5.

I’m the Boss. And now everybody is waiting for me to tell them what to do. Which is hard, because I just don’t know, seeing how I’ve never been a Boss before.

Patsy Cline won’t look at me for some reason. Vera Bogg won’t stop looking at me, and I really wish she would.

“What about my outer-space idea?” says Marcus.

Alexander says, “What about monster trucks?”

I give them both a look that says, When Was the Last Time You Saw Mother Goose on a Monster Truck? And then because I can see Marcus and Alexander aren’t so good at telling what different kinds of faces mean, I say, “When was the last time you saw Mother Goose on a monster truck?”

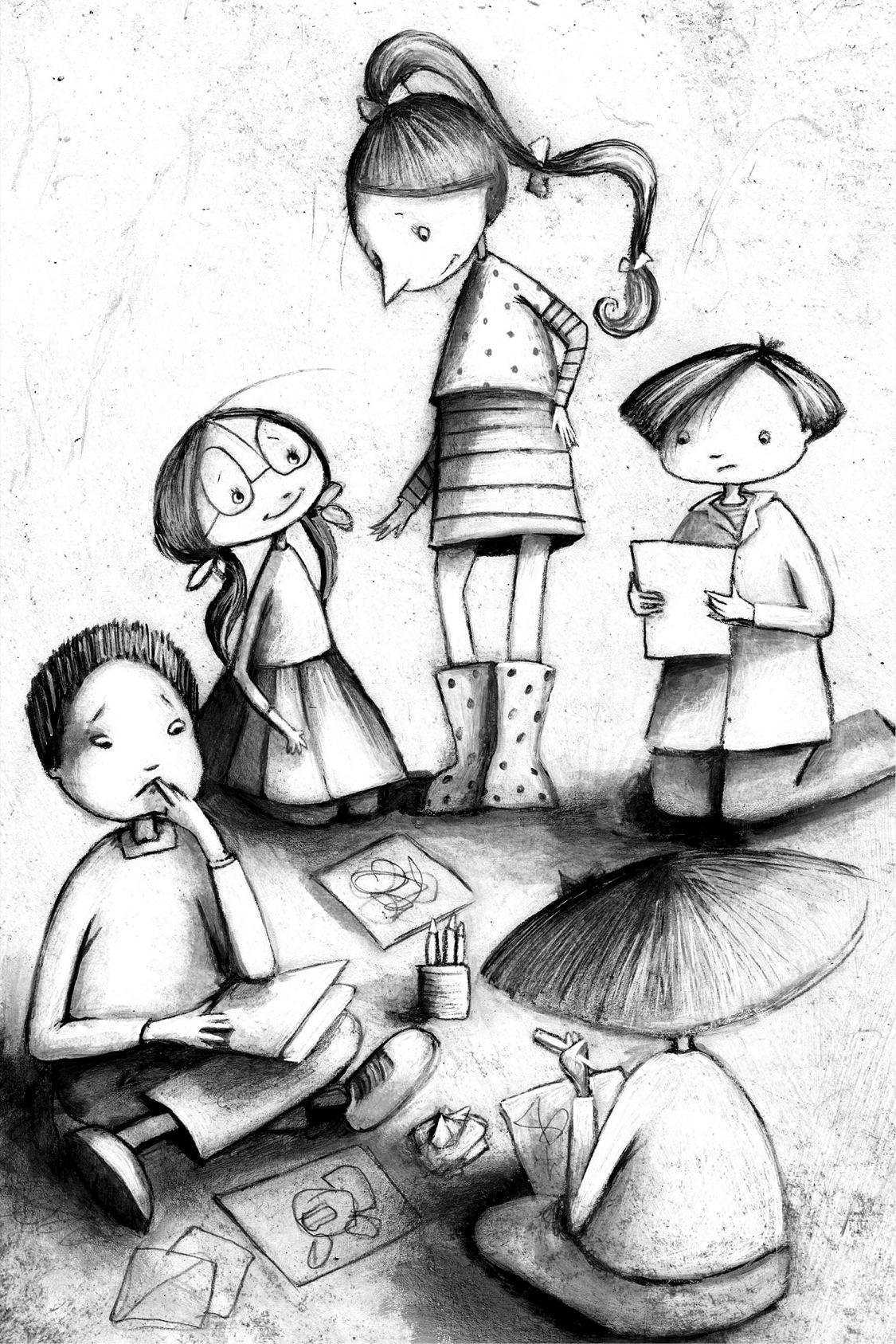

Alexander scratches his head like he’s trying to remember. And the next thing I know, everybody is talking about what they want in the mural and isn’t the Boss supposed to be the decider? I look to Mr. Rodriguez for help, and finally he puts down his Art Now magazine and says, “Why don’t you each draw out what you’d like the mural to look like, so Penelope can see.” Then he says he needs to step out for a minute but will be back.

I tear blank pages from my drawing pad and hand them out. Everybody gets busy with the drawing, and because I’m in charge, I do what Miss Stunkel does: walk around and judge everybody’s work.

It’s bad. And I’m not just saying that because I’m trying to be like Miss Stunkel. Which I would never want to be—because, well, her finger for starters. I’m saying it because it’s real true. Marcus won’t give up on his spaceships. Alexander isn’t drawing at all. Instead, he has written in big angry letters: IF WE CAN’T HAVE TRUCKS, I QUIT! Birgit is covering her drawing with her arms and doesn’t want me to see. Patsy Cline is drawing something, but I can’t tell what because it’s the size of a flea. She tells me she’s one hundred percent certain it’s not a flea, though. And then she looks mad at me for asking twice.

To my surprise, Vera Bogg is not drawing a snowman. She is drawing a girl in a frilly dress with ribbons and a wide, lacy hat. There’s a sheep, too. With ruffles. Vera catches me looking and then explains that she’s drawn Little Bo Peep but the sheep isn’t lost just yet. She says that if the sheep was lost and wasn’t in the mural, nobody would know that Little Bo Peep was Little Bo Peep. They might think she was Mary Had a Little Lamb. Which is a whole other Mother Goose rhyme altogether. “And it wouldn’t be right to confuse the elderly.”

I’m about to give her a look that says, You Make My Head Hurt, Vera Bogg, when I see Nila Wister roll by the door in her wheelchair.

Maybe it’s because I’ve been voted the Boss and am on my way to be a not-dead famous artist, but all of a sudden I feel brave. “Keep drawing,” I tell everyone. “I’ll be right back.”

I follow Nila Wister down the hall. Past the people in their wheelchairs, who are still just sitting as far as I can tell, and as I hurry by, I can feel their eyeballs on me and I feel bad all of a sudden for having legs that work and for not being old like them.

My feet don’t go as fast as Nila’s wheels do, so I don’t catch up with her until the nurse rolls her into a room. The door is open, but I knock anyway because being polite is the first step in getting your stuff back.

Nila has her back to the door and says, “I don’t need any more pills. Go away.” She waves her arm, and when she does, the trinkets on her wheelchair swing.

“I don’t have any pills,” I say. “Or candies. Or any more paintbrushes or bags.” I say the last part just in case she has plans to steal something else of mine. She turns her ancient neck to look at me, and when she sees me, she doesn’t invite me in. But she doesn’t say, “Go away, you’re as unwanted as a warty toad,” either. So I take a step inside.

The walls in Nila’s room are covered in posters. Carnival posters of elephants and clowns and people in old-timey outfits diving into water. There’s even one of a strongman, with giant muscles, so strong he’s lifting a planet over his head. One poster has a Ferris wheel in it, and a roller coaster. And above her dresser, there’s one of a lady with a scarf tied around her head and big hooped earrings. There is something about this lady, something I’ve seen before, but I don’t know what.

“What are all these?” I ask.

Nila looks at me sideways and then at the posters. “Mine.”

This is something Terrible would say. “I know they are yours,” I tell her. “But I mean, what do you have them all for?”

“My life,” she says.

I don’t know what she means exactly because what does her life have to do with a bunch of posters from a carnival? I stare at the muscle-y man and wonder if his arms ever get tired of holding up that world. I can almost see him wink at me as he answers, “Only when it rains, little darling.”

The bottom of some of the posters have the words “Coney Island” on them. “Is that where ice cream cones are made?” I ask.

Nila frowns. “That some kind of joke?”

I shake my head. “Nope. I never joke about ice cream.”

“Me neither.”

“That’s a real place then?” I say. “Coney Island? Because it sounds made up.”

Nila flaps her lips and then tells me that if I plan on sticking around, I should come stand in front of her so she won’t get a stiff neck, or else I should turn her chair. I grip the handles of her wheelchair and pull her toward me and around until she’s facing me. When I do, she says, “That’s better,” and then, “It’s a dream.”

I don’t know if that means Coney Island is a real place or it isn’t. So I tell her about a dream I had once that we lived in a house, not an apartment but a real house, and it was made out of cotton candy. “The whole thing,” I tell her. “The walls, the roof, the couch, the refrigerator, the fireplace, the beds, the pillows, the dishes . . .”

“I get the idea,” says Nila.

“Well, every time I tried to go into a different room, I’d sink into the floor. You know, because even the floor was made out of cotton candy. Just like the walls and the roof and the couch . . .”

She rolls her eyeballs at me, I don’t know what for. Then she says, “Is that all?”

“Pretty much,” I say. “I woke up after I ate the shower curtain.”

She says, “Humph,” and then nothing else.

“Is Coney Island really like that?” I ask.

She nods. “Even better.”

“Then how come you’re here?” I say. “I would never leave a place like that.”

She gives me a look that says, You Don’t Know Anything, Little Girl. And then she says, “Why are you here?”

“To paint a mural down the hall, remember?” I say it real nice because it’s not her fault that she’s old and doesn’t remember things. “I’ve been elected the Boss, sort of.”

“No,” she says. “Why are you here?”

Oh. I quick do a search for my stuff. “I wanted to know if you are done with my paintbrush. And my bag.”

She shakes her head.

I say, “I think you took them by mistake.” Sometimes you have to lie to be nice when you are trying to find stolen property.

“You got any candies?” says Nila.

I tell her no.

Then Nila Wister looks me right in the eyeballs and screws up her tiny mouth. She says, “Then I’m not done.”

Good gravy.

“When do you think you will be done?” I say.

“When do you think you will have some candies?”

“Maybe tomorrow?” I say, hoping this is the right answer.

Nila waves her hand at me like she wants me to go. “We’ll see,” she says.

On my way out, I look again at the poster of the lady with the scarf. There are words in fancy letters above her head: “If You Wish to Find Which One Is True, It Is the Fortune Lady Who Will Tell It to You.” The look in the lady’s dark eyes says, I Will Tell You Your Dreams. And that’s when I know.

“That’s you,” I say, pointing. “You are the Fortune Lady?”

Nila flaps her lips at me. Which I take to mean, Yes Indeedy, I Am.

“What kinds of fortunes do you tell?” I ask. “Good or bad ones?”

“You can’t have one without the other,” she says. Then before I know it, she fixes her eyeballs on me like she’s looking deep inside, seeing things that I don’t know are there. She looks at me so long and so hard that I think she could even beat Patsy Cline in a staring contest. Finally, when I think she might have gone to sleep with her eyes open or maybe even died, she says, “You’ve lost something.”

Some fortune lady she is. I put my hands on my hips. “My paintbrush and bag. Which you already know because you took them.”

Nila Wister rolls her old, dark eyeballs at me. Then she tells me to hush and that she’s not talking about my dumb old paintbrush or bag. She blinks at me a couple of times, and says, “You’ve lost someone.”

I gulp.

“And that’s not all.”

“What’s not all?” I ask.

“There’s trouble about.”

“About what?”

“You,” she says.

I whisper, “The Bad Luck.”

“Yes,” she says, sniffing the air, “I can smell it.”

I don’t say anything. Because what do you say to a Fortune Lady who can see inside you? Who knows what you know, but more of it. And who can smell the Bad Luck. I stick my big nose in the air and sniff, too. But all I can smell is arthritis cream, the same kind Grandpa Felix uses.

“Are you sure?” I ask.

“You don’t smell it?” She looks at my big nose and then raises one eyebrow at me, disappointed.

I sniff again and shake my head. “What does the Bad Luck smell like?”

But before Nila can answer, a nurse comes into the room and says it’s time for lunch.

“I’m not hungry,” Nila growls.

“Oh, Ms. Wister, don’t be such a grump,” says the nurse. “You’ve got to eat.” My stomach rumbles, and the nurse must hear it because she looks at me and says, “Who’s your little friend?”

“Nobody,” I say quickly, heading for the door. But before I go, I say to Nila, “Does it smell like fried onions?” Because if I was the Bad Luck, that’s what I think I would smell like.

Nila raises her eyebrows at me. Which I know means, Yes, as a Matter of Fact, It Does. And then I race down the hall toward the activity room, my nose searching the air for any sign of the Bad Luck. On the way, a smell stops me cold for a second, but thank lucky stars, after a couple of more sniffs, I know it’s just the spaghetti and meatballs from the dining room.

When I get to the activity room, something stinks like pink. Vera Bogg has got a big smile on her face. She says, “Penelope, you’re back. While you were gone, we voted again.”

She says it like I’ve been gone for a gazillion years, like they all thought I was dead and now have moved on with their lives and can barely remember some girl with a big nose who might have been in charge a long, long time ago.

“But I was only down the hall,” I say.

“Still.”

“But I’m the Boss,” I say, wishing I had my clay tiger with me. Vera’s ankles could use a good bite.

“We know,” she says, “but you were gone, and we needed to decide something and there was nobody here to do it.”

I tap Patsy Cline on the shoulder. “Where’s Mr. Rodriguez?”

She says in a soft voice, “Wrangling up our lunch.”

“What was the vote?” I ask.

Vera Bogg says that they decided that everybody’s ideas should be in the mural. Even the monster trucks. Then she tells me that since I’m the Boss it’s my job to make them Mother Goosey. She hands me the drawings they did while I was gone. Monster trucks, spaceships, unicorns, and asteroids. I can’t look at any more.

If Mister Leonardo was here, he would surely say, “You have been cursed for certain, and you must find a way to break it before your beloved masterpiece is ruined.”

And he would be right.