NINETEEN

A telephone call from Margaret startled me out of my task. They were ahead of schedule and promised to be with me in time for lunch. I now had to drive to town and get supplies for lunch, and dinner, before everything closed.

On my way into Pont l’Evêque, I remembered the spectacle of Margaret and Julia at the sink. I had not yet tested the washing machine to see if it still worked. Sheets: I would have to lay out linen.

In Pont l’Evêque I noticed it was Sunday. Church bells banged in the rain and the streets bustled with crowds shopping for their noon dinner, which in these parts on a Sunday was a very serious affair. While shopping, I was conscious for the first time—no doubt because I was thinking in a proprietary way of the glimpse of “Old World charm” I was going to be able to offer Margaret and Ben—of the many rain-streaked posters in Pont l’Evêque in which persons of youth, nudity, and some beauty were exhibiting their sneakers. I realized how much during the time I had known the town, the provincial purity of the place had been dissipated by the incursion of urban culture. When we first came to Pont l’Evêque, there were no public images of undraped humans beyond a diagram in the window of the pharmacie having to do with trusses. Pont l’Evêque was, after all, the birthplace of Flaubert’s mother and home of the same writer’s blameless character Félicité, in Un coeur simple. No more than ten miles from the excesses of the beach at Deauville, it had nonetheless seemed a lifetime away; and Deauville was not yet a topless beach in 1968, nor would it be until long after the revolution.

Because of the rain, my car had to struggle for traction on the driveway coming home. Now one could stand in steady, declining mist and watch the approach of serious rain squalls, walking on wide legs between which might float snatches of clear sky as blue as the eye of God—but always somewhere else, across the valley. Normandy was Normandy again, a country made of rain. When the hill the house was on dried out during the summerlong drought of 1976, apple trees simply fell over because the earth they had stood in, having lost so much of its bulk (in the form of moisture), could no longer hold their roots. There was nothing to keep the orchards from giving in to gravity.

I stowed the groceries and surveyed the wreck that fate and I had been collaborating on in the situation room, formerly the dining room. In time for lunch, Margaret had said—so I’d take that as permission not to lay on a heavy spread at noon, as everyone else in Normandy was doing. That would give me time to hide the evidence of odd jobs and to get the place looking as good as possible. I wanted to do this partly because nobody could use the upstairs bathroom in its present state without risking sudden death, but mostly because I knew that Margaret and Julia had no secrets from each other, ever, and there was no way Julia was not going to be talking at length with Margaret about my situation—and before I got home. I had already noted a tendency among women to agree on the (lack of) wisdom of taking on a second home in a foreign land: the men would always encourage, while the women would immediately and instinctively pull the long faces that might greet the news that we were about to have unexpected triplets on purpose now that our youngest was sixteen. Women’s sticking together, I complained to myself, is the curse that forms the cornerstone of civilization. And you can’t fool them, which is another way of saying the same thing. But you have to try, which accounts for the origin of language.

I rushed to find and hang curtains in the upstairs bedrooms—the fruit of a whole summer’s labor on the part of Julia, my mother, Julia’s mother, and assorted others—and then to reinforce the catwalk across the bathroom floor (Ben was a large and heavy man). I dusted the tops of furniture and put cloths across the most Victorian pieces from the O’Bryan line.

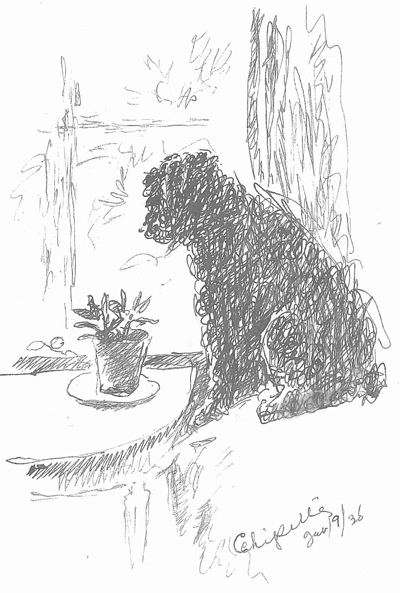

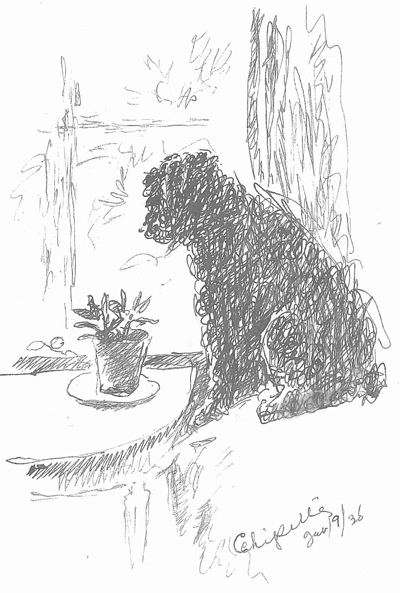

I heard my guests before I saw them, and saw them long before they managed to get their car to the top of the muddy slope. That gave me time to open the water main. The first out of the car was one I hadn’t expected: Andalouse, a large unreconstructed French poodle of urban tastes who sniffed the falling air; declined to take in the riot of new experiences available to any dog arriving on a farm; refused even to acknowledge the frenzied greetings from Mme. Vera’s yard; and instead stalked inside to seek out remnants of the scent of my mother’s childhood pet, Chipette, also a poodle. Ben climbed out, loudly congratulating himself on getting the car up the hill, and then Teddy, whose head, since it reached almost to seven feet, I saw immediately would be in constant danger from ceiling beams and lintels, and then Margaret. All wore sweaters and jeans and hats of one kind or another: they were fresh from a wet Channel crossing, and voluble about it.

Chipette, ink drawing, F. C. Frieseke sketch book, 1936.

Margaret stood in the rain grinning, and said into the car, to Ruth—the fifth member of their party—“I told you, just like Holland, except it’s not flat, there’s more rain, and everyone talks French except our host.”

* * *

“We haven’t come all the way to Normandy to take a nap,” Ben said after lunch, as we gazed out the dining room’s west window, overlooking the valley, at some little birds that I didn’t remember from previous visits. They had been there for two days now, jerking up and down as if on strings, parallel to the slates on that face of the building; they seemed to be plucking out of the rain insects issuing either from the wall or from the auvent beneath the window. There was something both charming and worrying about the show, and Ben reinforced the latter quality by asking idly, “What’s that they’re eating? Termites?”

I’d looked up these birds earlier, while I was deliberating about my owl, and had decided they were a species of bergeronnettes, yellow wagtails. I wondered myself what they were eating, inasmuch as it (or they) seemed to be coming out of the walls. As the resident expert, I must speak.

“The book says they eat flies,” I temporized.

“Houseflies—that would make sense, coming out of the house,” Ben said. “Anyway, I admit the weather’s perfect for it, and I’m probably going to want to take a hundred naps while I’m here, but why don’t we do something else today?”

Teddy and Ruth were knocking around the half-kitchen, doing the dishes. Teddy could barely make it under the ceiling beams without ducking. It turned out he was a paleontological biologist by trade. Ruth, closer to me in age than was Margaret, was rather small and energetic, almost haunted in appearance, and, I learned, labored under the cloud of an uncompleted Ph.D. thesis in anthropology, concerned with methods used to date the ancient human-worked flints that could be found in certain parts of Italy. Hearing this, I looked on her with an eye lustful with speculation, since the hill we were on was rich in flint, which often looked worked. Many a child of mine had returned to the house carrying a flint that either contained a fossil (or something that might become one given enough time or argument) or seemed likely once to have been used to skin a Neanderthal boar.

Ruth and Teddy discussed England and the English as Margaret kibitzed through the opening between dining room and kitchen, which under the present regime allowed diners and servants (who were now interchangeable) to converse and help each other.

“They’re barbarians. That food! Wherever you go, the English try to give you a first course that’s either a bad tomato or half an avocado stuffed with little canned shrimp in mayonnaise,” Teddy was complaining.

“And you ask why England has remained an island!” Margaret proclaimed rhetorically. Her observations were often right on target, but they sometimes got her into trouble.

“I am now going to change into my warm clothes, which I am glad everyone warned me to bring,” Ben said. “And then let’s do something. Hit the beaches or whatever. According to the map, we’re only about a dozen miles from Sword Beach.”

“Get in the car and I’ll show you around,” I said. “I’ll point out the way to the D-day beaches, and you can go there on your own later.”

I drove my car, with Ben and the women in back and Teddy telescoped in beside me. Andalouse needed no persuasion to stay by the banked fire. I advised my passengers that they might have to walk when it came time for us to ascend the drive again.

Our road north toward Pont l’Evêque paralleled the railroad line along a short segment of the Vikings’ river route through the Pays d’Auge, the valley of the Touques. From the backseat, Ruth informed us that this was the northwestern border of a carboniferous limestone deposit laid down in the secondary era in the region known broadly as Sedimentary Normandy—or, more euphoniously, since the Seine emptied through it, the Paris Basin. The exposed raised rock of Brittany was older, she said; granites and crystalline rocks made up the Armorican massif, whose northernmost protuberance, the Cotentin Peninsula, had been joined to southern England and Nova Scotia before those masses drifted off on their own—England because it insisted on serving avocado with prawns, and Nova Scotia perhaps to get as far as it could from England’s diet. The Armorican massif, to the west of us, had formed a dike during the tertiary, when twice the Paris Basin had been flooded by shallow seas or lakes. The inhabitants of those waters had left chalk deposits hundreds of feet thick, above which were the flints generated by the decomposition of rock during the period of equatorial climate that preceded glaciation. Or so Ruth told us.

Perhaps Ruth should do the opening chapter of Thérèse’s history of Mesnil, I thought. And Teddy could add a note concerning the area’s ancient flora, the oldest surviving example of which was equisetum, or horsetail (a plant that looked as if it had been invented by Dr. Seuss), of which Teddy had already pointed out two species—one specializing in the field, and the other in marshy ground.

The hills rose on either side of the Touques Valley, all that was left of what had been a plateau of ancient ocean floor: islands of pasture, orchard, and woodland reaching as high as six hundred feet above what was now sea level, to which the myriad persistent rivers, streams, brooks, douets, and becs separating the peaks had washed their flinty beds.

“According to a friend of mine, Thérèse,” I told them, “greatness has passed before us on this road. Louis XVI himself, in June of 1786, with a large and expensive retinue, followed this road. You must imagine the local folk filling the ditches with shouts of vive le roi, and now and then a brave farm wife rushing forward to kiss the hem of his carriage. The trip was sudden, and there’d been a frantic rebuilding of bridges and reinforcing of roadbeds. Louis was returning from the inspection of some absurd and absurdly expensive sunken fortifications he was building at Cherbourg against the English navy. He was heading, via Pont l’Evêque, for Honfleur and his beheading seven years later. Thérèse says Louis was warned before his trip, by his advance man, that because the Pays d’Auge country was remote, and its commerce required little in the way of cartage, he’d find many roads unfinished.”

In fact they were still working on the stretch near Manneville.

We motored past fields and were still in fields when the town began. I drove my guests through Pont l’Evêque, dismissed by Louis XVI’s scout as follows, “This little town has nothing remarkable.” I tried for a tour that would mingle the historical with the practical, while mentioning items (such as Guillaume Apollinaire’s flat tire) that should interest any tourist. The town stands at a confluence of rivers through or among or across which the Bishop (évêque) of Lisieux, within whose diocese the region fell, was said to have built a toll bridge (or pont—whose proceeds went, of course, to the bishop benefactor), during the eleventh century. I found it difficult to believe that the Romans did not have their own bridges long before that, but perhaps they made use of ferries. They could have collected their own tolls on those just as well.

Pont l’Evêque’s coat of arms boasts two gold oxen on a red field. One rumor claims that the town’s name had humbler origins as Pont-à-la-Vache, or Cowsbridge, easy enough to upgrade in French to Pont l’Evêque, or Bishopsbridge. The name does not turn up in the written record until 1077, the year Hugh, Bishop of Lisieux by right of consanguinity with William the Conqueror’s family, collapsed on the road not far from where Apollinaire had his flat, in Ouilly le Vicomte. A ouille was a wine barrel in old French; in those days they still struggled to grow the grape in Normandy.

Lisieux had once been a walled and fortified city, but as Thérèse had told me, it was hard to credit Pont l’Evêque with the same. It sat on a broad, flat, marshy plain riddled with rivers: the Touques, the Calonne (which emptied into the Touques just north of the town), and the Yvie. I showed my passengers how the smaller, less trafficked of the roads from Lisieux toward the coast met Pont l’Evêque’s main street, fumbled to maintain its direction, lasted another block, and finished abruptly in back of the jail and the glass-recycling bin, in a parking lot next to a long-unused covered lavoir that the Syndicat d’Initiative kept up as a monument to happy bygone times when women knelt and scrubbed. The other road, I explained, continued north from Pont l’Evêque and branched off to meet the coast at Honfleur and Deauville; that was the route along which Guillaume Apollinaire had driven, the route that Henry V’s brother Clarence had followed on his way to take Lisieux, the route that Lindbergh had later used as a map to guide him toward Paris from the coast, and that Louis XVI followed in the opposite direction, on his triumphal march.

Pont l’Evêque, having suffered its most recent truly serious battering in the religious wars of 1590 and having remained architecturally tranquil for the next 350 years, was practically obliterated during the liberation of 1944. Most of what was to be seen in Pont l’Evêque was therefore modern, apart from some sixteenth- or seventeenth-century remains. When the smoke cleared after the battle of Pont l’Evêque in August 1944, the thirteenth-century limestone church of Saint Michel was still standing, though it had lost its spire and all its glass. At the western end of the town (closest to Caen, the birthplace of Charlotte Corday), where some half-timbered sixteenth-century buildings had escaped the bombing, we got out of the car to wander. Swallows nesting in their crevices darted among the old houses and snatched insects from the streams and small canals they overhung. I pointed out one of the practical functions of the picturesque Renaissance style in which the second story juts out beyond the first: here, as elsewhere, these remnants of the style ancien had privy holes cut in the floor over the water.

Its being Sunday afternoon, and after lunch, and raining, Pont l’Evêque sagged in replete stupor. Shops that had flourished for trade that morning now looked abandoned and belligerently for sale. That would change the next day, I explained: Monday was market day.

I showed them Pont l’Evêque’s hospital, the pharmacy, a shop where one could find a newspaper and another where one could not, two quincailleries (for hardware and bottled gas), a droguerie (for dry goods such as toilet paper, brooms, paint, steel wool, brushes of all sorts, turpentine to fill any bottle the customer supplied, mirrors, and toothbrushes), four bakeries, three charcuteries (for prepared meats or such cold dishes as celeriac or deviled eggs or crushed ham forced to look like a partridge, as well as cuts of meat whose country of origin was the pig), a shop for furniture, a shop for saddles, a shop for cloth, one for calvados, one for boots and shoes, another for clothes, three butchers, and two all-purpose grocery stores. Everything was closed up tight.

Ben, a generous and impulsive shopper when it came to supplying a friend’s table, made impatient noises from the backseat. “Everything’s closed! What about cheese?” he asked. “Aren’t they supposed to have cheese?”

There was no shop for cheese alone, but I showed them a charcuterie where the next day, if they conferred with Madame, she would select for them a Pont l’Evêque (the cheese for which the town had been famous since the thirteenth century, though it used to be called Augelette) that would be ready to eat either then and there or on some future day of their choice. They could follow her progress and her muttering commentary as she tested each one with her thumb.

“If your will is perfection as well as conversation, that is the way to shop, as you know. I know that,” Ben affirmed. “You say market day is tomorrow? We’ll come in tomorrow and buy everything. Cheese and whatever else you want, we’ll buy it, and maybe some other things as well.”