12

12

With the death of Augusta Leigh, Ada and her family wore mourning for the aunt and great-aunt who was a stranger in their lives. Ada admitted to Lady Byron that she had been very apprehensive about that meeting at the White Hart, fearing for her mother’s health and peace of mind. “Filial propriety” had prevented her from daring to offer advice. “That filial relation is always hanging like a mill-stone round my neck.”

Lady Byron hadn’t been a millstone the previous decade when Ada returned to her scientific studies after giving birth to her youngest child: “I wished for heirs, certainly never should have desired a child,” Ada wrote memorably to her mother. With that, Lady Byron suggested friend Louisa Mary Barwell to advise Ada in finding the proper help.

“The less I have habitually to do with children the better both for them and me,” Ada wrote to Mrs. Barwell, throwing aside her “customary secrecy.” Scientific pursuits rendered constant attention to children “absolutely intolerable.” Her exceedingly delicate and irritable nervous system, added to this, so “you will not wonder that I begin to feel the children occasionally (to speak plainly but truly) a real nuisance.”

In the Lovelace’s London establishment the children were less annoying, she went on. The town house was so divided that the children could run riot on their side and not be heard on Ada’s. Daughter Anne remembered jumping up and down on beds, doing whatever she pleased, and greedily eyeing her adored older brother Byron’s mutton chops. Lady Byron made the apt observation that she never experienced such unruly children.

Amid unheard chaos, Ada entered into her mathematical speculations with all the intensity and genius of her nature. She shared her mother’s belief that “mathematical science” was not merely “a vast body of abstract and immutable truths,” but “the language through which alone we can adequately express the great facts of the natural world,” so that “the weak mind of man can most effectually read his Creator’s works,” and translate the principles behind them “into explicit practical forms.”

This from the “Notes” Ada appended to her translation into English of Luigi Menabrea’s twenty-four-page article on Charles Babbage’s new conception, his Analytical Engine. These notes were three times as long as the article and established her posthumous fame. She wrote them to defend Babbage’s abandoning the Difference Engine for which the government had already granted him more than 17,000 pounds. Never famous for finishing his projects, Babbage conceived of a more advanced steam-propelled engine. The Analytical Engine would calculate information, not just numbers, Ada wrote in her Notes. “It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. Its province is to assist us in making available what we are already acquainted with.”

She envisioned that “a vast, and a powerful language” would be developed for this Engine. To illustrate, she told Babbage that she wanted “to put something about Bernoulli’s Numbers” into one of her “Notes.” She asked him for “the necessary data and formulae” and with that she wrote a software language for Babbage’s never-to-be actualized Analytical Engine. Her language would have to await the invention of the modern computer. A hundred and twenty-five years after she wrote her “Notes,” a variation of the language Ada created was used by NASA, and named ADA, in honor of the woman regarded as the first computer programmer. Her brilliant foresight added gravitas to what she wrote euphorically to her mother in 1841: “Greatness of the very highest order is never appreciated here, to the fullest extent until after the great man’s (or woman’s) death. My ambition should be rather to be great than to be thought so.”

Her fame has done nothing but grow in the twenty-first century. Students study her in computer classes as they do her father—and at times Ada—in English classes. For along with Ada’s contribution in envisioning the information age, one can now find her as the heroine of much “steam punk” literature. She is presently an icon to the hip.

After her extraordinary “Notes” were published, Ada turned her genius back toward programming games with Babbage. They developed a mysterious “book” that passed between them once a week, most probably a program designed to predict horse-race results. For from the mid-1840s on, Ada gambled—in the compulsive manner of the grandfather she never knew, Mad Jack.

The Countess came to racing with a mathematical program, a childlike sense of her infallibility, and a focus that reminds one of when she was twelve and obsessed with flight. She was well aware of her mother’s belief that moral traits could be inherited. Lady Byron became a millstone around Ada’s neck as Ada attempted to keep the extent of her gaming from her mother, all the while requesting more and more money from her, ostensibly for fine books and Court dresses. At the same time, Ada being Ada, she bubbled over with racing news in her letters to her mother. On Lady Byron’s fifty-eighth birthday, May 17, 1850, Ada wrote: “I am afraid you will take no interest in what interests me much just now,—viz: the winner of the Derby.” That race was two weeks away and Ada was “in danger of becoming quite a sporting character.”

Ada and Lovelace were guests of the aristocratic owners of the great horses of the day and went from country home to country home during racing season. As a result, they were often in proximity to Newstead Abbey, the medieval estate that her father had been forced to sell. In 1850, in the gap between meets, Ada visited Newstead Abbey for the first time. It had been bought and was kept up by Colonel Thomas Wildman. For two days she wandered around the Abbey and the grounds without uttering a word to anyone, seeing nothing but death all around her. Newstead was like falling into a grave, she wrote to her mother. Her depression may have been heightened by the menstrual hemorrhage she had recently suffered, similar to the one she had had a few years previously while visiting friend Charles Dickens.

Yet, after this initial gloom, her spirits lifted and she became as enamored of the Abbey as she had previously been appalled. It is often said that Ada may have been bipolar. If she were, these terrible menstrual cycles, her Black Dwarf, contributed. Suddenly she was overjoyed: The tapestries, the skull’s heads young Byron and his friends used to drink out of in nights of revelry, the ornate furniture, the medieval flavor of the estate—it was all kept as it once was. She went to the nearby church where Byron was entombed in the crowded vault with his ancestors and afterward wrote to her mother playfully: “I have had a resurrection. I do love the venerable old place and all my wicked forefathers.”

Lady Byron, who was working with Robertson on the Memoir was appalled: For all Ada’s secrecy, Lady Byron knew her daughter was lately living among “partizans” of Byron who “consider me as having taken a hostile position towards him. You must not be infected with an error resulting from their ignorance, and his mystification. I was his best friend, not only in feeling, but in fact.” In her mind, Lady Byron considered she was writing about her marriage for her grandchildren, but Ada had no idea of what she meant when she wrote: “It often occurs to me that my attempts to influence your children favorably in their early years will be frustrated and turned to mischief,—so that it would be better for them not to have known me,—if they are allowed to adopt the unfounded popular notion of my having abandoned my husband from want of devotedness and entire sympathy—or if they suppose me to have been under the influence at any time, of cold, calculating and unforgiving feelings,—such having been his published description of me, whilst he wrote to me privately, (as will hereafter appear) ‘I did—no do—and ever shall love you’—”

Ada was so astonished by her mother’s outburst that she felt “some difficulty in replying.” Her mother’s letter seemed “addressed to a Phantom of something that don’t exist.—No feeling or opinion respecting my father’s moral character, or your relations toward him, could be altered by my visit to Newstead, or by any tone assumed by any parties whatever.” As far as her “having a mythical veneration for my father, I cannot, (to adhere only to personal considerations) forget his conduct as regards to my own self, a conduct unjust and vindictive.” A rift developed but was eventually resolved. Lady Byron made amends through her beloved son-in-law. Ada had told her of a prophecy that Newstead would one day return to the family. Should Lady Byron buy the estate for her daughter? She sent Lovelace to inspect Newstead and advise her as to its financial feasibility. It did not get as far as asking Colonel Wildman if he would sell, for as the Crow reported to his Hen, after careful inspection, Newstead was not a good investment.

Meanwhile, Ada kept gambling. On the recommendation of Babbage, she hired Mary Wilson, Babbage’s deceased mother’s lady’s maid, as well as her husband. Each week as Babbage and Ada sent their mysterious “book” back and forth, Mary placed bets with the bookies, something a Countess did not do for herself. Protected as she had always been from the world below her station, Ada also trusted her lover—perhaps latest lover if the rumors were accurate—John Crosse.

John was a good-looking dark-haired man with a mysteriously marked jaw. Six years older than Ada, he was the eldest son of Andrew Crosse, a well-known amateur scientist whose eccentric experiments in electricity and electrocrystallization made him a prototype, people said, for Mary Shelley’s Doctor Frankenstein. Ada met John while visiting his father’s home laboratory. In these years before John inherited from his uncle Hamilton, took his name, and became the gentleman he pretended to be, John Crosse was a confidence man. It was he who brought Ada into a demiworld of gamblers and extortioners, and it was they who convinced her that her mother would never understand her gambling any more than she understood Lord Byron.

The one of them called only “Fleming” was most likely the Wilmington Fleming who had once attempted to blackmail Augusta Leigh with his copies of Caroline Lamb’s explicit journals concerning Augusta and Byron’s love affair. Caroline had foolishly let him borrow her journals while they were “good friends.” Augusta had appealed to Lady Byron, who wrote to her cousin William Lamb about Fleming’s demands. The future Lord Melbourne refused to be blackmailed over his wife’s journals, and Lady Byron sought legal advice which she passed on to Augusta: No one in the family, particularly Augusta, should take any notice of Fleming’s threats. Let him rave on if that was what he wished to do with his supposed “copies.” To this, Augusta answered regretting that she had such unhelpful relatives and, against advice, had John Hanson go to Fleming. Lady Anne Wilmot-Horton would later wonder if Augusta had been blackmailed through her life, as she could find no other reason why a woman of her means—Augusta did, at first, have access to around 3,000 pounds per annum—was constantly in debt. Ada had no idea about any of this past history, shielded as she was from the underclass. It was no wonder that John Crosse, Fleming, and a bookie referred to as Malcolm wished to separate Ada from her mother, who knew much more about extortion—and specific extortionists—than did Ada. They impressed upon her that she, after all, was Lord Byron’s daughter. They also told her all of her mother’s friends hated her “like poison.”

Except for one friend of her mother. Ada confided her gambling losses to Anna Jameson, swearing her to secrecy about that and about John Crosse. Hardworking Anna, who had a loan from Lady Byron, and who hardly made ends meet, lent a countess money and did keep Ada’s floundering finances a secret from Lady Byron. Ada confided as well in her and her mother’s mutual friend Woronzow Greig, sending him to Lady Byron to ask for an increase in Ada’s allowance. Greig was the son, by her first marriage, of the famous woman scientist Mary Somerville, another friend of the family. Lady Byron trusted this amicable lawyer and amateur scientist. Greig was to impress on Lady Byron that Ada was in arrears because of the necessities of her station and her intellectual interests. “This is the whole my mother knows, she must not know more.” If Lady Byron knew of “the debt,” it would do immeasurable harm “in more ways than one.”

Lovelace was doing a bit of gambling himself at the fashionable meets, but seemed to have no idea of what Ada was betting weekly. His passion was architecture, applied to constantly improving his properties, adding turrets and turns and even having a “Philosopher’s Walk” for Charles Babbage at East Horsley, his estate, near Ockham in Surrey. At his summer residence at Ashley Combe, Lovelace did some superb landscaping. Though Ada suffered from increasingly horrific periods and hemorrhages, Lovelace never found enough money to make her a bathroom at any of his properties, even on the first floor as she requested. Nor did his interest extend to installing up-to-date water closets. He was an easy mark when it came to his wife’s comings and goings, not when it came to advancing her money.

The Lovelaces’ finances were indeed dwindling. The year after Lady Byron gave Ada the “hundreds” that she herself went and asked for, Ada and William moved from St. James’s Square to a town house at 6 Great Cumberland Place. It needed many repairs and Lovelace took a loan from the Hen for 4,500 pounds secured by his life insurance policy. Money problems increased. In August after the Derby, Ada wrote to her fourteen-year-old animal-loving daughter that they were going to have to reduce their “family of dogs” at the Ockham estates. “They cost too much.” Also “we must keep a horse or two less.” Ostensibly, debts were attributed to William’s passion for architectural improvements. He did win a prize the next year at the Great Exhibition of 1851 for improved brickmaking.

On her mother’s fifty-ninth birthday, Ada wrote to Lady Byron under the heading “(Doomsday).” In it, Ada’s peculiar mixture of naïve openness and deliberate fabrication appeared manic, like a back slapper who had too much to drink. She wished her mother would live as long as possible and that she herself would be “as old some day as you are.” “Voltigeur’s defeat distresses me less than your age.” It was obvious she had staked her aristocratic friend’s great horse, for she suggested another visit to her mother in that letter. A few days later, at the Epsom Derby a long shot came in and Ada lost 3,200 pounds. Mrs. Jameson wrote to Ottilie von Goethe that she heard the Countess of Lovelace had lost a fortune; she hoped it wasn’t true.

It was. Ada was in debt with bookmakers, tipsters, merchants; she hadn’t even paid the ten pounds or so outstanding to the chaperone on daughter Anne’s first European trip. Her lover John Crosse had a partial solution. He convinced her to let him have paste replicas made of the Lovelace family jewels for a hundred pounds, and then he secretly pawned the Lovelace diamonds without Lord Lovelace knowing a thing. Paste and pawn came from a different world, one which now had its claws into Ada, and needed to be paid off. Dunned by bookmakers and, according to biographer Doris Langley Moore, also being blackmailed, an ill and depressed Ada was forced to enlighten her husband. Lovelace was stunned by the enormity of Ada’s debts.

IT IS IMPOSSIBLE to impress upon the reader the extent of Lovelace’s loving relationship with Lady Byron up until the middle of June 1851. This was the man Lady Byron told her daughter was “the comfort of my life.” Lovelace’s steadying arms had relieved Lady Byron of being the sole protector, the single mother, of an impressionable daughter. And as for Lovelace, he had never before experienced such motherly devotion. The Crow, however, was not an introspective man. Nor, would it seem, did he know much about women. On one hand, he frugally refused Ada a bathroom; on the other, there was John Crosse right under his nose having an affair with Ada and accepting expensive gifts. One shouldn’t be derided for having faith in one’s wife—or believing in the unconditional love of one’s mother-in-law—but there you have it.

In the middle of June 1851, a despairing Lovelace arrived at Leamington, where his mother-in-law was resting. Lady Byron had just come from her estates at Kirkby with an aching face—a common problem in those days of primitive dentistry. She was taking a stop on her way to London, where dear Selina Doyle lay dying. Lovelace burst into his mother-in-law’s quarters at eleven o’clock at night, intruding on the privacy, at times the isolation, so necessary to Lady Byron’s stability. In panic, reaching out son to mother, he gave Lady Byron the shocking news of her daughter’s enormous gambling debts.

“Genius is always a child!” Lady Byron cried out. Lovelace had allowed impressionable Ada to be exposed to low and unprincipled associates, the very people he should have protected her from. He sent her to the Doncaster meet alone? The moment he consented to Ada attending without him, he had deserted his wife! He knew what “overweening confidence” Ada had in her abilities. He was her husband, he had to be firm, not afraid of her violent eruptions! Ada’s temper tantrums passed away and never did lasting harm. He knew that! Why hadn’t Ada told her the truth last spring? Lady Byron moaned. “She might have had as many thousands as I gave her hundreds.”

For fifteen years Lady Bryon believed her exceptional daughter had finally found the “protection” of a father’s arms. That night at Leamington, she withdrew to her bedroom. When Lovelace asked to see her the next morning, she refused. Her affection for Lovelace, though strong, had been the conditional love of a mother who believed she had found a safe and fatherly haven for her Byronic genius of a daughter.

She wrote to Mrs. Jameson a few days later expressing her distress without revealing its cause, having no idea Jameson knew all about Ada’s gaming and hadn’t alerted her. She told her friend she had left her estates at Kirkby for Leamington on a rainy day, supposing she was “done with acting Queen upon a ludicrously small scale.” However, on the road through the village, though the rain continued, “I was to pass lines (like Washerwomen’s lines)” of suspended flowers.

“At last my carriage was stopped by a crowd of Women. They had assembled to offer me a hugh Garland, with a paper pinned to it expressive of their wish that I ‘should live long and die happy.’—I got out of the Carriage to take the Garland, and demonstrate my gratification. Some of the elder school girls had come up to show me how well they had worked the Prodigal Son and Mount Vesuvius! You should have been there to admire.” In her new bitterness, she made light of the gratitude of the girls for whom she had set up a school and of the women whom she had supported during the weavers’ strike. Looking back at that scene, she told Jameson obliquely, “It seems to me now like a play—other and deeper interests even than those I have told you, have made the scenes unreal—so much loved by strangers—so little by the nearest!”

Selina Doyle died before her old friend could reach London, so Lady Byron returned to Brighton and sought out Robertson. Then she did something reminiscent of the dark days after her separation from Byron. She hired a small boat and “cradled” herself on the “rough” roll of waves. Once more she emptied her stomach into the foaming sea. “My whole frame seemed to be liberated.”

Lovelace was stunned by the Hen’s anger. Family friend Greig attempted to mediate. Using the approach that he and Dr. Lushington and other intimates knew worked best on the dowager Lady Byron, he first confessed his own error to Lady Byron—that of not considering her attitude toward Lovelace justified. He hoped she would forgive him. When he recently learned that Lovelace gave Ada an open-ended letter of credit to bring with her to the Doncaster races, he understood Lady Byron’s position entirely. Lovelace was in the wrong to have done such a thing. “Remember that he never had a Mother, and let your heart pity while your judgement condemns him. He has lived a solitary and an isolated life, so far as parental ties and habits are concerned. I admit that he is to be blamed, but I think he is also to be pitied as . . . he wishes to act right.”

The only problem with genial Greig’s psychologically apt attempt to mediate with a woman who had an overriding faith in her own judgment was that Lady Byron had not known that Lovelace gave her daughter—this childlike genius with no sense of her own limitations—a limitless letter of credit! She only knew he had allowed her to go off to the races without his protection. Lady Byron became more convinced than ever that she was only loved by strangers stringing up paper flowers on rainy days.

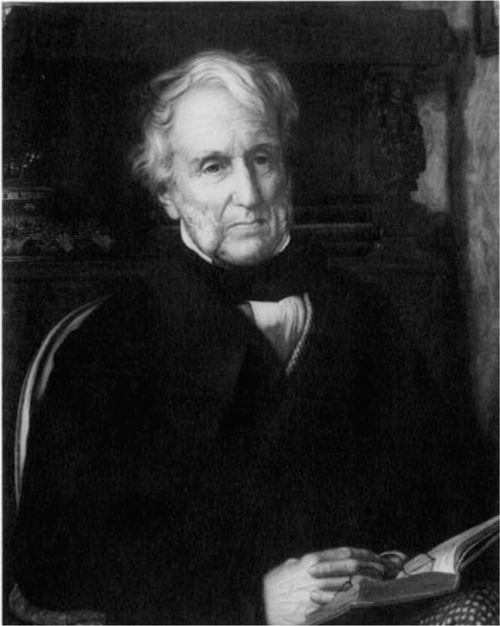

The elderly Lushington, who attempted to reunite Lady Byron and her daughter.

Ada was outraged at her mother’s treatment of Lovelace and took her husband’s side. It also gave her a good excuse for not facing her mother after so many of her lies were exposed. That her daughter would not see her did not stop Lady Byron from settling Ada’s debts. She sent Dr. Lushington to procure a complete list of what was owed. By that March 1851, Dr. Lushington was close to seventy, still as active as he was distinguished. As he traveled to Ada, Lushington remembered he had been the girl’s champion almost since her birth. Arriving at 6 Cumberland Place, he was shocked. In the months since he had last seen the thirty-five-year-old, she had turned into an emaciated invalid who had to be rolled out into the London air in what he described to Lady Byron as a bath chair with rubber wheels. When Lovelace had burst in on Lady Byron at Leamington, he brought along a worrisome doctor’s report as well. Lady Byron had been so distraught that she seemed unimpressed by it. She may have thought he brought it to placate her. Ada always had bad periods. Her health was constantly up and down.

However, Ada was in decline. Her Black Dwarf was uterine cancer. As doctors gave hopeful and erroneous prognoses, it was already spreading into her intestinal tract. Not that anything could have saved her, but she was heading toward excruciating pain. There is a portrait of Ada at her piano at this time. One could easily mistake the woman in her mid-thirties for a frail innocent child of twelve. In a way, she was. As Ada’s physical condition worsened, her gambling cohorts pointed their shark’s teeth at her, and a frightened Ada agreed finally to see her mother.

“SUCH A DAY,” Lady Byron wrote to Robertson of the reunion with her daughter in London that spring of 1852. “I believe I am now in possession of all that has been so studiously kept from me.” She told Robertson these revelations did not come “from spontaneous confidence.” They came from Ada’s “fine capacity for arriving at a Truth”—through inductive reasoning. Ada had reached “the conclusion (in her own words) that the wisest course for her is to consider me as her best friend—that she should do so at this moment may save her life, and be of the greatest consequence in other ways—”

The “other ways” in which Lady Byron could save her daughter’s life were daunting. For a short time in June, Lady Byron took Ada off pain medications, for which her later detractors demonized her, suggesting Ada was allowed to suffer through the course of her illness for the good of her soul. In fact, Ada was given opiates, belladonna; cannabis was discussed as a possibility; and finally it arrived—the water bed. In that unmedicated period Ada was able to unburden her conscience to her mother. It was then that she told her that she had given her lover John Crosse the Lovelace family diamonds to pawn and substituted paste. Ada hadn’t dared include this on Dr. Lushington’s list of her debts. What was going to happen when her husband found out? Lady Byron acted immediately. She sent Dr. Lushington with the 800 pounds plus interest to reclaim the diamonds from the pawnbroker, and gave them back to her relieved and suffering daughter.

Ada in the last year of her life.

Ada was in constant pain for all the cheerful prognoses she was offered. Her sickroom was moved to the drawing room floor, where she could be closer to whatever activity of life she could perform, at the same time as she was more easily attended to by her round-the-clock nurses and her chief physician, Dr. West. She was able to get to her piano occasionally, took meals at table at times, wrote a plethora of notes in these months, all in pencil. Pencil was a sign of decline. The person could no longer control inkpot and pen, and was usually writing in bed. Lady Byron lodged in London that summer to be with her daughter every day; Lovelace split time between Ockham and London.

When Ada could not get to her piano, daughter Anne played for her—not as well, but that no longer mattered. How could she have ever wished not to have a daughter? Ada asked her mother more than once. Anne came up to her grandmother one day after Lady Byron left the sickroom and asked, “Whatever will Daddy do?”

“Not another word would she utter. I burst into tears.”

RECONCILED WITH ADA, her mother wrote to Robertson that Ada told her she could no longer go “24 hours” without prayer. Lady Byron hoped for a cure. The pain was such that Ada could not stay still. Her “strange contortions” were a cruel mirror image of her fidgeting childhood. Lady Byron heard of a successful cure of a case like Ada’s by mesmerism. “I only want to mesmerize her once.” Which she did in July, after dubious Ada agreed to it. The mesmerist stilled her for a short time, leaving her with a flushed face and hot hands. The experiment was not repeated.

What had the power to calm Ada was this renewed contact with her mother. When one reads in Lady Byron’s unpublished papers of the two of them together, it is almost as if the past were rekindled—perhaps “redeemed” is a better word—and the child in Ada no longer had to search for her mother through the flight of birds and the invention of steam-run machines. When finally diagnosed properly, Ada told her mother, the thing she most dreaded was “the idea of your being far away.” That same day, the actor Mrs. Sartoris, Lady Byron’s friend, came and sang Handel. That evening, as her mother left the room, Ada said “the worst of dying was that ‘it must be done alone.’ ”

By the middle of July, Lady Byron decided “to write a journal” and to make her friend Emily Fitzhugh, a minister’s daughter, “the keeper of it.” She wished “to write it like a disembodied spirit,” setting down “pure fact,” not personal feeling. This disembodied persona served her better in Ada’s sickroom than it did when speaking with Robertson about her life with Byron. For she was now caregiver in the service of her daughter, her one object “to make myself the medium of Christian influences, everlasting cheering.”

Twentieth-century critics of Lady Byron emphasize “Christian influences” as if mother spent her time sermonizing a dying daughter. Far from it. Ada wished to make her peace with her maker before she died, a common desire in the nineteenth century, and in doing so her mother was a help. However, neither was doctrinaire. Ada was a Unitarian, and Christianity to Lady Byron was following he who did good. Lady Byron’s “everlasting cheering” did reflect Ada’s hope of redemption. But it also meant that Lady Byron as mother rose beyond her own grief. When Ada’s eyes opened, she had the comfort of her mother’s loving face. When she spoke, she had the comfort of an honest response. In the unpublished journal one realizes the ongoing conversation between mother and daughter was the bridge that healed the rift between them and brought Ada peace. “I don’t see my way out of this,” Ada said, and felt “regrets” at not having done more while she lived.

“I pointed out few thinking minds ever felt their ends accomplished yet the survivors had been influenced by those lives in an unforeseen manner leading us to believe that the ends of our existence were hidden from us.”

Ada said, “I suppose the process of dying is not so painful as some things we suffer in life.” She told her mother it was very curious that “she had never felt discontented for a moment—that the constant nausea was the most difficult to contend against.”

During the last week of July, Lovelace had been at East Horsley with friend Greig. They were speaking of Ada and her illness and of Lady Byron’s coldness to her son-in-law when they were caught in a sudden summer shower. They ducked into a nearby shed to wait it out. As they continued their conversation there, Greig happened to mention John Crosse’s wife and children. Whatever did he mean, Lovelace asked in astonishment. John Crosse was a bachelor.

“Is it possible that you do not know Mr. Crosse is married?”

Lovelace, unaware that Crosse was Ada’s lover, would not believe his friend had purposely misrepresented himself. He called Crosse on it and within a few days received one conflicting story after another, which Lovelace tried to believe, at the same time sending each of these rather loony fabrications on for Greig’s legal opinion. John Crosse, on his part, was tipped off by Lovelace’s questioning him. He got to 6 Cumberland Place as fast as he could in the first days of August. Maid Mary Wilson made sure he could visit while Lady Byron was not present. Crosse once more left with the Lovelace diamonds to pawn. This time he obtained Lovelace’s letter of open credit to Ada, as well, one that could be used against Lovelace in court. Later that month the shadowy “Fleming” found his way to Ada while she was alone. Not only did he gain access unobserved, but he brought a lawyer with him and Ada signed a life insurance policy and deed of appointment over to him at a time when it was obvious she could hardly hold a pencil.

Ada told her mother that through her life she would always “try experiments” but their outcome carried no weight with her. She would try again. Was Ada aware that she had once more “experimented” by giving Crosse the family jewels for a second time? She may have had a shadowy recollection, but soon it was erased. In the middle of August at two in the morning, Ada’s screams woke up the household. Lady Byron was called from her lodgings. Lovelace was already by Ada’s bedside when Lady Byron arrived and together they witnessed “Indescribable pain.” On all fours, the only position that offered the slightest relief, Ada howled. Then after a series of epileptic seizures, Ada fell into a sort of coma. Lady Byron went over and touched Lovelace’s arm “kindly” when she passed. “(Could not help it),” she wrote, “but no notice was taken.”

Could God’s love be proved? Ada asked her mother when she returned to her senses a few days later.

“Can you prove what I feel towards you, Ada? Yet can you disbelieve it?”

In the last week of August, Lady Byron moved in to what she called “Lord Lovelace’s house” to be “in constant attendance upon Ada.” She was put in charge of 6 Cumberland Place by her son-in-law’s request. “I am not fond of power,” Lady Byron wrote, “but I must submit to rule.” She meant it. When a college for women was being founded a few years previously, she was willing “to be on the committee of the New College,” but she refused to be a “Patroness” when asked: “I want to give advice without authority to enforce it.” Her advice: Maria Edgeworth should be “first in the list of Patronesses” and “Miss Segewick should represent Educational America.”

The day before Lady Byron moved in, on August 21, Charles Dickens came to visit. Though many artists had come, particularly to sing for her, Ada herself had asked for Dickens. He “amused” her, Lady Byron wrote. Dickens was a world-famous reader of his work; audiences thronged to hear him. His entrance caused a stir among the staff. One imagines the downstairs servants coming far enough upstairs and those maids above leaving their chores and peering down into the drawing room where Ada laid tended by her nurses. Dr. West was there, as well as the visitors who dropped by to inquire. Lady Byron and granddaughter Anne were in attendance. Ada had requested her friend read the death scene from Dombey and Son. Dickens’s voice rang out through 6 Great Cumberland Place and there were plenty of tears when he ended with: “Now the boat was out at sea, but gliding smoothly on. And now there was a shore before him. The golden ripple on the wall came back again, and nothing else stirred in the room. The old old fashion! The fashion that came in with our first garments, and will last unchanged until our race has run its course, and the wide firmament is rolled up like a scroll. The old, old fashion—Death!”

If death had any art to it at all, Dickens’s reading would have brought down Ada’s curtain. She seemed prepared. She wished her husband “every earthly happiness.” She begged her mother not to let her be buried alive. (That happened a lot in France.) Daughter Anne and son Byron, on leave from his ship, were allowed to sponge Ada’s hands and face. It reminded her of rippling waters and she smiled. Her children did too. The next day, when Lady Byron moved in to be with Ada “day and night,” Lord Lovelace took son Byron with him to Ockham to repair after that horrendous scene of his mother’s seizures.

It had been Lovelace who insisted—actually forced—son Byron to go to sea at the age of thirteen, against the boy’s objections. The father wanted to make a man of him, and had been severe in his treatment of his firstborn since Byron’s earliest years, ridiculing his sensitivities. When the Seventh Lord Byron thought of sending his son to sea at an early age, Lady Byron would write to him of the damage it had done to her grandson.

“Can nothing save me?” Ada asked her mother after her husband and Byron left.

“Nothing,” Lady Byron replied, but there might still be ways for easing her suffering. Cheerfulness did not mean duplicity.

Ada told her mother that she had many regrets concerning her. “I have been thinking what a strange fate yours has been.”

“I replied, ‘So would the fate of most people appear if all were known.’ ”

So was Ada’s: “I had been thinking how she might have some pleasing feeling associated with that last resting place,” Lady Byron wrote in her journal letter, for Ada had told her she didn’t want to be buried at Ockham. “I determined to propose Newstead.” If this caused people to gossip, what could the opinions of the world “be to me?” She told her daughter she had an alternative to the Lovelace family vault to suggest.

Ada looked at her eagerly: “Well?”

“Newstead,” I replied.

“Her face lighted up with pleasure and relief and she said ‘We have settled it. I have written to Colonel Wildman about the spot situated by my Father.’ ” She hadn’t told her mother because “I thought you would be angry with me.”

“I dispelled that apprehension entirely.” However: “I was secretly wounded by the reserve. My journal is not however to be feelings of my own—away with them.”

Even in their new intimacy, Lady Byron was still Lady Byron, shooing away her feelings. Ada was still Ada, keeping a secret about wanting to be with her father that might displease her mother. When with her husband, she did not wish to displease him either. “Within a week of her seizure in August,” Lovelace wrote to Lady Byron, “Ada told me that before her hour came she should speak strongly to you about your injustice to me.” Ada never spoke up for her husband. She had long since lost whatever affection she once had for him. Instead, her guilty conscience was such that awakening from the seizure to find her mother and husband with her, she told them that after death she was sure she would have “a million years” of the pain she was suffering.

“Her terror and distress were great. At last she turned to me earnestly: ‘May I ask God to forgive me from you?’

“My answer freed her from all fear. ‘Have I lived in vain?’ ”

Then Ada turned to Lovelace: “ ‘Will you forgive me?—’ ”

“This is the best moment she has had and for that she must have been kept alive,” Lady Byron wrote.

Later that day, that “best moment” turned to fright. Ada saw the ghost of Lord Byron. Lady Byron’s usually clear handwriting mirrored mounting stress. Ada had mistaken a dream for reality: “That her father had sent her this disease and doomed her to an early death!” Disturbed as Ada was, her mother finally made her laugh. Her handwriting deteriorating, Lady Byron then wrote: “She says she hopes to live. I said, ‘You are dying—you may not have another day—use this well.’ ”

Ada would have three more months.

“Have I lived to hear it?” Lady Byron wrote in September. “—She has just said ‘There is but one reason why I could wish for life—to live with you entirely.’ ” With her mother’s protection she might have lived “happily for herself and others.” Lady Byron kept “saying to myself ‘Wonderful God! There is something sublime in the redeemed heart. I have the feeling of looking up to it.’ ” The redeemed heart had hard truths to reveal to her husband, though she did not tell him about the pawning of the diamonds. Instead, in her penciled scrawl Ada “confided all my letters, property and affairs to my mother and informed her of all that had passed respective of the family jewels.” Before Lord Lovelace went into Ada’s room that third week of September, to listen to Ada’s confession about her affair with John Crosse, Lady Byron demanded that “he must hear what she might wish to say, but reply as little as possible and as calmly.” Instead, “I saw his angry countenance after he left her,” and “he was unwilling to speak of the Interview to me, as he usually does. I inquired—he said ‘It was very painful.’ ” Lovelace had found it “impossible not to contradict” Ada, though before he left his wife he did say, “ ‘God be merciful to you!’ ”

“God be merciful to him! Pharisee as he is, from whom his poor penitent wife could draw no kinder expression by her complete submission and humbling. For such was her spirit—I knew.”

Right after that painful interview, Lovelace put in writing that when he was out of London, “it is my wish that Lady Byron should be considered in every respect as mistress of my home and family and to possess all the authority of Lady Lovelace and myself.” He also agreed with Ada and made Lady Byron guardian of the two younger children, Anne and Ralph, who had recently arrived. He must have expected, after Ada’s confession, to be away from home more often.

Lovelace later complained to Lady Byron: “That I should forgive Ada the wrong she confessed appeared to you so simple as to elicit from you neither surprise nor approbation. And you who remain unforgiving to the end accuse me of rigidity!” Of course, what the poor man would never understand was that Lady Byron in those months had become every inch a mother—only not his. No longer was she the “Hen,” she was the Lioness protecting her cub.

At the end of September, in one of her penciled notes, Ada confirmed that she wished to be buried “by my Father’s side” with a “simple little marble monument,” with a quote from St. James. She double-underscored “If he hath committed sins, they shall be forgiven him.” She took a “fancy” for her mother’s black muslin shawl to be wrapped around her shoulders. “All causes of mental disturbances have been averted and if the mind turns to the past, it is only for the relief of speaking to me.” Ada “liked to be told little pleasing things.” Lady Byron “made her smile, almost laugh, by saying to her (having read a bequest of hers to the neighboring Poor in the County) ‘You mean to make the poor people rejoice in your death’—but I added ‘it will be a tearful joy.’ ”

In a jagged, pain-ridden handwriting Lady Byron told her journal, “My fog thickens and my throat and chest too.” She looked at her daughter as she wrote. “I see more deadly paleness and some drop of the jaw yet it is not yet the seal of Death.” On October 1: “Yesterday evening I sat by her bed in Twilight, silently—then I said, ‘I feel what I must call happiness—so calm and thankful!’ ” Ada answered, “ ‘And I share it in a degree—at least I am not unhappy—only sometimes when in great pain.’ ”

A spent Lady Byron took her granddaughter to Westminster Abbey the following Sunday. The day before, young Anne had experienced her mother losing sight and hearing. She told her grandmother going to Westminster “ ‘did her good.’ ” Music raised her above the painful things and “ ‘made life appear only a dream and the reality beyond it.’ ” Always devoted to granddaughter Anne, Lady Byron wrote, “I had gone for her sake—for rest alone would have been better for me.”

When her sight and hearing returned two days later, Ada pointed out to her mother a “ ‘man all light, sitting at the foot of her bed and calling her to come with him.’ ” She was sure that “I must see him also.” Since her attack in mid-August when her howls ripped through the house, Ada’s memory of preceding events had fogged. Suddenly tranquility was shattered. In looking over her papers in October, Ada remembered. She had handed John Crosse the Lovelace diamonds a second time! Her panic was so severe that her mother thought it might kill her. Lady Byron tried to calm her, reassured Ada she would take care of everything. Which she did, retrieving the diamonds for under 900 pounds. This time Lady Byron kept the jewels and the paste replicas in her possession until she was able to deposit them at Drummonds. Lovelace still didn’t know.

Ada expressed “bitterest regret that she had not earlier trusted me—that she could not.” Lady Byron comforted her daughter, saying that all of us had at times trusted “shadows.”

“The shadows are gone, are they not?” Ada asked fearfully. Her mother assured her “they would never again return.”

Mary Wilson and her husband, who had facilitated her private meetings with her lover Crosse and with Fleming, had come to Ada through Babbage, whom Lady Byron respected. Lady Byron dismissed them in October, to Babbage’s anger and to the dismay of later critics who saw it as another example of Lady Byron’s implacability. Why wouldn’t she dismiss them? They had colluded with John Crosse, yet Lady Byron did not yet know half of it—that the blackmailer Fleming had been allowed entrance with a lawyer at a time when Ada was hardly in her right mind. However, Ada begged her mother that “no consequences painful to them should be inflicted, unless absolutely necessary.” So Lady Byron later paid the Wilsons the 100 pounds Ada had bequeathed each, sending with the money a letter clearly stating she had no use for them and that she honored the bequest only because she obeyed all her daughter’s final wishes.

“The less serious topics” spoken of in October have been “amusing anecdotes of the Children, simple plans for the Poor, using her—power to put things in order (order now a word of hers).” Ada also expressed a “passionate” desire to see natural beauty, and was given prints of mountains, flowers, birds with bright plumage. Illness had also turned Ada less self-involved. She was quite aware she was comforted by competent doctors and an entire nursing staff. She wanted to leave something to help the poor who were ill. Though Lady Byron always preferred Florence Nightingale’s older sister, when she conferred with Florence concerning Ada’s bequest, she admired Nightingale’s way of entering into the plan with her strong mind and managerial skills.

When Emily Fitzhugh blamed Ada for becoming “alienated” from her mother, Lady Byron would not have it. Once more she protected her cub. Emily must “remember the ‘conspiracy’ the uniform image of me that was reflected from all sides—the terrible, stern, unrelenting Lady B.” With Ada having a guilty conscience, how “could she have sought such a Parent?” Alienation was not her daughter’s fault, but the result of the “black treachery” of false friends. “She was a mere child—and became a slave.” She told her mother, “There never was such a conspiracy as that against you on all sides.” There had been a concerted attempt “to enrage her towards me—and prevent any renewal of intercourse.” Who could love such a woman? Lady Byron told her friend to reread the ending stanzas of The Third Canto of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage to underscore the world’s negative conception.

“She has mentioned as one of the causes of her loss of moral perceptions the Idolatry in which she was encouraged by all around her.” They praised Lord Byron saying he was as good a man as he was a poet, and a “halo” was thrown around his aberrations. “Gradually I was then placed in an unfavorable light . . . as if I could not enter into the Byron nature and could sympathize as little with the Daughter as the Father—yet she says she never ceased when with me to feel differently, and to be drawn towards me—and therefore she kept out of the way of being influenced by me.” Now however, “the voice of Nature and the Will of God together have given me my Child again.” She corrected herself. “No not again—for she never was mine.”

Ada’s children surrounded her. Ralph, the youngest and meekest, knit cuffs for her, Anne, the middle child, played piano for her, Byron nursed her. When Byron was summoned back to his ship, Lady Byron was advised not to allow Ada a parting. “She would die they say under the emotion. I must take it on myself to deprive him of that Farewell.”

On October 21 at seven in the evening, she watched her teenaged grandson look “through the half opened door at his Mother’s wasted form and hands—her face he could not see—she was awake—but unconscious of that last look—more affecting to me than what was ever more effecting.”

Soon after, Ada called for her mother “to talk cheerfully to her.” When Lady Byron told her daughter Byron was gone “she said she could not have borne to know he was going.”

“Poor Anne came to me for consolation last night.” Her granddaughter told her “she never hopes anything here, only ‘beyond,’ ” but “drawing is her great comfort.” (Lady Byron hired John Ruskin as Anne’s drawing master.)

“ ‘O what a good bargain my Illness has been,’ ” Ada exclaimed at the end of October. However, a few weeks later Ada’s “renewed agonies have been mitigated by Bella Donna but Dr West says we must not expect it to be effective long. I am no comfort to her now.”

Ada had warned Lady Byron in August that her mother’s good influence would be wasted on Byron, just as it had been wasted on her when she was young: “He has so many of my faults.” It takes a Byron to catch a Byron, she quipped. However, his grandmother had witnessed Byron “gliding” around his mother’s room with the “gentleness of an experienced Nurse.” “I see his character—as fixed principle to do what is Right.” In November, Lady Byron only had “time for facts.” Byron had jumped ship and a warrant had been issued for him. He made two attempts to get hired as a common sailor on an American ship and “had been living and sleeping and drinking with the common sailors.” Byron, the titled Lord Ockham, called himself Johnny Okey and escaped the police by living quietly. “I believe I will withdraw now from the position of advisor,” Lady Byron wrote.

“ ‘Speak to me,’ ” Ada whispered a few days later, breaking a long silence. “I spoke of the persons I had seen today and of their feelings toward her—”

“ ‘It seems to me interminable—I may get a little strength again to look at a book or write.’ ” Just saying that exhausted Ada until “some support was administered—Then she said that her great distress was the inability to utter her thoughts, that she was always thinking when awake.”

It was “the last time she has spoken to me.” In the stillness, Lady Byron sketched Ada, who was perhaps still thinking. Hardly a consolation as her mother traced the outlines of her wasted face, as if to hold on to what remained.

Two weeks later Ada was still alive. Only “physical relief” was of use. Ada was at the stage which Robertson wrote so realistically about in one of his most powerful sermons, “Victory over Death.” She had moved past her human life—only her wracked body remained. Lady Byron listened to the groans of her daughter while outside a little bird sang and in another room Lord Lovelace sat alone. She had bitter thoughts about her lack of Christian charity toward him. She had bitter thoughts about foolish Anna Jameson, who could not have known the condition Lady Byron was in when she sent her last letter castigating Ada’s veracity, erroneously thinking Ada had spoken against her. Then the mother put down her pen. The time had come to tell Ada she was about to die. She went over to her child’s bed and said something about trusting in God, “or words of that kind for I can’t recollect.” What she said as she bid her daughter farewell moved both Dr. West and the nurses to tears, he later told her. Perhaps she had been “a very little Comfort,” she wrote.

Byron, Viscount Ockham, sent to sea at thirteen. Lady Byron suggested naming her first grandson after her husband. He rebelled against the aristocracy and became a railroad worker before his early death.

On Saturday night, November 27, after much agitation and torment Ada was tranquil. Lady Byron left the room to speak with Dr. Lushington, but Lovelace and Greig called her back in.

“Ada lay so quiet and like herself I could not believe it tho all said she was gone.”

Lady Byron took a candle and brought it to her daughter’s mouth to try her breath, and then she brought it to her eyes. She must have kept repeating this motion, for the assembled men had trouble convincing the mother that her child was gone. No matter how often she tested, the candle did not flicker, nor did Ada blink. Finally she stopped.

“Then they wished me to go to my room.” There “every thought turned into one.” Hours later she crept downstairs, where she could be alone with her daughter. Laid out, Ada did not look like herself. She regretted her grandchildren viewing their mother the next day.

“I cannot yet banish the pictures of agonies I have witnessed day after day—and when I have fulfilled some remaining duties here I must seek change,” she wrote. “How much I have learned in the last three months!—how ignorant one seems to have been and how much in need of pardon for that ignorance!”

“If I had loved her less, she would have believed I loved her more. If I had been anxious she should appear to advantage—that she

should be the object of admiration for person and talents—all this would have been intelligible to her as the language of affection, but I could not express what I did not feel. A course consistent with truth might perhaps have been found had I known how little she cared for all that seemed to me the most convincing proof of my affection for her and yet these were not mainly abstract—watching her in illness—providing her with enjoyment that she asked, etc.

“What should I have done?”

“To see clearly too late,” Lady Byron lamented, her “mental suffering” at times transcending her “body’s power of endurance.”

“How weak I have been, tortured and harassed as I was.” She couldn’t stop thinking of “what Might have been.”

Lady Byron left Great Cumberland Place a few days later wishing to go abroad, “but must not I fear. These children bind me. I am ALL to them.”

Ada died at thirty-six, the same age as her father. She had told her mother she would. She was transported to her father’s lost estate, to be buried in the Byron vault in the church outside Newstead Abbey as she wished.

However, rather than the simplicity she requested, the Countess of Lovelace’s coffin was “too ostentatious,” according to Ada’s dear Dandy Bob, who attended. It was massive; “escutcheons and coronets” were “everywhere.” They and the handles were silver. “Lord Lovelace’s taste, not Lady Byron’s.” With regal ceremony, Ada was placed in the chaotic vault of her wicked forefathers’ bones. Some of their remains had been rearranged so that her coffin could touch her father’s, as she wished and he had prophesied:

My daughter! with thy name this song begun—

My daughter! With thy name thus much shall end—

I see thee not,—I hear thee not,—but none

Can be so wrapt in thee; thou art the friend

To whom the shadows of far years extend:

Albeit my brow thou never should’st behold,

My voice shall with thy future visions blend

And reach into thy heart,—when mine is cold,—

A token and a tone, even from thy father’s mould.

Lady Byron did not attend. She had a flight of fancy though, that by Ada’s being buried next to her father, Ada joined hands with him and with her mother, uniting all three through love. The fancy faded quickly, like early snow.

BOTH DR. LUSHINGTON and barrister Greig were kept busy during the winter after Ada’s death. John Crosse expected to be paid off to return Ada’s love letters and Lovelace’s letter of credit. Fleming was expecting Ada’s life insurance to be paid to him. Lady Byron would have none of it, not even “for her.” Mother and daughter “understood each other—She trusted me with the whole truth that I might make it of use, if possible, not make her appear better by proclaiming her virtues or concealing her transgressions.” She likened John Crosse “to a ferocious bird of prey—I fancied him standing over his dying victim cruel and relentless.”

The lawyers were insistent. Not paying these men off would do no good. If things went to court, they’d lose even as they won. “All would become public—nothing could be kept secret—.” It would harm the living as well as the dead, and that included her grandchildren. As the winter progressed, Lady Byron relented, anger turning to acceptance. The life insurance was paid out to Fleming and Crosse received money before destroying Ada’s letters to him as well as Lovelace’s letter of credit.

These threats of suits, these paying off of extortioners after holding out, these many tangles sorted out by her lawyers, were a constant through Lady Byron’s life, and again her critics blamed her exclusively. There was no understanding that being as wealthy as she was and being a Byron whose every action could be scandalous grist for the press made her quite vulnerable to blackmail.

Usually she cared nothing about public opinion, but she was perturbed when Charles Babbage threatened to take her to court. He had been Ada’s executor until Ada replaced him with her mother. Babbage believed Lady Byron had forced her will on her daughter. He was furious that Lady Byron had taken over at 6 Cumberland and that the Wilsons had been summarily dismissed. Babbage also believed he was owed furniture and books. Lady Byron respected Babbage, never linked him with the extortioners who had circled her daughter. She considered him a gentleman and a man of honor and, stunned by his anger, thought they could reconcile. It was not to be.

Two months after Ada’s death she wrote to Robertson: “When I am forced into a position of Antagonism, one of the greatest pains I suffer and the least understood, is the suppression of kind feelings. I am so sorry, even grieved, for those who are suffering from false visions of relative facts, or from internal warfare, that I long to express sympathy, & yet my own course (which I suppose to be that of truth) would be damaged, as people think, by my doing so. Is there no way of reconciling the want to be kind with the duty to be true?”

At first this response appears evidence of that narcissism of hers. She believed cutting off offenders with silence was the right thing to do and that she was forced to suffer isolation because of her rightful convictions. However, in this case the “people” who “think” she would be damaged by not repressing kindness were her lawyers. “I feel this very strongly about poor Babbage,” she wrote to Robertson. “I know intuitively that his passions and his better nature are tearing him to pieces. Is there no voice to say to him—‘Be still!’ It is very hard to be represented by those who act for me, though I cannot say it is without my sanction, seeing no other course open. I do not believe that you or any friend of mine can enter fully into this part of my trouble.”

“You know that she is very peculiar in her views, opinions and actions,” Greig attempted to explain to Lovelace: “These you cannot expect to change. You must therefore take her as she is—and receive and cultivate the opportunity now.” In January 1853 there was a hope of reconciliation, for Lady Byron “proposes that you should make the best of each other as your interests are identical—the children’s welfare.” Greig advised Lovelace not to throw away the opportunity presented and “accept her overture in her own terms, omitting entirely all notice of any other part of her letter which might lead to discussion.”

Lovelace had received no sympathy for his tragedy from Lady Byron. She had admonished him severely for keeping Ada’s debts a secret from her. But what about her? Lovelace had kept Ada’s gambling debts a secret from Lady Byron for one month after learning of them. Lady Byron had kept the pawning of his family jewels a secret from him for over six months, until after Ada’s death, when he was apprised of it through Dr. Lushington. Perhaps in his own anger and grief he couldn’t help himself, or perhaps a characteristic abstruseness added to his own isolated nature and aristocratic pride. Not heeding Greig’s advice, Lovelace wrote to his mother-in-law in accusatory and stiff language, beginning: “No casuistry will convince me that after your unmitigated censure of my concealment from you [of Ada’s debts], you were entitled to suppress the jewel transactions of 1852.”

He had rung the death knell on their relationship.

A few months later Lovelace wrote Lady Byron the most supplicating letter, telling her how much she meant to him and how he hoped for a reconciliation. It might have melted someone else’s heart. Years later son Ralph, who carried animosity toward his father, would wonder if his grandmother’s forgiveness would have made some dent in his father’s increasing severity. Perhaps in the long run nothing would have helped mend the breach. It is doubtful that Lady Byron could ever forgive her son-in-law for not protecting her genius of a daughter, any more than she forgave herself. On Ada’s first birthday she had written:

Thine is the smile and thine the bloom

Where hope might fancy ripened charms;

But mine is dyed in Memory’s gloom—

Thou art not in a Father’s arms!

She realized too late that what Ada had needed from earliest days was to be in her Mother’s arms.