1

1

It was quite a row she had with her mother and, like many a dutiful daughter, she regretted it the next day. Still, she did not want to stay at the family home at Seaham in County Durham for the social season. She was nineteen, months short of twenty, and loved her London, no matter that two years before, she made disparaging remarks about her own “coming out” there.

Anne Isabella Milbanke, always called Annabella, was born on May 17, 1792, to middle-aged parents who had long since given up hopes of having a child. Judith thought she was going through menopause at first, but she was still months shy of forty and in good health. As her old aunt Mary Noel told her, the common notion about change of life was that it began thirty years after the first period “and I think you were sixteen at least when it began.” Old Aunt Mary had been a mother to Judith and knew she was pregnant before Judith did. Judith’s brother, Lord Wentworth, was pleased as well when pregnancy was confirmed, for now he would have a legitimate heir and couldn’t help wishing, truth be told, for a boy. Still, when Annabella was born, he celebrated with Annabella’s good-looking and good-natured father, Sir Ralph, and his favorite and oldest sister, Judith. Lord Wentworth was going to have women, first Judith, then his niece Annabella, as heirs. Women could inherit in his line. Better than nothing—much.

Annabella’s parents were unusual for the times. They were fashionable people, belonged to the ruling class, yet theirs was a love match and neither took lovers—hardly the rule in the eighteenth century or during the Regency that followed. They hobnobbed with royalty. Annabella’s first name, Anne, was that of her royal godmother, the Duchess of Cumberland. They went to balls, gave dinners, and spent every season in London at their home at Portland Place, as Sir Ralph became a Member of Parliament two years before Annabella’s birth and remained such for twenty-two years, right up to 1812, the winter of the row.

Annabella’s parents were unusual as well for raising their own daughter. Not that there wasn’t help, and from an early age Mrs. Clermont was always there, even sleeping in Annabella’s room on the scant occasions when Judith had to be away from home. Judith appreciated the fashionable life she had led, the grand tours, the spas, the balls, the London seasons, the ton. But once she had a child, she no longer traveled to London with Ralph when Parliament was in session. In her forties she simply preferred being with her child. Annabella, she wrote, grew more precious, precocious, and amusing every day. And their comfortable home in Seaham was by the sea, which both mother and daughter loved—and who could doubt the benefits of sea air? Annabella grew healthy, balanced, strong. Her first ballet master couldn’t get over her immediate grace, drive, ability to learn. Such a report pleased the mother. There was truth to it as well.

When Ralph and Judith traveled together, they also brought the child and, in those early years, only accepted invitations to homes at which young children were welcome. This was so unusual that it must have sent some tongues wagging. There was probably no such phrase in the late eighteenth century, but the Milbankes were a tight-knit family.

By the time Annabella was six, she was old enough to be brought to London for the Parliamentary season. London was love at first sight for Annabella, just as the sea had been when she was an infant. A few years later her father set up an allowance for her of 20 pounds a year, to be delivered quarterly by a Mr. Taylor, and for which the child would fill in a receipt. She would save almost all to spend when she was in London. Though Seaham would always be the home of her heart, it wasn’t London. And particularly in 1812, when she was a young woman close to twenty, with friends galore in town, she didn’t want to spend the season in the north country with the old folk.

The circumstances were these. Her father Sir Ralph, whom she adored, was not well and was about to give up his parliamentary seat. A Whig, and of the most progressive part of that party, he had back-benched it through his whole career. As much as his daughter loved him, she knew he was not meant for the world. In his sixties, he was ruddy-faced and good-natured, given to tell (repeat) a story, help a neighbor, drink and eat too much. He had a poetic streak, and he and Annabella teased each other, told jokes, especially when they both were a bit tipsy. There was something grandfatherly in his love.

He was all for his neighbors in Durham, the region he represented. Soon, in retirement, he would work on improving sanitary conditions there. They loved him in Durham. But in the wider world of affairs, he was considered genial and ineffectual. Annabella herself described him as an Uncle Toby, but with many more qualities and depth. In 1812 he wasn’t well at all, most probably an acting-up of his gout. This ill health might have been exacerbated by financial worries. It was rumored he had ruined himself with these many expensive runs for Parliament. There had also been bank failures, problems on his estates, Napoleon. Earlier, he even had to sell some land at the bottom of the market. February of 1812 was not Sir Ralph Milbanke’s finest hour.

Wife Judith was made more for the world. She was quick, sharp, understood politics and science and the dark side of human nature. She could keep accounts, run an estate. She was up to date, believed in inoculating infants—Annabella had been inoculated. Judith offered to pay for anyone on her estates or in the region who would have their child inoculated as well. No one took her up on it. She was extremely progressive, against war with France, adamantly antislavery. She made speeches on the hustings for her husband. Annabella attended as a child and wrote that her mother was more effectual than her father, adding that of course a woman making public speeches was an event in itself.

The sharpness of Annabella’s mind, her brilliance in mathematics and science, her ability to speak plainly and well, owe something to her mother. Perhaps the streak of poetry in her, the love of classic learning and languages, come from her father. From both she received what she would practice all her life: “zealous” attention “to the comfort of the labouring poor.” The best doctors attended their tenants, the “finest Claret” selected for them when sick. “I did not think that property could be possessed by any other tenure than that of being at the service of those in need.” This would turn into a philanthropy notable throughout her life.

Still, Judith was always hovering, wanting the best for her daughter, concerned she was too idealist. She wished for a good marriage. In that quarter Judith might have had less concern than she evidenced. For Annabella at nineteen had close to a battalion of suitors. She had grown up to be as graceful as she had been as a child. She had long, rich brown hair and blue eyes. She was small and well formed and had a remarkable texture and glow to the very fair skin of her rounded face. Added to this, she was a prodigy in mathematics and languages, and rather than speaking in lisping fashionable slang, she spoke her mind straight out with no airs at all. Her lineage stretched back to Henry VII and one day she would be a baroness. During the previous season in London she had refused the hand of many of the most eligible men in England—some of whom never married afterward. She wasn’t beautiful, but she was very pretty, and with her strong mind, moral views, and intelligence added to her prospects, she was enthusiastically sought after. She was kind, she appeared calm, and perhaps more than one man—and his mother—understood that in an age when fine superficialities abounded, she was quite uniquely herself.

She was also used to getting her own way. Going to London, an unmarried girl, alone? Judith objected. Leaving when her father was ill? Adding concern to her mother?

Of course she wouldn’t be alone. A dear family friend, the older Lady Gosford, was most desirous of Annabella staying at her home. And another, Mary Montgomery, Annabella’s closest friend, was in London. MM, as she was always referred to in Annabella’s letters, was an invalid with all sorts of health problems, including a very bad back. Annabella didn’t know how long she would survive, and she wished to be a comfort to her during these sad days. (Ironically, MM would be the only one of Annabella’s early circle who would outlive her.)

Annabella regretted her row with her mother and confided in a family friend, Dr. Fenwick, who had been with her when she had scarlet fever as a child. He wrote that if she felt she had any fault in her conduct toward her mother she should repent it: “I know you have a warm temper to struggle with; I have seen you subdue it & have been sensible of the effort it cost you.” Annabella took his advice and had a calmer talk with her mother. After it, she wrote a letter to Judith, on February 9, admitting she was well aware her mother’s concerns were not self-involved, but stemmed from fears for Annabella’s safety. She knew she shouldn’t leave Seaham until her father’s health was improving, or else she would be flying from “one anxiety to suffer from another.” She would wait a fortnight to make sure her father was making progress: “I cannot express how calm & contented my mind has become since your kindness last night,” she ended her letter, allowing one to assume her mother had already more or less given way to her headstrong daughter.

So on February 21, Annabella left Seaham to go to London, for the first time without her parents in tow. She wrote to her mother not to worry. “If I should die,” she had already equipped her maid with “fifteen pens” with which to let Judith know instantly. Meanwhile, she ate heartily on the road, and when she got to London she was in fine health and thought she never looked better. MM perked up when she saw Annabella, but who knew how long improvement would last. And Annabella let her parents read over her shoulder, as she had in 1812 a brilliant social season.

“I am quite the fashion this year,” she wrote home, sharing her experiences in letters audacious, energetic, joyful. Not only was she coming into her own, but she had an audience of two to whom she had to prove her maturity, at the same time knowing her every encounter and thought would be of interest to them. Ah, to be young, invulnerable, and the apple of one’s parents’ eye. It lasts only for a moment, but given the censure she received from some later scholars for her youthful exuberance and self involvement, one wonders—had they never been nineteen? Or popular?

The suitors—and their hopeful parents—seemed to meet Annabella the minute she stepped off her coach. There was a General Pakenham, who was in his thirties and amused her with stories of his brother-in-law Lord Wellington—she refused him, hoping they could still be friends. There was Augustus Foster, the son of the present Duchess of Devonshire’s first marriage. “An icicle,” the Duchess, who had earlier been the Duke’s mistress, would come to call Annabella for refusing her son. Annabella had no intention of marrying beneath her station, or adding to the financial woes of her father. Lord Jocelyn was as warm as he was funny-looking. He was an heir and she liked him. His previous engagement was broken off when his fiancée realized “insanity is very strong in the family.” Enough said. There was William Bankes, also an heir and a Cambridge friend of that young poet Byron: “Mrs Bankes visited me the day before yesterday, in order to make an oration on the merits of William my suitor.” Another source leaked that “the youth had £8,000 per an, independent of his father whose heir he must be.” She obviously thought that would amuse “Sir Ralph,” as she sometimes called her father.

Womenkind considered her “somebody,” she confided. She thought about it and came to the conclusion, “without jest,” that she was liked more in company than on an individual basis as “I am stronger and more able to exert myself in the scenes of dissipation.” One doubts she meant that she could drink anybody under the table, more that she spoke her mind, was herself and, as the mountain was constantly coming to Mohammed, she certainly didn’t flirt—or need to.

Things were going so well that she decided, early on, to open her parents’ house on Portland Place for an evening in order to give a dinner party for fourteen. Her uncle Wentworth and his wife would be in town, and she jested that “the admirable manner in which I shall do the honors of the House may procure me a wing of the estate.” Though she joked about the future inheritance, she certainly knew how to get her mother “to approve this extravagance.”

She hadn’t called on her father’s only sister when she arrived, but almost immediately bumped into her at a ball. So on March 2 she felt it her duty to call at Melbourne House, though her aunt, Lady Melbourne, had ignored her brother’s illness. Hadn’t sent Sir Ralph a word.

ELIZABETH MILBANKE, unlike brother Ralph to an extraordinary degree, had left the north country as soon as she could, married the very wealthy, extremely undistinguished Lord Melbourne when she was sixteen, and headed to London. Tall for her times, strikingly attractive and sensual, brilliantly malicious, Lady Melbourne became a political force through the powerful men she drew to her, becoming the most influential Whig hostess of the day. (No back-bencher she.) She resembles, in her friend Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s play School for Scandal, Lady Teazle, who came from the country and learned how to get the upper hand of her husband, informing him that ladies of fashion in London were accountable to no one after they married. The current saw was that a woman of fashion owed her husband an heir of his own blood, and after that first son she was free to suit herself. Lady Melbourne complied.

Annabella and her parents knew the rumors about Ralph’s sister were true, that after first son, Peniston, each of her successive five children were by a different man, from intellectual aristocratic to the Prince Regent. “Prinny,” as the future George IV was called, had an affair with Lady Melbourne that resulted in many perks for her husband as well as in a fourth son (George). During the Regency, it was Judith’s and Ralph’s fidelity that was “odd.” There were so many children carrying the noble names of men who were not their biological fathers that they were called “children of the mist.”

Lovers to one side, Judith simply didn’t trust her fashionable sister-in-law, though she could never convince her husband that his sister disrespected him and that she begrudged Annabella’s birth. Annabella’s sudden and late arrival robbed Lady Melbourne of a paternal inheritance she thought would come down to her. The families were not close. In hindsight, one might wish “If only.” If only it had stayed that way. But it didn’t. Annabella’s subtle aunt came to play loose and free with her niece’s fate.

Lady Melbourne’s intelligence, sensuality, and intense ambition for her children, her very worldliness and ability to please the men who were important to her, were one side of her character. She was also a practical woman much like sister-in-law Judith, who knew about farming and improving estates. It was joked that she was the only woman in London able to make a profit from her garden. She was given a less kindly botanical nickname “the Thorn” for the prick of her tongue, and there were those who said there wasn’t a happy marriage she could abide. She and her friends, such as the earlier Duchess of Devonshire, Georgiana, were often grist to the newspapers of the day. She knew the world, was charming, dangerous, manipulative, glamorous, bigger than life. She and her brother’s family did have one trait in common: an unusually hearty appetite. There was not a Milbanke or Melbourne who picked at food. They gobbled chops. Annabella never referred to fashionable clothes but to many a meal in her letters. Lady Melbourne was sixty-two years old and still attractive. That morning in March, however, when she greeted Annabella, her head was shaking as if she had some sort of paralytic episode. Her niece, who understood anatomy and medical symptoms, reported this home—to a mother who also understood anatomy and medical symptoms. Her aunt’s health might offer some excuse for her having failed to inquire after her brother, Annabella opined. A few weeks later we find a reluctant Annabella dining at Melbourne House en famille. At that dining table were two more who would become enmeshed in her drama. One was Lady Melbourne’s particular favorite, her second son, and Annabella’s first cousin: William Lamb, living on the first floor of his parents’ mansion with his wife Caroline (number two).

William, who was attracted to young girls, knew his wife Caroline in the days when she was a child and he seemed to form an attraction to her early on. They married when she was twenty. Thin, boyish, with a freckled nose and reddish blond hair, Caroline was some six years older than cousin Annabella. Raised in the lap of luxury, “Caro,” as she was called, was bright, talented, and hugely unstable. We’d call her “bipolar” today. When she was a child, her aristocratic and adored grandmama, Lady Spencer, diluted opium into lavender to calm her down.

Annabella reported home: “Caroline seems clever in every thing that is not within the province of common sense.” There was a golden cord of propriety that ran through these freewheeling Regency lives. One did what one wanted—discreetly. Discretion Caroline lacked. In the past, Annabella considered Caroline “silly.” What she realized at that dinner was that the silliness wasn’t a byproduct of Regency artificiality, but instead part of Caroline’s hyperactive personality. She was no fool, though she certainly could be foolish. What was to stop her from indulging her whims? Her life was buttressed by footmen and servants. Caroline would later blame the wealth and privilege into which she was born for her recklessness.

William was tall like his mother, a dark, handsome man in his early thirties. His mother was ambitious for him. He had the finely tuned intelligence her husband lacked. His biological father, Lord Egremont, “was the pattern grand seigneur of his time,” according to biographer David Cecil. “Egremont spent most of his time at his palace of Petworth in a life of magnificent hedonism, breeding horses, collecting works of art, and keeping open house for a crowd of friends and dependents.” He didn’t marry until late in life because of Lady Melbourne’s influence. He was restless, genial, and almost surprisingly erudite, characteristics shared by his biological son William, who often dropped by the palace for a visit.

William loved the child in his wife and probably would have married her earlier if he had had anything to offer her, but he was a second son. Here, fate took an ironic turn. Peniston Lamb, Lord Melbourne’s firstborn, died of tuberculosis. Suddenly, William became heir. Lord Melbourne took out his profound grief in rage and by the means he had at his disposal. Whereas Peniston had received a yearly allowance of 5,000 pounds, Melbourne retaliated by allowing his son-in-name-only, 2000. Didn’t give a damn that such a slight could not go unnoticed. Glad of it. Usually, Lady Melbourne could have her way with him—his attentions were habitually elsewhere. But his anger and grief were so overwhelming that she dared not try. William’s prospects, though, had suddenly shifted. Now first son and heir, he married the girl he was attracted to when she was fourteen and he twenty-one. Years later, when William became Lord Melbourne, the teenaged Queen Victoria’s first Prime Minister, and adored mentor, he and Annabella would be friends who shared, as others couldn’t, the pain and knowledge of the past.

At this intimate family dinner, however, Annabella was not at all impressed by lanky, handsome, loud-laughing William, thought him self-involved in his informality. Caroline, on the other hand, showed surprising consideration, Annabella wrote to her mother.

Caro, or Caro William, as she was called, was giving a small party that week and invited Annabella, with the caveat that Lady Holland would be there. Perhaps her mother would not want her to attend? Lady Holland was a divorcee, and though all of male Whig London dined at Holland House, known for its brilliant conversation and political influence, the Lady was not widely accepted socially. Wasn’t that considerate of cousin Caro, Annabella wrote to Judith. She had responded—and here breeding shows—that she would not object to being in the company of anyone Caroline saw fit to receive as a guest, though, of course, if she was asked to be introduced to Lady Holland, she’d refuse. She was sure her mother would agree “no one will regard me as corrupted by being in the room with her.” With that, Annabella answered for her mother and, discreetly, went her own way.

After the party, Caroline invited her cousin to a bigger one she was giving at Melbourne House on 25 March 1812. Annabella accepted. An exciting occasion indeed; the man of the hour would be there. At cousin Caroline Lamb’s fashionable, slightly risqué morning waltz (for waltzing had just arrived from Vienna and was considered improper by some in the ton), Annabella Milbanke first laid eyes on Lord Byron. It was also the first season women danced in men’s arms.

THREE WEEKS PREVIOUSLY, twenty-four-year-old Lord Byron awoke to find himself famous. His book-length poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage had just come off the press, yet already two editions had sold out. Editions were small in those days. Still, the first copies were eaten up, leaving an appetite for more. His fame spread like wildfire—a literary contagion unlike any that had come before. Caroline had read the poem in proofs and raved. It was all people spoke of; Annabella caught up, reading Childe Harold a few nights before the morning waltz.

John Murray, his publisher, had urged Byron to cut some of his most savage satire, particularly concerning religion and politics. The sex, perhaps Murray knew, would sell. But Byron refused, just as, though he was in terrible financial straights as usual, he passed his royalties on to another. A poet should not accept money for his poetry, something he accused Walter Scott of in an angry satire, “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers,” written three years previously when his early work was badly reviewed. Important as well, he considered himself, first and foremost, an aristocrat. His dysfunctional family traced back to Norman times—and he had inherited an abbey at Newstead to prove it. A Lord Byron didn’t work for a living—neither did his untitled father Mad Jack, who fleeced two wives amid other scandals before he died.

In truth, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage was a thinly disguised self-portrait of a brooding young aristocrat-in-training (for that’s what “Childe” meant in medieval days), and its unflinching realism, delicious wit, and carnal exploits caused a sensation. The blatantly autobiographical elements heightened the fervor. That it was Byron’s story was undeniable—at first he thought to title the poem “Childe Burun,” using the medieval form of his own family name. His revealing depiction of a young man “sore given to revel and ungodly glee” fleeing in exotic, picturesque travel from the sexual adventures of his misspent youth turned him into something new. He was now not only a poet and a lord, he was a “celebrity,” the very first of the ilk. That Byron was exceptionally handsome with his dark hair, grey eyes, dark moods, and unpredictable nature added to his glamour. So did his strong plea for the national independence of enslaved nations in Childe Harold and his scathing rant against Lord Elgin for stripping the Parthenon of its sculptures and sending the plunder home as his marbles. Byron’s fame brought him swift entrance into the highest level of Regency society. Aristocrats who hadn’t paid attention to him previously, now lisped their fashionable baby talk his way.

Byron didn’t waltz. At Caroline’s fete at Melbourne House, one can picture him leaning against a fine drawing room mantle, most likely designed by Chippendale—once Lady Melbourne’s favorite. Byron often leaned against mantels and let the world whirl while he observed. He was very sensitive about his lameness. His right foot was deformed, the calf of that leg withered, the leg itself shorter than the other. The handsome, brooding poet loped along, adding even more dark romance to his persona, but adding nothing to his sense of self. He never forgave or forgot his cursed deformity. When he was a child, his mother put him through all sorts of excruciating fittings and crampings and cures that didn’t work. He was an agile swimmer, and raised hell at school, but of course, his lameness made him red meat—even for boys who liked him. Imagine the transformation at the age of ten, when lame, plump George Gordon suddenly came into his title. One day boys teased, headmasters threatened, the next day they bowed, they flattered. Lord Byron’s fate, as his nature, lay in extremes.

Annabella watched the women at Caroline’s morning waltz throwing themselves at Byron. She had written home of having read his poem, finding in it deep feeling and some mannered expression. In London that season, she had already met the movers and shakers of the day, so many that she was rather bored by them and didn’t spend much time discussing them in her letters. But Byron! Everyone was abuzz. In her youth she had created her own magazine for her family at Seaham; now she had the human interest story of the season to report to her adoring parents: “All the women were absurdly courting the author of Childe Harold, and trying to deserve the lash of his Satire.” She, on the other hand, had no desire to be portrayed in one of his poems and refused the chance to be introduced to the man who had all London at his feet. He was cynical, she wrote, she saw it in the twist of his mouth, and she perceived an anger burning within him, what she called “the violence of his scorn.” He attempted to control it—often by bringing hand to his curling lips as he spoke. For herself, she couldn’t “worship talents” that were unconnected with respect for one’s fellow man.

Cousin Caroline’s impressions were more pithy. In her diary Caroline Lamb wrote that the moody poet was “mad, bad and dangerous to know,” encapsulating the young Byron for posterity. Then she quickly jumped into an outrageous affair with Byron, outrageous not that she had an affair, but that she knew no boundaries in her sexual pursuit of him. If there hadn’t been a Byron, Caroline might have invented one. She had found the objective correlative for her hyperactivity and constant need of attention.

Annabella had previously spent a weekend with cousin Caroline at the Melbourne country retreat at Brocket Hall and wrote home that Caroline didn’t do justice to the strength of her intellect, hiding it behind a childish manner that “she either indulges or affects.” That “childish” facade that Annabella perceived was Caro’s luck, in a way. For it was the child in her that found its way into her husband’s heart, the child he could indulge and, later, could not totally abandon.

Caroline cut her short hair even shorter, donned her Page attire—she enjoyed cross dressing—and slipped past servants into Byron’s bedroom. She also mailed Byron curls of her pubic hair and asked for “blood” in return: “I cut the hair too close & bled much more than you need.” For at least four months Byron fell madly in love himself, and the two exchanged over three hundred, mainly lost, letters. He found her bohemian, quixotic nature unique among womankind, and most probably, in her ambiguous sexuality and outrageous disregard for the mores of her class, he saw himself.

The talented, erratic, erotic, and married Caroline Lamb would enter Lord Byron’s bedroom disguised as a page.

As early as the morning waltz, Annabella witnessed Caroline flirting with Byron, trying to imitate his gestures, and was inspired to write a short poem of her own, naming “Caro” outright as she portrayed her cousin’s “silliness,” as well as that of the many other women who crowded and crowed about Byron. They all smiled and sighed over Byron, hoping to imitate each of his strange grimaces and to replace them with “a wilder Passion.” Was human nature to be cast anew because of this man, she wondered, in Byronmania:

Then grant me, Jove, to wear some other shape,

And be an anything—except an Ape!!

Annabella would make “no offering at the shrine of Childe Harold,” she had assured her parents, adding, however, that she would not refuse his acquaintance should it come her way on a less hectic day. Lord Byron came Annabella’s way the next month, but not before another party at which she astutely observed that Lord Byron was actually very shy. Annabella would have all through her life a most uncanny instinct for the psychology of others, particularly when she kept the other at arm’s length. When she came too close, it became her conviction as she grew older and wiser, it was she who got burned.

Byron’s shyness, coupled with the annoying presence of William Bankes, that suitor she could not shake off, kept her from intruding on his privacy. However, the very next night, the two met at a supper party and spoke to each other for the first time. Interesting conversation. How handsome he was. How noble his manners. Still, he didn’t have that “calm benevolence” she was looking for in a husband. Even without it, his conversation became the best she ever knew as the season progressed. It took her a while to arrive at a less articulate version of cousin Caroline’s “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.”

“I think of him that he is a very bad, very good man,” Annabella informed her parents, artlessly, accurately. Her empathy for him had swelled. She overheard him at a party abruptly asking those about him, with his usual abandon, “Do you think there is one person here who dares look into himself?” Though those words echoed her feelings about fashionable London, they didn’t “bind” her to him. It was what followed: “I have not a friend in the world,” he proclaimed. He knew all London sought him out for his fame, that these people were moths to his talent, and that the women of the bon ton were curious to bed him. The rumor that he was extraordinarily well endowed did not detract from his charms.

Annabella was different. (Or thought she was. Cousin Caroline had been attracted by the poet’s claim of friendlessness, as well as by his other attributes.) There and then, in a sudden rush, Annabella made a secret vow to herself: She would silently, in her heart of hearts, be Lord Byron’s devoted friend: “He has no comfort but in confidence, to soothe his deeply wounded mind.” If her disinterested friendship could offer him “any temporary satisfaction” from his obviously troubled state, wasn’t it almost a Christian duty to comply? Not that she’d seek to be more than a friend: “He is not a dangerous person to me,” she wrote to her alarmed parents.

From their first meeting there seemed to be a spontaneous understanding between Annabella and Byron—often they seemed not to need words. “It is said,” she would write, “that there is an instinct in the human heart which attaches us to the friendless.” Jove had indeed granted her another shape. For Annabella, friendship was not fawning acceptance, but honest exchange. She would hold to this through her life—that she had been and always would be Byron’s true friend. Of course, in the fullness of time, she’d recall that when she made her girlish vow: “I did not pause—there was my error—to enquire why he was friendless.”

That season, she spoke with Byron one human being to another. If she didn’t agree with him, she told him what she thought. She was the antithesis to Caroline, who was causing scenes, threatening destruction, burning facsimiles of his letters around a fire at Brocket, servants in tow. The next season, when Caro cut her hand at a ball while wielding jagged glass at him, running out in hysterics, blood splattering her fine dress, her antics hit the papers. Caroline couldn’t or wouldn’t control herself. As intrigued as Byron had been by her rashness, unconventionality, and sexual ambiguities, Byron couldn’t control her either.

It might have been quite refreshing for him to be with Annabella, this accomplished young woman, who swatted off suitors like flies (some of whom, like Bankes, were his friends), could speak intelligently on everything from the Greek historians to the parallelogram, who took an honest interest in him as a human being, and didn’t seem inclined to jump into bed. There were times when Caroline’s unbridled sexuality went beyond him. Frightened him? In Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage he bemoaned the death of his one true love—actually John Edelston, a choirboy at Cambridge.

Byron’s homosexuality did not end with his years at Harrow. John was also the model for Byron’s love poems to Thyrza, three of which were appended to the first edition of Childe Harold, though he changed John’s sex for public consumption. Leaning against one mantel or another, watching graceful Annabella, surrounded by her own entourage of admirers, abounding in moral ideals, talking sense on many a subject without any airs at all in a society that doted on affectation, he might have felt quite safe—sexually that is. Byron didn’t pursue women; they pursued him: mainly older, married, experienced women.

Annabella might have felt safe as well, clad in the armor of friendship and knowing Byron was bedding her cousin. Caroline warned her, rather shrewdly, to “shun friendships with those whose practice ill accords with your Principles.” Warned her that if she succumbed to Byron she was tossing herself into stormy seas. She had intuited that her mad, bad lover seemed to fancy her country cousin—especially when he was positive about poems Annabella sent him for criticism. Byron might have meant his praise—or at least have been surprised by the subject matter. Annabella’s early poems could be moody and dark and deal with the early death of poets. Byron had satirized the melancholy, roaming, lower-class poet Joseph Blacket, the “cobbler poet” who was sponsored by the Milbankes and lived and died in a cottage Annabella’s parents lent him free of charge at Seaham. It was rumored he was in love with Annabella. After his early death in 1810, Annabella wrote:

I left thee Seaham, when the winter’s blast

Had o’er thy summits bare in fury past!

When “Nature’s troubled spirit call’d aloud,” and “admidst the torrents’ rush,” Blacket’s voice was still heard. The dead poet’s nature was “congenial with so rude a scene.” He was “a bard of genius speaking mien,” but “keen suffering quelled” his “native fire.”

The year before, in 1809 in one of her earliest poems, she wrote about the Irish poet Thomas Dermody, who drank “himself to madness and death in 1802,” when Annabella was ten years old:

Degraded genius! O’er the untimely grave

In which the tumults of thy breast were still’d

The rank weeds wave, and every flower that springs

Withers. . . .

So serious a young woman. Caro had nothing to fear from her.

There is no doubt that Byron confided in Annabella, spoke openly of his errant ways with other women. For in her diary she wrote she would continue her acquaintance with the poet “additionally convinced he is sincerely repentant for all the evil he has done, though he has not resolution (without aid) to adopt a new course of conduct and feeling.” In aiding Byron to reach toward his better self—and encouraged by Byron to do so; he probably couldn’t resist leading her along this path—she had become the very good girl determined to save the very bad man. It’s an oath not taken without a burst of virginal eroticism and youthful narcissism. Annabella had no idea she was falling in love.

Her mother did, and didn’t like it one bit. Judith, sharp and protective, had a more sophisticated understanding of the world. Annabella, in the year of the waltz, could write poems about silly women fawning over a poet, but she hadn’t a real idea of the games these people played, even though by then she was with Aunt Melbourne almost every day. Intellectually she might have realized that the most exciting, most titillating game for the ton—outside of reckless gaming—was Love. But she was almost “addicted” to the good in human nature, to the good in herself. Judith was right to fear her daughter was swimming with the sharks.

Because of this concern, and despite her distrust, Judith wrote to her sister-in-law. She told Lady Melbourne in the strictest confidence that she was not at all pleased by this supposedly Platonic relationship between her daughter and the poet. Lady Melbourne responded that she could not disagree with Judith and would keep an eye on the situation and on her niece. Then she turned right around and let Byron read the letter. It was dangerous to show someone as unstable and proud as Byron that he was mistrusted and disliked. It upped the ante in the game of Love.

By the autumn of 1812, the Milbankes had taken up residence in Richmond, a suburb south of London perhaps more economical than Portland Place. Annabella joined them, MM in tow. There, Annabella received a letter from Dr. Fenwick warning that Aunt Melbourne was in many ways “unworthy” of her: “She may in some instances exhibit the Appearance of Sincerity, You Must Not forget that she Can deceive, & has been in the habit of deceiving.” In the next breath he mentioned Byron’s latest poem as if unconsciously linking the Lady’s deviousness to the poet.

Lady Melbourne and Byron had forged a relationship so strong that season of his success that many wondered at the extent of it, though Byron was forty years her junior. The Prince Regent thought it quite peculiar that Lady Melbourne was the confidant of the man who was cuckolding her son, and that she was the confidant of her daughter-in-law as well. William was often away from Melbourne House and had as well a characteristic that his biographer David Cecil would trace from his earliest days up through the time he was Prime Minister of his country. Intellectual, genial William avoided controversy whenever he could. If Caro had adhered to the rules of the game, had kept the golden cord of propriety intact as she saw to her pleasure, things would not have come to a head. But Caro was besotted; some thought her out of her mind when it came to pursuing Byron.

It was not as if she were some teenager without a care in the world. She and William had one surviving child, a boy, Augustus. At the infant’s christening dinner, the erratic playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan made a loud guest appearance, literally crashing the event. He had been the longtime lover of Caro’s mother, and he had an erratic temperament at times veering toward madness–not unlike Caro. Did he think he was the infant’s biological grandfather and had a right to be there? Whoever his grandfather, Augustus was mentally deficient. Caroline and William loved him dearly. He grew big, was destructive, but they refused to send him away.

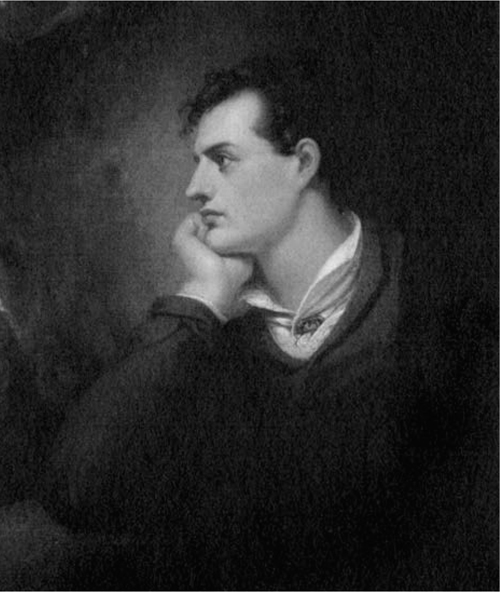

Lord Byron, the young Romantic poet.

For Caro, even beyond this sobering responsibility, it was Byron, Byron, sexual surrender, erotic slavery, love, love. In less than half a year it was all spilling over. Lady Melbourne realized that it might wash away with it her son William’s political prospects. A stop had to be put to the affair. Byron himself didn’t know how to get it to end. Caroline stalked him, forged letters. Finally, toward the end of the year, Lady Melbourne, who often quoted “Life is a tragedy to those who feel and a comedy to those who think,” convinced Caroline to leave England and go to Ireland with William, her child, and her mother, hoping distance would lessen obsession.

All through the year, the correspondence between Lady Melbourne and Byron was full of lighthearted banter. Byron, for all his pride, played the role of the charmed supplicant. But suddenly Lady Melbourne was incensed. Why had Byron promised to write to Caroline now that she had finally been convinced to go to Ireland! Letters would only encourage her! Byron responded, assuring Lady Melbourne his affections lay elsewhere: “I was, am, & shall be I fear attached to another, one to whom I have never said much, but have never lost sight of.” He had wished to marry this other woman, but he heard she was already engaged. “As I have said so much I may as well say all.” Then the Byronic twist: “The woman I mean is Miss Milbanke.”

Her niece?

He knew “little of her, & have not the most distant reason to suppose that I am at all a favorite in that quarter, but I never saw a woman whom I esteemed so much.”

Was he joking? He who fell in and out of love every three months?

“Miss M. I admire because she is a clever woman, an amiable woman & of high blood, for I have still a few Norman & Scotch inherited prejudices on the last score, were I to marry. As to Love, that is done in a week (provided the Lady has a reasonable share) and besides marriage goes on better with esteem & confidence than romance, and she is quite pretty enough to be loved by her husband, without being so glaringly beautiful as to attract too many rivals.”

He had no high opinion of her sex, he informed Lady Melbourne, “but when I do see a woman superior not only to all her own but to most of ours I worship her in proportion as I despise the rest.”

How much of this was written for shock value, how much had the kernel of truth? In her roman à clef, which became a bestseller four years later, Caroline Lamb wrote of Byron in her eponymous novel, Glenarvon: “That in which Glenarvon most prided himself—that in which he most excelled, was the art of dissembling.” He could “turn and twine so near the truth,” with such supreme subtlety, that none could readily detect that he was dissembling. In Byron’s letters to Lady Melbourne he was turning and twining quite near the truth, whatever one intuits of his motives or his sense of play.

“I see nothing but marriage and a speedy one can save me,” he wrote to Lady Melbourne, as Caro was still pursuing him. If her niece was attainable, he’d prefer it; if not, the first woman who looks as if she wouldn’t spit in his face! He had no idea if Annabella would have him: “I wish somebody would say at once that I wish to propose to her.”

That Byron respected Annabella is true. He admired her intellect, her lack of affectation, he enjoyed talking with her and, being extremely competitive, he would have liked to succeed where many of his friends had failed when it came to winning Miss Milbanke’s hand. He saw her as a superior woman. Through her life many an intellectual and artist and grateful supplicant idealized her as such. Caroline herself admired her cousin. And for the moment Byron hoped to run past himself while he still had the chance. Albeit a genius, he wouldn’t be the first man to attempt marriage as a cure. Wealth and position enter into it of course, but that would be true of any women he’d consider marrying—and he insisted he did not care that Sir Ralph was in a bad way financially at the time. Basically, beyond the fun of calling Lady Melbourne aunt, Caro cousin, and being able to spite Annabella’s mother, Byron liked Annabella, was rather taken by her—and her lineage—and, most important, thought she would be safe.

Lady Melbourne actually did intercede, showing her niece selected letters from Byron—possibly reading sections to her as she would have to cull carefully from his other love interests and bawdier remarks. Then, she went further and literally proposed for Byron. He had expected Lady Melbourne to see the lay of the land, not offer Annabella his hand. Looking at it from Lady Melbourne’s point of view, it must have been irresistible to propose for him. It would solve the Caroline problem, annoy her sister-in-law, and keep herself in control.

What apparently surprised Annabella most was not the proposal (she had so many) but finding out that Byron until recently thought she was already engaged. Lady Melbourne knew she wasn’t engaged to George Eden, her childhood friend, as much as he and his family wished it otherwise. (Eden, later Lord Auckland, never did marry.) Why hadn’t her aunt told Byron the truth? Lady Melbourne, as usual, quickly used her head: She “was very sorry for all this,” Annabella wrote, “but not being in my confidence she could not decidedly declare the contrary.” Annabella rejected Byron. To Lady Gosford she shrewdly observed, even without other objections, “his theoretical idea of my perfection” would end in his disappointment.

To her aunt she wrote she’d be unworthy of her dear friend Byron if she didn’t tell the truth without any feminine coyness. She was “predisposed” to believe her aunt’s testimony in favor of Byron’s character. It was “more to the defects of my feelings than of his character that I am not inclined to return his attachment.” She wished Lady Melbourne to forward her letter to Byron, and let him know that she would like to remain his friend if possible. Because of Byron’s pride, Lady Melbourne assumed Byron would cut Annabella out of his life.

Cut her, my dear Lady Melbourne? “Mahomet forbid!” Byron responded, sounding quite relieved. “I am sure we shall be better friends than before & if I am not embarrassed by all this I cannot see for the soul of me why she should.” He called Annabella the “fair Philosopher,” and in another letter to Lady Melbourne called her “my Princess of Parallelograms,” referring to her mathematical talents and to the fact that “we are two parallel lines prolonged to infinity side by side but never to meet.” Tell Annabella that “I am more proud of her rejection than I can ever be of another’s acceptance.”

Refuse Byron? It made what Lady Melbourne considered her niece’s “odd” nature more intriguing and she could not resist asking her to write her, in strict confidence naturally, what exactly were her qualifications for a husband. Serious Annabella sat down in Richmond and composed a list of admirable qualities—duty, respect, good humor, etc. The usual suspects. Lady Melbourne responded by telling her niece she would never marry if she didn’t get off her stilts—or as we’d say, her high horse. And later, of course, when the timing was right, she shared Annabella’s private letter with Byron.

Annabella took her aunt’s rebuke as justified and answered with humor, attempting to show that she wasn’t on stilts. Couldn’t she just be viewed as being on tiptoes (a pleasantly unselfconscious reference not only to her ideals but to her height—just under five feet.) Still, Annabella had refused so many suitors. Had it become a reflex action?

There was one point in Lady Melbourne’s response to her niece’s list of sterling qualities that gives a sharp insight into her own success in the world of men and to her own strength as a mother. It was a rebuke Annabella took to heart, as we shall see. Annabella had confided that her nature was actually a warm one, and her moods often depended on the moods of others. A certain empathy moved her to

be sad when others were sad, happy when they were happy, etc. And she had a temper when provoked.

Lady Melbourne admonished her niece. Allowing herself to be irritated when others were out of sorts required “correction in the highest degree.” With common acquaintances it might be of no consequence, “but if your Husband, should be in ever so absurd a passion, you should not notice it at the time, no Man will bear it with patience.” If she maintains her good humor, when he regains his, he will calm down, listen to her with patience and realize the obligations he has toward his wife. In fact, until Annabella can attain this power over herself she had no right to require it in others. “I have stated this rather strongly, from my persuasion of its importance, & I am sure it is not difficult to acquire, I speak from experience.”

This was Lady Melbourne at her best. It reminds one of the time when the Prince Regent was dining with her and news was brought that his father, mad King George, was failing. Prinny, who had no interest in his insane father’s mortality, wished to continue his meal. It was Lady Melbourne who forcibly persuaded him that he must return to the palace and let the populace see his humanity, his concern for the father he loathed. Though he demurred, she’d have none of it, and called for his carriage. Later that night he came back to thank her for her advice.

On this note let us allow 1812, the year of the waltz, to end and for Annabella and Byron to go their separate ways. Is each age more influenced by its entertainments—or imitative of them—than the other way around? Annabella would accept her aunt’s invitation to the Melbournes’ box at the opera, where as Annabella put it her aunt flirted and singers screeched. Onstage the actors wore their elaborate wigs and swished in their fashionable costumes and cross-dressed, girls turning into pages, pages into girls. The passions were overriding or ironically muted, death and love and marriage and betrayal all took their turn against an artifice of elegance and jewels. Fate hung on a lie, or a misplaced letter, or a false friend. In moments of passion or jealous deception the music swelled. First acts often ended inconclusively, as this one did when the curtain came down on Annabella Milbanke’s first London season on her own. But the tragedy—or the comedy for those who think rather than feel—had hardly begun. For Byron and Annabella, non è finita. No, not finished at all.