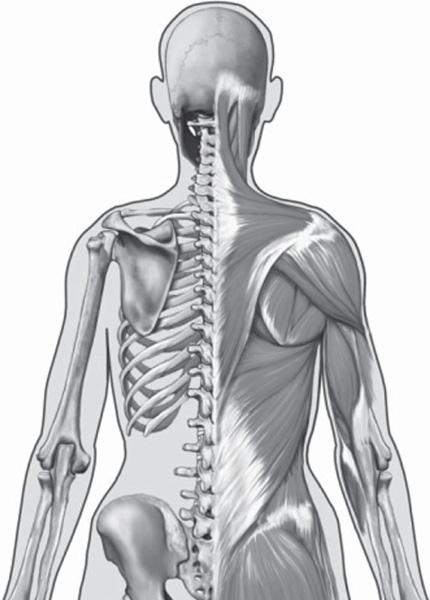

Bone and muscle do more than just hold a body together. They underlie every move, every touch, every step—in essence, every action undertaken. Even the inhalation and exhalation of life-sustaining breath is made possible by muscles that support the lungs, which are protected by the bones that comprise the rib cage.

This volume presents a detailed examination of the human skeletal system and related muscle systems of the human body. Using an easily understandable format, this book creates for the reader an accessible map of the skeletal system and the contributing musculature that enable motion and organ function.

The human skeleton provides support and protection for the body’s organs and facilitates movement by providing the framework for the arms and legs to swing free. All the bones in the body are connected by joints, some of which contain fluid and hence are mobile and permit complex motions such as twisting. While such features are common to many other members of the Animal kingdom, the human skeleton has several distinct features that are found only in the Primate order, the group to which humans belong. The specialized bones in the human hand, for example, enable the action of opposable thumbs, a trait that has played a vital role in allowing humans to grasp objects and to use tools.

As humans evolved, their bone structure and musculature began to change. Standing upright and the ability to travel bipedally are credited with forming the first major directional course in human evolution. Major developmental impacts to the human skeletal system brought on by the evolution of bipedalism included changes in the foot bone arrangement and size, hip size and shape, knee size, leg bone length, and vertebral column shape and orientation. The human spine developed an S-curved shape that acts as a shock absorber when standing upright, and helps to hold up the heavy skull. Walking on two feet also demanded monumental changes to the musculature of the upper and lower limbs, the head and neck, and the muscles of the trunk or torso. Such changes were required to support and maintain this new, upright posture.

This posture has provided humans with some distinct evolutionary advantages. Unlike chimpanzees, humans do not spend much time hanging from trees or otherwise using their hands for locomotion. Instead, bipedal movement freed the hands, allowing humans to use their hands to grasp tools and weapons, to build shelters, and to skin animals for clothes. As civilizations evolved, humans began to use their hands to create great works of art and to play instruments. This allowed humans to create a hand-mind connection that made their brains grow larger as well.

There are two primary types of bone material. Compact bone, which makes up 80 percent of all bone, is the dense, rigid outer layer of that provides strength and structural integrity. Cancellous bone, of which the remaining 20 percent is comprised, is honeycombed bone in structure and makes up much of the enlarged ends of the long bones and ribs. The structure of this type of bone enables it to absorb large amounts of stress.

The bones of the human skeleton are not static. The skeletal system is vibrant and continuously active, contributing a steady stream of new blood cells through bone marrow. Bone tissue is also subject to loss or damage through wear and tear, disease, or injury. Through the process of bone remodeling, bone tissue is constantly being dissolved, removed, and replaced by new building blocks of remodeled bone. Bone formation is affected by factors such as diet and hormonal influences and by a lack of nutrients, such as calcium and vitamins C and D. The absence of these nutrients from the diet can harm bone development.

Muscles aid in movement and protect and support the body. They also have an important role in automatic functions, such as breathing and digestion, and they provide a source of heat to keep the body warm. There are three major kinds of muscles: striated, smooth, and cardiac. Striated muscles are muscles that enable humans to move in various ways. They make up a large fraction of total body weight. Most of these muscles are attached to the skeleton at both ends by tendons, and they serve primarily to move the limbs and to maintain posture. Smooth muscle is found in the walls of many hollow organs, such as those of the gastrointestinal tract and the reproductive system. It does not have the striped appearance of striated muscle. Cardiac muscle, which is found only in the heart, is a special kind of muscle that contracts rhythmically. This rhythmic contraction allows the heart to pump blood through the body. Muscles perform a number of different functions in terms of allowing the human body to move freely. Extensor muscles, for instance, allow the limbs to straighten, whereas the flexor muscles allow the limbs to bend.

Joints permit humans to move in a variety of ways, from nodding their heads to flexing their knees. Joints, which consist of a variety of components, including cartilage, collagen, and ligaments, are specifically designed to be flexible. Flexibility gives joints such as the shoulder a wide range of motion. There are two basic structural types of joints—diarthroses (fluid-containing joints) and synarthroses (characterized by the absence of fluid). Synarthroses are located in the skull, the jaw, the spinal column, and the pelvic bone, and they perform highly specialized functions. They allow for infant skull compression during childbirth, which eases the infant’s passage through the birth canal, and they allow the hip bones to swing upward and outward during childbirth. They also allow for vertebrae to compress during physical activities, and they act as virtual hinges in the skull, allowing for the growth of adjacent bones. Diarthroses are much more varied in their structure and assigned tasks, and they are primarily responsible for movement and locomotion. The joints of the elbows, knees, and ankles are all examples of diarthroses.

It is important to note the relationship of injury and disease when examining the skeletal system, muscles, and joints. Injury to bone, such as a fracture, can lead to the onset of disease within that bone. On the other hand, disease within a bone, such as osteoporosis, can contribute to bone fractures. The leading contributor to bone injury and fracture is abnormal stress on the bone tissue. This can occur as a result of physical exertion, a fall, or pressure upon the bone in a nonsupported direction. Inactivity can also cause fractures. For instance, in a patient who is bedridden, bone formation is reduced, weakening bone tissues. If a patient receives radiation to fight cancer, that same radiation can have a negative impact on bone strength and integrity. Bone tissue is also subject to infection, such as when microorganisms are introduced into the tissue through the bloodstream or when a fractured bone breaks the surface of the skin. The skeletal system can also exhibit developmental abnormalities, such as scoliosis, or curvature of the spine. Several cancers can affect bone tissue as well.

The most common indications of muscle disease or injury are pain weakness, and atrophy (a noticeable decrease in size of the affected muscle tissue). By definition, muscle weakness is the failure of the muscle to develop an expected rate of force. Muscle weakness can be caused by disease of the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves, since these conditions may interfere with the proper electrical stimulation of the muscle tissue. In addition, a defect within the muscle tissue itself can give rise to weakness. There are several classifications of muscle weakness. Motor neuron disease, also known as Lou Gehrig disease, is characterized by the degeneration of neurons that regulate muscle movements. The neurons eventually atrophy, causing the affected muscle tissue to waste away. Some of the most well-known muscle diseases include muscular dystrophy, which causes degeneration of the skeletal muscles; myasthenia gravis, a chronic autoimmune disorder caused by failure of nerve impulses; and myositis, inflammation of muscle tissue.

Joint diseases fall into one of two categories; they are either inflammatory or noninflammatory. Arthritis is a generic term for inflammatory joint disease. Inflammation causes swelling, stiffness, and pain in the joint, and often fluid will accumulate in the joint as well. Examination of any such fluid can be a critical clue in establishing the nature and cause of the inflammation. Bacteria, fungi, or viruses may infect joints by direct contamination through a penetrating wound, by migration through the bloodstream as a result of systemic infection, or by migration from infected adjacent bone tissues. These joint inflammations are classified as infectious arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis, which is similar to infectious arthritis except that no causative agent is known, typically affects the same joints on both sides of the body. The fingers, wrists, and knees are particularly susceptible to this form of arthritis. Symptoms include joint stiffness upon waking, fatigue and anemia, an occasional slight fever, and skin lesions outside the joints. In roughly one-third of patients, the condition progresses to the point where joint functionality is totally compromised.

Noninflammatory joint diseases include degenerative joint disorders and blunt force injuries varying in intensity from mild sprains to fractures and dislocations. A sprain involves damage to a ligament, tendon, or muscle following a sudden wrench and partial dislocation of a joint. Traumatic dislocations must be treated by prolonged immobilization to allow supportive tissue tears in muscles and ligaments to heal. In the case of fractures in the vicinity of joints or fractures that extend into the joint space, it is imperative that the normal contour of the joint be restored. If the joint is not repaired correctly, long-term arthritic complications may develop.

There are many different types and causes of degenerative joint disease. From the simple, ubiquitous disorder osteoarthritis that affects all adults to a greater or lesser degree by the time they reach old age, to joint abnormalities such as hemarthrosis (bleeding into the joints), all are defined, explained, and made understandable within this body of text.

This volume presents an exceptional tool and is a meaningful addition to the library of anyone who is making a study of anatomy and medicine.