Figure 25: Yesterday, what did John give to Mary in the library?

Speech is a non-instinctive, acquired, ‘cultural’ function.

Edward Sapir

SOMEONE MIGHT ASK this in English: ‘Yesterday, what did John give to Mary in the library?’ And someone else might answer, ‘Catcher in the Rye.’

This is a complete conversation. Not a particularly fecund one, but, still, typical of the exchanges that people depend on in their day-to-day lives, representative of the way that brains are supersized by culture as well as the role of language in expanding knowledge from the brain of a single individual to the shared knowledge of all the individuals of a society, of all the individuals alive, in fact. Even of all the individuals who have ever lived and written or been written about. It wasn’t the computer that ushered in the information age, it was language. The information age began nearly 2 million years ago. Homo sapiens have just tweaked it a bit.

Discourse and conversation are the apex of language. In what way, though, is this apical position revealed in the sentences in the discourse above? When native speakers of English hear the first sentence of our conversation in a natural context, they understand it. They are able to do this because they have learned to listen to all the parts of this complex whole and to use each part to help them understand what the speaker intends when they ask, ‘Yesterday, what did John give to Mary in the library?’

First, they understand the words, ‘library’, ‘in’, ‘did’, ‘John,’ and the rest. Second, all English speakers will hear the word with the greatest amplitude or loudness and also notice which words receive the highest and lowest pitches. The loudness and pitch can vary according to what the speaker is trying to communicate. They aren’t always the same, not even for the same sentence. Figure 25 shows one way to assign pitch and loudness to our sentence.*

Figure 25: Yesterday, what did John give to Mary in the library?

The line above the words shows the melody, the relative pitches, over the entire sentence. The italicised ‘yesterday’ indicates that it is the second-loudest word in the sentence. The small caps of ‘John’ mean that that is the loudest word in the sentence. ‘Yesterday’ and ‘John’ are selected by the speaker to indicate that they warrant the hearer’s particular attention. The melody indicates that this is a question, but it also picks out the four words ‘yesterday’, ‘John’, ‘Mary’ and ‘library’ for higher pitches, indicating that they represent different kinds of information needed to process the request.

The loudness and pitch of ‘yesterday’ says this – one is talking about what someone gave to someone yesterday, not today, not another day. This helps the hearer avoid confusion. The word ‘yesterday’ doesn’t communicate this information by itself. The word is aided by pitch and loudness, which highlight its specialness for both the information being communicated and the information being requested. ‘John’ is the loudest word because it is particularly important to the speaker for the hearer to tell him what ‘John’ did. Maybe Mary is a librarian. People give her books all day, every day. Then what is being asked is not about what Suzy gave her but only what John gave her. The pitch and loudness let the hearer know this so that they do not have to sort through all the people who gave Mary things yesterday. The word ‘John’ already makes this clear. The pitch and loudness highlight this. They offer additional cues to the hearer to guide their mental search for the right information.

Now, when someone asks this question, what does the asker look like? Probably they look something like this: the upper arms are held against their sides, with their forearms extended, palms facing outward and their brow furrowed. These body and hand expressions are important. The hearer uses these gestural, facial and other body cues to know immediately that you are not making a statement. A question is being asked.

Now consider the words themselves. The word ‘yesterday’ appears at the far left of the sentence. In the sentence below the <>’s indicate the other places that ‘yesterday’ could appear in the sentence:

<> what <> did John <> give <> to Mary <> in the library <>?

So we could ask:

‘What did John give yesterday to Mary in the library?’

‘Yesterday what did John give to Mary in the library?’

‘What did John, yesterday, give to Mary in the library?’

‘What did John give to Mary yesterday in the library?’

‘What did John give to Mary in the library yesterday?’

‘What, yesterday, did John give to Mary in the library?’

But a native speaker is less likely to ask the question like this:

*‘What did yesterday John give to Mary in the library?’

*‘What did John give to yesterday Mary in the library?’

*‘What did John give to Mary in yesterday the library?’

*‘What did John give to Mary in the yesterday library?’

The asterisk in the examples just above means that one is perhaps less likely to hear these sentences other than in a very specific context, if at all. This exercise could be continued with other words or phrases of the sample sentence:

‘In the library, what did John give to Mary yesterday?’

This exercise on words and their orders need not be continued, however, since there is now enough information to know that putting together a sentence is not simply stringing words like beads on a cord.

Part of the organisation of the sentence is the grouping of words in most languages into phrases. These phrases should not be interrupted, which is why one cannot place yesterday after the word ‘in’ or after the word ‘the’. Grammatical phrases are forms of ‘chunking’ for short-term memory. They aid recall and interpretation.

Still, a great deal of cultural information is missing from the above example. For instance what in the hell is a library? Is John a man or a woman? Is Mary a man or a woman? Which library is being talked about? What kinds of things are most likely to be given by John? Do John and Mary know each other? Although there are a lot of questions, one quickly perceives the answers to them if they are the speaker or hearer in the above conversation because of the knowledge people absorb – often without instruction – from their surrounding society and culture. People use individual knowledge (such as which library is the most likely candidate) and cultural knowledge (such as what a library is) to narrow down their ‘solution space’ as hearers. They are not, therefore, obligated to sort through all possible information to understand and respond, but must only mentally scroll through the culturally and individually most pertinent information that might fit the question at hand. The syntax, word selection, intonation and amplitude are all designed to help understand what was just said.

But there’s more, such as certain kinds of information in the example here. There is shared information, signalled sometimes by words such as ‘the’ in the phrase ‘the library’. Because someone says ‘the library’ and not ‘a library’, they signal to the hearer that this is a library that both know – they share this knowledge – because of the context in which they are having this conversation. The request here is for new information, as signalled by the question-word ‘what’. This is information that the speaker does not have but expects the hearer to have. Sentences exist to facilitate information exchange between speakers. Grammar is simply a tool to facilitate that.

The question is also an intentional act – an action intended to elicit a particular kind of action from the hearer. The action desired here is ‘give me the information I wish or tell me where to get it’. Actions vary. Thus, if a king were to say, ‘Off with his head,’ the action desired would be a decapitation, if he were being literal. Literalness brings us to another twist on how sentences are uttered and understood – is the speaker being literal or ironic or figurative? Are they insane?

With language, speakers can recognise promises, declarations, indirect requests, direct requests, denunciations, legal impact (‘I now pronounce you man and wife’) and other culturally significant information points. No theory of language should neglect to tell us about the complexity of language and how its parts fit together – intonation, gestures, grammar, lexical choice, type of intention and the rest. And what does the hearer do in this river of signals and information? Does she sit and ponder for hours before giving an answer? No she understands all of this implicitly and instantly. These cues work together. Taken as one, they make the sentence easier to understand, not harder. And the evidence is that the single strongest force driving this instantaneous comprehension is information structure. What is new? What is shared? And this derives not merely from the literal meanings of the words but from that implicit cultural knowledge that I call dark matter.

Into the syntactic representation of a sentence, speakers intercalate gestures and intonation. They use these gestures as annotations to indicate the presence of implicit information from the culture and the personal experiences of the speaker and hearer. But something is always left out. The language never expresses everything. The culture fills in the details.

How did human languages go from simple symbols to this complex interaction between higher-level symbols, symbols within symbols, grammar, intonation, gesture and culture? And why does all of this vary so much from language to language and culture to culture? Using the same words in British English or Australian English or Indian English or American English will produce related but distinct presupposed knowledge, intonational patterns, gestures and facial expressions. Far from there being any ‘universal grammar’ of integrating the various aspects of a single utterance, each culture largely follows its own head.

There are universally shared aspects of language, of course. Every culture uses pitch, attaches gestures and orders words in some agreed-upon sequence. These are necessary limits and features of language because they reflect physical and mental limitations of the species. Maybe – and this is exciting to think about – some of this represents vestiges of the ways that Homo erectus talked. Maybe humans passed a lot of grammar down by example, from millennium to millennium as the species continued to evolve. It is possible that modern languages have maintained 2-million-year-old solutions to information transfer first invented by Homo erectus. This possibility cannot be dismissed.

Reviewing what we have learned about symbols, these are based on a simple principle – namely that an arbitrary form can represent a meaning. Each symbol also entails Peirce’s interpretant. Signs in all their forms are a first step towards another essential component of human language, the triple patterning of form and meaning via the addition of the interpretative aids of gestures and intonation. As symbols and the rest become more enculturated, they advance up the ladder from communication to language, to a distinction between the perspective of the outsider vs the perspective of the insider, what linguist Kenneth Pike referred to as the ‘etic’ (outsider viewpoint) and the ‘emic’ (insider viewpoint). Signs alone do not get us all the way to the etic and the emic. Culture is crucial all along the way.

The etic perspective is the perspective a tourist might have listening to a foreign language for the first time. ‘They talk too fast.’ ‘I don’t know how they understand one another with all those weird sounds.’ But as one learns to speak the language, the sounds become more familiar, the language doesn’t sound as though it is spoken all that rapidly after all, the language and its rules and pronunciation patterns become familiar. The learner has travelled from the etic perspective of the outsider to the emic perspective of the insider.

By associating meanings with forms to create symbols, the distinction between form and meaning is highlighted.† And because symbols are interpreted by members of a particular group, they lead to the insider interpretation vs the outsider interpretation. This is what makes languages understandable to native speakers, but difficult to learn for non-native speakers. The progression to language is just this: Indexes → Icons → (emic) Symbols + (emic) grammar, (emic) gestures and (emic) intonation.

Following symbols, another important invention for language is grammar. Structure is needed to make more complex utterances out of symbols. A set of organising principles is required. These enable us to form utterances efficiently and most in line with the cultural expectations of the hearers.

Grammars are organised in two ways at once – vertically, also known as paradigmatic organisation, and horizontally, referred to as syntagmatic organisation. These modes of organisation underlie all grammars, as was pointed out at the beginning of the twentieth century by Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. Both vertical and horizontal organisation of a grammar work together to facilitate communication by allowing more information to be packed into individual words and phrases of language than would be possible without them. These modes of organisation follow from the nature of symbols and the transmission of information.

If one has symbols and sounds then there is no huge mental leap required to put these in some linear order. Linguists call the placing together of meaningless sounds (‘phonemes’ is the name given to speech sounds) into meaningful words ‘duality of patterning’. For example the s, a and t of the word ‘sat’ are meaningless on their own. But assembled in this order, the word they form does have meaning. To form words, phonemes are taken from the list of a given language’s sounds and placed into ‘slots’ to form a word, as, again, in ‘sat’: sslot1aslot2tslot3.

And once this duality becomes conventionalised, agreed upon by the members of a culture, then it can be extended to combine meaningful items with meaningful items. From there, it is not a huge leap to use symbols for events and symbols for things together to make statements. Assume that one has a list of symbols. This is one aspect of the vertical or paradigmatic aspect of the grammar. Next there is an order to place these symbols in that a culture has agreed upon for the organisation of the symbols. So the task in forming a sentence or a phrase is to choose a symbol and place it in a slot, as is illustrated in Figure 26.

Figure 26: Extended duality of patterning – making a sentence

Knowing the grammar, which every speaker must, is just knowing the instructions for assembling the words into sentences. The simple grammar for this made-up language might just be: select one paradigmatic filler and place it in appropriate syntagmatic slot.

From the idea that there is an inventory of symbols to be placed in a specific order, not a huge jump cognitively, early humans would have been using the ideas of ‘slot’ and ‘filler’. These are the bases of all grammars.

All of this was first explained by linguist Charles Hockett in 1960.1 He called the combination of meaningless elements to make meaningful ones ‘duality of patterning’. And once a people have symbols plus duality of patterning, then they extend duality to get the syntagmatic and paradigmatic organisation in the chart above. This almost gets us to human language. Only two other things are necessary – gestures and intonation. These together give the full language – symbols plus gestures and intonation. Here, though, the focus is on duality of patterning. As people organise their symbols they naturally begin next to analyse their symbols into smaller units. Thus a word such as ‘cat’, a symbol, is organised horizontally, or syntagmatically, as a syllable, c-a-t. But with this organisation it also becomes clear that ‘cat’ is organised vertically at the same time. So one could substitute a ‘p’ for the ‘c’ of cat to produce the word pat. Or one could substitute ‘d’ for ‘t’ and get instead cad. In other words, ‘cat’ has three slots, c-a-t, and fillers for each slot come from the speech sounds of English.

The syllable is therefore itself an important part of the development of duality of patterning. It is a natural organising constraint set on the arrangement of phonemes that works to enable each phoneme to be better perceived. It has other functions, but the crucial point is that it is primarily an aid to perception, arising from the matching of ears to vocal apparatus over the course of human evolution, rather than a prespecified mental category.. A very simple characterisation of the syllable is that speech sounds are arranged in order. The order preferred most of the time is that, from left to right in the syllable, the sounds are arranged from least inherently loud to the loudest and then back to softest. This makes the sounds in each syllable easier to hear. It is another way of chunking that helps our brains to keep track of what is going on in language. This property is called sonority. In simple terms, a sound is more sonorous if it is louder. Consonants are less sonorous than vowels. And among consonants some (these need not worry us here) are less sonorous than others.‡ Thus syllables are units of speech in which the individual slots produce a crescendo-decrescendo effect, where the nucleus or central part is the most sonorous element – usually a vowel – while at the margins are the least sonorous elements. This is shown by the syllable bad. This is an acceptable syllable in English because b and d are less sonorous than a and are found in the margins of the syllable while a – the most sonorous element – is in the nuclear or central position. The syllable bda, on the other hand, would be ill-formed in English because a less sonorous sound, b, is followed by another less sonorous consonant sound, d, rather than immediately by an increase in sonority. This makes it hard to hear, or hard to distinguish b and d when they are placed together in the margin of the syllable.

Languages vary tremendously in syllabic organisation.§ Certain ones, like English, have very complicated syllable patterns. The word ‘strength’ has more than one consonant in each margin. And the consonant ‘s’ should follow the consonant ‘t’ at the beginning of ‘strength’ because it is more sonorant. So the word should actually be ‘tsrength’. It does not take this form because English has historically preferred the order ‘st’, based on sound patterns of earlier stages of English and the languages that influenced it, as well as cultural choice. History and culture are common factors that override and violate the otherwise purely phonetic organisation of syllables.

This perceptual and articulatory organisation of the syllable brings duality of patterning to language naturally. By organising sounds so that they can be more easily heard, languages in effect get this patterning for free. Each margin and nucleus of a syllable is part of the horizontal organisation of the syllable while the sounds that can go into the margin or nucleus are the fillers. And that means that the syllable in a sense could have been the key to grammar and more complex languages. Again, the syllable is based upon a simple idea: ‘chunk sounds so as to make them easier to hear and to remember’. Homo erectus would have probably have had syllables because they just follow from the shortness of our short-term memory in conjunction with the easiest arrangements to hear. If so, then this means that erectus would have had grammar practically given to them on a platter as soon as they used syllables. It is, of course, possible that syllables came later in language evolution than, say, words and sentences, but any type of sound organisation, whether in phonemes of Homo sapiens or other sounds by erectus or neanderthalensis, would entail a more powerful form for organising a language and moving it beyond mere symbols to some form of grammar. Thus early speech would have been a stimulus to syntagmatic and paradigmatic organisation in syntax, morphology and elsewhere in language. In fact, some other animals, such as cotton-top tamarins, are also claimed to have syllables. Whatever tamarins can do, the bet is that erectus could do better. If tamarins had better-equipped brains then they’d be on their way to human language.

If this is on the right track, duality of patterning, along with gestures and intonation, are the foundational organisational principles of language. However, once these elements are in place, it would be expected that languages would discover the utility of hierarchy, which computer scientists and psychologists have argued to be ever useful in the transmission or storage of complex information.

Phonology is, like all other forms of human behaviour, constrained by the memory–expression tension: the more units that a language has, the less ambiguously it can express messages, but the more there is to learn and memorise. So if a language had three hundred speech sounds, it could produce words that were less ambiguous than a language with only five speech sounds. But this has a cost – the language with more speech sounds is harder to learn. Phonology organises sounds to make them easier to perceive, adding a few local cultural modifications preferred by a particular community (as English ‘strength’ instead of ‘tsrength’). This gets to the co-evolution of the articulatory and auditory apparatuses. The relationship between humans’ ears and their mouths is what accounts for the sounds of all human languages. It is what makes human speech sounds different than, say, Martian speech sounds.

The articulatory apparatus of humans is, of course, also interesting because no single part of it – other than its shape – is specialised for speech. As we have seen, the human vocal apparatus has three basic components – moving parts (the articulators), stationary parts (the points of articulation), and airflow generators. It is worth underscoring again the fact that the evolution of the vocal apparatus for speech is likely to have followed the beginning of language. Though language can exist without well-developed speech abilities (many modern languages can be whistled, hummed, or signed), there can be no speech without language. Neanderthalensis did not have speech capabilities like those of sapiens. But they most certainly could have had a working language without a sapiens vocal apparatus. The inability of neanderthalensis to produce /i/, /a/ and /u/ (at least according to Philip Lieberman) would be a handicap for speech, but these ‘cardinal’ or ‘quantal’ vowels are neither necessary nor sufficient for language (not necessary because of signed languages, not sufficient because parrots can produce them).

Speech is enhanced as has been mentioned, when the auditory system co-evolves with the articulatory system. This just means that human ears and mouths evolve together. Humans therefore get better at hearing the sounds their mouths most easily make and making the sounds their ears most easily perceive.

Individual speech sounds, phones, are produced by the articulators – tongue and lips for the most part – meeting or approximating points of articulation – alveolar ridge, teeth, palate, lips and so on. Some of these sounds are louder because they offer minimal impedance to the flow of air out of the mouth (and for many out of the nose). These are vowels. No articulator makes direct contact with a point of articulation in the production of vowels. Other phones completely or partially impede the flow of air out of the mouth. These are consonants. With both consonants and vowels the stream of sounds produced by any speaker can be organised so as to maximise both information rate (consonants generally carry more information than vowels, since there are more of them) and perceptual clarity (consonants are easier to perceive in different positions of the speech stream, such as immediately preceding and following vowels and the beginnings and ends of words). Vowels and consonants, since speech is not digital in its production, but rather a continuous stream of articulatory movements, ‘assimilate’ to one another, that is they become more alike in some contexts, though not always the same contexts in every language. If a native speaker of English utters the word ‘clock’, the ‘k’ at the end is pronounced further back in the mouth than it is when they pronounce the word ‘click’. This is because the vowel ‘o’ is further back in the mouth and the vowel ‘i’ is further to the front of the mouth. In these cases, the vowel ‘pulls’ the consonant towards its place of articulation. Additional modifications to sounds enhance perception of speech sounds. Another example is known as aspiration – a puff of air made when producing a sound. Or voicing – what happens as the vocal cords vibrate while producing a sound. Syllable structure is another modification, when sounds are pronounced differently in different positions of a syllable. This is seen in the pronunciation of ‘l’ when it is at the end of a syllable, as in the word ‘bull’, vs ‘l’ when it is at the beginning of a syllable as in ‘leaf’. To literally see aspiration, hold a piece of paper about one inch in front of your mouth and pronounce the word ‘paper’. The paper will move. Now do the same while pronouncing the word ‘spa’. The paper will not move on the ‘p’ of ‘spa’ if one is a native speaker of English.

These enhancements are ignored often by native speakers when they produce speech because such enhancements are simply ‘add-ons’ and not part of the target sound. This is why native speakers of English do not normally hear a difference between the [p] of ‘spa’ and the [ph] of ‘paper’, where the raised ‘h’ following a consonant indicates aspiration. But to the linguist, these sounds are quite distinct. Speakers are unaware of such enhancements and usually can learn to hear them only with special effort. The study of the physical properties of sounds, regardless of the speakers’ perceptions and organisation of them, is phonetics. The study of the emic knowledge of speakers, what enhancements are ignored by native speakers and what sounds they target, is phonology.

Continuing on with our study of phonology, there is a long tradition that breaks basic sounds, vowels and consonants, down further into phonetic features, [+/− voiced] ‘voiced vs non-voiced’ or [+/− advanced tongue root], as in the contrast between the English vowels /i/ of beet and the vowel i of [bit] and so on. But no harm is done to the exposition of language evolution if such finer details are ignored.

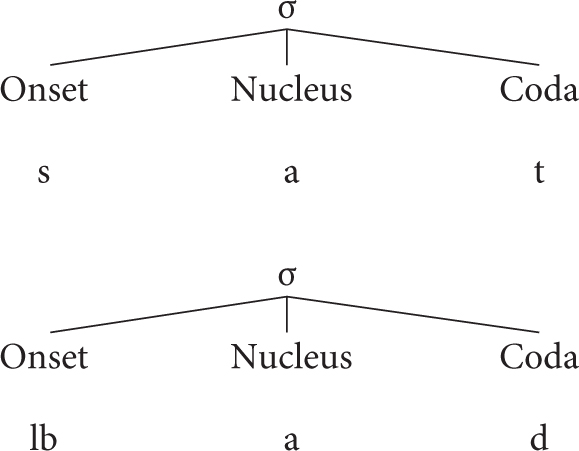

Moving up the phonological hierarchy we arrive once again at the syllable ‘the’, which introduces duality of patterning into speech sound organisation. To elaborate slightly further on what was said earlier about the syllable, consider the syllables in Figure 27.

As per the earlier discussion of sonority, it is expected that the syllable [sat] will be well formed, ceteris paribus, while the syllable [lbad] will not be because in the latter the sounds are harder to perceive.

The syllable is thus a hierarchical, non-recursive structuring of speech sounds. It functions to enhance the perceptibility of phones and often works in languages as the basic rhythmic unit. Once again, one can imagine that, given their extremely useful contributions to speech perception, syllables began to appear early on in the linking of sounds to meaning in language. They would have been a very useful and easy addition to speech, dramatically improving the perceptibility of speech sounds. The natural limitations of human auditory and articulatory systems would have exerted pressure for speakers to hear and produce syllabic organisation early on.

Figure 27: Syllables and sonority

However, once introduced, syllables, segments and other units of the phonological hierarchy would have undergone culture-based elaborations. Changes, in other words, are made to satisfy local preferences, without regard for ease of pronunciation or production. These elaborations are useful for group identification, as well as the perceptions of sounds in certain places in the words. So sometimes they are motivated by ease of hearing or pronunciation or by cultural reasons, in order to make sounds that identified one group as the source of those sounds, because speakers of one culture would have preferred some sounds to others, some enhancements to others and so on. A particular language’s inventory of sounds might also be culturally limited. This all means that in the history of languages, a set of cultural preferences emerges that selects among the sounds that humans can produce and perceive to choose the sounds that a particular culture at a particular time in the development of the language chooses to use. After this selection, the preferred sounds and patterns will change over time, subject to new articulatory, auditory, or cultural pressures, or via contact with other languages.

Other units of the phonological hierarchy include phonological phrases, groupings of syllables into phonological words or units larger than words. These phrases or words are also forms of chunking to aid working memory and to facilitate faster interpretation of information communicated. This segmentation is aided by gestures and intonation which offer backup help to speech for perception and working memory. In this way, the grouping of smaller linguistic units (such as sounds) into larger linguistic units (such as syllables and words and phrases) facilitates communication. Phrases and words are themselves grouped into larger groupings some linguists have referred to as ‘contours’ or ‘breath groups’ – groupings of sounds marked by breathing and intonation. We have mentioned that pitch, loudness and the lengthening or shortening of some words or phrases can be used to distinguish, say, new information from old information, such as the topic we are currently discussing (old information) and a comment about that topic (new information). These can also be used to signal emphasis and other nuances that the speaker would like the hearer to pick up on about what is being communicated. All of these uses of phonology emerge gradually as humans move from indexes to grammar. And every step of the way they would have in all likelihood been accompanied by gesture.

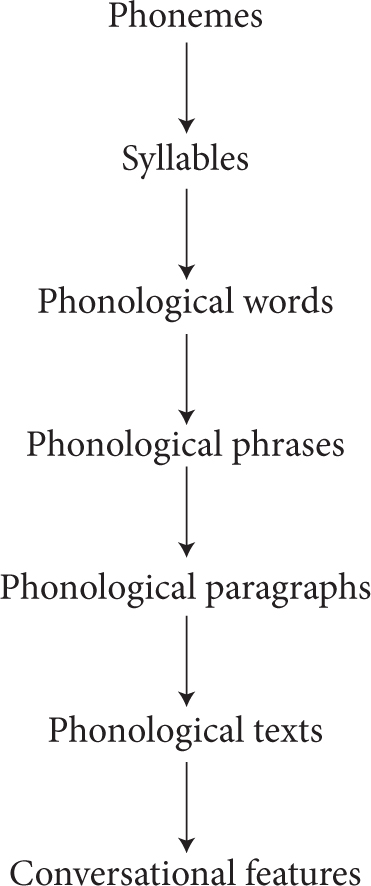

From these baby steps an entire ‘phonological hierarchy’ is constructed. This hierarchy entails that most elements of the sound structure of a given language are composed of smaller elements. In other words, each unit of sound is built up from smaller units via natural processes that make it easier to hear and produce the sounds of a given language. The standard linguistic view of the phonological hierarchy is given in Figure 28.

Our sound structures are also constrained by two other sets of factors. The first is the environment. Sound structures can be significantly constrained by the environmental conditions in which the language arose – average temperatures, humidity, atmospheric pressure and so on. Linguists missed these connections for most of the history of language, though more recent research has now established them clearly. Thus, to understand the evolution of a specific language, one must know something about both its original culture and its ecological circumstances. No language is an island.

Several researchers summarise these generalisations with the proposal that the first utterances of humans were ‘holophrastic’. That is, the first attempts at communication were unstructured utterances that were neither words nor sentences, simply interjections or exclamations. If an erectus used the same expression over and over to refer to a sabre-toothed cat, say, how might or would that symbol be decomposed into smaller pieces? Gestures, with functions that overlap intonation in some ways, contribute to decomposing a larger unit into smaller constituents, either reinforcing already highlighted portions or by indicating that other portions of the utterance are of secondary importance, but still more than portions of tertiary importance, and so on. To see how this might work, imagine that an erectus woman saw a large cat run by her and she exclaimed, ‘Shamalamadingdong!’ One of those syllables or portions of that utterance might be louder or higher pitched than the others. If she were emotional, that would necessarily come through in gestures and pitches that would intentionally or inadvertently highlight different portions of that utterance. Perhaps such as ‘SHAMAlamadingDONG!’ or ‘ShamaLAMAdingdong’ or ‘ShamalamaDINGdong’ or ‘SHAMAlamaDINGdong’, and so forth. If her gestures, loudness, pitch (high or low or medium) lined up with the same syllables, then those would perhaps begin to get recognition as parts of a word or sentence that began without any parts.

Figure 28: Phonological hierarchy

Prosody (pitch, loudness, length), gestures and other markers of salience (body positioning, eyebrow raising, etc.) have the joint effect of beginning to decompose the utterance, breaking it down into parts according to their pitch or gestures. Once utterances are decomposed, and only then, they can be (re)composed (synthesised), to build additional utterances. And this leads to another necessary property of human language: semantic compositionality. This is crucial for all languages. It is the ability to encode or decode a meaning of a whole utterance from the individual meanings of its parts.

Thus from natural processes linking sound and meaning in utterances, there is an easy path via gestures, intonation, duration and amplitude to decomposing an initially unstructured whole into parts and from there recomposing parts into wholes. And this is the birth of all grammars. No special genes required.

Kenneth Pike placed morphology and syntax together in another hierarchy, worth repeating here (though I use my own, slightly adapted version). This he called the ‘morphosyntactic hierarchy’ – the building up of conversations from smaller and smaller parts.

How innovations, linguistic or otherwise, spread and become part of a language is a puzzle known as the ‘actuation problem’. Just as with the spread of new words or expressions or jokes today, several possible enabling factors might be involved in the origin and spread of linguistic innovations. Speakers might like the sounds of certain components of novel erectus utterances more than others, or an accompanying pitch and/or gesture might have highlighted one portion of the utterance to the exclusion of other parts. As highlighting is also picked up by others and begins to circulate, for whatever reasons, the highlighted, more salient portion becomes more important in the transmission and perception of the utterance being ‘actuated’.

It is likely that the first utterance was made to communicate to someone else. Of course, there are no witnesses. Nevertheless the prior and subsequent history of the language progression strongly support this. Language is about communication. The possibly clearer thinking that comes when we can think in speech instead of merely, say, in pictures, is a by-product of language. It is not itself what language is about.

Figure 29: Morphosyntactic hierarchy

Just as there is no need to appeal to genes for syntax, the evidence suggests that neither are sound structures innate, aside from the innate vocal apparatus–auditory perception link between what sounds people can best produce and hear. The simplest hypothesis is that the co-evolution of the vocal apparatus, the hearing apparatus and linguistic organisational principles led to the existence of a well-organised sound-based system of forms for representing meanings as part of signs. There are external, functional and ecological constraints on the evolution of sound systems.¶

Syntax develops with duality of patterning and additions to it that are based on cultural communicational objectives and conventions, along with different grammatical strategies. This means that one can add recursion if it is a culturally beneficial strategy. One can have relative clauses or not. One can have conjoined noun phrases or not. Some examples of different grammar strategies in English include sentences like:

John and Mary went to town (a complex, conjoined noun phrase) vs John went to town. Mary went to town (two simple sentences).

The man is tall. The man is here (two simple sentences). vs The man who is tall is here (a complex sentence with a relative clause).

Morphology is the scientific term for how words are constructed. Different languages use different word-building strategies, though the set of workable strategies is small. Thus in English there are at most five different forms for any verb: sing, sang, sung, singing, sings. Some verbs have even fewer forms: hit, hitting, hits. There are really only a few choices for building morphological (word) structures. Words can be simple or composed of parts (called morphemes). If they are simple, without internal divisions, this is an ‘isolating’ language. Chinese is one illustration. In Chinese there is usually no past tense form for a verb. A separate word is necessary to indicate past tense (or just the context). So where we would say in English, ‘I ran’ (past tense) vs ‘I run’ (present tense), in Chinese you might say, ‘I now run’ (three words) vs ‘I yesterday run’ (three words).

In another language, such as Portuguese, the strategy for building words is different. Like many Romance languages (those descended from Latin), Portuguese words can combine several meanings. A simple example can be constructed from falo, which means ‘I speak’ in Portuguese.

The ‘o’ ending of the verb means several things at once. It indicates first person singular, ‘I’. But it also means ‘present tense’. And it also means ‘indicative mood’ (which in turn means, very roughly, ‘this really is happening’). The ‘o’ of falo also means that the verb is of the -ar set of verbs (falar ‘to speak’, quebrar ‘to break’, olhar ‘to look’, and many, many others). Portuguese and other languages descended from Latin, such as Spanish, Romanian, Italian, are known as Romance languages. They are referred to linguistically as ‘inflectional’ languages.

Other languages, such as Turkish and many Native American languages, are called ‘agglutinative’. This means that each part of each word often has a single meaning, unlike Romance languages, where each part of the word can have several meanings, as in the ‘o’ of falo. A single word in Turkish can be long and have many parts, but each part has but a single meaning:

Çekoslovakyalılaştıramadıklarımızdanmışsınızcasına ‘as if you were one of those whom we could not make resemble the Czechoslovakian people’.

Some inflectional languages even have special kinds of morphemes called circumfixes. In German the past tense of the verb spielen ‘to play’ is gespielt, where ge-and -t jointly express the past tense, circumscribing the verb they affect.

Other languages use pitch to add meaning to words. This produces what are called simulfixes. In Pirahã the nearly identical words ?áagá ‘permanent quality’ vs ?aagá ‘temporary quality’ are distinguished only by the high tone on the first vowel á. So I could say, Ti báaʔáí ?áagá ‘I am nice (always)’ or, Ti báaʔáí ?aagá ‘I am nice (at present)’.

Or one could express some meaning on the consonants and another part of the meaning of the word on the vowels, in which case we have a non-concatenative system. Arabic languages are of this type. But English also has examples. So foot is singular, but feet is plural, where we have kept the consonants f and t the same but changed the vowels.

It is unlikely that any language has a ‘pure’ system of word structure, using only one of these strategies just exemplified. Languages tend to mix different approaches to building words. The mixing is often caused by historical accidents, remnants of earlier stages of the language’s development or contact with other languages. But what this brief summary of word formation shows is that if we look at all the morphological systems of the world the basic principles are easy. This is summarised in Figure 30.#

Figure 30: Types of language by word type

These are the choices that every culture has to make. It could choose multiples of these, but simplicity (for memory’s sake) will favour less rather than more mixing of the systems. From the beginnings of the invention of symbols, at least 1.9 million years ago by Homo erectus, there has been sufficient time to discover this small range of possibilities and, via the grammar, meaning, pitches and gestures of language, to build morphological systems from them.**

Arguably the greatest contribution Noam Chomsky has made to the understanding of human languages is his classification of different kinds of grammars, based on their computational and mathematical properties.2 This classification has become known as the ‘Chomsky hierarchy of grammars’, though it was heavily influenced by the work of Emile Post and Marcel Schützenberger.

Yet while Chomsky’s work is insightful and has been used for decades by computer scientists, psychologists and linguists, it denies that language is a system for communication. Therefore, in spite of its influence, it is ignored here in order to discuss a less complicated but arguably more effective way of looking at grammar’s place in the evolution of language as a communicative tool. The claim is that, contrary to some theories, there are various kinds of grammars available to the world’s languages and cultures (linear grammars, hierarchical grammars and recursive hierarchical grammars). These systems are available to all languages and they are the only systems for organising grammar. There are only three organisational templates for human syntax. In principle, this is not excessively difficult.

A linear grammar would be an arrangement of words left to right in a culturally specified order. In other words, linear grammars are not merely the stringing of words without thought. A language might stipulate that the basic order of its words is subject noun + predicate verb + direct object noun, producing sentences like ‘Johnsubject noun hitpredicate verb Billdirect object noun.’ Or, if we look at the Amazonian language Hixkaryana, the order would be object noun + predicate verb + subject noun. This would produce ‘Billobject noun hitpredicate verb Johnsubject noun,’ and this sentence would be translated into English from Hixkaryana, in spite of its order of words, as ‘John hit Bill.’ These word orders, like all constituents in human languages, are not mysterious grammatical processes dissociated from communication. On the contrary, the data suggest that every bit of grammar evolves to aid short-term memory and the understanding of utterances. Throughout all languages heretofore studied, grammatical strategies are used to keep track of which words are more closely related.

One common strategy of linking related words is to place words closer to words whose meaning they most affect. Another (usually in conjunction with the first) is to place words in phrases hierarchically, as in one possible grammatical structure for the phrase John’s very big book shown in Figure 31.

In this phrase there are chunks or constituents within chunks. The constituent ‘very big’ is a chunk of the larger phrase ‘very big book’.

One way to keep track of which words are most closely related is to mark them with case or agreement. Greek and Latin allow words that are related to be separated by other words in a sentence, so long as they are all marked with the same case (genitive, ablative, accusative, nominative and so on).

Consider the Greek sentences below, transcribed in English orthography, all of which mean ‘Antigone adores Surrealism’:

|

(a) |

latrevi |

ton iperealismo |

i Antigoni |

Verb |

Object |

Subject | |

adoreverb |

the surrealismaccusative |

the Antigoninominative | |

|

(b) |

latrevi i Antigoninominative |

ton iperealismoaccusative | |

Verb |

Subject |

Object | |

adoreverb |

the Antigoninominative |

the surrealismaccusative | |

|

(c) |

i Antigoni |

latrevi |

ton iperealismo |

Subject |

Verb |

Object | |

the Antigoninominative |

adoreverb |

the surrealismaccusative | |

|

(d) |

ton iperrealismo |

latrevi |

i Antigoni |

Object |

Verb |

Subject | |

the surrealismaccusative |

adoreverb |

the Antigoninominative | |

|

(e) |

i Antigoni |

ton iperealismo |

latrevi |

Subject |

Object |

Verb | |

the Antigoninominative |

the surrealismaccusative |

adoreverb | |

|

(f) |

ton iperealismo |

i Antigoni |

latrevi |

Object |

Subject |

Verb | |

the surrealismaccusative |

the Antigoninominative |

adoreverb |

All of these sentences are grammatical in Greek. All are regularly found. The Greek language, like Latin and many other languages, allows freer word order than, say, English, because the cases, such as ‘nominative’ and ‘accusative’ distinguish the object from the subject. In English, since we rarely use case, word order, not case, has been adopted by our culture as the way to keep straight who did what to whom.

But even English has case to a small degree: Inominative saw himobjective, Henominative saw meobjective, but not *Me saw he or *Him saw I. English pronouns are marked for case (‘I’ and ‘he’ are nominative; ‘me’ and ‘him’ are objective).

We see agreement in all English sentences, as in ‘He likes John.’ Here, ‘he’ is third person singular and so the verb carries the third person singular ‘s’ ending on ‘likes’ to agree with the subject, he. But if we say instead, ‘I like John,’ the verb is not ‘likes’ but ‘like’ because the pronoun ‘I’ is not third person. Agreement is simply another way to keep track of word relationships in a sentence.

Placing words together in linear order without additional structure is an option used by some languages to organise their grammars, avoiding tree structures and recursion. Even primates such as Koko the gorilla have been able to master such word order-based structures. It certainly would have been within the capabilities of Homo erectus to master such a language and would have been the first strategy to be used (and is still used in a few modern languages, such as perhaps Pirahã and the Indonesian language Riau).

One thing that all grammars must have is a way to assemble the meanings of the parts of an utterance to form the meaning of the whole utterance. How do the three words, ‘he’, ‘John’ and ‘see’, come to mean ‘He sees John’ as a sentence? The meaning of each of the words is put together in phrases and sentences. This is called compositionality, without which there can be no language. This property can simply be built off the phrases in a tree structure directly, which is the case for most languages, such as English, Spanish, Turkish and thousands of others. But it can also be built in a linear grammar. In fact, even English shows that compositionality doesn’t need complex grammar. The utterance ‘Eat. Drink. Man. Woman.’ is perfectly intelligible. But as the meaning is put together, it relies heavily on our cultural knowledge. The absence of complex (or any) syntax doesn’t scuttle the meaning.

Many languages, if not all, have examples of meaningful sentences with little or no syntax. (Another example from English would be ‘You drink. You drive. You go to jail.’ These three sentences have the same interpretation as the grammatically distinct and more complex construction, ‘If you drink and drive, then you will go to jail.’) Note that the interpretation of separate sentences as a single sentence does not require prior knowledge of other syntactic possibilities, since we are able to use this kind of cultural understanding to interpret entire stories in multiple ways. One might object that sentences without sufficient syntax are ambiguous – they have multiple meanings and confuse the hearer. But, as noted in chapter 4, even structured sentences like ‘Flying planes can be dangerous’ are ambiguous, in spite of English’s elaborate syntax. One could eliminate or at least reduce ambiguity in a given language, but the means for doing so always include making the grammar more difficult or the list of words longer. And these strategies only make the language more complicated than it needs to be, by and large. So this is why, in all languages, ambiguous sentences are interpreted through native speaker knowledge of the context, the speaker and their culture.

The more closely the syntax matches the meaning, usually the easier the interpretation is. But much of grammar is a cultural choice. The form of a grammar is not genetically predestined. Linear grammars are not only the probable initial stage of syntax, but also still viable grammars for several modern languages, as we have seen. A linear grammar with symbols, intonation and gestures is all a G1 language – the simplest full human language – requires.

The next type of languages are G2 languages. These are languages that have hierarchical structures (like the ‘tree diagrams’ of sentences and phrases), but lack recursion. Some have claimed that Pirahã and Riau are examples. Yet we need not focus exclusively on isolated or rarely spoken languages such as these. One researcher, Fred Karlsson, claims that most European languages have hierarchy but not recursion.

Karlsson bases his claim on the observation: ‘No genuine triple initial embeddings nor any quadruple centre-embeddings are on record (“genuine” here means sentences produced in natural non-linguistic contexts, not sentences produced by professional linguists in the course of their theoretical argumentation).’3 ‘Embedding’ refers to placing one element inside another. Thus one can take the phrase ‘John’s father’ and place this inside the larger phrase ‘John’s father’s uncle’. Both of these are embedding. The difference between embedding (which is common in languages that, according to researchers like Karlsson, have hierarchical structures without recursion) and recursion is simply that there is no bound on recursion, it can keep on going. So what Karlsson is saying is that in Standard Average European (SAE) languages he only found sentences like:

John said that Bill said that Bob is nice, or even

John said that Bill said that Mary said that Bob is nice, but never sentences like

John said that Bill said that Mary said that Irving said that Bob is nice.

The first sentence of this triplet has one level of embedding, the second has two and the third has three. But the claim is that standard European languages never allow more than two levels of embedding. Therefore, they have hierarchy (one element inside another), but they do not have recursion (one element inside another inside another … ad infinitum).

According to Karlsson’s research it does not appear that any SAE language is recursive. He acknowledges that one could argue that they are recursive in an abstract sense, or that they are generated by a recursive process. But such an approach doesn’t seem to match the facts in his analysis. In other words, Karlsson claims, to use my terms, that all of these languages are G2 languages. Karlsson’s work is therefore interesting support from modern European languages that G2 languages exist, as per the semiotic progression. Again, these are languages that are hierarchical but not recursive. To show beyond doubt that a language is recursive we need to show ‘centre-embedding’. Other forms are subject to alternative analyses:

(a) Centre-embedding: ‘A man that a woman that a child that a bird that I heard saw knows loves sugar.’

(b) Non-centre-embedding: ‘John said that the woman loves sugar.’

What distinguishes (a) is that the subordinate clauses, ‘that a woman that a child that a bird I heard saw knows’ are surrounded by constituents of the main clause, ‘A man loves sugar’. And ‘that a child’ is surrounded by bits of the clause it is embedded within ‘a woman knows’, and ‘that a bird’ is surrounded by parts of its ‘matrix’ clause ‘a child saw’ and so on. These kinds of clauses are rare, though, because they are so hard to understand. In fact, some claim that they exist only in the mind of the linguist, though I think that is too strong.

In (b), however, we have one sentence following another. ‘John said’ is followed by ‘that the woman loves sugar’. Another possible analysis is that ‘John said that. The woman loves sugar.’ This analysis (proposed by philosopher Donald Davidson) makes English look more like Pirahã.4

The final type of language I am proposing in line with Peirce’s ideas, G3, must have both hierarchy and recursion. English is often claimed to be exactly this type of language, as previous examples show. As we saw earlier some linguists, such as Noam Chomsky, claim that all human languages are G3 languages, in other words, that all languages have both hierarchy and recursion. He even claims that there could not be a human language without recursion. The idea is that recursion is what separates in his mind the communication systems of early humans and other animals from the language of Homo sapiens. An earlier human language without recursion would be a subhuman ‘protolanguage’ according to Chomsky.††

However, the fact remains that no language has been documented in which any sentence is endless. There may be theoretical reasons for claiming that recursion underwrites all modern human languages, but it simply does not match the facts of either modern or prehistoric languages or our understanding of the evolution of languages.

There are many examples in all languages that show non-direct connection between syntax and semantics. In discourses and conversations, moreover, the meanings are composed by speakers from disconnected sentences, partial sentences and so on. This supports the idea that the ability to compose the larger meanings of conversations from their parts (or ‘constituents’) is mediated by culture. As with G1 languages and people suffering from aphasia, among many other cases, meaning is imputed to different utterances by loosely applying cultural and individual knowledge. Culture is always present in interpreting sentences, though, regardless of the type of grammar, G1, G2, or G3. We know not exactly which of these three grammars, or all three, were spoken by Homo erectus communities, only that the simplest one, G1, would have been and still is adequate as a language, without qualification.

It should ultimately be no surprise that Homo erectus was capable of language, nor that a G1 language would have been capable of taking them across the open sea or leading them around the world. We are not the only animals that think, after all. And the more we can understand and appreciate what non-human animals are mentally capable of, the more we can respect our own Homo erectus ancestors. One example of how animals think is Carl Safina’s book Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel. Safina makes a convincing case that animal communication far exceeds what researchers have commonly noticed in the past. And other researchers have shown that animals have emotions very similar to human emotions. And emotions are crucial in interpreting others and wanting to communicate with them, wanting to form a community. Still, although animals make use of indexes regularly and perhaps some make sense of icons (such as a dog barking at a television screen when other dogs are ‘on’ the screen), there is no evidence of animals using symbols in the wild.‡‡

Among humans, however, as we have seen, there is evidence that both Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis used symbols. And with symbols plus linear order we have language. Adding duality of patterning to this mix, an easy couple of baby steps get us to ever more efficient languages. Thus possession of symbols, especially in the presence of evidence that culture existed, evidence strong for both erectus and neanderthalensis, indicates that it is highly likely that language was in use in their communities.

It is worth repeating that there is no need for a special concept of ‘protolanguage’. All human languages are full-blown languages. None is inferior in any sense to any other. They each simply use one of three strategies for their grammars, G1, G2, or G3. Thus I find little use for this notion, given the theory of language evolution here.

The question of ‘what evolved’, therefore, eventually gets us back to two opposing views of the nature of language. One is Chomsky’s, which Berkeley philosopher John Searle describes as follows:

The syntactical structures of human languages are the products of innate features of the human mind, and they have no significant connection with communication, though, of course, people do use them for, among other purposes, communication. The essential thing about languages, their defining trait, is their structure. The so-called ‘bee language’, for example, is not a language at all because it doesn’t have the right structure and the fact that bees apparently use it to communicate is irrelevant. If human beings evolved to the point where they used syntactical forms to communicate that are quite unlike the forms we have now and would be beyond our present comprehension, then human beings would no longer have language, but something else.5

Searle concludes, ‘It is important to emphasize how peculiar and eccentric Chomsky’s overall approach to language is.’

A natural reply to this would be that what is one person’s ‘peculiar and eccentric’ is another person’s ‘brilliantly original’. There is nothing wrong per se with swimming against the current. The best work often is eccentric and peculiar. But I want to argue that Chomsky’s view of language evolution is to be questioned not simply because it is original, but because it is wrong. He has continued to double-down on this view for decades. In his recent book on language evolution with MIT professor of Computer Science Robert Berwick, Chomsky presents a theory of language evolution which furthers his sixty-year-old programme of linguistic theorising, the programme that Searle questions above. Chomsky’s view was so novel and shocking in the 1950s that it was initially thought by many to have revolutionised linguistic theory and been the first shot fired in the ‘cognitive revolution’ that some date to a conference at MIT on 11 September 1956.

But Chomsky’s linguistic theory was neither a linguistic revolution nor a cognitive one. In the 1930s Chomsky’s predecessor, and I would say his inspiration, Leonard Bloomfield, along with Chomsky’s PhD thesis supervisor Zellig Harris, developed a theory of language remarkably like Chomsky’s, in the sense that structure rather than meaning was central and communication was considered secondary. And another predecessor of Chomsky’s, Edward Sapir, had since the 1920s argued that psychology (what some today would call cognition) interacted with language structures and meanings in profound ways. In spite of these influences, Chomsky has staked out his claims to originality clearly over the years, reiterating them in his new work on evolution, namely that ‘language’ is a computational system, not a communication system.§§

So for Chomsky there is no language without recursion. But the evidence from evolution and modern languages paints a different picture. According to the evidence, recursion would have begun to appear in language, as we saw earlier, via gestures, prosodies and their contributions to the decomposition of holophrastic utterances.

As speech sounds produced auditory symbols (words and phrases) these symbols would have been used in larger strings of symbols. Gestures and intonation, whether precisely aligned or only perceived to be aligned with specific parts of utterances, would have led to a decomposition of symbols. Other symbols could have been derived from utterances that had little internal structure initially, but were then likewise broken down via gestures, intonation and so on.

The bottom line is that recursion is secondary to communication and that the fundamental human grammar that made possible the first human languages was a G1 grammar.¶¶

Chomsky’s grammar-first theory is disconnected from the data of human evolution and the cultural evidence for the appearance of advanced communication. It ignores Darwinian gradual evolution, having nothing to say about the evolution of icons, symbols, gestures, languages with linear grammars and so on, in favour of a genetic saltation endowing humans with a sudden ability to do recursion. Again, according to this theory, communication is not the principal function of language. While all creatures communicate in one way or another, only humans have anything remotely like language because only humans have structure-dependent rules.##

* This diagram comes from the linguistic theory known as Role and Reference Grammar, one of the only theories of language in existence that concerns itself with the whole utterance, not just its syntax.

† Gestures are also crucial to understanding how duality and compositionality happen.

‡ In Dark Matter of the Mind I offer a sustained discussion of phonology related to Universal Grammar, and I severely criticise the notion that either sonority or phonology is an innate property of human minds.

A commonly used representation of the ‘sonority hierarchy’ is: [a] > [e o] > [i u] > [r] > [l] > [m n ŋ] > [z v ð] > [s f θ] > [b d g] > [p t k].

§ I have written extensively on syllables in Amazonian languages, which are particularly interesting theoretically.

¶ Sign languages do not have phonologies, except in a metaphorical sense, though they do organise gestures in ways reminiscent of sound structures. Fully developed sign languages usually arise when phonologies are unavailable (through deafness or lack of articulatory ability) or when other cultural values render gestures preferable. Since gestures are related to the eyes rather than the ears, their organising principles are different in some ways. Of course, because both phonological and gestural languages are designed by cultures and the minds, subject to similar constraints of computational utility, they will also have features in common, as is often observed in the literature.

# One example of a a nonconcatenative process comes from English, where ‘foot’ is singular and ‘feet’ is plural, with one vowel substituting for another. Another famous set of cases comes from Semitic languages, such as Hebrew, as seen in the example below:

‘he dictated’ (causative active v.) is TB?n ‘hih’tiv’, while ‘it was dictated’ (causative passive v.) is nrqri ‘huh’tav’

** There is some overlap between the account presented here and an independently developed set of proposals by Erkki and Hendrik Luuk: ‘The Evolution of Syntax: Signs, Concatenation and Embedding’ (Cognitive Systems Research 27, 2014: 1–10), a very important article in the literature on the evolution of syntax. Like the account below, Luuk and Luuk argue that syntax develops initially from the concatenation of signs, moving then from mere concatenation to embedding grammars. My differences with their proposals, however, are many. For one thing, they seem to believe, which is common enough, that compositionality depends on syntactic structure, failing to recognise that semantic compositionality is facilitated by syntactic structure, but not dependent on it in all languages. Further, they fail to recognise the cultural context and why therefore modern languages do not need embedding. They do seem to embrace my view that language is a cultural tool.

†† See Marc Hauser, Noam Chomsky and Tecumseh Fitch, ‘The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, How Did It Evolve?’ Science 298, 2002: 1569–1579. Though the authors use the term ‘recursion’, they now claim that they do not mean recursion as understood by people doing research outside of Chomsky’s Minimalism, but they actually intend Merge, a special kind of grammatic operation. This has caused tremendous confusion, though, ultimately, the issues do not change and Merge has been falsified in several modern grammars (see my Language: The Cultural Tool, among many others).

‡‡ This is not to say that animals could not use symbols. I just am not aware of any well-supported or widely accepted claims that they can, in the wild. I certainly accept the idea that gorillas and other creatures have been taught to use symbols in the lab, and there are cases of animals, such as Koko the gorilla, using symbols after instruction.

§§ More technically, language is nothing more nor less than a set of endocentric, binary structures created by a single operation, Merge, and only secondarily used for storytelling, conversation, sociolinguistic interactions and so forth.

¶¶ Recursion simply allows speakers to pack more information into single utterances. So while ‘You commit the crime. You do the time. You should not whine.’ are three separate utterances we can say the same thing in one utterance using recursion: ‘If you commit a crime and do the time, you should not whine.’

## This is circular in the sense that Chomsky takes a feature that only humans are known to have, structure-dependency, and claims that, because this defines language, only humans have language.