It would therefore be appropriate to view global jihadism as a tremendously successful entrepreneurial initiative. From a corporate branding perspective, or the business of helping a corporation to create an enduring emotional tie between itself and its consumers, al-Qaida provided a perfect vehicle to “sell” global jihadism.1

On March 3, 2008, a suicide bomber detonated himself on a U.S. military base in Kabul, Afghanistan. The attack received relatively little media coverage at the time, probably because in neighboring Pakistan a wave of suicide bombings had claimed the lives of more than a hundred people over the previous three days.2 The attack finally received attention weeks later, when militants released a DVD of it, in which the face of Maulavi Jalaluddin Haqqani is juxtaposed to the huge explosion caused by the bomber. Haqqani had been a leader of the Afghan resistance against the Soviet Union in the 1980s and later became one of the most important commanders of a resurgent element of militant groups often referred to collectively as the Neo-Taliban. These groups operate out of Afghanistan as well as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of neighboring Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province (renamed Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in April 2010).3

Haqqani’s forces became one of the most significant elements of the Neo-Taliban starting around 2006.4 His group is believed to have been responsible for an operation against the Indian embassy in Kabul on July 8, 2008, that is one of the most dramatic by the Neo-Taliban insurgency. The attack killed 54 people and injured nearly 140, most of them simply waiting outside the embassy gates to obtain visas. U.S. and Afghan officials credited the attack to Haqqani, with some insisting that it was carried out with the assistance of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI), whose presumed agenda included destabilizing the Afghan government as well as striking at India, Pakistan’s long-term adversary.5

The embassy bombing received greater attention than the base attack because of the number of fatalities it inflicted and the volatile history of relations between India and Pakistan. The first attack, however, is more revealing of the ways in which suicide bombing had changed and continued to change after the 9/11 attacks. This operation illustrates the spread of suicide bombing into Pakistan and Afghanistan, where suicide attacks were generally unheard of prior to 2001. In addition, the marketing of the attack reveals the Neo-Taliban’s connection to the global jihadi movement—and indeed the rest of the world—through technology.6 The identity of the March 3 bomber points to the effectiveness of the movement’s appeal. Unlike the embassy bomber, a Pakistani citizen, the March 3 attacker was a German citizen of Turkish ethnicity named Muhammad Beg. Apparently, Beg voluntarily traveled from Turkey to Pakistan to join the Haqqani network and then became a human bomb.7

The first groups that trained and deployed suicide attackers used their bombers for tactical as well as strategic purposes, but the globalized martyrdom of al Qaeda has lost much of its strategic value and instead now tends to serve a shorter-term, demonstrative purpose—recruiting alienated young Muslim men to the movement by selling them a form of identity myth that makes sense of their frustrations and anxieties. While the global reach of electronic communications has allowed the movement to effectively mobilize the small percentage of the Muslim world predisposed to al Qaeda’s message, the global jihadi movement has remained marginal because it offers nothing of substance to the majority of the world’s Muslims.

On September 9, 2001, two al Qaeda operatives posing as journalists were granted an interview with Ahmed Shah Massoud, leader of the Northern Alliance, at that time the primary opposition to the Taliban in Afghanistan. They hid a bomb in one of their camera cases which they then detonated during the course of their “interview,” killing themselves and injuring Massoud, who died the following day.8 This was possibly the first suicide attack to take place in Afghanistan.9 Throughout the many years of the Soviet occupation and subsequent Afghan civil war, with their attendant violence and atrocities, suicide bombing never established a foothold in this part of the world. Only after 2004 did suicide bombing become a common occurrence, imported, and in some cases imposed on the local population, by remnants of al Qaeda and its allies in the global jihadi movement.

In the first years after the 9/11 attacks, the war in Afghanistan appeared to be a decisive victory for the United States and its allies. When Hamid Karzai, then seen as a hard-working politician with a domestic constituency and international support, won the presidency of Afghanistan in 2004, his election was held up as an indicator of progress in the building of an Afghan state. Lacking a firm commitment to security and reconstruction, however, the new Afghan government proved itself to be largely ineffective. The warlords of the 1990s reemerged, funded by explosive growth in the opium trade. Drug money left the warlords wealthier than the government, and Karzai was extremely ineffective in his dealings with them.10

Meanwhile, the people of Afghanistan found themselves trapped between two very different adversaries fighting with different types of precision weapons, which caused significant civilian casualties in spite of (or in some cases because of) the intelligence used to guide the weapon interactively to its destination. The NATO powers lacked the numbers of troops necessary to police the entire country effectively, so prior to 2009 their forces combated the insurgency of the Neo-Taliban using airpower; few alternatives existed. From January to August 2008, NATO forces conducted 2,400 air strikes in Afghanistan.11 The use of even the most accurate precision-guided munitions carries with it the risk of causing unintended civilian casualties, so when the number of air strikes is high, civilian deaths become a certainty.12 As in Iraq, the use of airpower by U.S. and allied forces in Afghanistan was sometimes counterproductive in that it inadvertently solidified alliances between the local population and militant groups despite underlying ideological differences.13

This combination of factors created a climate conducive to the resurgence of the Taliban. Although typically called the New Taliban, Neo-Taliban, or just Taliban, the opposition to the Afghan government and its foreign allies is less an organized movement than a broad, diverse range of groups with different ideologies and agendas across the spectrum. The outfits operating in the south of Afghanistan and into Baluchistan tend to consist of remnants of the original Taliban. Their orientation is local, and they are nominally governed by a twenty-three-member shura council headed by former Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar in Quetta, in Pakistan’s Baluchistan province.14

To the north and east, in the tribal regions of Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the picture is more complex. Here remnants of the insurgency against the Soviet Union have reestablished themselves, sometimes with the complicity of Pakistan’s ISI.15 Members of the Taliban and al Qaeda were welcomed by tribal groups in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as they fled Afghanistan during 2001–2002. Al Qaeda reconstituted and continues to play a role in the local insurgency in addition to encouraging and supporting terrorist attacks around the world.16 Militants known collectively as the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), or Pakistani Taliban, from the tribal regions, have launched their own insurgency against the Pakistani state. They are more closely affiliated with al Qaeda than with other militant groups in the area.17

The original Taliban was militantly anti-technology—they smashed TVs and outlawed photography—but elements of the Neo-Taliban have published online journals, shot, edited, and marketed DVDs, and used the Internet for publicity and recruitment.18 Many of the most technology-savvy elements of the Neo-Taliban are the ones most closely connected to al Qaeda and its global agenda. This use of technology to fuse the local Afghan insurgency with al Qaeda’s global agenda allowed for the importation of suicide bombing into Afghanistan and then into Pakistan.

Even after the spectacle of 9/11 and the rapid destruction of the Taliban government, Afghan militants did not immediately turn to suicide attacks. Only in 2005 did suicide bombings become a staple of the Neo-Taliban insurgency. Brian Glyn Williams suggests two reasons for the delay. First, suicide attacks were fundamentally alien to the culture of the Pashtun people, who make up much of the Neo-Taliban, and second, suicide bombing was not seen as being powerful enough to redress the imbalance of forces between the Neo-Taliban and its adversaries.19 Thus relative advantage and cultural compatibility were both lacking.

Remnants of al Qaeda, which included holdovers from the pre-9/11 area and veterans of other theaters, particularly Iraq after 2003, worked diligently to create a climate into which they could import their preferred type of weapon. By late 2003 they could point to successful attacks in Iraq, such as the bombing of the UN building in August 2003, as evidence that suicide attacks were the only way to combat the Afghan government and its American sponsors effectively. They made dramatic use of the video propaganda produced by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in Iraq, dubbing videos of bombings, suicide attacker testimonies, and executions into Pashtu. By 2004 a local al Qaeda operative had begun producing Afghan-specific videos with titles such as “Pyre for the Americans in Afghanistan.” The first few sporadic attacks in 2003 and 2004 were carried out by Arabs already indoctrinated in the culture of martyrdom and served as trial runs to demonstrate the effectiveness of suicide attacks to the skeptical Pashtuns.20

This marketing campaign paid off within two years. Mullah Omar, who had previously condemned suicide attacks, reversed his position and laid the groundwork for the ideological acceptance of suicide bombing in Taliban culture. With suicide attacks no longer taboo, Neo-Taliban fighters began to embrace them, calling suicide bombers “Mullah Omar’s Missiles” and “our atomic bombs.”21 Mullah Dadullah became the local Taliban commander most enthusiastic about the use of suicide bombers. In early 2004 Dadullah reportedly sent a team to train with Zarqawi, an old acquaintance from the latter’s Afghan years, and the next year Zarqawi sent a three-man delegation to Dadullah to present further video material justifying suicide attacks. With this direct transfer of know-how, Dadullah was able to begin training suicide bombers systematically in his stronghold in Pakistan.22

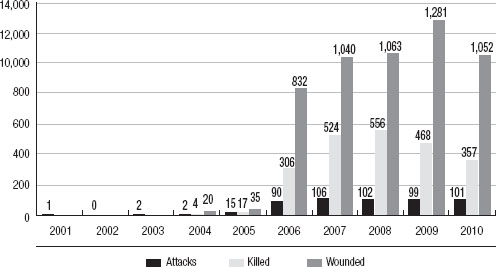

There was significant resistance to this new form of weapon, and many Pashtuns seem to have been reluctant to become suicide attackers. For the most part, as was the case in Chechnya, bombers were not recognized as heroes by the local populace, and public support for suicide attacks remained low.23 One peculiarity is the relative ineffectiveness of Neo-Taliban suicide bombers who collectively killed far fewer people per attack than suicide bombers in other areas of conflict. This can be partially attributed to target selection by the Neo-Taliban attackers. For the most part, at least through 2007, they tended to focus on military and political targets, which were well defended, rather than mass-casualty attacks against civilians, as was common among Iraqi suicide bombers.24 In all, there had been 518 suicide attacks in Afghanistan as of December 31, 2010, killing 2,232 people at an average of 4.3 fatalities per attack, less than half the average number of fatalities per attack in Iraq (see Figure 8.1).

The poor operational record of Neo-Taliban suicide attackers also reflects the low quality of recruits and the training they received. Because of the unwillingness of many Pashtuns to embrace suicide bombing, the pool of recruits from which Neo-Taliban leaders can choose has been limited. A significant percentage of Neo-Taliban suicide attackers have had physical or mental disabilities and have likely been coerced or misled in some way. Many abandoned their attacks at the last minute, demonstrating a lack of ideological commitment. Some were detonated by remote control.25

FIGURE 8.1Suicide Attacks in Afghanistan, 2001–2010

Sources: For 2001 through 2003, United Nations Assistance Mission to Afghanistan, “Suicide Attacks in Afghanistan, 2001–2007,” New York, September 2007, 42; for 2004 through 2010, Worldwide Incidents Tracking System, National Counterterrorism Center, wits.nctc.gov (accessed November 12, 2009; April 1, 2010; and April 1, 2011).

The movement also relied on children, even twelve years old or younger, to carry out its suicide attacks.26 The advantages for the use of young people are straightforward. The constant violence that Afghanistan has endured has left thousands of children orphaned.27 Since they have no families to be consoled, it is easier for militant groups to use them in a more overtly coercive manner—without the corresponding social backlash—than has normally been the case in suicide bombing. The disadvantages, of course, are diminishing returns at the tactical and strategic levels. The poor training and abilities of such bombers lead to marginal operational capabilities, and their lack of social standing makes it difficult for the Neo-Taliban to use their bombers to generate legitimacy in the long run.

The introduction of suicide bombing to Pakistan quickly followed its appearance in the Afghan theater. One suicide attack took place in 2005, followed by five in 2006 and then by at least forty-one in 2007, including the assassination of former prime minister Benazir Bhutto on December 27, 2007. The following year, there were fifty-eight suicide attacks, including the devastating strike on the Marriott Hotel in Islamabad on September 20 that killed sixty people and injured more than two hundred. Such was the physical and symbolic devastation of this attack that within Pakistan the media referred to the blast as “Pakistan’s 9/11.”28 The original Taliban had served several Pakistani national security goals by providing strategic depth against India and serving as a training ground for producing militants that could be sent to pin down Indian forces in the disputed parts of Jammu and Kashmir. When al Qaeda drew the U.S. military into southwest Asia, it ruined years of planning by the ISI and left the organization scrambling to pursue a consistent policy. It now seems that in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the ISI played a double game, supporting U.S. goals by rounding up al Qaeda suspects but at the same time hedging its bets by sheltering Taliban leaders.29

This policy was only partially successful, as within the Neo-Taliban movement attitudes toward Pakistan and the ISI range from cordial to adversarial. Allied factions, such as the Haqqani network, operate openly in Pakistan with the de facto blessing of the army.30 Hostile factions, including the remnants of al Qaeda and its most closely allied factions, have been at war with the Pakistani government as much as they have been with the governments of Afghanistan and the United States. In 2004 the Pakistani army invaded the tribal region of South Waziristan in an effort to impose control and in doing so alienated many local tribal leaders, some of whom then formed the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan, which became openly hostile to the Pakistani military and state.31

In July 2007 the government of Pakistan stormed the Lal Masjid, a bastion of Islamist criticism of the Pakistani government, after a tense standoff with militants. By the end of the siege, approximately one hundred people had been killed.32 The attack on the mosque triggered a breakdown of a tenuous cease-fire between Neo-Taliban factions and the Pakistani government, after which the militants responded with ferocity. Of the forty-two suicide attacks that took place in Pakistan in 2007, thirty-six occurred after clashes erupted at the mosque on July 3. Overall, Neo-Taliban forces and their al Qaeda allies killed 250 members of security forces in the months immediately after the siege.33 In October 2009, as the Pakistani army renewed its offensive against Taliban factions, they responded with an especially brutal campaign of suicide attacks, many of which targeted civilians. At least five suicide bombings took place that month, the last of which was a particularly deadly attack in a bazaar that killed at least 120 people, most of them women and children.34

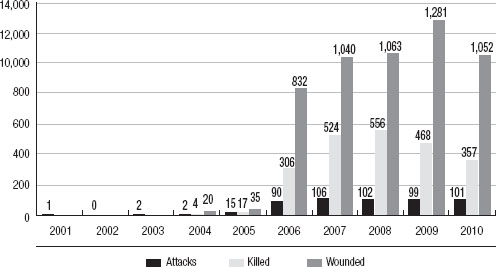

In all, there had been 239 suicide attacks in Pakistan as of December 31, 2010, killing 3,759 people and injuring nearly 10,000 (see Figure 8.2). Many of these attacks were claimed by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. The number of fatalities per attack, approximately 15.7, is testimony to the high lethality of suicide bombing in Pakistan due to the militants’ willingness to hit vulnerable civilian targets. As was the case with Afghan suicide bombers, many Pakistani suicide attackers were young boys who had been orphaned or had physical or mental disabilities that made them particularly susceptible to indoctrination and coercion by militant leaders. One Taliban leader asserted, “Children are tools to achieve God’s will.”35

FIGURE 8.2Suicide Attacks in Pakistan, 2006–2010

Source: Worldwide Incidents Tracking System, National Counterterrorism Center, wits.nctc.gov (accessed November 24, 2009; April 1, 2010; and April 1, 2011).

On December 11, 2007, Rabah Bechla, a sixty-three-year-old grandfather of seven, rammed a white van laden with explosives into the United Nations’ offices in Algiers and detonated it, destroying much of the building. Algerian officials put the death toll from the attack at forty-one, but emergency personnel on the scene said that it was much higher, perhaps as many as sixty. At approximately the same time, another suicide attacker, a thirty-year-old man named Larbi Charef, targeted Algeria’s constitutional council. A passing bus full of students absorbed much of the blast, which killed and wounded many of them. The two attacks were brutal and stunning, all the more so because a grandfather of seven hardly fit the profile of the typical suicide attacker, prompting a local journalist to comment, “If a grandfather can blow himself up, anyone can.”36

The Algerian civil war of the 1990s resulted in the deaths of perhaps 100,000 people.37 During the conflict, the most radical members of the various armed resistance groups were Algerians who had returned from fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan. They were a relatively small percentage of the overall opposition, but because of their experience and determination, they became a decisive element, pushing it toward a radical rejection of democracy in favor of the violent establishment of a conservative form of a religiously governed state.38 During this time they maintained contact with Osama bin Laden and the al Qaeda network through personal connections forged during their time in Afghanistan. By the later 1990s, this faction of the resistance called itself the Salafi Group for Preaching and Combat (Groupe Salafiste pour la Predication et le Combat, GSPC).39 The violence of the group, which included massacres of civilians, led to its isolation as the government of Algeria ended the civil war by co-opting moderate factions through a program of amnesty and reconciliation.

In 2004, needing money, recruits, and legitimacy, the GSPC reached out to al Qaeda through Zarqawi’s Iraqi franchise. By 2006 it had become part of the al Qaeda network, renaming itself al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and began to reinvent itself as a part of the global struggle for Islam.40 The al Qaeda brand brought with it respect and legitimacy among militant circles, allowing the group to retain local members who otherwise would have traveled to Iraq to wage jihad; this in turn allowed the group to attack the Algerian government much more systematically. The organization even began to run training camps for militants from neighboring Morocco and Tunisia.

The use of suicide attackers in Algeria demonstrated the GSPC’s transformation into an al Qaeda franchise. As early as 2004 Algerian recruits in Iraq had begun making martyrdom videos prior to suicide attacks against U.S. targets and by 2005 had become a significant percentage of the foreign fighters wreaking havoc in Iraq.41 The introduction of suicide bombing into Algeria therefore did not necessitate any new organizational developments, cultural conditioning, or training, but instead a diversion of recruits and resources from one theater to another. The first suicide attack to occur in Algeria took place on April 11, 2007, killing thirty-three people.42 An attack on August 19, 2008, killed forty-three people at a police college, forty-one of whom were civilians according to authorities.43

As was the case with Zarqawi’s attacks in Iraq, the suicide missions carried out by al Qaeda’s Algerian franchise were not welcomed by the Algerian people, including local Islamic scholars, who criticized them. That they continued to be conducted suggests that the Algerian people were not the audience at which the attacks were aimed. Rather, high-visibility operations were carried out to get publicity for the global movement when its fortunes were waning as a consequence of its decline in Iraq.44 Its isolation from the local context has prevented AQIM from building a self-reinforcing relationship with the local populace. The group carried out fewer attacks in 2008 than in 2007, but the number of suicide missions it conducted increased. In contrast, the group was responsible for only one suicide attack in 2009 and one in 2010.45

Somalia is one of the countries recently afflicted by suicide bombing. Years without effective centralized government have left the country vulnerable to foreign invasion, poor, devastated, and ravaged by criminal gangs and warlords. Nevertheless, through all the years of lawlessness and corruption, there were no suicide attacks until 2006. That September, suicide bombers attempted unsuccessfully to kill the interim president. The following November, three suicide bombers killed two police officers.46 These attacks were initially blamed on al Qaeda, which has long had a presence in East Africa, but by 2008 were attributed to a new, indigenous group, Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen (Movement of Warrior-Youth), or simply al-Shabab (which means “youth”). As of late 2010 al-Shabab occupied a middle ground between its emergence as a local group and its ambitions to join the global jihadi movement. Although it publicly and repeatedly pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden’s movement, bin Laden never formally recognized the group as an al Qaeda affiliate.47

In October 2008 five bombers simultaneously attacked Somali government and UN sites in northern Somalia, killing twenty-one people. The following February suicide bombers killed eleven African Union peacekeepers in Mogadishu. In May a bomb being prepared for a suicide attack detonated prematurely, killing several members of al-Shabab. The next month a suicide attack carried out by three men in a Toyota truck killed twenty people, among them the minister of security, Col. Umar Hashi Adan. On September 17, 2009, two suicide bombers again attacked peacekeeping forces of the African Union, killing seventeen. Al-Shabab claimed all these attacks.48 An operation in Mogadishu on December 3 killed nineteen people, of whom three were government ministers. On July 11, 2010, the group signaled an intensification of its campaign by carrying out simultaneous suicide bombings in Kampala, the capital of Uganda, killing seventy-six people.49

Of the many recent suicide bombings, the assault of October 2008 has generated the most significant concern among security analysts, primarily because of the identity of one of the suicide attackers. Twenty-six-year-old Shirwa Ahmed was born in Somalia but had lived most of his life in Minnesota and was the first American citizen to carry out a suicide attack. Ahmed was one of a small number of Somali Americans from Minnesota who had journeyed to Somalia to fight on behalf of al-Shabab. These men were undoubtedly influenced by al-Shabab’s propaganda videos, which are available online.50 Much of their radicalization, however, seems to have stemmed not from jihadi propaganda, but from their inability to assimilate fully into American society. Ahmed and his fellow travelers came from a socially isolated minority in which broken families were common and discrimination of varying sorts a regular occurrence. Lacking a sense of familial or national belonging, many of these young men sought refuge in Somali American gangs. By that point, much of the process of radicalization had already been completed, and it was up to al-Shabab to give shape to the somewhat incoherent frustrations of these men by indoctrinating them into the world of jihad and martyrdom. As of October 2009, a total of six Somali Americans had died fighting for al-Shabab.51

Although suicide bombing on the global level intensified in the years after the 9/11 attacks, the reach of the radicals seemed to be limited, with no major operations in Europe or the United States for several years. On July 7, 2005, however, the jihadi movement seemingly demonstrated a long geographical reach when three suicide attackers blew themselves up on different trains in the London subway system; a fourth bomber, who was delayed by a glitch in his bomb, chose to detonate himself and his weapon on a bus since the subway had been closed in the aftermath of the first three attacks.52 The weapons, as in previous instances of locally initiated terrorist attacks, were relatively unsophisticated homemade explosives carried in backpacks. The attacks killed fifty-two people and became a major news story on both sides of the Atlantic because of the closeness of the United States and the United Kingdom, the shared language, and the nationality of the attackers, all four of whom were British citizens.

Three of the bombers were of Pakistani descent, and the fourth was a naturalized immigrant from Jamaica. The United Kingdom has a large community of Pakistani immigrants and their second and third generation descendents. Many émigrés have sought to preserve their cultural traditions and sense of communal identity, sometimes leaving their children conflicted in terms of their individual identities because they cannot identify fully with either the land of their birth or the land of their parents’ identity.53 Over the years, some radical young Muslims, many from the Pakistani community, have taken advantage of permissive British policies regarding freedom of speech and expression to agitate openly against the state.54 By the start of the new millennium, British counterterrorism officials were regularly investigating plots initiated by radicals residing in the United Kingdom. In 2004 months of investigation led to Operation Crevice, during which seven hundred police officers raided nearly two dozen locations and broke up an al-Qaeda-directed terrorist cell.55

Operation Crevice missed the 7/7 plotters because they had only minimal connections to known jihadi figures. Despite suspicions that the attack must have been planned and directed by someone with more experience in such matters and with closer connections to the global jihadi leadership than the bombers had, no such mastermind or fifth bomber appears to have been involved. Instead, the London bombers “were essentially an autonomous clique whose motivations, cohesiveness, and ideological grooming occurred in the absence of any organized network or formal entry into the jihad.”56 More striking perhaps is that in this cell there was apparently little division of labor or differentiation of roles. The four members helped to radicalize each other in a process of mutual feedback. All four seem to have participated in target selection and contributed to building the bombs.

The attackers did, however, receive technical assistance from al Qaeda’s established leadership. In late 2004 two of the London bombers traveled to Pakistan and received training in the production and use of homemade explosives as well as ideological encouragement. From that point on, the cell remained in contact with radicals in Pakistan and in the United Kingdom.57 Attacks carried out without such technical assistance—such as attempted copycat bombings in London on July 21, 2005, and suicide bombings in Glasgow in July 2007—have been far more amateurish. Individual initiative on the part of the London bombers and direction from established jihadis were necessary components of the July 7 bombings.

Reconciling the roles of individual and organizational control within small jihadi groups, particularly those using suicide attacks, has proven to be problematic to this point. Bruce Hoffman notes, for example, that outside technical advice is necessary to provide inexperienced groups with the skills necessary to carry out even relatively simple attacks, such as the July 7 bombings. Centralized leadership is required for inspiring prospective groups and members, organizing their behavior, and especially for managing the publicity generated by their attacks. For instance, Siddique Khan and Shahzad Tanweer, the two July 7 bombers who traveled to Pakistan, recorded martyrdom videos that were subsequently used by the al Qaeda leadership to claim responsibility for the attack. Al Qaeda’s media branch edited Tanweer’s video so that his testimonial was framed by messages from Ayman al-Zawahiri and released that version on the first anniversary of the attack.58 Whatever the actual motivations of the London bombers in life, their deaths were used by al Qaeda’s martyrologists as evidence of the organization’s ongoing relevance and power. Hoffman thus emphasizes the importance of organizational leadership, and of the established al Qaeda leadership in particular, for the global jihadi movement.

In contrast, Marc Sageman argues that the seemingly coherent behavior of the global jihadi movement results from the interactions of social networks formed by peer groups of like-minded, alienated young men. His analysis, based on extensive fieldwork and interviews with jihadis and would-be jihadis, suggests that local, personal motivations are much more significant in global jihadism than are centralized organizational control and ideology. Social and political conditions marginalize individuals, who then form close groups, or cliques, based on kinship and friendship. Membership in these small, insular groups intensifies and politicizes preexisting grievances, making the group more susceptible to the jihadi message. These small groups and the loose networks that they form initiate attacks opportunistically within the overall ideological framework of global jihadism and therefore serve to advance the jihadi agenda in the absence of centralized leadership.59

These two approaches to the role of organizational leadership are seemingly quite different from one another and have been at the heart of an unusually sharp public debate between Hoffman and Sageman. The two positions, however, are not as far apart as they might seem; they can both be readily accommodated within this book’s analytical framework. As already shown, motivations vary at different levels of the suicide-bombing complex. It is not surprising that jihadi suicide bombers demonstrate intensely personal motivations and that they might differ from the ideological agendas of the leaders that inspire them. Hoffman and Sageman tend to frame their analyses in terms of leadership, so what they are examining are ultimately patterns of organizational control. From this perspective, both their leadership models have something to offer, for the form of control that characterizes the jihadi movement—and ultimately makes its manufacture of suicide bombers possible—is an interesting mixture, in which bottom-up control is tempered with top-down direction accounting for the loose but coherent nature of jihadism.

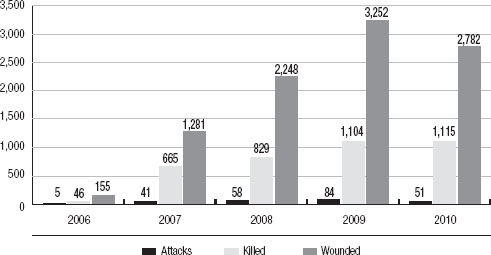

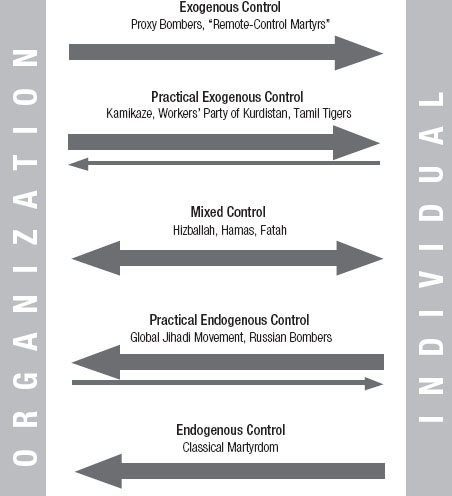

One of the most important changes in suicide bombing in recent years has been the replacement of centralized organizational control—such as that which characterized Hizballah’s early attacks, the trial runs of the IRA and the PKK, and the LTTE’s suicide-bombing complex—with much more fluid, decentralized control, such as that characteristic of the suicide bombing of the second intifada and of the global jihadi movement.60 Control in this context does not imply brainwashing or domination; rather, excessive direction on the part of the sponsoring organization would rob bombers of the ability to think and decide, which is part of what makes them so dangerous. Centralized control is also inconsistent with the empirical evidence regarding self-motivated would-be martyrs who have flocked to al Qaeda’s various franchises seeking the opportunity to kill themselves. Understanding how groups weak in formal organizational structures exert such seemingly extraordinary control over some of their followers is essential in explaining the spread and diversification of suicide bombing.

Control can be spread out along a spectrum of possibilities, ranging from domination to suggestion. The endpoints of the spectrum represent two different approaches to the problem of control, which consist of intelligent and unintelligent control, as characterized by Lao Tzu, the founder of Taoism. Lao Tzu believed that intelligent control meant convincing someone to want to do what you want them to do, that is, persuasion rather than domination. Such control is intelligent because from the perspective of the individual controlled, it appears to be freedom. Unintelligent control, on the other hand, consists of forcing an individual to perform a task against his or her will, usually under threat of punishment. Unintelligent control is therefore perceived as external domination and thus is often resented.61

What Lao Tzu called unintelligent control is more formally referred to as exogenous control, which is “a condition imposed from without and involves a specific, centralized control structure, as well as distinct roles for the controller and controlled, and information flows vertically.” Since exogenous control demands a centralized structure, it is best suited to traditional bureaucratic organizations with hierarchical structures. In contrast, intelligent control is known as endogenous control. Endogenous control is characterized by negotiation and a lack of formal organizational roles or hierarchies (that is, controller and controlled feel themselves to be fundamentally the same). It is spread among individuals instead of being concentrated in any one center.62 Endogenous control, with its distributed control process, works best in an egalitarian, networked environment with reciprocal flows of information. In the context of suicide bombing, endogenous control makes use of deeply felt bonds to friends and family to convince the individual to sacrifice his or her life for the benefit of the group. It is the difference between having volunteers for suicide missions and having to force individuals to undertake suicide missions against their will. Only organizations with exceptional power and discipline can maintain the latter for an extended period of time.

The government of Imperial Japan during World War II was strong enough to rely heavily on “unintelligent” control. The men who became Kamikaze pilots had very little power or authority relative to the state. They knew that they were going to their deaths and had tactical control over their own missions, but they did not have the power to reject the role handed to them by the government. They were compelled to obey, or at least to demonstrate the outward signs of obedience, even if internally they rationalized their own deaths in a completely different manner. The Tamil Tigers provide another example of an organization that deployed suicide attackers using primarily exogenous control mechanisms. The leadership of the LTTE, Vellupillai Prabhakaran in particular, maintained centralized control over the entire process, from recruitment, to training, to mission operations, and memorializing the dead after the fact. Although individual Black Tigers were fully complicit in this process, their enthusiasm and obedience did nothing to change the fact that their lives were Prabhakaran’s to use as he saw fit.

In the model of technology practice, a mutual relationship exists in which the technical element and the organizational element influence each other. Since suicide bombing utilizes human beings as part of its technical element, this relationship has been explored here in terms of management. The managerial relationship between organizations and their human bombers has been represented graphically by a two-way arrow to indicate that communications between the two are mutual, but there are many ways for this relationship to express itself.

Describing an organization as utilizing exogenous control does not necessarily mean that the arrow must point in only one direction, from the organization to the individual. Such extreme forms of coercive control have been used in the manufacture of suicide bombers, but they have been extraordinarily inefficient because the responsible organization is seen as being manipulative and therefore cannot make use of the legitimizing power that comes from having followers willing to die for the cause. The Provisional IRA’s proxy bombers and the various cases in which individuals have been unwittingly used as remote-control martyrs fall into this category. In the opposite category, pure endogenous control, all decision making is by the individual. Classical martyrdom falls into this category because the decision to die is motivated by an authentic commitment to a cause or group but is far too unpredictable to be used at the tactical level. Individual suicide falls outside this spectrum since it is perceived to be selfish and does not contribute to organizational power on either the tactical or the strategic levels.

The most effective users of suicide attackers combine elements of endogenous and exogenous control, but often one pathway or the other dominates. In the case of practical exogenous control, like that which characterized Imperial Japan and the Tamil Tigers, the path from organization to individual dominates, with the organization taking the initiative and setting requirements and leaving the individual a narrow range of action within which to fulfill his or her obligations. In a more endogenous structure, such as global jihadism, the individual has freedom to initiate action, and the power of the organization to coerce or intimidate its followers is reduced. These structures can be understood schematically as illustrated in Figure 8.3.

Patterns of control have their limits. Groups in the middle of the spectrum, like Hamas and Hizballah, which balance endogenous and exogenous control, have found their ability to make and use suicide attackers to be severely constrained by what their communities are and are not willing to condone.

Practical exogenous control structures depend upon power expressed through clearly defined channels making them vulnerable to disruption. After the surrender of Imperial Japan, there were no more Kamikaze attacks against U.S. forces (and the occupation as a whole was surprisingly nonviolent in contrast to the brutality of the fighting in the Pacific).63 Similarly, for two years after the defeat of the LTTE and the death of Vellupillai Prabhakaran, there were no suicide attacks by former members of the Tamil Tigers. In both cases, the ability to make and use suicide attackers ended when the group’s leadership was defeated.

Practical endogenous control structures, in contrast, are resistant to such “decapitation,” so the jihadi movement continues to survive despite the loss of much of its leadership. Because the movement depends upon trust and ideological homogeneity among members, however, it cannot mobilize entire societies and become a mass movement. Organizations lacking formal structures depend on a high degree of trust among members, which in turn pushes these organizations toward being relatively small in size and uniform in mindset and ideology.64 Leaders need then only provide symbols, narratives, and rituals consistent with the expectations of their followers in order to achieve the power to influence, but not to command, the behavior of their followers.65

FIGURE 8.3Forms of Organizational Control

Source: Jeffrey W. Lewis, 2011.

The precise mechanisms by which endogenous forms of control function have been understood only for a few decades. In the 1970s and 1980s, computer modeling of naturally occurring chemical and biological systems demonstrated that organized group behavior need not be centrally controlled but instead can emerge collectively from the behavior of a system’s individual constituents.66 That is to say, relatively simple rules can produce complex, goal-oriented behavior even when the path toward a given goal is not explicitly articulated in the rules themselves. Each autonomous actor within the system adheres to the same set of rules, and from these interactions a collective pattern of behavior emerges giving the system as a whole coherence that is not readily discernable at the level of the individual actors.67

It is now clear that this dynamic applies to human organizations. Loosely organized networks can produce coherent group behavior even in the absence of any bureaucratic or hierarchical control structure.68 Individual motivations and small-group dynamics create a potential set of actors, and ideological leadership provides a set of cues to direct their behavior. This is why the models of organizational leadership suggested by Hoffman and Sageman can, indeed do, coexist comfortably with one another; the global jihadi leadership provides the rules for behavior of the movement, but within the framework established by these rules individual jihadis have considerable autonomy.

Bin Laden and Zawahiri encouraged such a leadership model to promote terrorism from the grass roots up throughout the Western world. Zawahiri, in Knights under the Prophet’s Banner, emphasizes that responsibility falls on the shoulders of individual Muslims, who are obligated to carry on jihad even in the absence of direct orders from the global leadership. The role of the leadership is to inspire young men by making them aware of their obligations to the faith and setting an example for them to follow.69 In December 2002 Zawahiri distributed a pamphlet, “Loyalty and Separation,” in the Arabic-language daily al-Quds al-Arabi (London), in which he wrote, “Young Muslims need not wait for anyone’s permission, because jihad against the Americans, the Jews, and their allies, hypocrites and apostates, is now an individual duty, as we have demonstrated.”70

Perhaps more influential in the development of al Qaeda’s global strategy has been Abu Musab al-Suri, who articulated a plan for directing a diffuse, goal-oriented global movement in The Global Islamic Resistance Call, a 1,600-page document published online in 2005.71 For Suri, the global Islamic resistance is an idea or a system rather than an organization. The purpose of this system is to transform disaffected individuals into a coherent force by providing inspiration and direction in order to align individual goals with those of the group. Suri appears to have a strong understanding of what makes endogenous control work, for his book sees the global jihad as a communicative instead of an organizational phenomenon. According to Suri, “There are no organizational bonds of any kind between the members of the Global Islamic Resistance Units, except the bonds of a ‘program of beliefs, a system of action, a common name, and a common goal.’ “72

The global program imagined by Suri has become a possibility due to the dramatic changes in electronic communication over the past two decades. Terrorism has always been a form of communication dependent upon media attention. Traditionally the mainstream media—first the mass print media of the late 1800s and then the electronic mass media of the post–World War II years—played the biggest role in communicating violent extremists’ messages to the masses. Even in instances in which extremist groups did not attempt to claim or manage the consequences of their acts, the media communicated them powerfully.73 The recent expansion of satellite television into areas previously dominated by state-run media, particularly countries in the Arab world, has meant that more and more people are involved in the public sphere, which has given them access to the messages of extremists (as well as others).74

Nevertheless, television and the print media, staples of the “old media,” were always inherently limited in how they could directly benefit radical groups. Managers at the stations, not the radicals, choose what to air, and viewers received this information only passively, limiting their involvement. The migration of communication to the Internet has helped extremist groups overcome these limitations, because the web allows virtually anyone to become a “broadcaster” by posting video clips and enables secure, two-way communication even at great distances.

In recent years, the scope of Internet use by extremists has become staggering. Gabriel Weimann tracked no fewer than 4,300 websites serving listed terrorist groups between 1998 and 2005.75 The most important element of the Internet, as opposed to other forms of electronic communication, is its capacity for two-way exchanges. Participation by individuals in online chat groups, for example, is an active process that links individuals to a larger group of like-minded colleagues irrespective of distance.76 Experienced militants are able to communicate directly with potential recruits and to use video propaganda to push them toward action. Even before 9/11, there was a global pool of potential recruits in the form of young Muslim men who felt alienated from their cultures and societies in largely Muslim states as well as in Europe and elsewhere. These men formed isolated subcultures or islands of identity, with a few being able or willing to take the dramatic step of traveling to a place like Afghanistan to forge formal links with the global jihadi leadership. The Internet has proven to be ideal for bringing together the pieces of this fragmented global community, and one result is the cyber-mobilization of dissatisfied young men, many of whom were already on the margins of society, around the world.77

The majority of young men who become attracted to jihadism as an online social movement will never become suicide attackers or do anything that directly supports the movement’s global military campaign. Jarret Brachman calls this group of interested but non-committed men “jihobbyists.” They are enthusiasts of the global jihadi movement, but their interest will never get to the point of formally joining the movement. Instead they support jihad from the comfort of their homes by hosting websites, editing videos, or compiling audio files of speeches by well-known al Qaeda members.78 Only a few of these jihobbyists will go to the next level and actually take part in the social activities with other members, a step away from cheerleading and toward action that Brachman calls preparatory jihad. In general, the large number of jihobbyists makes the movement a genuine social phenomenon for disaffected young men around the world.

The cyber-mobilization of potential jihadis demonstrates the power of the Internet simultaneously to unify and fragment human communities, for the creation of this virtual community has come at the expense of real human communities. Critics of the Internet have long recognized that the sheer diversity of people and information available online sometimes leads not to mutual understanding or broader awareness of cultural differences, but instead to fragmentation into relatively homogeneous sub-communities since individuals are able to seek those of a like mind online and avoid those with whom they disagree. In the mid-1990s Stephen Talbott observed, “In any event, one of the Net’s attractions is avowedly its natural susceptibility to being shivered into innumerable, separate, relatively homogeneous groups. The fact that you can find a forum for virtually any topic you might be interested in, however obscure, implies fragmentation as its reverse side.”79

The Internet has the capacity to exacerbate general tendencies that characterize human social networks. Since social networks provide a sense of belonging and approval, people tend to form social relationships with those of like mind and to distance themselves from those who think differently. Social networks are therefore the consequence of a process of self-selection and are inherently self-intensifying by their nature. As the authors of a recent study on social networks note, “When people with ideological or class-based interests are not surrounded by like-minded individuals in their physical neighborhoods, they tend to withdraw and form relationships outside those environments.”80 The Internet of course intensifies this process by breaking down physical distances and allowing for the creation of communities of geographically dispersed individuals.

Because the Internet facilitates disengagement from person-to-person interactions in favor of a virtual community of like-minded colleagues, it can facilitate detachment from reality. Potential jihadis are especially susceptible to this lure because they have already, by their own inclination, entered into the imagined world of religious fundamentalism and have likely detached themselves from real social relationships.81 Unlike other online communities, however, potential jihadis have the opportunity to make bloody fantasies a reality through participation in jihad. The possibility of turning the online world into a reality—into a human community defined by the values of struggle and self-sacrifice in which the social outcast has the ability to become the most revered figure, the martyr—has proven to be an irresistible lure to some.82

The power to use the Internet for facilitating extremist violence should not be overstated. In the world of terrorism, distance-learning is no substitute for contact, training, and apprenticeship, so the Internet will be a dangerous tool for jihadis only so long as it facilitates real world interactions between new recruits and experienced fighters. The technical capabilities of online terrorists will always be rudimentary since most are by definition new to militancy and must seek knowledge regarding weapons manufacture and use. The Internet has become the de facto source of information for beginning jihadis, and here its impact has also been mixed. Much of the self-published online material regarding weapons manufacture is inaccurate.83 Mastering even relatively simple technologies, such as bomb making, are best achieved via hands-on experience. The failures of poorly trained and inexperienced potential terrorists, for example, the “shoe bomber” Richard Reid and the two men who attempted to bomb Glasgow airport in 2007, testify to the technical challenges of even “simple” suicide bombing plots and lend credence to Michael Kenney’s observation that “militants ultimately learn terrorism by doing terrorism.”84

Analysts have long recognized that such radical groups as al Qaeda are capable of effectively blending aspects of religious war and modern global business. This fusion, after all, was the reason Peter Bergen called his pioneering study of al Qaeda Holy War Inc. Christoph Reuter has rightly noted that suicide bombing itself is just such a strange hybrid, a mix of old and new: “Notwithstanding the pretense of traditional religion in which their actions are typically cloaked, suicide bombers are quintessentially modern, in that they have left behind the traditional interpretations of religion in order to exploit only selected aspects of religion. They are a mixture of the Battle of Karbala and cable television—old myths and new media.”85 In recent years, as al Qaeda has become a social movement as opposed to a bureaucratic organization, scholars have begun to use a new business model, that of international brand marketing, to provide an analytical framework.86

Marketing has always been a control system for businesses, allowing them to create demand for products in order to manage markets and make them more predictable.87 This management takes the form of the systematic manipulation of anxieties in the target audience in order to encourage members of the audience to see a particular product as the answer to deep-seated needs. Brands and trademarks are important tools in this process of manipulation. Market saturation leads to the emergence of brands as a way of differentiating products in a crowded marketplace and allows for an ongoing measure of control by creating a relationship of trust between consumer and brand name that transcends the mere utilitarian purpose the product was meant to serve.88

Global marketing in recent years has taken this basic idea—developing an emotional connection between consumer and brand name—to extremes, and certain brands have become icons in global spaces, addressing anxieties and desires in their target audiences far beyond the effective range of the product or service. Such “iconic” brands perform these emotional tasks because the brand has become more a symbol of a particular lifestyle or identity than an actual good or product. Douglas Holt has shown that modern global brands are marketed as stories or identity myths so that they resonate with the insecurities of their consumers. He wrote, “Brands become iconic when they perform identity myths: simple fictions that address cultural anxieties from afar, from imaginary worlds rather than from the worlds that consumers regularly encounter in their everyday lives. The aspirations expressed in these myths are an imaginative, rather than literal, expression of the audience’s aspired identity.”89 For consumers, Holt concludes that “The greatest opportunity for brands today is to deliver not entertainment, but rather myths that their customers can use to manage the exigencies of a world that increasingly threatens their identities.”90

From such a perspective al Qaeda has indeed become the most recognizable brand in the business of jihadi resistance. The service it provides is martyrdom; the product emerging from the interaction of firm and customer is today’s globalized martyr. Recall that the difference between suicide and martyrdom is distinguishable only by the intent of the individual. Confirmation of individual intent only becomes generally accepted within the community when it is affirmed organizationally, so al Qaeda truly does perform a service when it claims martyrs and validates their sacrifices. These martyrs in turn confirm the legitimacy of the brand, making the process a self-perpetuating, closed loop. Take, for example, the case of a man who took part in the May 12, 2003, attacks in Riyadh.

Khalid al-Juhani was a veteran of the global jihadi movement, having joined it as a fighter in Bosnia in 1992. He became an al Qaeda member and recorded a martyrdom video in Afghanistan in 2001, a full two years before the attack in which he would take his own life.91 This lengthy time lag between taping and the operation suggests a shift in purpose for the video testaments within the global jihadi movement. It was still a contract, publicly stating the intentions of the individual and binding him to the movement, but it had also become something more. Unlike many other martyrdom videos connected to local suicide bombing in the 1990s, this one was not recorded immediately before a specific attack for the purpose of ensuring the reliability of the recruit. Rather, it was an affirmation of identity on the part of Khalid, that is, a statement of his desire to sacrifice his life for the movement. The exact time and place of his attack, and death, did apparently not matter to him or to the organization. Instead, the significance for the individual derived from the confirmation of identity through his assertion of group affiliation; in turn, the organization stood to have its legitimacy enhanced by having yet another young man pledge his loyalty, unto death, to the movement.

In 1957 Vance Packard published a critical analysis of the American advertising industry’s efforts to utilize insights from the social and behavioral sciences to control the minds of consumers, or in his words, to “engineer” their consent. In particular, he identified eight “hidden needs”—anxieties that were particularly susceptible to outside manipulation—that markers targeted. The identity myths of iconic brands are successful because they satisfy several of these needs simultaneously. In analyzing al Qaeda as an iconic brand that perpetuates itself via myth, one would find that its identity myth satisfies six of Packard’s eight hidden needs by selling emotional security, reassurance of worth, ego-gratification, a sense of power, a sense of roots, and most tellingly, selling a sense of immortality.92

There is a paradox at the heart of the global jihadi use of suicide attackers. The movement as a whole is opposed to the modern, secular world and seeks to combat modernity by placing faith and community foremost. The jihadis are doing so, however, by using the technologies and organizational structures of the modern world.93 Use of electronic communications technologies, business strategies, and of course weapons can be excused on the basis of pragmatism; effectiveness dictates using the tools of modernity to undo modernity. Development and use of the suicide attacker, a weapon not regularly used by states since 1945, cannot be explained away so easily.

Suicide bombers are at the heart of the public image of the global jihadi movement because they are understood to embody the essence of the conflict. Assaf Moghadam suggests, “Jihad and martyrdom are . . . presented as the very antithesis of everything that the West stands for.”94 Jihadi suicide bombers, however, are as modern a weapon as one can imagine. Although their ostensible purpose is defending faith and community, they are strikingly individualistic; one recent analysis describes the movement as a whole as being characterized by “individualism bordering on anarchism.”95 Jihadi leaders encourage this individualism by undermining traditional religious authorities, established political parties, and even family relationships. In doing so, they seek to break the bonds that connect potential followers to their communities and might stand in the way of their participation in jihad. Instead of serving their communities, potential jihadis are encouraged to abandon them in order to receive individual rewards in heaven.96

Jihadi leaders endeavor to fragment communities by isolating individuals, instilling in them a deep sense of anxiety, and then marketing an alternative form of identity in order to alleviate this anxiety. Of note, members of the senior leadership of the jihadi movement have to this point shown little willingness to become martyrs themselves. This suggests that they understand suicide attackers as tools to be used rather than heroes that they would emulate themselves.

In the indiscriminate suicide bombing unleashed by the global jihadi movement, people have become material, social ties have been devalued, and sacred relationships have become transactions, a situation that critics of modern technology from Marx to Heidegger would have recognized and condemned. Thus the jihadi appropriation of modern technology extends beyond the use of the tools of the modern world to combat modernity; the jihadi mindset has become a caricature of the modern world as well. This paradox, perhaps more than any other factor, explains the limited appeal of the global jihadi movement even after thousands of “inspirational” suicide attacks.

After more than a decade of suicide missions, the elusive goal of suicide bombing’s most enthusiastic users—restoration of Islamic governance in the form of a new caliphate unifying the world’s Muslims—is no closer. Instead of marking progress toward the goal, the attacks that the movement has mustered have tended to serve shorter-term goals, such as publicizing the movement, allowing it to lay claim to defending the Islamic community, and attracting new recruits.

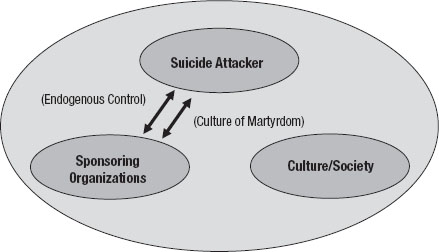

This emphasis on short-term rather than long-term goals has alienated the jihadis from nearly all sources of social support. In terms of the model of technology practice developed earlier in this work, the technical and organizational elements of technology practice have been decoupled from the social/cultural element. Communities see little need for suicide attackers, and consequently most societies have ceased to share the jihadis’ acceptance of a culture of martyrdom. Therefore, instead of a triangle of mutually reinforcing relationships, the model of suicide bombing that best illustrates the decentralized suicide bombing of “self-starters” and other loosely affiliated jihadi groups is one of a bilateral relationship that still produces feedback and radicalization, but does so in relative social isolation. There remains an endogenous managerial relationship between organizations and bombers and a shared reverence for martyrdom that makes the creation of suicide bombers possible, but without the link to a broader constituency, there is little popular demand for jihadi suicide attacks (see Figure 8.4).

FIGURE 8.4Jihadi Suicide Bombing

Source: Adapted from Arnold Pacey, The Culture of Technology (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1983), 6.

This situation is analogous to that of Imperial Russia, except that whereas the Russian anarchists lacked the organizational infrastructure necessary to sustain a campaign of suicide bombing, the global jihadis lack the social connections necessary to consolidate their attacks politically. Their use and overuse of suicide bombing has become an incomplete, ineffective form of technology practice, more like sequential mass suicide than the use of self-sacrifice for an achievable political goal. The result has been the broad but shallow globalized suicide bombing of the first decade of the new millennium.