The older I get, the more I realize it is not always what you say, but the way you say it. And that is particularly true in politics.

—HOTEL MAGNATE PENNY PRITZKER

Barack Obama’s first thoughts about running for the U.S. Senate came as early as mid-2001, less than a year after his stinging defeat by Bobby Rush. After that race, Obama had been approached about running for Illinois attorney general, but discarded the notion for the same reasons Dan Shomon warned him away from the Senate run. Said Obama, “I put Michelle and the family through such heck with the congressional race and it put such significant strains on our marriage that I could not just turn around and start running all over again, so I passed that by.”

Coincidentally, the thought of Obama running for the Senate had also occurred to Eric Adelstein, a Chicago-based media consultant for Democrats. Adelstein had scheduled a meeting with Obama for September 2001 to discuss their mutual idea. But little could either man have known what would transpire on September 11 of that year. “So 9/11 happens and immediately you have all these reports about the guy who did this thing is Osama Bin Laden,” Obama said. “Suddenly Adelstein’s interest in the meeting had diminished! We talked about it and he said that the name thing was really going to be a problem for me now. In fairness to Eric, I think at that point the notion that somebody named Barack Obama could win anything—it just seemed pretty dim.”

So Obama went back to concentrating on his two jobs as constitutional law instructor and state lawmaker. But by mid-2002, he again was growing restless in his political career. He began toying again with the idea of the Senate contest and he opened serious conversations with his Illinois senate colleagues about the notion. Several seemed receptive—Denny Jacobs, Terry Link, Larry Walsh and members of the black caucus, including senate president Emil Jones Jr. They promised to support him, even to lead an exploratory committee.

But there was one person whose affirmation was vital—Michelle. Convincing Michelle to support him through another campaign was the most significant hurdle Obama had to clear. Michelle knew that her husband’s political career was of immense importance to him, but upon hearing his Senate idea, she began to wonder if this optimistic dreamer was going off the deep edge. The couple had two kids, a mortgage and credit card debt. After Obama’s crushing loss to Bobby Rush, she worried that her husband was about to undertake another lost cause, although, realistically, she worried primarily about finances. Another political race could keep the family in debt, or perhaps plunge it deeper into debt. And even if he won the Senate seat, she thought, their financial condition was not likely to improve.

“The big issue around the Senate for me was, how on earth can we afford it?” Michelle told me. “I don’t like to talk about it, because people forget that his credit card was maxed out. How are we going to get by? Okay, now we’re going to have two households to fund, one here and one in Washington. We have law school debt, tuition to pay for the children. And we’re trying to save for college for the girls. . . . My thing is, is this just another gamble? It’s just killing us. My thing was, this is ridiculous, even if you do win, how are you going to afford this wonderful next step in your life? And he said, ‘Well, then, I’m going to write a book, a good book.’ And I’m thinking, ‘Snake eyes there, buddy. Just write a book, yeah, that’s right. Yep, yep, yep. And you’ll climb the beanstalk and come back down with the golden egg, Jack.’”

But Obama was confident that he was destined for more than just a day job running a foundation or practicing law or languishing in the minority party in the Illinois senate. And for that golden destiny to come to fruition, he knew he had to do his most convincing sales job yet.

Explained Obama, “What I told Michelle is that politics has been a huge strain on you, but I really think there is a strong possibility that I can win this race. Obviously I have devoted a lot of my life to public service and I think that I can make a huge difference here if I won the U.S. Senate race. I said to her that if you are willing to go with me on this ride and if it doesn’t work out, then I will step out of politics. . . . I think that Michelle felt as if I was sincere. I think she had come to realize that I would leave politics if she asked me to.”

Added Michelle, “Ultimately I capitulated and said, ‘Whatever. We’ll figure it out. We’re not hurting. Go ahead.’” Then she laughed and told him hopefully, “And maybe you’ll lose.”

Obama went back to Shomon and told him he was in. “So I told Dan that I had this conversation with Michelle and she had given me the green light and that what I want to do is roll the dice and put everything we have into this thing.”

Still tapped out from his congressional race, Obama knew he needed start-up cash. So he held a small fund-raiser that netted thirty-three thousand dollars. That allowed him to begin paying Shomon as a full-time campaign manager, as well as hiring an office administrator and a full-time fund-raiser.

BEFORE THAT FUND-RAISER, HOWEVER, OBAMA HAD BEEN MAKING other vital moves. He had a crucial meeting with another important crowd—the key financial supporters of his unsuccessful congressional race in 2000. Obama knew that his fund-raising for a Senate campaign had to far exceed what he had raised in his race against Bobby Rush. So he invited a group of African-American professionals to the house of Marty Nesbitt, who had served as finance chairman of his congressional campaign. Nesbitt is the president of a Chicago parking management company and vice president of the Pritzker Realty Group, part of the Pritzker family empire. A tall, slender African American, he had been friends with Obama for years. Their wives were also close, and Nesbitt’s wife, Anita Blanchard, an obstetrician, delivered both of Obama’s children. The two men played basketball together and mixed with the same Hyde Park neighborhood crowd of young, successful black professionals. Nesbitt was soft-spoken, polite and amiable. He was also extremely active in civic affairs, serving on the boards of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Big Brothers/Big Sisters and the United Negro College Fund, among many others.

Not long after Obama’s loss to Rush, Nesbitt had suggested that Obama might want to run statewide in his next contest. It seemed pointless to try to unseat Rush again after failing so miserably. So when Obama addressed the group of black professionals and mentioned his plans for a statewide race, Nesbitt quite naturally assumed Obama was considering a state office, such as attorney general or treasurer. Then Obama dropped the bomb.

“Barack says he wants to run for the U.S. Senate,” Nesbitt recalled. “Blahhh!! I mean, I literally fell off the couch. And we all started laughing—and he said, ‘No, really, I am gonna run for the U.S. Senate.’” Then Obama proceeded to make a rational argument that he could win such a race. He said that Senator Fitzgerald’s approval ratings were so low that he was destined to lose to a Democrat in 2004. Obama said he believed he could bring together blacks and liberals into a coalition and come out on top in what was looking to be a crowded primary field. “He convinced us in the room that day that he could pull it off,” Nesbitt said. “But he mostly convinced us because we were his friends and we wanted to support him.”

Obama, who had learned the significance of money in politics during his Rush contest, also told them the hard fiscal truth that he was going to need not hundreds of thousands but millions of dollars to pull off a victory. He even broke it down into specifics, telling the group that with three million dollars, he had a 40 percent chance of winning; with five million dollars, he had a 50 percent chance; with seven million, 80 percent. And with ten million, Obama proclaimed, “I guarantee you that I will win.”

Nesbitt said that Obama’s supreme confidence, clear vision and attention to detail convinced them that it was doable. It certainly wasn’t a sure win, but it was doable.

“So we all said, ‘We’ve gotta make a grassroots, ground-level push and get this going,’” Nesbitt said. “But you know, at this point, I was very naive. Barack is not afraid to ask for money. But I didn’t have any idea how far we had to take it, to the next level.”

The next level meant that Nesbitt and Obama had to reach beyond his previous contributor base. In his congressional race, Obama successfully picked up cash from black business leaders and a smattering of lakefront liberals, but he needed to reach even deeper into those pockets and find more. So Nesbitt arranged a weekend getaway to help Obama reach inside the deepest pockets he knew—those of the Pritzker family.

THE PRITZKERS RULE A FAMILY EMPIRE THAT EMBODIES HIGH society and extreme wealth in Chicago. One of the richest families in the country, with a fortune estimated at twenty billion dollars, the Pritzkers began their American story in 1902 when Nicholas Pritzker, a Ukrainian immigrant, opened a law firm in Chicago’s downtown Loop commercial district. Over four generations the family amassed its fortune through Hyatt hotels, financial services and numerous other enterprises. The clan is intensely private, even if they have also been extremely philanthropic. Nesbitt knew that if Obama could sell himself to Penny Pritzker, her support would not only reap huge immediate financial dividends but also be a crucial step in the foundation of a fund-raising network.

So in late summer 2002, Obama, Michelle and their two daughters drove to Penny Pritzker’s weekend cottage along the lakefront in Michigan, about forty-five minutes from Chicago, to sell his candidacy.

Like many people at this point, Pritzker was impressed by Obama’s intellectual heft but was unsure whether he could pull off what he had in mind. It would be up to Obama to sell his vision to a veteran businesswoman who was no easy sale. Pritzker, who has mostly supported Democrats but deems herself a “centrist,” recalled the weekend as a “seminal moment.” She and her husband, Bryan Traubert, were in training for the Chicago Marathon, and under a beautiful sunny sky the couple slipped away for a long run along Michigan’s winding country roads near the lakeshore, all the while discussing whether Obama merited their backing. She described the discussion:

We had known Barack and Michelle previously, but we hadn’t made up our minds about supporting him for the Senate. And we had to make a decision. So we spent some time talking with him about his philosophy of life and his vision for the country. He is a very thoughtful human being in the way he articulates ideas and the way he thinks about the world. And the older I get, the more I realize it is not always what you say, but the way you say it. And that is particularly true in politics. . . . So Bryan and I had a long discussion about Barack and his values and the way he carries and expresses himself, his family and the kind of human beings he and Michelle are—what kind of people they are, as much as about lofty political ideas. Really, at that point the question was, these other people are running and what obligations do you have to the other people? It became clear to us that if Barack could win, he had the intellect, the opportunity, to be an extraordinary leader, not just because he would be an African-American senator, but a male African-American senator. Here is a guy with an amazing intellectual capacity to learn and an interest in learning. . . . But how much did he know about medicine, about business, about foreign affairs and the economy? He was dealing with all these things in fragments and we asked ourselves what was his capacity to deal with these things as a whole? . . . He was someone who views himself as a healer, not a divisive character, but someone who can bring disparate constituencies together. . . . It became clear to us that . . . he is not perfect, but he is bright and thoughtful and confident. He possesses a lot of confidence. That was the seminal moment when we simply decided after that weekend that we would support them.

With Penny Pritzker on board, other influential Chicago-based Democrats and philanthropists soon followed suit: Newton Minow, a Chicago lawyer who advised Senator Adlai Stevenson and Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson; James Crown and members of the wealthy Crown family; John Bryan, then the chief executive of the Sara Lee Corporation.

Obama had not yet announced his candidacy, but he realized he needed more political talent behind him. By now, Adelstein had signed on with another potential candidate, Gery Chico, the former president of the Chicago Board of Education. So Obama turned to the other major political consultant he knew, David Axelrod. A couple of years earlier, Axelrod and his wife, Susan, had thrown a quick fund-raiser for Obama at their downtown Chicago high-rise condominium when Obama’s senate district lines were redrawn to include much of downtown, including their home. Obama was largely anonymous outside Hyde Park at that first gathering, which drew all of twenty people. “We were pulling in people from the pool, urging them, ‘Hey, come meet your new state senator,’” Axelrod said.

After this tepid fund-raiser and Obama’s collapse against Bobby Rush, the political consultant was less than enthused about a potential Senate candidacy for Obama. Axelrod told the hopeful Obama that he thought Obama was a “terrific talent” and “I consider you my friend,” but running for statewide office was “probably unrealistic.” Axelrod was blunt with Obama: “If I were you, I would wait until Daley retires and then look at a mayor’s race because then the demographics would be working in your favor.”

That disappointed Obama, but it did not dissuade him—he still thought the Senate was a good possibility for him. Even so, he soon encountered an even bigger stumbling block than Axelrod’s caution. Carol Moseley Braun, who represented Illinois in the Senate from 1993 to 1999, announced that she might run to reclaim the seat she had lost to Republican Fitzgerald. Moseley Braun had made history as the first African-American woman to serve in the Senate but was defeated by Fitzgerald in 1998 after a tumultuous first term. Allegations arose that her then boyfriend, Kgosie Matthews, who ultimately took over her campaign, sexually harassed female campaign workers, although Moseley Braun said an investigation found no evidence. The couple was accused of spending campaign money on clothes and jewelry, and they were criticized for taking a month-long trip to Africa right after the election. But her major downfall was meeting with the former dictator of Nigeria, General Sani Abacha, without giving advance warning to the Department of State. Abacha had been accused of a host of human rights violations.

Fitzgerald looked extremely vulnerable, having feuded with the GOP power structures in Washington and Illinois. This was the major factor that led Obama to think that unseating him was possible. But if Moseley Braun were in the race, Obama said he would have to defer to her and decline to run. The reality was, he would have no choice: she would gobble up both of his potential bases of support—African Americans and liberals. “There was no way to win,” he said. So Obama asked to meet with her in his senate office in Springfield. “We . . . asked her how serious she was, and her basic attitude was that she had not made up her mind but obviously it is [her] prerogative to potentially run,” Obama recalled. “I understood her position. She had been a trailblazer. It was frustrating for me to think that maybe this was one chance to go after something I really cared about and potentially [I] could not do it. But that is the nature of politics.”

Moseley Braun presented not only a problem for Obama, but a major headache for the Democratic Party powers in both Illinois and Washington. Because she had been a national figure as the first black woman in the Senate, her alleged improprieties in office had been a major embarrassment to the party. And even though Fitzgerald appeared extremely vulnerable, Democrats feared that these past embarrassments would doom her in a general election. Eric Zorn, a liberal columnist for the Chicago Tribune, went so far as to predict that she would be “walloped” by almost any Republican. With a Senate seat seemingly up for grabs, Democrats could ill afford to run a candidate tainted with past scandals.

To keep Moseley Braun out of the race, various Democratic powers close to Obama set out to find her a job elsewhere. “But the problem was, they could not find her employment,” said an Obama confidante. “Nobody could find her any work.” While the job search persisted, Moseley Braun’s indecisiveness about a Senate run began to wear thin on the potential candidates and on Democratic activists looking to support someone in the race. It especially wore thin on Obama, whose political career was hanging in the balance. But that apparently did not matter to Moseley Braun (who declined to be interviewed on the subject). “She felt that [Obama] was a young whippersnapper, a pretender, a cheat,” David Axelrod said. “I think she took it personally. He was essentially messing in her territory. She made it pretty clear that she was not happy about Barack’s entrance.”

As Moseley Braun considered her options, Obama decided to travel to Washington in September 2002, to spend a weekend at the annual Congressional Black Caucus conference in hopes of garnering support for himself. He figured he would meet some influential black lawmakers and ask for their help and guidance. But the excursion was a major disappointment for the earnest Obama. He returned to Chicago significantly disillusioned about the ways of Washington.

A couple of weeks after returning home, he sought the counsel of his pastor and friend, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright. Visibly dejected, Obama slumped onto the sofa in the pastor’s second-floor office at Trinity United Church of Christ. He told Wright that the Senate idea was thoroughly frustrating him because Moseley Braun would not make up her mind whether she was in or out. And not only that, but other names had begun to surface for the race—Illinois comptroller Dan Hynes, whose father was a powerful Chicago ward alderman; Blair Hull, a multimillionaire securities trader; and Gery Chico, formerly a top aide to Chicago mayor Richard Daley and school board president. None was a certain nominee or impinged on his bases, but each had strengths, and each was pulling ahead of him in organizing a campaign operation. Hynes had run statewide before and would have his father’s political machine behind him. Hull would have tens of millions in personal wealth to lavish on a campaign. Chico was already raising significant money and was far along in assembling a campaign structure. Another name floating around was Representative Jan Schakowsky, a liberal from the North Shore suburbs who would have cut directly into Obama’s lakefront support.

“My name should be out there,” Obama told his pastor. “But Carol Moseley Braun won’t say what she’s going to do, and I’m not gonna run against a black woman. If she’s gonna run, then I’m out. Until she says yes or no, I can’t say anything.”

But what truly struck Wright from that meeting was Obama’s astonishment over the black caucus event in Washington. It opened Wright’s eyes once again to just how innocent and idealistic Obama could be about the world of politics. The conference was nothing like what Obama had envisioned, but it was exactly the way Wright, a former adviser to Chicago’s only black mayor, Harold Washington, recalled it.

“He had gone down there to get support and find out who would support him and found out it was just a meat market,” the pastor said in an interview, breaking into a laugh. “He had people say, ‘If you want to count on me, come on to my room. I don’t care if you’re married. I am not asking you to leave your wife—just come on.’ All the women hitting on him. He was, like, in shock. He’s there on a serious agenda, talking about running for the United States Senate. They’re talking about giving [him] some pussy. And I was like, ‘Barack, c’mon, man. Come on! Name me one significant thing that has come out of black congressional caucus weekend. It’s homecoming. It’s just a nonstop party, all the booze you want, all the booty you want. That’s all it is.’ And here he is with this altruistic agenda, trying to get some support. He comes back shattered. I thought to myself, ‘Does he have a rude awakening coming his way.’”

A few months later, Moseley Braun was still dithering as Obama took his annual Christmas season sojourn to his native Hawaii. Deeply dispirited over the prospect of Moseley Braun’s candidacy, Obama rested on Sandy Beach, a fifteen-minute drive along the rugged southeast shoreline from downtown Honolulu. This was the beach of Obama’s youth, the childhood paradise where he spent mindless high school days body-surfing, drinking beer and seeking to convince college women that he was worthy of their attention. With the tree-covered hills of Oahu again cascading behind him, with the tall waves of the Pacific Ocean again crashing before him, the forty-one-year-old Illinois state senator contemplated his future. At this moment, Obama’s ambitious nature was eating at him. He was terrified that all his hard work was coming to naught. The frustrating years trying to organize programs that would assist the impoverished on Chicago’s Far South Side, the decision to forgo a lucrative law career for a meagerly paid civil rights practice, the years foraging in the wilderness of a minority party in the Illinois General Assembly, the days and nights away from his devoted wife and two precious daughters to travel the campaign trail—what had this sacrifice done for him and for the world? That Christmas, Obama’s once bright future seemed as if it was crashing in the surf. Suddenly his grand idea of winning an open seat on the world’s most powerful lawmaking body looked less like a serious notion than a quixotic dream.

For the first time in his professional life, the supremely confident Obama was deeply frightened. He was terrified that the final story of Barack Obama’s political career would be this: Another talented black man with grandiose dreams somehow flamed out and disappeared from public life. Most frightening of all: This story resembled all too much the tale of his father’s unfulfilled dreams.

But then Obama peered out at his two young girls splashing in the ocean with Michelle. They looked playful and happy. Obama reconsidered his dreams and thought, well, perhaps he was not meant to be a senator or a mayor. “I didn’t grow up thinking that I wanted to be a politician,” Obama recalled. “This was something that happened as a sideline, as a consequence of or an outgrowth of my community organizing, and if this doesn’t work out I am fine with it. Kids keep you grounded, and I had to remind myself that it was not all about me and my personal ambitions, that there is a set of broader issues.”

But just as Obama was coming to terms with the notion that his grand political career might never happen, he received a phone call that would again put his personal ambitions front and center. He was still in Hawaii when the news came via cell phone: Moseley Braun had decided against running for the Senate and instead would seek the presidency. Obama knew exactly what he needed to do—and fast. He clicked the cell phone back open and dialed David Axelrod.

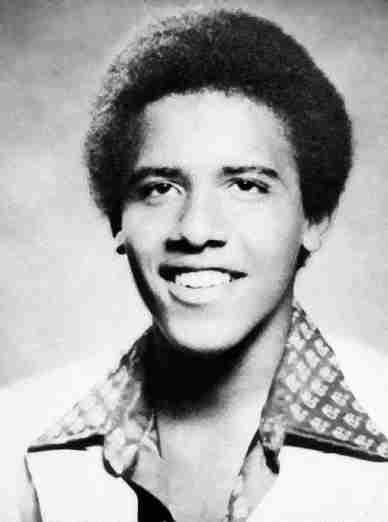

“Barry” Obama in his 1979 senior class portrait at the Punahou Academy in Honolulu. (Courtesy of Punahou Academy)

Obama, fourth from the right in the front row, with his ninth-grade graduation class at Punahou Academy. In Honolulu, the private school was known as the school for the “haole,” or the school for whites. (Courtesy of Punahou Academy)

Obama with the Ka Wai Ola Club at Punahou Academy in 1976. (Courtesy of Punahou Academy)

Obama is making a layup here, but he was largely relegated to warming the bench at Punahou after arguing with his coach about the lack of playing time. The experience taught Obama the pitfalls of challenging authority. (Courtesy of Punahou Academy)

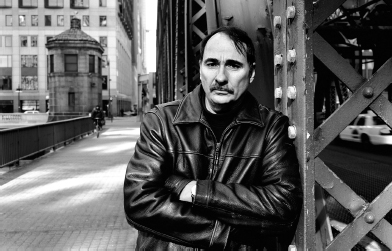

David Axelrod, the premier Democratic political consultant in Chicago, is Obama’s chief media strategist and was the lead architect of Obama’s Senate campaign. A Republican strategist once put Axelrod at the top of a list of “Guys I Never Want to See Lobbing Grenades at Me Again.” (Courtesy of Paul D’Amato)

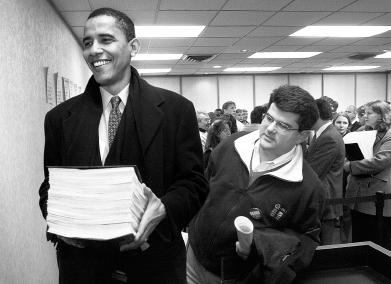

Obama files petitions with the Illinois Board of Elections in Springfield, Illinois, to be placed on the Democratic primary ballot for the U.S. Senate on December 8, 2003. At the right is his first long-term political adviser, Dan Shomon. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Seth Perlman)

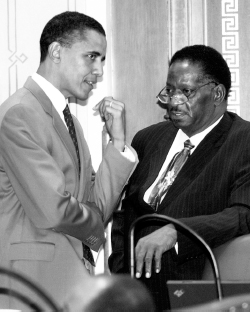

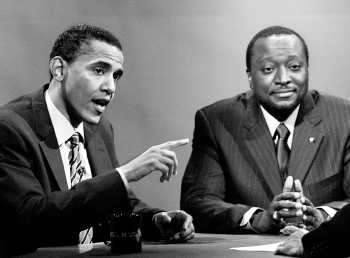

Obama confers with Illinois Senate president Emil Jones Jr. on the floor of the state senate on July 24, 2004. Jones was Obama’s political patron in Springfield, helping Obama mold his legislative record in a fashion that would help Obama win his U.S. Senate race that year. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Randy Squires)

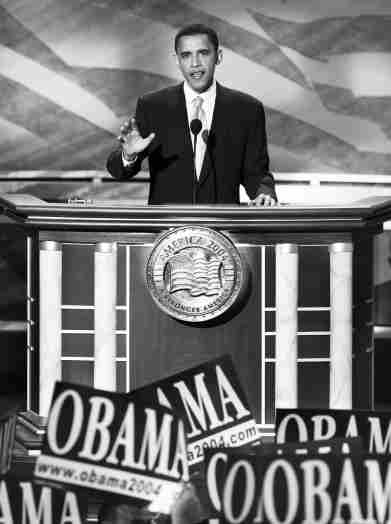

Obama delivers his now-famous keynote address to the Democratic National Convention in Boston on July 27, 2004. The speech propelled him onto the national stage. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Ron Edmonds)

Jack Ryan was Obama’s first Republican opponent in the 2004 U.S. Senate race until the former investment banker was felled by allegations from his ex-wife, a Hollywood actress, that he pressured her to have sex in public. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Nam Y. Huh)

Alan Keyes was Obama’s second Republican foe in the 2004 Senate race. The bombastic Keyes got under Obama’s skin when he continually challenged Obama’s Christianity, even charging that “Jesus would not vote for Barack Obama.” (Courtesy of Associated Press/Nam Y. Huh)

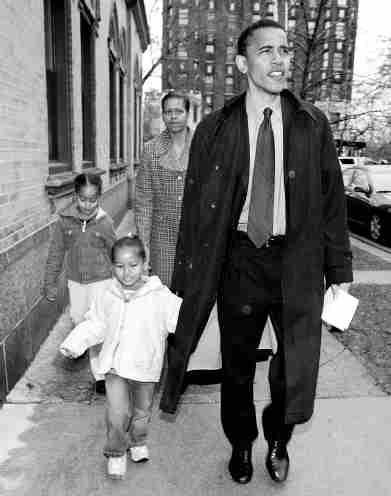

Obama leaves a Chicago polling station with Michelle and his daughters, Sasha, front left, and Malia, after voting in November 2004. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Nam Y. Huh)

Obama and his oldest daughter, Malia, then 6, along with his wife, Michelle, and their second daughter, Sasha, then 3, celebrate Obama’s Senate victory in November 2004. Obama became the third African American since Reconstruction to hold a U.S. Senate seat. (Courtesy of Associated Press/M. Spencer Green)

Obama talks with his staff in his office in the Hart Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill in February 2006. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

Craig Robinson, Obama’s brother-in-law, initially worried that his sister Michelle would “jettison” Obama if he failed to meet her expectations. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Stew Milne)

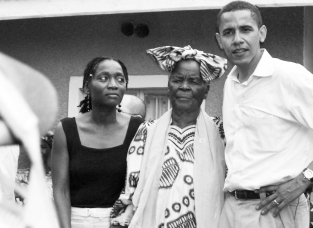

As media chaos engulfs them, Obama greets his paternal grandmother, Sarah Hussein Obama, at his father’s farming compound in the village of Kolego in western Kenya in August 2006. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Sayyid Azim)

Obama and his traveling entourage are swarmed by Kenyans as he visits the Nairobi slum of Kibera in August 2006. “I love all of you, my brothers, all of you, my sisters!” Obama told the crowd. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Gary Knight VII)

Obama comforts Antoinette Sitole as they view the historic photo of her and her slain brother in the Hector Pieterson Museum in Soweto, South Africa, in August 2006. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Themba Hadebe)

In Nairobi, Kenya, Gregory Ochieng held aloft a portrait of Barack Obama that he had painted and then delivered to the visiting U.S. senator in August 2006. “He is my tribesman,” Ochieng said of Obama. (Courtesy of David Mendell)

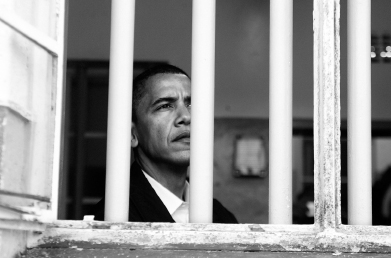

Obama’s traveling media entourage snuggles up close in August 2006 as the U.S. senator tours the Robben Island prison in South Africa, where Nelson Mandela and other anti-apartheid activists were imprisoned. (Courtesy of David Mendell)

Obama strikes a pose as he peers through the bars of the jail cell where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island just off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Obed Zilwa)

Joined by his half sister, Auma Obama, and his paternal grandmother, Sarah Hussein Obama, Barack Obama answers media questions on his father’s farming compound in western Kenya in August 2006. Auma said she worries that her brother is driven by the same perfectionism and ambition that overtook their father’s life. (Courtesy of David Mendell)

Obama chats with top aide Robert Gibbs, one of the key architects of his ascension, while they await Obama’s appearance on CBS’s Face the Nation in January 2007. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Aynsley Floyd)

Anthony Direnzo of Norfolk, Massachusetts, and Lauren McGill of Blacksburg, Virginia, appear to be enraptured as Obama speaks at a rally at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, in February 2007. Obama’s support is especially strong on college campuses. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Susan Walsh)

Ten-year-old Donavan Dodds seems thrilled to shake hands with Obama after a campaign rally at Georgia Tech University in Atlanta in April 2007. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Gregory Smith)

Now a full-fledged presidential candidate, Obama speaks at a campaign stop in Sioux City, Iowa, on April 1, 2007. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Nati Harnik)

Maya Soetoro-Ng, Obama’s half sister, said her ambitious, wandering brother was compelled to leave Hawaii, in part because of the isolated atmosphere of the Pacific islands. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Lucy Pemoni)

Michelle Obama, whom her husband describes as “my coconspirator,” has become a partner on the campaign trail as he seeks the presidency. She speaks here in Windham, New Hampshire, in May 2007. (Courtesy of Associated Press/Jim Cole)