THIRTEEN

The clatter of the doorbell in the downstairs kitchen that evening announced company: Thérèse Chevalier. She’d seen my light the night before from her house across the hill from Mme. Vera’s, and since she was off to her apartment in Paris the next morning, she had come up to say hello.

Black clouds had frisked across the sun and stayed there late in the afternoon and, after deliberating and waning, had spread to deliver a steady drizzle. Thérèse wore boots and a yellow slicker and carried an umbrella, having walked across the fields between her house and mine.

Thérèse was of the generation poised between mine and my parents’, just as her own parents fell squarely between my parents and grandparents. She had spent much of her childhood in Mesnil. She and her mother (her father was then at sea) had been among those who walked from Paris into the countryside under a rain of German bullets as the French capitulated to the Germans in June of 1940. They were in Caen when it was bombed by the allies in June of 1944, and they walked from the flaming ruins of that city to Mesnil while the D-day invasion was in progress. On her mother’s side, Thérèse was a member of the extensive Lafontaine family, which descended on Mesnil every August from its varied winter quarters elsewhere in France and North Africa, historically making up half the town’s summer population. She was unmarried, funny, charming, and intelligent; a former teacher of history at a French university, she spoke perfect English. For several years she had been what she called retired, but I had never known anyone more in love with her profession. She had turned history into her hobby now that she was no longer teaching—but she hadn’t really stopped teaching, either, since she was always on the lookout for a new student. Thérèse, like the ancient mariner, loved nothing better than to hold you with her glittering eye and reveal to you her most recent cache of research. I knew what was coming.

Thérèse left her wet things in the downstairs kitchen and followed me upstairs for a cup of tea next to the fire. We sometimes went years without seeing each other, though we had the familiarity common to siblings widely separated by age. She looked around approvingly at my informal arrangements in the dining room, particularly the books that were piling up on every available surface.

“Good to see you settling in,” Thérèse said. She was not one of those visitors who muttered, shook their heads, and said something along the lines of O, what a noble house is here o’erthrown, though she had known it when my grandparents lived here, at which time it had indeed been more finished, furnished, and coherent. For one thing, it had not yet been vandalized for heat then: the refugees had burned bookshelves, paneling, and closet doors, as well as furniture. But nonetheless, even in my grandparents’ day, the effect had been threadbare and eclectic (or as Saint-Gaudens more tactfully put it, “completely colorful”). My grandfather, always a domestic painter, had preferred to work in the house, and many of the paintings he did after 1920 showed furnishings we could still point to. My grandmother would rush about the house second-guessing and sweeping surfaces before him as he roamed in search of a subject or vantage point; she hoped to prevent him from recording as still-life what to her eyes (and, she believed, to anyone else’s) looked like clutter that would shame her as a housekeeper when the resulting paintings were hung at the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux Arts in Paris, or at Macbeth’s gallery in New York.

The salon with Mrs. Frieseke, 1937. Photo Claude Giraud

“But the gardens were something else,” Thérèse said. “There was nothing neglected about your grandmother’s gardens. Oh, the stories she would tell. Mae West, and Buffalo Bill, and bandits in New Mexico; and how she would dress everyone in costume for a birthday or a fête. She was so much fun. Such a shame your grandfather never learned French. I followed him in the field while he was painting, and he never said a word.”

In fact, my grandfather knew French perfectly well, but as it was explained to me, he did not speak if he had nothing to say. My grandmother, in contrast, like Julia, was a gregarious, compelling, adept, and entertaining talker who was sometimes obliged on social occasions to make do for the two of them.

Thérèse and I sat on either side of the fireplace and listened to the rain splash against the slates and occasionally find its way down the chimney in drops large enough to hiss on the embers. We ran through recent family news as the tea steeped, covering the necessary groundwork while Thérèse clearly itched to include me in her present obsession—or obsessions (plural), it turned out.

The following day, she must rush off to Paris for her regular session with the life models whom the government made available to the citizens of Paris. She was drawing and painting seriously now. Then she must hurry back as soon as she could to Normandy to continue gathering bits of research that would connect Mesnil and its environs to the larger picture.

She dropped three lumps of sugar into her tea and stirred—paused—and let the full joy of her project start to unfold.

“My idea is a history of Mesnil, starting in the Cretaceous period, when we were all underwater here where we are sitting, and the animals were laying down their chalk shells to make this hill. Then I’ll move slowly forward to the present day, always with Mesnil as the focus—but I don’t know, what do you think? Does it matter that there are only about thirty people at any given time in Mesnil who might be able to read it, or want to? But it could be great. Some interesting people have been here. Charles Gounod, of course, the composer who wrote the ‘Ave Maria’; everyone knows he was an important character around here. You’ve probably heard a thousand times how he met the Count of Mesnil while walking on the beach in Trouville in 1846, and they became friends for life. Gounod had almost drowned—he was older; the count was just a kid at the time, twelve, at the beach with the priest who was also his tutor. So there’s Gounod. But there were others, too.

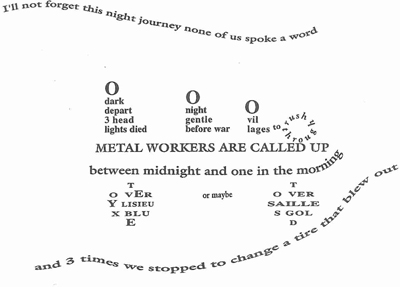

“You know Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet? Right on the first day of the First World War, he was so near your house you could have thrown a rock and hit him.” Thérèse seemed to be looking into the fireplace for a rock of the right size; one of the fossilized clamshells from the hill would be about right. “He’d been in Deauville with a friend and because of the mobilization they had to drive back to Paris to enlist, which they did via the road that goes through Pont l’Evêque and Lisieux. He had a flat tire near here, which he made famous in a poem he wrote in the shape of a little car—look, I’ll show you—with a driver and two passengers.”

She pulled a Xeroxed page out of her bag.

“August first 1914,” Thérèse said. “The day France declared general mobilization against Germany.”

If it was history she was after, I had something to toss in. I told her how my mother had also responded to the mobilization call as best she could, though she was a day late: she was born in Paris on August 2, 1914.

We talked of how the illustrated newspapers from the period just before that war read as if everyone believed that all the armaments and uniforms were being prepared for a parade of limited and specified duration and direction. Although many of the Americans residing in France left just before or during the onset of the war, the Friesekes had remained, in Paris and in Giverny, where the sounds of cannon fire had interrupted my grandfather’s painting by making his models jump.

The Friesekes with the Ford.

The Friesekes had no car then, and would not until the Ford and Georges the chauffeur. My grandfather did attempt some patriotic driving for the Red Cross ambulance service during the hostilities, but it wasn’t long before everyone acknowledged that he endangered more than just the wounded whenever he got behind the wheel: always drawn by landscape, he tended to follow his eye. He was transferred to bedpan duty and rather quickly went back to painting.

* * *

The evening darkened outside, and the rain intensified. I had always wanted to ask Thérèse about some of her father’s stories. During the first years of our visits, Alain Chevalier had been generous with his time, driving us here and there and telling us stories.

During the Second World War, after he came back from the sea, Alain had told us, when the house Thérèse and I now sat in was occupied by the Germans, he had kept a clandestine radio at his house in Mesnil, using, for an aerial, a metal clothesline. What did Thérèse remember of this?

Thérèse looked blank and slightly uncomfortable, as if the specifics of her father’s tale had some negative impact on her view of the big picture. She dodged. There was so much war, she said, in the region’s history. After the Romans, and following several centuries of something like peace (albeit a chaotic and dangerous one), Viking river boats of shallow draft, like the flatboats or gabarres used by local traders, had penetrated the land of the Pays d’Auge by way of the River Touques, which meandered northward through broad marshes and welcomed the raiders at its mouth, emptying into what English-speakers called the English Channel at what was now Deauville. In 1944 the German forces of occupation had manned a large gun emplacement in the same spot, overlooking what French maps used to refer to as Le Canal de France but now termed La Manche (the sleeve). That battery had been part of the defense of the Seine estuary, across from Le Havre.

“But your father?” I pressed her.

As far as what her father had done during the war … Thérèse could not recall anything about a secret radio in Mesnil.

“During the war,” I continued, “at the time of the D-day invasion, when the bombing was widespread—I’ve heard that forty bombs fell just in this commune—the citizens of Mesnil, with their cows, according to your father, took refuge in a cave in the hill across the valley.…”

Thérèse looked more uncomfortable. Even seated next to the fireplace she was tall, and she was sweet, with her father’s warmth and wit. But she was also as pious and as devoted to the truth as had been her mother before her. She said, “You know, my father … unfortunately, my father really enjoyed a good story.”