15

15

It would take the boy Lady Byron raised as a son a great portion of his later life to bring that lost chapter of history to light. “She was both father and mother to me,” Ralph, by then Baron Wentworth, wrote of his grandmother, whose name and title he had taken. He had been a bookish, timid lad, with whom his own father Lord Lovelace had little rapport. Ada had wanted heirs, not children, so her shy spare had little to recommend him in the years when mathematics was king and the children a nuisance. His parents were more than happy for his grandmother’s love and care of the little boy with the big brain.

Because of Lady Byron’s progressive educational ideas and her dread of the morals and the bullying encouraged in the fashionable public schools, Ralph became considered an odd boy out by others of his social class: “I have lost I think by the ‘education’ she substituted for a public school. I should not have lamented any loss if I could have been entirely formed and instructed by her—but alas!” he had a succession of dreary tutors. “I was supposed to possess such a vigorous genius as to need a very serious, solitary and depressing education.” All of this was partly his fault, he realized, for he had “the want of power to communicate what was innermost in my heart.” It would appear the apple hadn’t fallen far from the tree.

In chaotic, revolutionary 1848, Ralph’s time at Hofwyl School had been cut short because of safety concerns. Still, experiencing the Alps had a permanent effect. As timid as Ralph was, he had found his enduring passion. “His first recorded climb was the ascent of the Rigi at the age of eight.” When he reached maturity, he returned to the Alps yearly, always preferring rock climbing to “snow work,” and put his flag atop and named more than a few previously unconquered peaks. It was in the solitude of nature that he was most at home and, perhaps like his grandfather Lord Byron, considered he was most himself.

As Lady Byron’s heir, Ralph sought out his grandmother’s sealed papers. Not until 1868, the year before Stowe published in the Atlantic, was he able to obtain “the principal bulk” of them. It had not been easy. He had to wrestle these documents out of the arthritic grasp of an older generation who more or less followed the dictates of the octogenarian Dr. Lushington, who still advised silence as he had through Lady Byron’s life.

Until he obtained these papers, Ralph had been entertaining the idea of writing of his grandmother’s life, “leaving aside as far as possible the story of her marriage and separation.” It would be “the sober narrative of a virtuous life,” the philanthropic life of the older woman he knew. He hardly knew there was an Augusta Leigh. He had asked his grandmother if his grandfather was an only child. “She replied quickly, ‘No, there is his sister, Mrs. Leigh.’ The subject was then dropped; she had spoken without emotion or interest perceptive to me.” This great-aunt of Ralph seemed to him more or less “a stranger to my grandmother, and perhaps my grandfather.” He knew nothing of his mother Ada’s half sister, Medora, until Stowe’s book appeared.

“My grandmother often spoke of my grandfather’s greatness as a poet; she said they had been parted by events which made a separation inevitable, which could not be disclosed.” With his access to the papers, even before Stowe’s article, Ralph had, in his second wife’s words, “to reconcile his own mental picture of the tender guardian of his childhood, the loving mother, the steadfast friend, the living embodiment of generosity and liberal ideas, with the hateful portrait traced of her by her own husband and with his cruel accusation of her as ‘the moral Clytemnestra of her lord.’ And the interest of her character was made more poignant to him by the knowledge that the prejudices born of her bitter experience had been all-powerful in shaping his own youthful life.”

By November 1868, Ralph appeared to have a grasp on the situation and a firm hold on his grandmother’s psychology. An unnamed friend said he knew Augusta to be the cause of the separation, and that it was Dr. Lushington’s influence that helped prevent a reconciliation. This angered Ralph and he wrote to his sister:

“I myself do not believe Augusta was the cause of her leaving B., but that she thought it her duty to shun the moral temptation with which she herself was beset, and she felt horror at the idea B. might become answerable for her moral destruction.” With that, Ralph came as close to the truth as one can. He understood the complexities of his grandmother’s motivation, not only through her letters and “Statements,” but through his blood.

By the time Harriet Beecher Stowe’s article was published in the Atlantic, Ralph had other duties that claimed his time. At thirty he had married a “minor,” Fanny Herriot, her father, a clergyman, consenting. No age of the bride is recorded on the marriage certificate—she was at least fourteen years younger than Ralph. Ralph, given his education, was not wise in the ways of the world; in fact, with women his immaturity appeared endless. Being Baron Wentworth was a major attraction to the fair sex and their parents.

The couple had a daughter, Ada Mary. Fanny bolted soon after, leaving her daughter, taking a lot of jewelry. Everything was hushed up, but Ralph would spend years in financial arrears. Sister Anne was made Ada Mary’s legal guardian and given her to raise. Ralph spent much of his time in the Alps. Lady Byron had made a stipulation in her will that he was to return to England once a year to maintain his inheritance. She knew him well and in a sense that stipulation gave him a modicum of grounding. When Fanny died of tuberculosis a decade later, his sister Anne, but not Ralph, rejoiced.

A free man by the end of the 1870s, his next romance was with a cosmopolitan novelist known to the expatriate artistic community in Rome. Julia Constance Fletcher, an American apparently born in Brazil, was the author of the novels Kismet and Mirage, part of the No Name Series. At the time of her engagement to the Baron, a bawdy joke was circulated that Julia had taken a tumble in the Alps that allowed her to spread her legs in front of clueless Ralph. An anonymous observer called Ralph “the most timid hearted of mortals” and Julia an ugly woman who wore “her meretriciously yellow hair racked up to the top of her head into the latest aesthetical style.” This time sister Anne did not leave her younger brother to his own devices. She hired a detective. There seems to have been no birth certificate, Julia’s parents might not have been married, her mother might have been Jewish! How bad could it get? Lady Anne was adamant.

“Either we must prove your parentage,” Ralph wrote to Julia, or the two of them would have to abandon the idea of being accepted by others. “The worst of this latter alternative would be that if we were married under these circumstances, we should be put to a kind of election and have either to renounce my sister (and probably others) or your mother.”

On January 9, 1880, the Globe had some “Roman Gossip” to report. It appeared “American society in Rome is just now much exercised by the abrupt termination to the matrimonial engagement announced between Miss Fletcher, authoress of “Kismet” and Lord Wentworth. In this transaction no blame is attached to the lady, but the gentleman is highly censured. The Americans love a title, and feel aggrieved that their fair compatriot has been deprived of a coronet.”

Julia wrote to lawyer Ford, whom she knew to be “quite as much Ralph’s personal friend as his family advisor”: “Lord Wentworth is not a boy. He assured me repeatedly that those family considerations which have now betrayed him into so unworthy a position, were for himself, almost non extant. If Lady Byron were still living I should send this letter to her: I should not be afraid of her misunderstanding me.” Lady Byron might very well have understood her, especially when in other letters to Ford pressuring him to intervene, Julia made veiled yet ominous threats of exposing what may have been a lapse in Ford’s fidelity toward his wife. The matter was resolved out of court.

Julia returned jewels and Ralph offered a “sum.” Soon after, Ralph fell in love with Mary Stuart-Wortley. He wrote to her from the Alps, and his letters reveal a sensitivity to her feelings and a sense of his own unworthiness. “I could not write all I do to you to any one else, for with you I feel secure from ridicule.”

He was quite aware he had botched much in his life; he had not lived up to the genius of his youth. There was pathos in his regrets, kindness in his heart, and stirring descriptions of the Alps, the country people, the local guides, the dangers of the invigorating climbs, the scaling to heights not reached before. He pressed lone mountain flowers to Mary in his letters.

Their marriage in 1880 was perhaps the best thing Ralph had accomplished in his life. He was baptized into the Church of England beforehand: “My grandmother told me I had never been baptised, as when I was born my father and mother were Unitarians, who, I believe do not use those words that are necessary for validity. My grandmother disapproved of what they did, or rather of what they did not do, though she did not herself consider any form of words essential. But she thought it was the worst way of attaching importance to words to omit the recognised forms intentionally.” Widower Robert Browning, who never forgave Lady Byron her treatment of Anna Jameson, was a guest at the wedding.

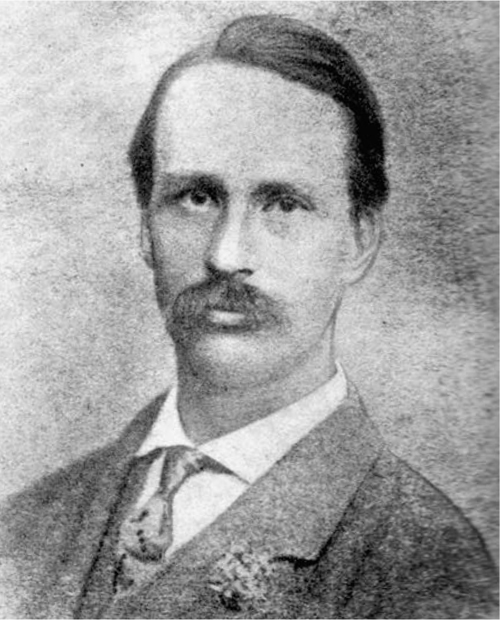

Ralph Milbanke, the intellectually promising grandson and heir of Lady Byron who spent much of his life securing Lady Byron’s immense archives and agonizing over whether he should tell the truth of his grandfather’s incest, which he did in Astarte, 1905.

Though Ralph had not spoken to his father in years, this second marriage to a woman of good family and both aristocratic and literary connections brought Lord Lovelace, who had remarried and had other children, back into Ralph’s life. Ralph’s uneasy reconciliation with his stern father was necessary. He had earlier realized that there were many more of his grandmother’s and mother’s papers in his father’s hands and that he could not tell his grandmother’s story without them. Medora, too, had left papers with his father when she returned to France. “But nothing could be got from Lord Lovelace about the missing papers,” wife Mary wrote.

“Always unapproachable, Lovelace had become doubly so from age and extreme deafness, and he was always particularly hard of hearing on subjects that he disliked. The danger that, if provoked, he might put the papers out of his son’s reach in the future could not be ignored. There was nothing for it but patience.”

The American writer Henry James, a good friend of Mary, had become a good friend of Ralph as well. He visited the couple in their Chelsea home often in the 1880s and witnessed Ralph’s preoccupation with his grandmother’s letters and his need to somehow answer the inaccuracies of Harriet Beecher Stowe. He observed Ralph’s anxiety over the possibility that his unforgiving and ancient father might burn important letters and documents in his possession before he died. If he did so, Ralph would never be able to reconstruct his grandmother’s true story.

What James witnessed became the immediate inspiration for his masterpiece of a novella, The Aspern Papers. It concerned a green trunk of letters from a great American poet, considered the American Byron, to his lover, Juliana Bordereau. The poet was long dead and his love had turned into an ancient, quasi-blind and imperious old woman who guarded her trunk of letters zealously. In James’s tale, the obsessed narrator is not Ralph, but an American scholar who has come as a boarder to Juliana’s run-down Venetian villa in hopes of somehow getting access to the letters: “I had perfectly considered the possibility of Juliana destroying her papers on the day she should feel her end really approach.”

In 1888 when The Aspern Papers was serialized in the Atlantic and then published in book form, Henry James with some justification might have felt that Ralph’s effort to secure the rest of his grandmother’s effects was a lost cause and that the revealing Byron papers held tight by remote, implacable, deaf Lord Lovelace might never reach the light of day. That’s what happens in James’s novella. The blind old woman destroyed the papers of the great Byronic American poet before she died, burning them slowly one by one.

If James thought intractable Lovelace would burn documents before he died, he was wrong. Five years after The Aspern Papers was published, in 1893, old Lord Lovelace passed at the age of eighty-nine. The metaphoric green trunk of letters had survived, and the precious documents were inherited by Ralph. Though for a while Ralph debated accepting his father’s title, he did become the second Lord Lovelace. The estates at Ockham and Ashley Combe devolved to him and for the first time in his adulthood he was free of financial stress.

Friend Henry James might not have been free from stress, however, for the title of James’s novella, The Aspern Papers, was suddenly uncomfortably close to the entire scope of Lady Byron’s enormous archives, called the Lovelace Papers. James had witnessed living history. He had been able to read from the plethora of documents at Ralph’s disposal. He witnessed as well his friend’s conflict: “How to hide the faults of one ancestor without doing black injustice to another, how to suppress truth without adding to a mountain of lies.” Ralph knew by then that Harriet Beecher Stowe had been right concerning the incest and the birth of Medora, but the truth caused her to turn his grandfather into a one-sided villain and his grandmother who raised him into an all-suffering saint. For Stowe the sexual relationship between the siblings had been the reason Lady Byron had left her husband. How could Ralph rectify this false position and still somehow not deal with the incest?

Wife Mary remembered “listening for the hundredth time with indescribable weariness, and in secret revolt at the sacrifice of his life, at the constant waste of his talents and energy in the effort to solve an insoluble problem and at the hateful atmosphere of the miserable story which he was compelled to have constantly in his thoughts.” Pacing the room, Ralph called out: “Oh! if I could have peace!”

“There never will be peace till the truth has once for all been acknowledged!” Mary exclaimed, thinking out loud.

Ralph “wheeled round” and faced her: “Ah! You think so, do you?”

“And I realized that my words had confirmed the thought that was already formed in his mind.”

From then on, the only question was how the truth of the Byron marriage would be told. Ralph had spent years, decades actually, reading and annotating his grandmother’s archive. As much a scholar—pedant?—as Henry James’s character in The Aspern Papers, Ralph tended toward too much overly erudite information. “He remembered too well how the public had seized on every detail of Guiccioli’s Recollections, as well as on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Lady Byron Vindicated, and dreaded a similar succès de scandale,” his wife wrote. His only desire was “to put the truth beyond question.” In order to avoid “newspaper notoriety, and above all the possibility of making money,” from his grandparents’ lives, “he decided to print the book privately and to circulate it as a gift among friends and prominent persons in the literary world.”

Here too he was like his grandmother. He wanted in effect to tell without telling. Ralph was forced to print 200 copies to claim copyright, otherwise he would have printed fewer. Many remained with the family, a few sent to select libraries. Presentation copies went to intimates and literati such as Anne Thackeray, Vernon Lushington, Lady Gregory, William De Morgan, Sydney Cockerell, Algernon Swinburne, and to Henry James. The truth is in Astarte, albeit in a convoluted fashion. Little public notice was taken of his book, as Ralph had wished, though many of his literary friends responded, the longest letter coming from Henry James:

Let me tell you at once that I am greatly touched by your friendly remembrance of my possible feeling for the whole matter, and of your own good act, perhaps, of a few years ago—the to me ever memorable evening when at Wentworth House, you allowed me to look at some of the documents you have made use of in “Astarte.” Ineffaceably has remained with me the poignant, the in fact very romantic interest of that occasion. And now you have done the thing which I then felt a dim foreshadowing that you would do—but the determination of which must have cost you.

James saw his friend’s book as “an incantation out of which strange tragic ghosts arise.” But just as Ralph evoked “ghosts,” he sent them back into their shade never to rise again. “Great is the virtue of History—when it has waited so long, and so consciously to be written, and to be enabled to proceed to its clearing of the air.”

Ralph’s justice to his grandmother had “the same final and conclusive character.” Ralph had not “yielded to any insidious but considerable temptation to dress her in any graces, in any shape of colour, whatever, not absolutely her own. To have spoken for her so sincerely and with such effect, and yet with such an absence of special pleading—I mean with so perfectly leaving her as she was—can’t have been an easy thing, and remains, I think, a distinguished one. Clear she was, and you have kept her clear; and amid the all too heavy fumes one puts out one’s hand to her in absolute confidence. I think her spirit somewhere in the universe, must by putting out its hand to you!”

James even understood Lady Byron’s at times convoluted prose style, beyond what Anna Jameson called its “strangulation.” The subtleties involved in its mixture of psychological penetration, empathy for others, narcissism, and strong self-will spoke to him. Lady Byron, when dealing with complex issues of the heart, particularly when it came to her sister-in-law Augusta, wrote in what could be called the patois of the cultured aristocrat. Thomas Carlyle who had little good to say of anyone or anything—though he did like Lady Byron—was overwhelmed by what he called the perfection of the manners of the English aristocrat. In that tradition, Lady Byron was able to say without saying, but her meaning both literarily and psychologically spoke out to Henry James.

Henry James saw a beauty in the complexity of motives that might have seemed to others a failure to communicate. He did not reduce this complex woman. Influenced by Lady Byron’s magical papers, including many letters to and about Augusta Leigh, James incorporated in his late style a method of arriving at both emotional and moral truth reminiscent of Lady Byron’s aristocratic indirection. He could look under the piety of Lady Byron’s expression to the submerged “ghosts,” to the darkness in her heart.

MARY BELIEVED the five years her husband spent writing Astarte, published in 1905, “were the happiest of Lovelace’s life.” The doubts that plagued him for thirty years were cast away: “When I think of those who paced the garden at Ockham with him on those happy summer afternoons, I see the well beloved figures of W. H. Lecky, Henry James, William de Morgan, Lord Courtney.” When he saw his book in print in 1905, Ralph sighed with relief and told Mary he hoped never to think or speak of it again.

In the late summer of 1906 the couple hadn’t sought out the cool pines of Ashley Combe but remained at Ockham. One very hot August morning, “the head-woodman came to report damage done by mischievous boys in Lovelace’s favourite plantation.” Extremely angry, Ralph rushed into the hot sun to see the destruction caused. That afternoon he and his wife had a delightful visit from a friend who sat with them on the terrace and was amused as usual by the goings-on in their aviary: “The love-drama between Pierrot, the green Amazon parrot, and Rosy Talbot, the pink cockatoo.” As the guest left, Ralph made a joke about Pierrot’s ardent courtship. An hour later Ralph was found out on that terrace, facedown in the twilight. “He had passed away without fear or pain.”

The newspapers took more account of Astarte after Ralph’s sudden death, but, of course, that soon became yesterday’s news.

For all of Ralph’s own eccentricities of style and documentation, he had presented an extraordinary balanced portrait. He regretted hearing his grandmother often say “Happiness no longer enters into my views.” He considered it a shame that she fell from “the world of intellect and fashion to the world of Methodists, Quakers, Unitarians,” to “reformers” who distrusted “the pleasures of this world.” His grandmother herself joked that one day she might revolt from the dismal company of good works. But she never did. Instead, Ralph wrote, “She renounced the world of enjoyment, like the founder of a severe monastic order,” and would have forced everyone under her power “to live a life of Spartan self-denial, and devotion to a somewhat despotic philanthropy.”

She often told her grandson that she considered “Be Yourself” a better precept than “Know thyself.” She was herself, at the same time as she consciously splintered off from the dark part of herself.

At twenty-two, she had married a great poet. When that marriage ended, she had a daughter by him and a deep, complex relationship with his sister. She had sworn to Byron that she would “be kind to Augusta still,” and she turned the darkness of her jealousy into a determined effort to keep sister and brother apart. However, it wasn’t jealousy alone; she also believed she was saving brother and sister through her silence, and that she protected her husband’s reputation through her long life. During that life, she raised a daughter, Ada, Countess of Lovelace, who would become world-famous more than a century after her tragic early death. She attempted to influence the tortured life of Lord Byron and Augusta’s daughter Medora Leigh, who bore a striking resemblance to Byron. She raised as well her grandson Ralph and just about raised and certainly loved her granddaughter Anne and her grandson Byron, Lord Ockham, who went his own Byronic way and died two years after his grandmother.

Lady Byron expressed love the way she knew how, through deeds. She advanced the working poor through the Infant Schools and Co-Operative Schools she founded on her shores. She was also the silent benefactor of more unfortunate girls and women in England than we will ever know. Through her friendship with Harriet Beecher Stowe she aided runaway slaves to escape to England after the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. She spent all her money on others, and the reason she remained wealthy in spite of this was that she understood the future of the railroads grandson Byron was helping to build and had, in managing her estates, the business acumen of her mother and her aunt, Lady Melbourne. She reaped as she sowed.

Two hundred years have passed since that fateful one-year marriage that has entered literature and social history in so many ways. Two hundred years since the birth of Ada, Countess of Lovelace. And almost two hundred since Byron died at Missolonghi. Lady Byron lamented, put on widow’s weeds, and was haunted that her husband’s last words to her were garbled by fever and could not be discerned. What he wanted to tell her was lost. Twenty-five years later she would lament that Augusta Leigh’s last words to her were too feeble to be heard. A second message lost, she wrote.

Who was this woman? We can see parts of her through Augusta Leigh, Anna Jameson, Walter Scott, Joanna Baillie, the Brownings, Robertson of Brighton, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry James, Ralph Lovelace; other parts through Byron’s searing poetry. Through her eventful life we can see her struggle with the complexity of her motives in her letters, her poetry, her “Statements,” her “Conversations,” all of which come down to us. So do some delightful personal letters that shine with that “attic wit” Lord Byron satirized. Speaking of her granddaughter: “Anne said one day with some truth as well as humour, ‘This world seems to me one great Dining-room.’! She could not see all the philosophy of what she was saying.”

We can experience Lady Byron’s humanity most fully in her complex relationship with her “two daughters,” one born to every advantage, the other raped as a child and betrayed by her own mother. She wasn’t a perfect mother; neither was Ada or Medora. Ironically, like Medora, she was a single mother. She raised Ada the best she could and not only learned but accepted her failures at the end, at the same time that her unconditional love shone through in unsentimental yet constantly “cheerful” caregiving to her dying daughter. She raised grandchildren who loved her, a grandson who devoted his life to reclaiming her papers, and a granddaughter who stayed with her till death.

Anna Isabella Noel Byron sealed up, did not destroy or alter, those papers Ralph saved. They tell her truth both in darkness and in light. Though she was ill adept at facing the darkness in her own soul, she did not shield herself from posterity. “If the world is cruel, let it alone,” she snapped at Anna Jameson. Lady Byron took her own advice. She made no attempt to censure records and never attempted to shape her life in order to find favor with the world. She was herself. She remained herself. Perhaps the time has come to realize that history is also her story.