CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 3

BONES OF THE HUMAN ANATOMY

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 3

On average, the adult human skeleton contains 206 bones, which vary in shape, size, and composition. Each bone is designed to serve a specific purpose within the overall framework of the skeleton. These functions can include specific kinds of walking or throwing. They can also include protecting vital organs such as the heart and lungs. This chapter will explore bones and the purposes they serve.

The skull makes up the skeletal framework of the head and is composed of bones or cartilage, which form a unit that protects the brain and some sense organs. The upper jaw, but not the lower, is part of the skull. The human cranium is globular and relatively large in comparison with the face. In most other animals the facial portion of the skull, including the upper teeth and the nose, is larger than the cranium. In humans the skull is supported by the highest vertebra, called the atlas, permitting nodding motion. The atlas turns on the next-lower vertebra, the axis, to allow for side-to-side motion.

In humans the base of the cranium is the occipital bone, which has a central opening (foramen magnum) to admit the spinal cord. The parietal and temporal bones form the sides and uppermost portion of the dome of the cranium, and the frontal bone forms the forehead; the cranial floor consists of the sphenoid and ethmoid bones. The facial area includes the zygomatic, or malar, bones (cheekbones), which join with the temporal and maxillary bones to form the zygomatic arch below the eye socket; the palatine bone; and the maxillary, or upper jaw, bones. The nasal cavity is formed by the vomer and the nasal, lachrymal, and turbinate bones. In infants the sutures (joints) between the various skull elements are loose, but with age they fuse together. Many mammals, such as the dog, have a sagittal crest down the centre of the skull. This provides an extra attachment site for the temporal muscles, which close the jaws.

Fontanels are soft spots in the skulls of infants that are covered with a tough, fibrous membrane. There are six such spots at the junctions of the cranial bones. They allow for molding of the fetal head during passage through the birth canal. Those at the sides of the head are irregularly shaped and located at the unions of the sphenoid and mastoid bones with the parietal bone. The posterior fontanel is triangular and lies at the apex of the occipital bone. The largest fontanel, the anterior, is at the crown between the halves of the frontal and the parietals. It is diamond shaped and about 2.5 cm by 4 cm (about 1 by 1.5 in). The lateral fontanels close within three months of birth, the posterior fontanel at about two months, and the anterior fontanel by two years.

The zygomatic bone, also called the cheekbone (or malar bone), is diamond-shaped and lies below and lateral to the orbit, or eye socket, at the widest part of the cheek. It adjoins the frontal bone at the outer edge of the orbit and the sphenoid and maxilla within the orbit. It forms the central part of the zygomatic arch by its attachments to the maxilla in front and to the zygomatic process of the temporal bone at the side. The zygomatic bone forms in membrane (i.e., without a cartilaginous precursor) and is ossified at birth.

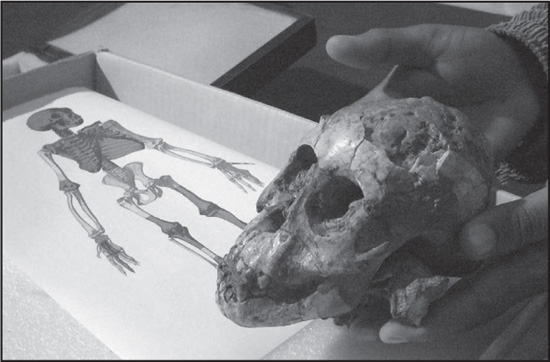

The parietal bone forms part of the side and top of the head. In front, each parietal bone adjoins the frontal bone; in back, the occipital bone; and below, the temporal and sphenoid bones. The parietal bones are marked internally by meningeal blood vessels and externally by the temporal muscles. They meet at the top of the head (sagittal suture) and form a roof for the cranium. The parietal bone forms in membrane (i.e., without a cartilaginous precursor), and the sagittal suture closes between ages 22 and 31. In primates that have large jaws and well-developed chewing muscles (such as gorillas and baboons), the parietal bones may be continued upward at the midline to form a sagittal crest. Among early hominids, Paranthropus robustus (also called Australopithecus robustus) sometimes exhibited a sagittal crest.

The occipital bone forms the back and back part of the base of the cranium. It contains the large oval opening known as the foramen magnum, through which the medulla oblongata passes, linking the spinal cord and brain. The occipital adjoins five of the other seven bones forming the cranium: at the back of the head, the two parietal bones; at the side, the temporal bones; and in front, the sphenoid bone, which also forms part of the base of the cranium. The occipital is concave internally to hold the back of the brain and is marked externally by nuchal (neck) lines where the neck musculature attaches. The occipital forms both in membrane and in cartilage; these parts fuse in early childhood. The seam, or suture, between the occipital and the sphenoid closes between ages 18 and 25, that with the parietals between ages 26 and 40.

Skull of a hominid (Australopithecus afarensis) child, estimated to be a three-year-old female, who died more than 3 million years ago. Lealisa Westerhoff/AFP/Getty Images

In human evolution, the foramen magnum has moved forward as an aspect of adaptation to walking on two legs, so that the head is balanced vertically on top of the vertebral column. Concurrently, the line of attachment of the nuchal musculature has moved downward from the lambdoidal suture to a point low on the back of the head. In precursors of humans, such as Australopithecus and Homo erectus, the nuchal markings, often heavy enough to form a protuberance, or torus, were intermediate in position between those in apes and those in modern humans.

The nasal conchae, also known as the turbinates, are thin, scroll-shaped bony elements forming the upper chambers of the nasal cavities. They increase the surface area of these cavities, thus providing for rapid warming and humidification of air as it passes to the lungs. In higher vertebrates, the olfactory epithelium is associated with these upper chambers, resulting in a keener sense of smell. In humans, who are less dependent on the sense of smell, the nasal conchae are much reduced. The components of the nasal conchae are the inferior, medial, superior, and supreme turbinates.

The vertebral, or spinal, column in vertebrate animals forms the flexible structure extending from neck to tail and is made of a series of bones, known as vertebrae. The major function of the vertebral column is protection of the spinal cord. It also provides stiffening for the body and attachment for the pectoral and pelvic girdles and many muscles. In humans an additional function is to transmit body weight in walking and standing.

Each vertebra, in higher vertebrates, consists of a ventral body, or centrum, surmounted by a Y-shaped neural arch. The arch extends a spinous process (projection) downward and backward that may be felt as a series of bumps down the back, and two transverse processes, one to either side, which provide attachment for muscles and ligaments. Together the centrum and neural arch surround an opening, the vertebral foramen, through which the spinal cord passes. The centrums are separated by cartilaginous intervertebral disks, which help cushion shock in locomotion.

The vertebral column is characterized by a variable number of vertebrae in each region, as well as by the way in which the column curves. Humans have 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 fused sacral, and 3 to 5 fused caudal vertebrae (together called the coccyx). The primary curve of the vertebral column in humans consists of three distinct sections: (1) a sacral curve, in which the sacrum curves backward and helps support the abdominal organs; (2) an anterior cervical curve, which develops soon after birth as the head is raised; and (3) a lumbar curve, also anterior, which develops as the child sits and walks. The lumbar curve is a permanent characteristic only of humans and their bipedal forebears, though a temporary lumbar curve appears in other primates in the sitting position. The cervical curve disappears in humans when the head is bent forward but appears in other animals as the head is raised.

The neck is the portion of the body that joins the head to the shoulders and chest. Some important structures contained in or passing through the neck include the seven cervical vertebrae and enclosed spinal cord, the jugular veins and carotid arteries, part of the esophagus, the larynx and vocal cords, and the sternocleidomastoid and hyoid muscles in front and the trapezius and other nuchal muscles behind. Among the primates, humans are characterized by having a relatively long neck.

The sacrum is a wedge-shaped triangular bone at the base of the vertebral column. It is located above the caudal (tail) vertebrae, or coccyx, and it articulates (connects) with the pelvic girdle. In humans the sacrum is usually composed of five vertebrae, which fuse in early adulthood. The top of the first (uppermost) sacral vertebra articulates with the last (lowest) lumbar vertebra. The transverse processes of the first three sacral vertebrae are fused to form wide lateral wings, or alae, and articulate with the centre-back portions of the blades of the ilia to complete the pelvic girdle. The sacrum is held in place in this joint, which is called the sacroiliac, by a complex mesh of ligaments. Between the fused transverse processes of the lower sacral vertebrae, on each side, are a series of four openings (sacral foramina). The sacral nerves and blood vessels pass through these openings. A sacral canal running down through the centre of the sacrum represents the end of the vertebral canal. The functional spinal cord ends at about the level of the first sacral vertebra, but its continuation, the filum terminale, can be traced through the sacrum to the first coccygeal vertebra.

Also referred to as the tailbone, the coccyx forms the curved, semiflexible lower end of the backbone (vertebral column) in apes and humans, representing a vestigial tail. It is composed of three to five successively smaller caudal (coccygeal) vertebrae. The first is a relatively well-defined vertebra and connects with the sacrum; the last is represented by a small nodule of bone. The spinal cord ends above the coccyx. In early adulthood the coccygeal vertebrae fuse with each other; in later life the coccyx may fuse with the sacrum. A corresponding structure in other vertebrates, such as birds, may also be called a coccyx.

The clavicle, also called the collarbone, is the curved anterior bone of the shoulder (pectoral) girdle in vertebrates. It functions as a strut to support the shoulder.

The clavicle is present in mammals with prehensile forelimbs and in bats, and it is absent in sea mammals and those adapted for running. The wishbone, or furcula, of birds is composed of the two fused clavicles, while a crescent-shaped clavicle is present under the pectoral fin of some fish. In humans the two clavicles, on either side of the anterior base of the neck, are horizontal, S-curved rods that connect laterally with the outer end of the shoulder blade (the acromion) to help form the shoulder joint; they connect medially with the breastbone (sternum). Strong ligaments hold the clavicle in place at either end. The shaft gives attachment to muscles of the shoulder girdle and neck.

The scapula, or shoulder blade, is either of two large bones of the shoulder girdle in vertebrates. In humans they are triangular and lie on the upper back between the levels of the second and eighth ribs. A scapula’s posterior surface is crossed obliquely by a prominent ridge, the spine, which divides the bone into two concave areas, the supraspinous and infraspinous fossae. The spine and fossae give attachment to muscles that act in rotating the arm. The spine ends in the acromion, a process that articulates with the clavicle, or collarbone, in front and helps form the upper part of the shoulder socket. The lateral apex of the triangle is broadened and presents a shallow cavity, the glenoid cavity, which articulates with the head of the bone of the upper arm, the humerus, to form the shoulder joint. Overhanging the glenoid cavity is a beaklike projection, the coracoid process, which completes the shoulder socket. To the margins of the scapula are attached muscles that aid in moving or fixing the shoulder as demanded by movements of the upper limb.

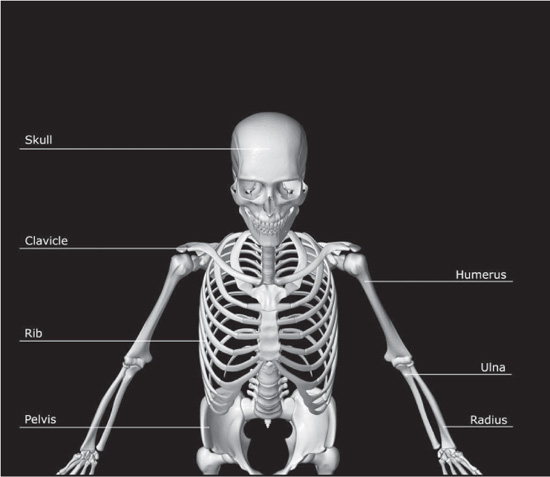

Major bones of the upper body. MedicalRF.com/Getty Images

Also known as the breastbone, the sternum is an elongated bone in the centre of the chest that articulates with and provides support for the clavicles of the shoulder girdle and for the ribs. Its origin in evolution is unclear. A sternum appears in certain salamanders. It is also present in most other tetrapods (four-legged animals) but lacking in legless lizards, snakes, and turtles (in which the shell provides needed support). In birds an enlarged keel develops, to which flight muscles are attached; the sternum of the bat is also keeled as an adaptation for flight.

In mammals the sternum is divided into three parts, from anterior to posterior: (1) the manubrium, which articulates, or connects, with the clavicles and first ribs; (2) the mesosternum, often divided into a series of segments, the sternebrae, to which the remaining true ribs are attached; and (3) the posterior segment, called the xiphisternum. In humans the sternum is elongated and flat; it may be felt from the base of the neck to the pit of the abdomen. The manubrium is roughly trapezoidal, with depressions where the clavicles and the first pair of ribs join. The mesosternum, or body of the sternum, consists of four sternebrae that fuse during childhood or early adulthood. The mesosternum is narrow and long, with articular facets for ribs along its sides. The xiphisternum is reduced to a small, usually cartilaginous xiphoid (“sword-shaped”) process.

The sternum ossifies from several centres. The xiphoid process may ossify and fuse to the body in middle age; the joint between the manubrium and the mesosternum remains open until old age.

Occurring in pairs of narrow, curved strips of bone (sometimes cartilage), the ribs are attached dorsally (in the back) to the vertebrae and, in higher vertebrates, to the breastbone ventrally (in the front). This arrangement produces the bony skeleton, or rib cage, of the chest. The ribs help to protect the internal organs that they enclose and lend support to the trunk musculature.

The number of pairs of ribs in mammals varies from 9 (whale) to 24 (sloth); of true ribs, from 3 to 10 pairs. In humans there are normally 12 pairs of ribs. The first seven pairs are attached directly to the sternum by costal cartilages and are called true ribs. The 8th, 9th, and 10th pairs—false ribs—do not join the sternum directly but are connected to the 7th rib by cartilage. The 11th and 12th pairs—floating ribs—are half the size of the others and do not reach to the front of the body. Each true rib has a small head with two articular surfaces—one that articulates on the body of the vertebra and a more anterior tubercle that articulates with the tip of the transverse process of the vertebra. Behind the head of the rib is a narrow area known as the neck; the remainder is called the shaft.

The humerus, the long bone of the upper arm, forms the shoulder joint above, where it articulates with a lateral depression of the shoulder blade (glenoid cavity of scapula), and the elbow joint below, where it articulates with projections of the ulna and the radius.

In humans the articular surface of the head of the humerus is hemispherical; two rounded projections below and to one side receive, from the scapula, muscles that rotate the arm. The shaft is triangular in cross section and roughened where muscles attach. The lower end of the humerus includes two smooth articular surfaces (capitulum and trochlea), two depressions (fossae) that form part of the elbow joint, and two projections (epicondyles). The capitulum laterally articulates with the radius; the trochlea, a spool-shaped surface, articulates with the ulna. The two depressions—the olecranon fossa, behind and above the trochlea, and the coronoid fossa, in front and above—receive projections of the ulna as the elbow is alternately straightened and flexed. The epicondyles, one on either side of the bone, provide attachment for muscles concerned with movements of the forearm and fingers.

The radius forms the outer of the two bones of the forearm when viewed with the palm facing forward. All land vertebrates have this bone. In humans it is shorter than the other bone of the forearm, the ulna.

The head of the radius is disk-shaped; its upper concave surface articulates with the humerus (upper arm bone) above, and the side surface articulates with the ulna. On the upper part of the shaft is a rough projection, the radial tuberosity, which receives the biceps tendon. A ridge, the interosseous border, extends the length of the shaft and provides attachment for the interosseous membrane connecting the radius and the ulna. The projection on the lower end of the radius, the styloid process, may be felt on the outside of the wrist where it joins the hand. The inside surface of this process presents the U-shaped ulnar notch in which the ulna articulates. Here the radius moves around and crosses the ulna as the hand is turned to cause the palm to face backward (pronation).

The ulna is the inner of the two bones of the forearm when viewed with the palm facing forward. The upper end of the ulna presents a large C-shaped notch—the semilunar, or trochlear, notch—which articulates with the trochlea of the humerus (upper arm bone) to form the elbow joint. The projection that forms the upper border of this notch is called the olecranon process. It articulates behind the humerus in the olecranon fossa and may be felt as the point of the elbow. The projection that forms the lower border of the trochlear notch, the coronoid process, enters the coronoid fossa of the humerus when the elbow is flexed. On the outer side is the radial notch, which articulates with the head of the radius. The head of the bone is elsewhere roughened for muscle attachment.

The shaft of the ulna is triangular in cross section; an interosseous ridge extends its length and provides attachment for the interosseous membrane connecting the ulna and the radius. The lower end of the bone presents a small cylindrical head that articulates with the radius at the side and the wrist bones below. Also at the lower end is a styloid process, medially, that articulates with a disk between it and the cuneiform (os triquetrum) wrist bone.

The hand is often described as a grasping organ. It is located at the end of the forelimb of certain vertebrates and exhibits great mobility and flexibility in the digits and in the whole organ. It is made up of the wrist joint, the carpal bones, the metacarpal bones, and the phalanges. The digits include a medial thumb (when viewed with the palm down), containing two phalanges, and four fingers, each containing three phalanges.

The major function of the hand in all vertebrates except human beings is locomotion; bipedal locomotion in humans frees the hands for a largely manipulative function. In primates the tips of the fingers are covered by fingernails—a specialization that improves manipulation. The palms and undersides of the fingers are marked by creases and covered by ridges called palm prints and fingerprints, which function to improve tactile sensitivity and grip. The friction ridges are arranged in general patterns that are peculiar to each species but that differ in detail. No two individuals are alike, and in humans the fingerprint patterns are used for identification. The thumb is usually set at an angle distinct from the other digits. In humans and the great apes it rotates at the carpometacarpal joint, and it is therefore opposable to the other fingers and may be used in combination with them to pick up small objects.

Among the apes and some New World monkeys, the hand is specialized for brachiation—hand-over-hand swinging through the trees. Digits two to five are elongated and used in clasping tree limbs; the thumb is reduced and little used in swinging. Terrestrial monkeys, such as the baboon, do not have reduced thumbs and can carry out precise movements with fingers and opposing thumb. The development of dexterity in the hands and increase in brain size are believed to have occurred together in the evolution of humans.

The several small angular bones that in humans make up the wrist (carpus) are known as the carpal bones. In horses, cows, and other quadrupeds, these bones consist of the “knee” of the foreleg. The carpal bones correspond to the tarsal bones of the rear or lower limb.

In humans there are eight carpal bones, arranged in two rows. The bones in the row toward the forearm are the scaphoid, lunate, triangular, and pisiform. The row toward the fingers, or distal row, includes the trapezium (greater multangular), trapezoid (lesser multangular), capitate, and hamate. The distal row is firmly attached to the metacarpal bones of the hand. The proximal row articulates with the radius (of the forearm) and the articular disk (a fibrous structure between the carpals and malleolus of the ulna) to form the wrist joint.

The tubular bones between the wrist (carpal) bones and each of the forelimb digits in land vertebrates are known as metacarpal bones. These bones correspond to the metatarsal bones of the foot. Originally numbering five, metacarpals in many mammals have undergone much change and reduction during evolution. The lower leg of the horse, for example, includes only one strengthened metacarpal; the two splint bones behind and above the hoof are reduced metacarpals, and the remaining two original metacarpals have been lost. In humans the five metacarpals are flat at the back of the hand and bowed on the palmar side; they form a longitudinal arch that accommodates the muscles, tendons, and nerves of the palm. The metacarpals also form a transverse arch that allows the fingertips and thumb to be brought together for manipulation.

The fingers, which also are called digits, are composed of small bones called phalanges. The tips of the fingers are protected by the keratinous structure of the nails. The fingers of the human hand are numbered one through five, beginning with the inside digit (thumb) when the palm is face downward.

The pelvic girdle, or bony pelvis, is a basin-shaped complex of bones that connects the trunk and legs, supports and balances the trunk, and contains and supports the intestines, urinary bladder, and internal sex organs. The pelvic girdle consists of paired hip bones, connected in front at the pubic symphysis and behind by the sacrum; each is made up of three bones—the blade-shaped ilium, above and to either side, which accounts for the width of the hips; the ischium, behind and below, on which the weight falls in sitting; and the pubis, in front. All three unite in early adulthood at a triangular suture in the acetabulum, the cup-shaped socket that forms the hip joint with the head of the femur. The ring made by the pelvic girdle functions as the birth canal in females. The pelvis provides attachment for muscles that balance and support the trunk and move the legs, hips, and trunk. In the infant, the pelvis is narrow and nonsupportive. As the child begins walking, the pelvis broadens and tilts, the sacrum descends deeper into its articulation with the ilia, and the lumbar curve develops.

When a human being is standing erect, the centre of gravity falls over the centre of the body, and the weight is transmitted via the pelvis from the backbone to the femur, knee, and foot. Morphological differences from apes include the following: the ilium is broadened backward in a fan shape, developing a deep sciatic notch posteriorly; a strut of bone, the arcuate eminence, has developed on the ilium diagonal from the hip joint (concerned with lateral balance in upright posture); the anterior superior iliac spine, on the upper front edge of the iliac blade, is closer to the hip joint; and the ischium is shorter. The pelvis of Australopithecus africanus, which lived more than 2 million years ago, is clearly hominid. Homo erectus and all later fossil hominids, including Neanderthals, had fully modern pelvises.

Sex differences in the pelvis are marked and reflect the necessity in the female of providing an adequate birth canal for a large-headed fetus. In comparison with the male pelvis, the female basin is broader and shallower; the birth canal rounded and capacious; the sciatic notch wide and U-shaped; the pubic symphysis short, with the pubic bones forming a broad angle with each other; the sacrum short, broad, and only moderately curved; the coccyx movable; and the acetabula farther apart. These differences reach their adult proportions only at puberty. Wear patterns on the pubic symphyses may be used to estimate age at death in males and females.

The femur, or thighbone, is the upper bone of the leg in humans. The head forms a ball-and-socket joint with the hip (at the acetabulum), being held in place by a ligament (ligamentum teres femoris) within the socket and by strong surrounding ligaments. In humans the neck of the femur connects the shaft and head at a 125 degree angle, which is efficient for walking. A prominence of the femur at the outside top of the thigh provides attachment for the gluteus medius and minimus muscles. The shaft is somewhat convex forward and strengthened behind by a pillar of bone called the linea aspera. Two large prominences, or condyles, on either side of the lower end of the femur form the upper half of the knee joint, which is completed below by the tibia (shin) and patella (kneecap). Internally, the femur shows the development of arcs of bone called trabeculae that are efficiently arranged to transmit pressure and resist stress. Human femurs have been shown to be capable of resisting compression forces of 800–1,100 kg (1,800–2,500 pounds).

The inner and larger of the two bones of the lower leg is known as the tibia, or shin (the other bone is the fibula). In humans, the tibia forms the lower half of the knee joint above and the inner protuberance of the ankle below. The upper part consists of two fairly flat-topped prominences, or condyles, that articulate with the condyles of the femur above. The attachment of the ligament of the kneecap, or patella, to the tibial tuberosity in front completes the knee joint. The lateral condyle is larger and includes the point at which the fibula articulates. The tibia’s shaft is approximately triangular in cross section; its markings are influenced by the strength of the attached muscles. It is attached to the fibula throughout its length by an interosseous membrane.

At the lower end of the tibia there is a medial extension (the medial malleolus), which forms part of the ankle joint and articulates with the talus (anklebone) below. There is also a fibular notch, which meets the lower end of the shaft of the fibula.

The fibula (Latin: “brooch”) forms the outer of two bones of the lower leg and was probably so named because the inner bone, the tibia, and the fibula together resemble an ancient brooch, or pin. In humans the head of the fibula is joined to the head of the tibia by ligaments and does not form part of the knee. The base of the fibula forms the outer projection (malleolus) of the ankle and is joined to the tibia and to one of the ankle bones, the talus. The tibia and fibula are further joined throughout their length by an interosseous membrane between the bones. The fibula is slim and roughly four-sided; its shape varies with the strength of the attached muscles.

The foot consists of all structures below the ankle joint: heel, arch, digits, and contained bones such as tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges. In mammals that walk on their toes and in hoofed mammals, it includes the terminal parts of one or more digits. The major function of the foot in humans is locomotion, and the human foot posture is called plantigrade, meaning that the surface of the whole foot touches the ground during locomotion.

The foot, like the hand, has flat nails protecting the tips of the digits, and the undersurface is marked by creases and friction-ridge patterns. The human foot is adapted for a form of bipedalism distinguished by the development of the stride—a long step, during which one leg is behind the vertical axis of the backbone—which allows great distances to be covered with a minimum expenditure of energy.

The big toe converges with the others and is held in place by strong ligaments. Its phalanges and metatarsal bones are large and strong. Together, the tarsal and metatarsal bones of the foot form a longitudinal arch, which absorbs shock in walking. A transverse arch, across the metatarsals, also helps distribute weight. The heel bone helps support the longitudinal foot arch.

It is believed that, in the evolutionary development of bipedalism, running preceded striding. Australopithecus africanus, which lived approximately 2 to 3 million years ago, had a fully modern foot and probably strode.

Bones of the human feet. © Superstock, Inc.

The tarsal bones are short, angular bones that in humans make up the ankle. The tarsals correspond to the carpal bones of the wrist, and in combination with the metatarsal bones, form a longitudinal arch in the foot—a shape well adapted for carrying and transferring weight in bipedal locomotion.

In the human ankle there are seven tarsal bones. The talus (astragalus) articulates above with the bones of the lower leg to form the ankle joint. The other six tarsals, tightly bound together by ligaments below the talus, function as a strong weight-bearing platform. The calcaneus, or heel bone, is the largest tarsal and forms the prominence at the back of the foot. The remaining tarsals include the navicular, cuboid, and three cuneiforms. The cuboid and cuneiforms adjoin the metatarsal bones in a firm, nearly immovable joint.

The several tubular metatarsal bones are located between the ankle (tarsal) bones and each of the hind limb digits. They correspond to the metacarpal bones of the hand.

In humans the five metatarsal bones help form longitudinal arches along the inner and outer sides of the foot and a transverse arch at the ball of the foot. The first metatarsal (which adjoins the phalanges of the big toe) is enlarged and strengthened for its weight-bearing function in standing and walking on two feet.

The toes are similar to the fingers in that they also are known as digits, they consist of small bones called phalanges, and the tips are protected by nails. However, in contrast to the fingers, the toes of the human foot, which is specialized for bipedal locomotion, are shortened and are relatively immovable and nonmanipulative.