The Science of the Gods

THE UNIVERSAL GODS

The ancients commonly held that God administers the universe by means of the gods—universal gods and celestial gods—who carry out divine will on different scales of time and space.

In the Vedic tradition, the universal gods (vishva-devas) correspond directly to the universal layers of consciousness that lie above the half measure. These are also known as immortal gods because they possess imperishable bodies of Logos (instead of perishable bodies of Cosmos).

Each universal god above (endowed with synthetic power) was viewed as “married” to its own creative power (shakti) below (endowed with analytic power); the gods and their powers are compared to husbands and wives or divine couples engaged in creative union. Therefore, the gods and their shaktis correspond to the sets of matched pairs outlined in chapter 3. The two sets of layers are compared literally to the fathers and mothers of creation. By means of their creative unions the divine couples conceive the universe, the perishable from the imperishable, as the divine embryo (hiranyagarbha) or cosmic egg (brahmanda) within the unbounded cosmic womb.

Although tradition held that both the gods and their shaktis are required to conceive the universe, the act of creation is initiated not by the shaktis, but by the gods above. Just as an egg in the female womb is incapable of developing into an embryo unless it is first inseminated by male seed, so the layers above were viewed as inseminating the layers below with the synthetic power of consciousness, so that the otherwise incoherent and local parts of creation might become nonlocally organized into coherent wholes—or conscious created beings.

In this sense, the gods above were viewed as stronger than their powers below, because they have the potential to infuse the analytic fields of force and matter with the self-organizing power of consciousness. The Hermetic sages taught a similar principle: “All the world which lies below has been set in order and filled with contents by the things which are placed above; for the things below have not the power to set in order the world above. The weaker mysteries, then, must yield to the stronger; and the system of things on high is stronger than the things below in as much as it is secure from disturbance and not subject to death.”1

Even though the strength of the synthetic powers above may be equal mathematically to the strength of the analytic powers below, they were still viewed as stronger, because they have the potential to infuse with consciousness otherwise incoherent matter-energy. The universal gods and their shaktis represent all-pervading fields of consciousness that span a particular range of space-time scales. God, the Supreme Being, on the other hand, was viewed as the one eternal self of them all. Unlike the gods and their shaktis, who embrace a particular range of scales, the awareness of God spans the entire spectrum of scales, ranging from the infinitesimal to the infinite.

Unlike God, the Supreme Being, the gods were viewed not as fully omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent, but as limited aspects of the Supreme Being who possessed limited values of knowledge, power, and presence.

THE CELESTIAL GODS

The created offspring of the universal gods were known as the celestial gods. These represent the conscious forms of material existence that appear as the stars, solar systems, galaxies, and so forth—as those bodies that shine in the night sky. Unlike the universal gods, which are immortal, the celestial gods are mortal; they possess mortal bodies composed of ordinary matter-energy.

Unlike the mortal human body, the body of a celestial god may persist for millions or billions of years. As compared to human beings on earth, then, the celestial gods were viewed as relatively immortal—though, in the final analysis, their bodies are mortal; they were created at some point in time, and they will dissolve at some point.

Although a given celestial god may have a body that displays the form of a luminous sphere composed of matter-energy, that sphere is not insentient; it represents a celestial “godhead” that is filled with pure knowledge and self-organizing power. Each such celestial godhead provides an operative basis, or a point of view, for the universal gods and their shaktis within the physical Cosmos. Ultimately, however, all the gods represent different aspects of God, the Supreme Being, who is the very self of them all, whether universal or celestial.

THE LIVING UNIVERSE

According to the seers, the highest of the celestial gods has a cosmic body that corresponds to the body of the Cosmos as a whole. In the Hermetic texts, this great god was simply called Cosmos, the embodiment of the living universe: “Now this whole Cosmos—which is a great god, and an image of Him who is greater . . . is one mass of life; and there is not anything in the Cosmos, nor has been through all of time from the foundation of the universe, neither in the whole nor among the various things contained in it, that is not alive.”2

The idea that the universe and everything in it is alive and endowed with consciousness is consistent with the ancient subjective paradigm, which suggests that everything in the universe has its ultimate origin in the field of pure consciousness. This includes not only the celestial bodies that appear as the cosmological wholes above, but also the elementary particles that appear as the microscopic parts below. In this regard, we must draw a distinction between the universal gods, which correspond to all-pervading fields of consciousness (or universal vacuum states), and the elementary constituents of those fields, which correspond to disembodied souls.

As we have seen, in the Vedic tradition, the soul was called variously the jiva or purusha, which in a disembodied state has the form of a point value of consciousness. These point values represent the elementary constituents of the universal fields of consciousness. Yet not all point values are the same. The Vedic texts tell us that there are two types of souls in the world, the perishable (kshara) and imperishable (akshara): “There are these two [types of] souls in the world—perishable and imperishable. The perishable consists of all the elements. The immovable multitude is called imperishable. But the highest soul is another, called the supreme Self. . . .” 3

This very revealing passage suggests that the perishable souls—the perishable point values of consciousness—correspond to “all the elements” (sarva bhutani) of creation. In other words, they correspond to the elementary particles. In both classical and quantum mechanics, the elementary particles are treated as infinitesimal point particles, which are nevertheless endowed with certain properties, such as mass, charge, momentum, and energy. There is no notion that one of these properties is consciousness, so that an elementary particle can be conceived as an elementary soul—but that was precisely the position of the ancients: Each elementary particle was viewed as a perishable point value of consciousness.

The idea that these point values are perishable is consistent with quantum theory, in which the elementary particles are viewed as being created constantly and annihilated constantly at a frequency that transcends all means of empirical observation. In the Vedic texts, this constant process of creation and annihilation was called nitya pralaya and was attributed to the force of time:

Some men, knowing the subtle state of things . . . declare the creation and dissolution of all beings, from Brahma [the Cosmos] downward, as taking place all the time. The successive stages undergone by all changing things serve as an index of the constant creation and dissolution of those things, as carried out by the force of time. These [high frequency] stages [of creation and annihilation], brought about by the force of time . . . are not perceived [by ordinary men]. 4

The point values of consciousness caught up in this constant process of creation and annihilation were viewed as perishable souls, which constitute “all the elements” of creation. These correspond to the movable point values of consciousness from which is fashioned the perishable form of the Cosmos. The imperishable souls, on the other hand, correspond to the immovable point values from which is fashioned the imperishable form of the metaphysical Logos. This is none other than the crystalline structure of the transcendental superlattice, wherein each lattice point serves as the seat of an imperishable soul.

Unlike the perishable soul, which is movable, the imperishable soul is immovable; it does not have the freedom to move through space, and therefore has no interpretation as a particle or element of creation. Rather, the imperishable souls collectively form an “immovable multitude” (kutastha), which defines the quantum geometry of transcendental space itself. That crystalline geometry is none other than the transcendental superlattice, which represents the ideal form of the metaphysical Logos.

Although the imperishable souls are immovable, this does not mean that they lack freedom. They may be eternally frozen in place, but they are free to expand and contract their scales of subjective comprehension over the entire spectrum of consciousness. This amounts to a completely different type of freedom from that enjoyed by the perishable soul.

The field of pure consciousness includes both types of point values. In the passage quoted above, it is referred to as the highest soul, which serves as the one supreme self of all the point values—whether perishable or imperishable. By means of the perishable soul, the self obtains various points of view regarding the movable reality of the physical Cosmos, and by means of the imperishable soul, it obtains viewpoints regarding the immovable reality of the metaphysical Logos. In the final analysis, the same eternal self possesses both points of view.

That self, in turn, has various manifestations of space and time on different scales as all-pervading fields of consciousness, which can be viewed variously as universal layers, universal gods, or universal vacuum states. Each of these fields acts as the presiding deity, or self, of all the pointlike souls—both perishable and imperishable—that operate under its jurisdiction.

For this reason, the Hermetic texts tell us that the layers serve as the haunts of disembodied souls, the point values of consciousness, which provide the field with various points of view on its own reality. These souls constitute the conscious and living parts from which are composed both the physical Cosmos and metaphysical Logos. Their behavior is directed by the universal gods, and ultimately by God, the Supreme Being, who is the very self of them all.

THE CREATOR

The Vedic texts make a distinction between God, the Supreme Being, and God, the Creator. The Supreme Being was called Brahman (neutral gender), while the Creator was called Brahma (masculine gender). In effect, Brahma represents the living embodiment of Brahman.

The great god called Brahma in the Vedic texts is identical to the great god called Cosmos in the Hermetic texts. He represents the celestial embodiment of the entire living universe as a whole. Brahma was also called the adi-purusha (the first soul), because he was viewed as the first enlightened soul to be born at the beginning of creation—before anything whatsoever was actually created. Yet rather than being born from any mortal womb, he was born from the cosmic womb as a disembodied soul, a point value of consciousness, which nevertheless has the potential for infinity.

According to the Vedic creation myths, when Brahma was first born from the cosmic womb, or field of pure ignorance, he appeared as a thumb-size soul. Having come from the field of pure ignorance, the Creator was initially ignorant of who he was and why he had been born. Therefore, Brahma’s first utterance was “Ka?”—Sanskrit meaning “Who am I?” For this reason, he was initially known as the divine Ka, and an entire hymn is dedicated to him in the Rig Veda.

The myth goes on to tell us that God, the Supreme Being, informed his firstborn son that he was destined to become the Creator of the universe. Having received this instruction, Brahma then tried to create the universe, but could not succeed—he did not have the necessary knowledge, presence, or power. Feeling that he had failed in his mission, he turned to his Father for advice, and received the instruction to perform tapas.

The Sanskrit word tapas means “heating,” but it refers to the process of spiritual introspection whereby the senses are turned away from their objects toward the self. The instruction Brahma received therefore had to do with the process of transcendence whereby the space-time ideas associated with one layer are dissolved into the self so that a new, expanded set of space-time ideas can be conceived. The process of dissolving one set of ideas into the self to make way for a new set may be compared to a process of self-sacrifice: our preconceived ideas are offered to the fire of pure knowledge so that they are consumed and reduced to ashes. It is by means of tapas that the soul ascends from one layer to another.

In the beginning, the creative power of the Creator was weak because his awareness spanned only the first two layers of the cosmic spectrum, which lie immediately above and below the half measure. To realize his full creative power, he had to ascend and descend the divine ladder until his awareness reached the microscopic and macroscopic limits of creation. These limits mark the divine station of the Creator above and his shakti below. The Creator ascended the divine ladder by performing tapas. In the process, the universal gods—the dormant layers of consciousness—became warmed; the universal vacuum states became filled with the virtual excitations of light and sound, which were previously unseen and unheard.

The Vedic texts tell us that at this stage the universe existed as a “pure creation” (shuddha srishti), a virtual creation; no real forms of matter and energy were yet created. For empirical purposes, the universe at this stage would have resembled the vacuum of empty space—but the vacuum was not really empty. It was filled with virtual excitations of transcendental light and sound, which had been warmed or enlivened by the ascending and descending awareness of the Creator, the first enlightened soul in creation. We may compare the virtual creation to the warmed state of a seed prior to its actual sprouting. At that stage, all things existed only in a virtual or spiritual form, and the layers assumed the form of virtual vacuum states.

Upon arriving at his own divine station, the Creator became the embodiment of all the universal gods directly responsible for upholding the created appearance of the universe and of all the virtual vacuum states that exist on different scales of space and time. Having awakened or warmed the universal gods, the Creator then directed them to create the universe by transforming the virtual universe into the real universe. This was called the “impure creation” (ashuddha srishti).

Through his own divine will (which is nonlocal), by means of pure intention, he directed the gods to create the universe. In this way, the gods created all the material worlds and all the beings that inhabit them—the manifest from the unmanifest, or the real from the virtual. The Creator obtained the power to create when he ascended to his own divine station, because his awareness then embraced a vast spectrum of space-time scales. As a result, the analytic and synthetic powers of his awareness were enormous in strength—strong enough to conceive and create the entire universe. At that point, his awareness grasped simultaneously the whole blueprint of creation spanning billions of light-years, as well as all the microscopic parts of creation, by means of which that blueprint was to be executed over the course of billions of years.

This ancient Vedic myth has direct relevance to the enlightened human soul. Like the Creator, the enlightened soul is first born thumb-size from the cosmic womb. In order to grow to become like its Father, it must follow in the footsteps of the Creator. After being born, it must perform tapas and ascend the divine ladder, step by step, until it arrives at the station of the Creator. In the process, the enlightened soul experiences again the mechanics by which the universe was first created. By balanced ascending and descending of the divine ladder, it experiences the progressive enlivenment of the universal vacuum states, which correspond to the metaphysical layers above and below. Upon arriving at the station of the Creator, the enlightened soul becomes identified with the Creator, and conceives the entire universe as its own cosmic body.

This marks a major milestone on the path of immortality, which was emphasized by the ancient seers. At that point, the soul grasps the limits of creation as well as the largest and smallest space-time scales that have direct relevance to the creation of the universe.

THE CANONICAL SET OF THIRTY-THREE GODS

The station of the Creator marks the shore of this world. Beyond that lies the great mystery, which leads ultimately to full immortality in the bosom of the infinite. Upon reaching the station of the Creator, the enlightened soul becomes identified with both the full set of universal gods directly responsible for upholding the created appearance of the universe and the full set of celestial gods, who administer the universe as so many godheads.

According to the Vedic seers, the created appearance of the universe is upheld by a set of thirty-three universal gods and their thirty-three universal shaktis. These gods constitute the religious canon of the Vedic tradition and directly correspond to the first thirty-three layers above the half measure, while their shaktis correspond to the first thirty-three layers below.

If we accept this picture as authoritative, then for all empirical purposes we can restrict our analysis to the first thirty-three layers above and below the half measure. The universal rule of thumb can then be used to predict that the limits of creation are characterized by two matched scales on the order of 2 × 1032 centimeters and 2 × 10-33 centimeters.

THE WHOLE TREE OF LIFE

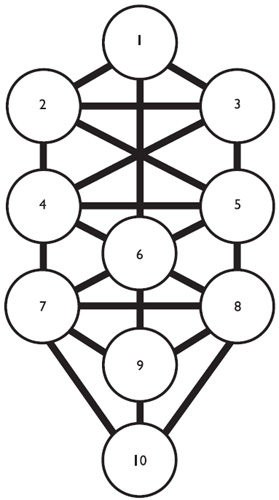

The Vedic notion of thirty-three universal gods is supported in the Hebrew tradition of kabbalah in which the cosmic body of Adam Ouila, who represents the first archetypal soul, is symbolized by the Etz Chaim, the diagrammatic Tree of Life.

This diagram, which lies at the very heart of the tradition, provides a geometric representation of the fundamental categories on the basis of which the universe is fashioned. The Tree of Life symbolizes the metaphysical Logos, the mere taste of which has the potential to render the soul immortal. In this regard, Adam Ouila, the first archetypal soul, provides a Hebrew conception of the universal being known in the Vedic tradition as Brahma, the first soul, and in the Hermetic tradition as Cosmos, the great god.

The wisdom associated with the Tree of Life suggests that the geometric elements of the diagram correspond to the “bones” of Adam Ouila. This has deep meaning. When the perishable body dies, the soft tissues of the body decay, but the bones remain. The bones may be viewed, then, as the imperishable elements of the body. This suggests that the geometric elements of the diagram correspond to the imperishable aspects of the Logos that uphold the perishable appearance of the Cosmos. These are none other than the imperishable layers of consciousness—which correspond to the universal gods.

The diagrammatic Tree of Life consists of thirty-two geometric elements: the ten sephiroth (spheres of splendor), represented by ten circles, and the twenty-two paths of wisdom, represented by twenty-two lines that connect the ten circles.

Fig. 4.1. The Tree of Life

The wisdom associated with this diagram relates to the “spine” of Adam Ouila. A spine may be compared to a ladder, with each vertebra corresponding to a rung. In this sense, the thirty-two elements on the Tree of Life may be compared to the first thirty-two layers above the half measure—that is, the rungs of the divine ladder that lead up to the station of the Creator.

Genesis tells us that God stands at the top of the divine ladder. With respect to the created universe, this God corresponds to the celestial godhead—the Creator of the universe—referred to in the tradition of kabbalah as Adam Ouila. This celestial godhead has the form of a sphere. The Hermetic texts tell us that the bodies of the celestial gods consist of only heads, and that a head means a “sphere.” The Vedic seers referred to this cosmic sphere as the cosmic egg (brahmanda).

In the tradition of kabbalah, the celestial godhead is represented by the Tree of Life taken as a whole. In the same way that the “head” rests upon the thirty-two vertebrae of the spine, so the whole of the Tree of Life rests upon its thirty-two parts. The celestial godhead corresponds to the implied thirty-third aspect of the diagram—the whole. Interestingly, in the Vedic tradition, the thirty-third layer above the half measure was viewed as upholding the “shell” (kapala) of the cosmic egg—but the Sanskrit term kapala (shell) also means “skull.” In this case, the thirty-two layers leading to the thirty-third layer may be compared to the thirty-two vertebrae of the cosmic spine, while the thirty-third layer may be compared to the cosmic skull that rests upon the spine.

As in the Hebrew tradition, there are certain doctrines in the Vedic tradition that give fundamental importance to the first thirty-two layers that uphold the created appearance of the universe. These layers constitute collectively the path of shakti—the path of analysis—which culminates in the realization of the thirty-third layer, viewed as the station of God, the Creator, the synthetic whole. The path of shakti may be compared to the path of subtle energy, up through the thirty-two vertebrae of the human spine, that eventually blossoms in the head. This presents another take on the ancient notion that humans were created in the image of the Creator.

Therefore, we find that the Vedic and Hebrew sages are largely in agreement regarding the imperishable layers that uphold the perishable appearance of creation. In both cases, the canonical set of layers can be summarized by the mystical formula

32 + 1 = 33

The thirty-two aspects represent the thirty-two layers, which constitute the ascending path, while the thirty-third aspect represents the synthetic whole—the thirty-third layer, which constitutes the goal of the path.

This congruence between the Vedic and Hebrew traditions lends support to the notion that the created universe is upheld by a canonical set of thirty-three layers, both above and below. The question that remains is whether this understanding is genuinely scientific: Are we dealing with an actual science of the gods, or a mystical form of religious theology?

THE EVALUATION PROBLEM

The validity of a scientific theory rests upon its ability to make accurate empirical predictions. Whatever its assumptions or models, the validity of a theory will be determined by its predictive ability.

The Vedic and Hebrew sages may have expressed their theories of the universe using mystical formulas and diagrams conceived on the basis of a completely different paradigm from that used in modern science, but this does not necessarily mean that their theories were nonscientific. Just as the mathematical formulas of modern theorists must be interpreted in order to assign them empirical meaning, so the mystical formulas of the ancient sages must be interpreted.

Our interpretation of the mystical formula 32 + 1 = 33 suggests that it pertains to the first thirty-three layers above and below the half measure, which form collectively the spectrum of creation. On the basis of the universal rule of thumb derived from the ancient teachings, we can assign these layers characteristic scales expressed in terms of centimeters. This amounts to an empirical interpretation of the formula. The ancient theory suggests that the thirty-three layers above and below represent the limits of creation. This can be interpreted to mean that they represent the largest and smallest distance scales that have any direct empirical relevance. The system of matched pairs predicts that these limits are on the order of 2 × 1032 centimeters and 2 × 10-33 centimeters, respectively. Given the fact that the ancient system is approximate, these are rough estimates. If they’re accurate, however, then the spectrum of creation is huge. The theory suggests that the largest span of creation is on the order of some three hundred trillion light-years, while the smallest span is some twenty-five orders of magnitude smaller than the radius of an atom.

In both cases, these estimates fall outside the range of direct empirical observation. There is no telescope or microscope that can fathom these scales. So how can we possibly evaluate the system using empirical methods? We are faced with a serious evaluation problem.

THE SUPERUNIFICATION SCALE

It turns out that modern theorists are faced with a similar problem. In order to construct a unified theory, it must be formulated on the smallest scale of space and time in the universe that is empirically relevant. This is called the scale of superunification—the scale where all the laws of nature become superunified.

The problem is that this scale cannot be observed empirically, even in principle; it can only be estimated on the basis of logical inference. The general consensus is that the unification scale corresponds to the Planck scale, which is now considered the most important scale in all of physics. It was derived originally at the turn of the twentieth century by a German physicist named Max Planck, who used dimensional analysis of what are arguably the three most important constants in physics:

- Newton’s constant, which governs the strength of gravitational force

- Planck’s constant, which governs the quantifying of all force and matter fields

- The constant speed of light, which governs the speed of all quantum waves

Planck found that these three constants could be arranged algebraically to define a fundamental distance, time, and mass scale. The problem is that the Planck scale represents an incredibly small time and distance scale that lies far beyond the reach of empirical observation. Due to its nonempirical nature, for many years it was viewed as nothing more than a figment of Planck’s imagination—a purely hypothetical scale derived from the units of the fundamental constants. Few theorists took it very seriously.

As they began to search for a unified theory, however, the importance of the Planck scale became more widely recognized. It is now considered the most important scale in physics; any new, unified theory must be formulated to it. More specifically, it represents the scale by which all the fields of force and matter are predicted to assume the form of a single unified field, which represents the source of creation. It follows that the Planck scale may be viewed as the characteristic scale of the Creator below. In other words, it represents the microscopic limit of creation. The ancient science of the gods predicts that the microscopic limit of creation corresponds to the characteristic scale of the thirty-third layer below the half measure. The system of matched pairs provides an estimate of this scale as of 2 × 10-33 centimeters. By comparison, the Planck length is predicted to be 1.616 × 10-33 centimeters. The two predictions, derived on the basis of very different theoretical paradigms, agree to within a factor of 1.

This is our first real indication that the ancient system of matched pairs might be genuinely scientific. At this point, however, the jury is still out. One numerical correspondence, taken by itself, does not make a scientific theory. Further, there is still a problem regarding the predicted macroscopic limit, which is estimated to be 2 × 1032 centimeters—a distance that spans hundreds of trillions of light-years. This is much larger than any cosmological scale conceived in modern theory. As a result, there is no theoretical support in modern science for upper scale, which the ancients conceived as the station of the Creator above.

In order to evaluate fully the scientific validity of the ancient theory, we still have a great deal of work to do. Approaching the problem in a systematic manner, we can start from the beginning—from the scale of the half measure—and examine the most important matched pairs in the spectrum as outlined by the ancient science of the gods. To do this, we must consider the various wisdoms regarding the gods.

THE SCIENTIFIC WISDOMS

In many ancient traditions, the gods were viewed as organized into sets or groups that serve collectively to uphold various levels and forms of creation. In the Vedic tradition, the doctrines pertaining to the groups of gods were called vidyas, a Sanskrit term that means both “science” and “wisdom.”

The ancient wisdoms are not easy to understand. At first glance, they appear extremely confusing and even contradictory. The problem is that each wisdom purports to present a picture of the whole—yet the number of gods, categories, layers, and so forth involved in the various wisdoms differ widely. From the perspective of the modern mind, which seeks a conclusive, well-defined model of reality, it would seem natural to presume that the ancients were in disagreement—but this would be a mistake. The ancients possessed an enlightened vision of the universe, which was highly subjective, allowing for complementary perspectives on the same idea. This notion is reflected by the Vedic aphorism, “The truth is only One, though the wise may speak about it differently.”

Enlightened vision, however, is also holographic. A hologram is a record of coherent light, which can be used to project a three-dimensional image. Unique to a hologram is that the same image can be projected from every part of the record. The larger the part, the higher the resolution of the projected image; the smaller the part, the lower the resolution—yet in every case, the same three-dimensional image can be projected. The spectrum of layers may be compared to a cosmic hologram on the basis of which a three-dimensional image of the universe is projected in consciousness. In this case, the layers correspond to the parts of the hologram. As the enlightened soul ascends through the layers, it grasps larger parts of the cosmic hologram, corresponding to larger sets of layers. As a result, the projected image of the universe increases in resolution, but the same universal image is seen no matter how large a part of the cosmic hologram is grasped.

When the soul begins its journey, it tends to cognize a low-resolution picture of the whole, and at the end of its journey, it cognizes a very high-resolution picture. Yet the same universal image—the same whole—is cognized at every stage. The ancient wisdoms relate to these different holistic pictures of the universe obtained on the basis of different sets of layers. They were formulated in terms of different numbers of gods, categories, worlds, and so forth. As such, they are confusing to us and were also confusing to the ancient students of those wisdoms. For example, in one Vedic text, a discourse is presented between an inquiring student and his teacher. Bewildered by the various opinions of the sages regarding the number of worlds, gods, and categories, the student asks: “With what intention do the sages severally declare such a large variety of numbers?” The teacher replies:

The categories being comprised in one another, O jewel among men, are enumerated as more or less according to the subjective viewpoint of the speaker. In a single category, whether it is viewed as a cause or an effect, are found all the other categories. Therefore, we accept as conclusive whatever is stated by those sages, according to their own subjective viewpoint, who are seeking to establish a cause-effect relation, or a definite number of categories, there being a cogent reason behind every such assertion.5

The fact is that the ancient science was subjective; it was rooted in various subjective viewpoints on the reality of the universe, and each of those viewpoints was tied to a particular scale, or set of scales, of space and time. The wisdom pertaining to one set of scales may be different from that pertaining to another set, but in every case the wisdom was holistic.

In the remainder of this book, we will examine a number of the most fundamental wisdoms outlined in the Vedic, Egyptian, and Hebrew traditions—each of which utilized its own symbols, metaphors, models, and allegories. In the process, we will discover that when understood, the ancient wisdoms are very scientific. They accurately predict a hidden vertical symmetry in the overall organization of the universe, which is currently unknown in modern theory, but is nevertheless consistent with the empirical evidence. To begin, we shall start with the first wisdom, which has to do with the origin of the universe at the very beginning.