SEVEN

Our practice, when the house was vacated at the end of summer, was to have the rugs rolled and the curtains folded and put away. Once light was admitted, the rooms had a dejected air, needing more color and feel of habitation than were provided by the paintings of mine I kept on the walls. Until a fire could be lit in the dining-room fireplace, that dependable source of heat and comfort was simply big and black—and all in all, the inside of the house was a grim contrast to the belligerent and fecund wallops of green and sky that shoved against opposite sides of the room, from the door and window into the garden on one side, and from the window overlooking the valley on the other, where the sun would set in about eight hours.

The dining-room ceiling, like those of the other rooms on this floor, was low—about seven and a half feet. The walls were made of plaster grooved to look like laid stone, and had once been painted accordingly; the ceiling, meanwhile, had been allowed to go black with smoke. After we painted everything white or cream, with the woodwork and window casements a subdued but nevertheless defiant yellow, Julia had announced, “It looks less like a tunnel.” But having been empty so long, the room seemed derelict now, even when stroked by hot daylight from outside. Rugs could wait, and curtains, but the place must have color as well as light, and some dry air. It demanded color the same way a slow brown meal cries out for salad.

While my tea steeped, I threw one of the cloths that Julia had sent with me across the dining table, which wanted to seat ten serious diners. The cloth had bright-red and white stripes. When I sat down, I realized something was missing. The large round wicker tray that should be tucked into its metal rail along the wall, next to my place at the table, was gone. This one missing thing gave me a sensation of disquiet worse than that occasioned by the lack of running water. We’d never used the tray, but for me it preserved the illusion of that uneasy “era of tranquility” that Homer Saint-Gaudens had written about, which he located within the brackets of the Great Depression on one side and the Second World War on the other. I had photographs of my grandparents having tea with friends, using this tray and seated not twenty feet away from where I now sat. Nobody in these photos was dressed for the countryside—that is, not for field work; everyone wore a suit or a nice dress, and a hat of absurd elegance, for all that the nearest cow flop might be no more than seventeen feet away, on the other side of the white gate. You could almost hear the ancestors of Mme. Vera’s chickens gibbering. That era was lost to me, it was true, but at least I’d always had the tray.

That tray belonged here. It was part of the package. Measuring some three feet across, it would be hard for a renter to hide or misplace or carry home in a suitcase. It was above all an emblem of the house, having survived unscathed and unmoved throughout the whole war, being almost the only thing that was still where it should be when we returned in 1968. Back then, my mother had taken its continued presence in the wreck as a good omen; now, its absence prompted in me a nagging awareness of disproportion that made it impossible to sit still for wondering what else was missing or awry. What had the O’Banyons done with the tray? Or had someone else been in here during the winter? I looked around.

Tea outdoors, 1924. (Left to right, Mrs. Hoeveler, Stellita Stapleton, Mrs. Stapleton, Edith Frieseke [Aunt Dithie], Frances Frieseke, Mahdah Reddin, Germaine Pinchon, Mme. Pinchon [seated]).

Not much in the dining room could be mislaid. The table was so large and square and the floor so uneven that there was only one place in the room that it could go, and even so, when diners were numerous, somebody had to compete with one of the posts that held the ceiling up. The other furniture, aside from the chairs, was similarly cumbersome: a contemporary couch that could become a bed, and one and a half wooden armoires to hold china and necessaries. Against one wall was the masonry sideboard on which in the old days dishes could be kept hot over pans of charcoal. Now it housed the telephone.

With all its doors, shutters, and windows open, the dining room had become inhabited by the voices of birds that were not yet aware that anyone was here. A blackbird sang from one of the fruit trees in the garden’s second terrace, which was now striving to become woods again. I followed the sound of one of the fat black flies that had no business in the house, but entered by the garden door and paraded directly through its shade in a distracted beeline to pass out the casement window next to me. It buzzed over the absent wicker tray and into the bright trough of the valley, looking for a cow’s wet muzzle or dropping to belabor.

That busy industry of flies, like the cries of the wood doves and the scent of box from the garden side of the house, and grass and cows from the other side—if all those were right, nothing else could be that far wrong. As long as I was here, I decided, I would not camp out after all but would allow myself to open the rest of the rooms on this floor, and live at least that civilized.

As I moved through the rooms, I forced myself not to look for the tray, knowing that could lead only to the serendipitous discovery of other missing links to lost causes. Instead, I pretended to put the tray out of my mind, along with some of the other, more complex questions I would have to entertain while I was here, such as what to do about the kitchen(s).

Next to the dining room, and south of it, was the library, where I would sleep; then, reading northward from the dining room, the half-kitchen, the salon, and the bath and guest rooms, all of which I resolved to open. The remaining space on this floor, next to the central staircase leading up to the next floor, was taken up by the jam closet, which I would not open for as many years as I could put it off.

In my grandparents’ day, the library had been a library. There was no bed in it then as there was now, but the same desk sat at the same perpendicular to the window overlooking the driveway; here my grandmother wrote letters and, when she stood, jostled her husband’s wicker fishing creel, which hung on one of the room’s two supporting posts. Often my grandfather read there while my grandmother sewed or knitted (her generation kept its hands busy). Sitting at that desk to read, an occupation that he favored over painting, my grandfather could see when a visitor came up the driveway, giving him plenty of time to be out the door and into the woods with his book before the knock on the door. He had begun collecting books as a boy in Owosso, buying Horatio Algers from a peddler until his grandmother weaned him onto Dickens’s Oliver Twist, assuring him it was another rags-to-riches story.

After-dinner coffee might be taken in this room, and sometimes there was a painting in progress here, with my grandmother reading aloud if my mother was posing. The smell of the dining room, reaching into the library, was dominated now by the acrid aura of the former’s big damp chimney and its bed of ashes, left behind last fall to foster the initial fire of summer. That staleness I would easily fix tonight by making a fresh fire. I brought my bags up and took possession of the library.

Then I opened the salon, a room elevated by Mayor Isidor Mesnier to this Parisian level from the mere salle it would have been in an honest farmhouse. I passed through its circle of variegated chairs, its sifting bouquets of dried flowers, its little ornamental tables giving in, in different ways, to woodworm and gravity. The salon had once been papered with the Bay of Naples; it still felt damp, though the bay itself had washed away after the war. Nothing untoward met my eye on this first glance, except that all felt damper and colder than I remembered. I noticed mold growing on one of my paintings of the Douet Margot, which was as close as the salon now got to the Bay of Naples. I threw open the garden door.

After Frances married, in 1937, and moved away (“I didn’t think you were that kind of girl,” her surprised and dejected father said), my lonesome grandparents had photographs taken of the house to comfort the young bride should she become homesick amid the excitement of her new life. From those photographs, and from paintings that Frieseke did in this room, I was familiar with the formal and rather eccentric nineteenth-century look it had then, of which almost nothing remained now.

I checked that the huge bathroom next to the salon had cold water. At some point in the future I might go outside to instigate its hot water. The toilet’s tank, up against the ceiling, chuckled and screamed as it always did when it filled, loudly enough to waken, if not the dead, then at least anyone who inhabited the guest room next door. (That charming little paneled room, the same size as the bathroom, tended, despite its fireplace, to be the dampest room in the house.) The loose tiles in the bathroom floor were no more numerous or looser than I remembered. The permanent spiderweb in the exact center of the cold radiator under the bathroom window overlooking Mme. Vera’s was tenanted, as it should be, by this year’s large black spider, which, if I killed it, would be replaced by morning by another exactly like it—one similar to, but different from, the one that always lived in the bathtub drain.

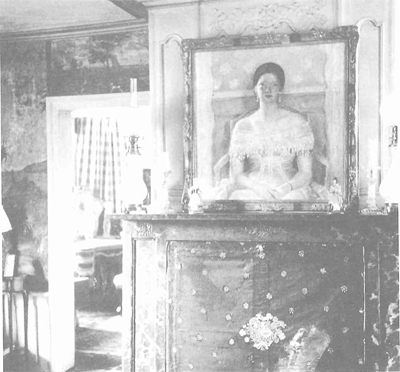

The salon, with Frieseke’s portrait of Frances, 1937. Photo Claude Giraud

Hovering just beneath the smell of the fireplace were the symphonic strains of plaster dust and damp and sifting particles of wood digested by the worms in the furniture; the varied dirts of woods and pastures, blown in under the doors; smoke; linen; mothballs when closets were opened; and old books. The house contained as great a volume of books as it did of torchis, the material used between the timbering. I had mentioned to Julia once, in our continuing argument, that one good reason for us to take on the ownership of all this was to avoid having to answer the question “If we don’t, what are we going to do with all those books?”

Aside from the missing tray, everything was as exactly familiar to me as a loose tooth the nerves and tongue have grown accustomed to. I opened the doors and shutters of each room and looked outside, knowing that when I called Julia, the first thing she would ask was, “Is it beautiful?” Then she would want to know what room I was sleeping in, aware that there were six possibilities—or seven, counting the couch in the dining room. And I would answer, as she knew I would, “The library,” because I wanted to be near the telephone in case she called. Anyway, there was no reason to go through the bother of opening the rooms upstairs.

She’d ask how the cloths she’d sent over looked. All but the red-and-white-striped one were still packed. You know, honey, for someone who’s resisting this move, you ought to notice that you’re adding to it, not subtracting—making it more to give up if we don’t do it, I mumbled or thought. Since I was alone, it didn’t much matter which.