in which rest the frontal lobes of the cerebrum, the large forward part of the brain. The middle cranial fossa, sharply divided into two lateral halves by a central eminence of bone, contains the temporal lobes of the cerebrum. The posterior cranial fossa serves as a bed for the hemispheres of the cerebellum (a mass of brain tissue behind the brain stem and beneath the rear portion of the cerebrum) and for the front and middle portion of the brain stem. Major portions of the brain are thus partially enfolded by the bones of the cranial wall.

There are openings in the three fossae for the passage of nerves and blood vessels, and the markings on the internal surface of the bones are from the attachments of the brain coverings—the meninges—and venous sinuses and other blood vessels.

The anterior cranial fossa shows a crestlike projection in the midline, the crista galli (“crest of the cock”). This is a place of firm attachment for the falx cerebri, a subdivision of dura mater that separates the right and left cerebral hemispheres. On either side of the crest is the cribriform (pierced with small holes) plate of the ethmoid bone, a midline bone important as a part both of the cranium and of the nose. At the sides of the cribriform plate are the orbital plates of the frontal bone, which form the roofs of the eye sockets.

The rear part of the anterior cranial fossa is formed by those portions of the sphenoid bone called its body and lesser wings. Projections from the lesser wings, the anterior clinoid (bedlike) processes, extend back to a point beside each optic foramen, an opening through which important optic nerves, or tracts, enter into the protection of the cranial cavity after a relatively short course within the eye socket.

The central eminence of the middle cranial fossa is specialized as a saddlelike seat for the pituitary gland. The posterior portion of this seat, or sella turcica (“Turk’s saddle”), is actually wall-like and is called the dorsum sellae. The pituitary gland is thus situated in almost the centre of the cranial cavity.

The deep lateral portions of the middle cranial fossa contain the temporal lobes of the cerebrum. Also in the middle fossa is the jagged opening called the foramen lacerum. The lower part of the foramen lacerum is blocked by fibrocartilage, but through its upper part passes the internal carotid artery, surrounded by a network of nerves, as it makes its way to the interior of the cranial cavity.

The posterior cranial fossa is above the vertebral column and the muscles of the back of the neck. The foramen magnum, the opening through which the brain and the spinal cord make connection, is in the lowest part of the fossa. Through other openings in the posterior cranial fossa, including the jugular foramina, pass the large blood channels called the sigmoid sinuses and also the 9th (glossopharyngeal), 10th (vagus), and 11th (spinal accessory) cranial nerves as they leave the cranial cavity.

The primary function of the hyoid bone is to serve as an anchoring structure for the tongue. The bone is situated at the root of the tongue in the front of the neck and between the lower jaw and the largest cartilage of the larynx, or voice box. It has no articulation with other bones and thus has a purely anchoring function, and it is more or less in the shape of a U, with the body forming the central part, or base, of the letter.

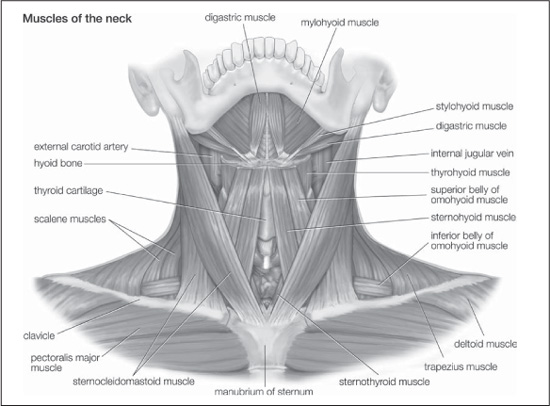

The hyoid bone has certain muscles of the tongue attached to it. Through these muscle attachments, the hyoid plays an important role in chewing (mastication), in swallowing, and in voice production. At the beginning of a swallowing motion, the geniohyoid and mylohyoid muscles elevate the bone and the floor of the mouth simultaneously. These muscles are assisted by the stylohyoid and digastric muscles. The tongue is pressed upward against the palate, and the food is forced backward.

The larger part of the skeleton of the face is formed by the maxillae. Though they are called the upper jaws, the extent and functions of the maxillae include much more than serving as complements to the lower jaw, or mandible. They form the middle and lower portion of the eye socket. They have the opening for the nose between them, and they form the sharp projection known as the anterior nasal spine.

The infraorbital foramen, an opening into the floor of the eye socket, is the forward end of a canal through which passes the infraorbital branch of the maxillary nerve, the second division of the fifth cranial nerve. In addition the alveolar margin, containing the alveoli, or sockets, in which all the upper teeth are set, forms the lower part of each maxilla, and lateral projections form the zygomatic process, creating a joint with the zygomatic, or malar, bone (cheekbone).

The left and right halves of the lower jaw, or mandible, begin originally as two distinct bones, but in the second year of life the two bones fuse at the midline. The horizontal central part on each side is the body of the mandible. The projecting chin, at the lower part of the body in the midline, is said to be a distinctive characteristic of the human skull.

The ascending parts of the mandible at the side are called rami (branches). The joints by means of which the lower jaw is able to make all its varied movements are between a rounded knob, or condyle, at the upper back corner of each ramus and a depression, called a glenoid fossa, in each temporal bone. Another, rather sharp projection at the top of each ramus and in front, called a coronoid process, attaches to the temporalis muscle, which serves with other muscles in shutting the jaws. On the inner side of the ramus of either side is a large, obliquely placed opening into a channel, the mandibular canal, for nerves, arteries, and veins.

The zygomatic arch, forming the cheekbone, consists of portions of three bones: the maxilla, in front; the zygomatic bone, centrally in the arch; and a projection from the temporal bone to form the rear part. The zygomatic arch actually serves as a firm bony origin for the powerful masseter muscle, which descends from it to insert on the outer side of the mandible. The masseter muscle shares with the temporalis muscle and lateral and medial pterygoid muscles the function of elevating the mandible in order to bring the lower against the upper teeth, thus achieving a bite.

The assumption of erect posture during the development of the human species has led to a need for adaptation and changes in the human skeletal system. The very form of the human vertebral column is due to such adaptations and changes.

Viewed from the side, the vertebral column is not actually a column but rather a sort of spiral spring in the form of the letter S. The newborn child has a relatively straight backbone. The development of the curvatures occurs as the supporting functions of the vertebral column in humans—i.e., holding up the trunk, keeping the head erect, serving as an anchor for the extremities—are developed.

Side view of human vertebral column. © SuperStock, Inc.

The S-curvature enables the vertebral column to absorb the shocks of walking on hard surfaces; a straight column would conduct the jarring shocks directly from the pelvic girdle to the head. The curvature meets the problem of the weight of the viscera. In an erect animal with a straight column, the column would be pulled forward by the viscera. Additional space for the viscera is provided by the concavities of the thoracic and pelvic regions.

The space between the spinal cord and the vertebrae is occupied by the meninges, by the cerebrospinal fluid, and by a certain amount of fat and connective tissue. In front are the heavy centrums, or bodies, of the vertebrae and the intervertebral disks—the tough, resilient pads between the vertebral bodies. The portion of each vertebra called the neural arch encloses and protects the back and sides of the spinal cord. Between the neural arches are sheets of elastic connective tissue, the interlaminar ligaments, or ligamenta flava. Here some protective function has to be sacrificed for the sake of motion, because a forward bending of part of the column leads to separation between the laminae and between the spines of the neural arches of adjoining vertebrae.

Besides its role in support and protection, the vertebral column is important in the anchoring of muscles. Many of the muscles attached to it act to move either the column itself or various segments of it. Some are relatively superficial, and others are deep-lying. The large and important erector spinae, as the name implies, holds the spine erect. It begins on the sacrum (the large triangular bone at the base of the spinal column) and passes upward, forming a mass of muscle on either side of the spines of the lumbar vertebrae. It then divides into three columns, ascending over the back of the chest.

Small muscles run between the transverse processes (projections from the sides of the neural rings) of adjacent vertebrae, between the vertebral spines (projections from the centres of the rings), and from transverse process to spine, giving great mobility to the segmented bony column.

The anchoring function of the spinal column is of great importance for the muscles that arise on the trunk, in whole or in part from the column or from ligaments attached to it, and that are inserted on the bones of the arms and legs. Of these muscles, the most important for the arms are the latissimus dorsi (drawing the arm backward and downward and rotating it inward), the trapezius (rotating the shoulder blade), the rhomboideus, and the levator scapulae (raising and lowering the shoulder blade); for the legs, the psoas (loin) muscles.

The rib cage, or thoracic basket, consists of the 12 thoracic (chest) vertebrae, the 24 ribs, and the breastbone, or sternum. The ribs are curved, compressed bars of bone, with each succeeding rib, from the first, or uppermost, becoming more open in curvature. The place of greatest change in curvature of a rib, called its angle, is found several inches (cm) from the head of the rib, the end that forms a joint with the vertebrae.

The first seven ribs are attached to the breastbone by cartilages called costal cartilages; these ribs are called true ribs. Of the remaining five ribs, which are called false, the first three have their costal cartilages connected to the cartilage above them. The last two, the floating ribs, have their cartilages ending in the muscle in the abdominal wall.

Through the action of a number of muscles, the rib cage, which is semirigid but expansile, increases its size. The pressure of the air in the lungs thus is reduced below that of the outside air, which moves into the lungs quickly to restore equilibrium. These events constitute inspiration (breathing in). Expiration (breathing out) is a result of relaxation of the respiratory muscles and of the elastic recoil of the lungs and of the fibrous ligaments and tendons attached to the skeleton of the thorax. A major respiratory muscle is the diaphragm, which separates the chest and abdomen and has an extensive origin from the rib cage and the vertebral column. The configuration of the lower five ribs gives freedom for the expansion of the lower part of the rib cage and for the movements of the diaphragm.

The upper and lower extremities of humans offer many interesting points of comparison and of contrast. They and their individual components are homologous—i.e., of a common origin and patterned on the same basic plan. A long evolutionary history and profound changes in the function of these two pairs of extremities have led, however, to considerable differences between them.

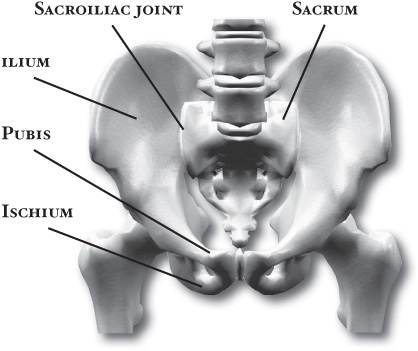

The girdles are those portions of the extremities that are in closest relation to the axis of the body and that serve to connect the free extremity (the arm or the leg) with that axis, either directly, by way of the skeleton, or indirectly, by muscular attachments. The connection of the pelvic girdle to the body axis, or vertebral column, is by means of the sacroiliac joint. On the contiguous surfaces of the ilium (the rear and upper part of the hip bone) and of the sacrum (the part of the vertebral column directly connected with the hip bone) are thin plates of cartilage. The bones are closely fitted together in this way, and there are irregular masses of softer fibrocartilage in places joining the articular cartilages; at the upper and posterior parts of the joint there are fibrous attachments between the bones. In the joint cavity there is a small amount of synovial fluid. Strong ligaments, known as anterior and posterior sacroiliac and interosseous ligaments, bind the pelvic girdle to the vertebral column. These fibrous attachments are the chief factors limiting motion of the joint, but the condition, or tone, of the muscles in this region is important in preventing or correcting the sacroiliac problems that are of common occurrence.

Pelvic girdle with views of the sacroiliac joint, ilium, sacrum, pubis, and ischium. © SuperStock, Inc.

The pelvic girdle consists originally of three bones, which become fused in early adulthood and each of which contributes a part of the acetabulum, the deep cavity into which the head of the femur is fitted. The flaring upper part of the girdle is the ilium; the lower anterior part, meeting with its fellow at the midline, is the pubis; and the lower posterior part is the ischium. Each ischial bone has a prominence, or tuberosity, and it is upon these tuberosities that the body rests when seated.

The components of the girdle of the upper extremity, the pectoral girdle, are the shoulder blade, or scapula, and the collarbone, or clavicle. The head of the humerus, the long bone of the upper arm, fits into the glenoid cavity, a depression in the scapula. The pectoral girdle is not connected with the vertebral column by ligamentous attachments, nor is there any joint between it and any part of the axis of the body. The connection is by means of muscles only, including the trapezius, rhomboids, and levator scapulae, while the serratus anterior connects the scapula to the rib cage. The range of motion of the pectoral girdle, and in particular of the scapula, is enormously greater than that of the pelvic girdle.

Another contrast, in terms of function, is seen in the shallowness of the glenoid fossa, as contrasted with the depth of the acetabulum. It is true that the receptacle for the head of the humerus is deepened to some degree by a lip of fibrocartilage known as the glenoid labrum, which, like the corresponding structure for the acetabulum, aids in grasping the head of the long bone. The range of motion of the free upper extremity is, however, far greater than that of the lower extremity. With this greater facility of motion goes a greater risk of dislocation. For this reason, of all joints of the body, the shoulder is most often the site of dislocation.

The humerus and the femur are corresponding bones of the arms and legs, respectively. While their parts are similar in general, their structure has been adapted to differing functions. The head of the humerus is almost hemispherical, while that of the femur forms about two-thirds of a sphere. There is a strong ligament passing from the head of the femur to further strengthen and ensure its position in the acetabulum.

The anatomical neck of the humerus is only a slight constriction, while the neck of the femur is a very distinct portion, running from the head to meet the shaft at an angle of about 125 degrees. Actually, the femoral neck is developmentally and functionally a part of the shaft. The entire weight of the body is directed through the femoral heads along their necks and to the shaft.

The forearm and the lower leg have two long bones each. In the forearm are the radius—on the thumb side of the forearm—and the ulna; in the lower leg are the tibia (the shin) and the fibula. The radius corresponds to the tibia and the ulna to the fibula. The knee joint is not only the largest joint in the body but also perhaps the most complicated one. The bones involved in it, however, are only the femur and the tibia, although the smaller bone of the leg, the fibula, is carried along in the movements of flexion, extension, and slight rotation that this joint permits. The very thin fibula is at one time in fetal development far thicker relative to the tibia than it is in the adult skeleton.

At the elbow, the ulna forms with the humerus a true hinge joint, in which the actions are flexion and extension. In this joint a large projection of the ulna, the olecranon, fits into the well-defined olecranon fossa, a depression of the humerus.

The radius is shorter than the ulna. Its most distinctive feature is the thick disk-shaped head, which has a smoothly concave superior surface to articulate with the head, or capitulum, of the humerus. The head of the radius is held against the notch in the side of the ulna by means of a strong annular, or ring-shaped, ligament. Although attached to the ulna, the head of the radius is free to rotate. As the head rotates, the shaft and outer end of the radius are swung in an arc. In the position of the arm called supination, the radius and ulna are parallel, the palm of the hand faces forward, and the thumb is away from the body. In the position called pronation, the radius and ulna are crossed, the palm faces to the rear, and the thumb is next to the body. There are no actions of the leg comparable to the supination and pronation of the arm.

The skeleton of the wrist, or carpus, consists of eight small carpal bones, which are arranged in two rows of four each. The skeleton of the ankle, or tarsus, has seven bones, but, because of the angle of the foot to the leg and the weight-bearing function, they are arranged in a more complicated way. The bone of the heel, directed downward and backward, is the calcaneus, while the “keystone” of the tarsus is the talus, the superior surface of which articulates with the tibia.

In the skeleton of the arms and legs, the outer portion is specialized and consists of elongated portions made up of chains, or linear series, of small bones. In an evolutionary sense, these outer portions appear to have had a complex history and, within the human mammalian ancestry, to have passed first through a stage when all four would have been “feet,” serving as the weight-bearing ends of extremities, as in quadrupeds in general. Second, all four appear to have become adapted for arboreal life, as in the lower primates. Third, and finally, the assumption of an upright posture has brought the distal portions of the hind, now lower, extremities back into the role of feet, while those of the front, now upper, extremities have developed remarkable manipulative powers and are called hands.

In humans the metatarsal bones, those of the foot proper, are larger than the corresponding bones of the hands, the metacarpal bones. The tarsals and metatarsals form the arches of the foot, which give it strength and enable it to act as a lever. The shape of each bone and its relations to its fellows are such as to adapt it for this function.

The phalanges—the toe bones—of the foot have bases relatively large compared with the corresponding bones in the hand, while the shafts are much thinner. The middle and outer phalanges in the foot are short in comparison with those of the fingers. The phalanges of the big toe have special features.

The hand is an instrument for fine and varied movements, with the thumb and its parts (the first metacarpal bone and the two phalanges) being extremely important. The free movements of the thumb include—besides flexion, extension, abduction (ability to draw away from the first finger), and adduction (ability to move forward of the fingers), which are exercised in varying degrees by the big toe also—a unique action, that of opposition, by which the thumb can be brought across, or opposed to, the palm and to the tips of the slightly flexed fingers. This motion forms the basis for the handling of objects.

The muscles of the human body combine form and function to produce movements ranging from the delicate precision and grace of a ballet dancer to the explosive power of a sprinter. But muscles do far more than simply move the body—they provide heat, protection, and support, and they convey information about human experiences through the control of facial expression. Muscles that direct the skeletal system are said to be under voluntary control and are concerned with movement, posture, and balance. However, there also are a number of muscles that work automatically, performing vital functions such as digestion while allowing conscious thought to be focused on other activities.

Broadly considered, human muscle—like the muscles of all vertebrates—is often divided into striated muscle (or skeletal muscle), smooth muscle, and cardiac muscle. Smooth muscle is under involuntary control and is found in the walls of blood vessels and of structures such as the urinary bladder, the intestines, and the stomach. Cardiac muscle makes up the mass of the heart and is responsible for the rhythmic contractions of that vital pumping organ; it too is under involuntary control. With very few exceptions, the arrangement of smooth muscle and cardiac muscle in humans is identical to the arrangement found in other vertebrate animals.

The arrangement of striated muscle in modern humans conforms to the basic plan seen in all pronograde quadrupedal vertebrates and mammals (that is, all vertebrates and mammals that assume a horizontal and four-legged posture). The primates (the order of mammals to which human beings belong) inherited the primitive quadrupedal stance and locomotion, but since their appearance in the Late Cretaceous Period some 65 million years ago, several groups have modified their locomotor system to concentrate on the use of the arms for propulsion through the trees. The most extreme expression of this skeletal adaptation in living primates is seen in the modern gibbon family. Their forelimbs are relatively elongated, they hold their trunk erect, and, for the short periods that they spend on the ground, they walk only on their hind limbs (in a bipedal fashion).

Modern humans are most closely related to the living great apes: the chimpanzee, the gorilla, and the orangutan. The human’s most distant relative in the group, the orangutan, has a locomotor system that is adapted for moving among the vertical tree trunks of the Asian rain forests. It grips these trunks equally well with both fore and hind limbs and was at one time aptly called quadrumanal, or “four-handed.”

There is little direct fossil evidence about the common ancestor of modern humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas, so inferences about its habitat and locomotion must be made. The ancestor was most likely a relatively generalized tree-dwelling animal that could walk quadrupedally along branches as well as climb between them. From such an ancestor, two locomotor trends were apparently derived. In one, which led to the gorillas and the chimpanzees, the forelimbs became elongated, so when these modern animals come to the ground, they support their trunks by placing the knuckles of their outstretched forelimbs on the ground. The second trend involved shortening the trunk, relocating the shoulder blades, and, most important, steadily increasing the emphasis on hind limb support and truncal erectness. In other words, this trend saw the achievement of an upright bipedal, or orthograde, posture instead of a quadrupedal, or pronograde, one. The upright posture probably was quite well established by 3 million to 3.5 million years ago, as evidenced both by the form of the limb bones and by the preserved footprints of early hominids found from this time.

The major muscular changes directly associated with the shift to bipedal locomotion are seen in the lower limb. The obvious skeletal changes are in the length of the hind limb, the development of the heel, and the change in the shape of the knee joint so that its surface is flat and not evenly rounded. The hind limbs of apes are relatively short for their body size, compared with modern human proportions.

The changes that occurred in the bones of the pelvis are not all directly related to the shift in locomotion, but they are a consequence of it. Bipedality, by freeing the hands from primary involvement with support and locomotion, enabled the development of manual dexterity and thus the manufacture and use of tools, which has been linked to the development in human ancestors of language and other intellectual capacities. The result is a substantially enlarged brain. Large brains clearly affect the form of the skull and thus the musculature of the head and neck. A larger brain also has a direct effect on the pelvis because of the need for a wide pelvic inlet and outlet for the birth of relatively large-brained young. A larger pelvic cavity means that the hip joints have to be farther apart. Consequently, the hip joints are subjected to considerable forces when weight is taken on one leg, as it has to be in walking and running.

To counteract this, the muscles (gluteus minimus and gluteus medius) that are used by the chimpanzee to push the leg back (hip extensors) have shifted in modern humans in relation to the hip joint, so that they now act as abductors to balance the trunk on the weight-bearing leg during walking. Part of a third climbing muscle (gluteus maximus) also assists in abduction as well as in maintaining the knee in extension during weight bearing. The gluteal muscles are also responsible for much of the rotation of the hip that has to accompany walking. When the right leg is swung forward and the right foot touches the ground, the hip joint of the same side externally rotates, whereas that of the opposite side undergoes a similar amount of internal rotation. Both these movements are made possible by rearrangements of the muscles crossing the hip.

The bones of the trunk and the lower limb are so arranged in modern humans that to stand upright requires a minimum of muscle activity. Some muscles, however, are essential to maintaining balance, and the extensors of the knee have been rearranged and realigned, as have the muscles of the calf.

The foot is often but erroneously considered to be a poor relation of the hand. Although the toes in modern humans are normally incapable of useful independent movement, the flexor muscles of the big toe (hallux) are developed to provide the final push off in the walking cycle. Muscles of all three compartments of the modern human lower leg contribute to making the foot a stable platform, which nonetheless can adapt to walking over rough and sloping ground.

The human upper limb has retained an overall generalized structure, with its details adapted to upright existence. Among the primitive features that persist are the clavicle, or collarbone, which still functions as part of the shoulder; pronation and supination; and a full complement of five digits in the hand.

Pronation and supination of the forearm, which allowthe palm of the hand to rotate 180 degrees, is not peculiar to humans. This movement depends upon the possession of both a small disk in the wrist joint and an arrangement of the muscles such that they can rotate the radius to and fro. Both the disk and the muscle arrangement are present in the great apes.

In quadrupedal animals the thorax (chest) is suspended between the shoulder blades by a muscular hammock formed by the serratus anterior muscle. In upright sitting and standing, however, the shoulder girdle is suspended from the trunk. The scapula, or shoulder blade, floats over the thoracic surface by reason of the arrangement of the fibres of the serratus anterior muscle and the support against gravity that is provided by the trapezius, rhomboid, and levator scapulae muscles. When the arms are required to push forward against an object at shoulder level, their action is reminiscent of quadrupedal support.

The change in shape of the chest to emphasize breadth rather than depth altered the relation of muscles in the shoulder region, with an increase in size of the latissimus dorsi muscle and the pectoralis major muscle. The human pectoralis minor muscle has forsaken its attachment to the humerus, the long bone of the upper arm, and presumably derives some stability from attaching to the coracoid process, a projection from the scapula, instead of gliding over it.

The hand of a chimpanzee is dexterous, but the proportions of the digits and the rearrangement and supplementation of muscles are the major reasons for the greater manipulative ability of the hand of a modern human. Most of these changes are concentrated on the thumb. For example, modern humans are the only living hominids to have a separate long thumb flexor, and the short muscle that swings the thumb over toward the palm is particularly well developed in humans. This contributes to the movement of opposition that is crucial for the so-called precision grip—i.e., the bringing together of the tips of the thumb and forefinger.

The muscle group of the head and neck is most directly influenced by the change to an upright posture. This group comprises the muscles of the back (nape) and side of the neck. Posture is not the only influence on these muscles, for the reduction in the size of the jaws in modern humans also contributes to the observed muscular differences. Generally, these involve the reduction in bulk of nuchal (nape) muscles. In the upright posture the head is more evenly balanced on the top of the vertebral column, so less muscle force is needed, whereas in a pronograde animal with large jaws the considerable torque developed at the base of the skull must be resisted by muscle force. The poise of the human head does pose other problems, and the detailed attachment and role of some neck muscles (e.g., sternocleidomastoid) are different in humans than in apes.

Muscles of the neck. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The consequences of an upright posture for the support of both the thoracic and the abdominal viscera are profound, but the muscular modifications in the trunk are few. Whereas in quadrupedal animals the abdominal viscera are supported by the ventral abdominal wall, in the upright bipedal posture, most support comes from the pelvis. This inevitably places greater strain on the passage through the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, the inguinal canal, which marks the route taken by the descending testicle in the male.

Differences are also seen in the musculature (the levator ani) that supports the floor of the pelvis and that also controls the passage of feces. The loss of the tail in all apes has led to a major rearrangement of this muscle. There is more overlap and fusion between the various parts of the levator ani in modern humans than in apes, and the muscular sling that comprises the puborectalis in humans is more substantial than in apes.

The muscular compression of the abdomen and the thorax that accompanies upright posture aids the vertebral column in supporting the body and in providing a firm base for upper-limb action. Anteroposterior (fore-and-aft) stability of the trunk is achieved by balancing the flexing action of gravity against back muscles that act to extend the spine. Lateral stability is enhanced by the augmented leverage provided to the spinal muscles by the broadening of the chest.