The Obama Administration is clearly committed to a policy of using remotely piloted drones to commit targeted killings. In fact, it has significantly increased the number of drone attacks in comparison to the Bush Administration.1 Scholars have addressed both targeted killing2 and the drone policy;3 the latter has been the subject of Congressional hearings,4 public debates, academic conferences, a major public address by the State Department Legal Advisor,5 and innumerable newspaper articles.6 Needless to say, the drone attack policy is not controversy-free. Those engaged in the public debate must focus on proposing both a legal framework and appropriate operational guidelines to enhance effectiveness and efficacy.

Targeted killing and drone attacks are philosophically similar and premised on comparable legal analysis, even though operational differences clearly exist. Both Israel and the United States have concluded that preemptive self-defense justifies killing a target that the intelligence community has determined is involved in planning or executing a future terrorist attack. From the perspective of international law, an expansive reading of the inherent right of self-defense in Article 51 of the U.N. Charter is at the policy’s core.7

Given the inherent moral, legal and operational complexity of this subject, it is important to articulate and define terms that will hopefully facilitate a reasoned, nuanced and sophisticated conversation. Unfortunately, much of the public debate regarding drones and targeted killing has been distinguished by a lack of understanding regarding the policy—articulation and implementation alike—and the attendant cost–benefit analysis essential to a rational discussion. The discussion here will elaborate on the constituent aspects of a targeted killing, including terms such as legitimate target, threat and imminence, in order to demonstrate the need for a criteria-based process that analyzes such concepts sufficiently.

Targeted killing can be implemented with unmanned aerial vehicles, operated by remote control thousands of miles removed from the “kill site,” like the U.S. drone program. Israel’s targeted killing policy, in contrast, is largely implemented by manned helicopters. In addition, it is important to note that targeted killing can also be the responsibility of ground forces.8 For example, the specific scenario presented later in this chapter refers to a targeted killing dilemma involving Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) ground forces in which I was directly involved.9

The question that drives this chapter is the following: what are the criteria necessary for a targeted killing decision? The working premise is that targeted killing—as a policy—is both lawful and effective. In that sense, this chapter brackets off many of the normative legal and philosophical questions that determine, in the abstract, the lawfulness or moral permissibility of targeted killing. These questions include, inter alia, the proper scope of Article 51 self-defense, the question of imminence and preemptive self-defense, the role of non-state actors, and the status of terrorists as either civilians or combatants subject to the reciprocal risk of killing. Instead, this chapter cuts across the legal terrain in a wholly different manner: assuming that targeted killing is legally and morally justified in the abstract, how can individual targeted killing decisions be made such that they comply with the basic principles of both law and morality? Do law and morality place additional restrictions on the practice that restrict how a particular country can—and should—implement a targeted killing policy? Ironically, this reverse methodology will then provide some insight into the general legal and moral principles underlying targeted killing.

In other words, assuming the overall legality of targeted killing in the abstract does not mean that every targeted killing is both lawful and effective. Indeed, how the policy is implemented in a particular situation is relevant for determining its legality; that is, the theoretical architecture of the targeted killing policy in both the United States and Israel is just the first step in analyzing the legality of a particular strike. While the theory at the core of the policy emphasizes self-defense, an equally important question is how the policy is implemented in fact. That is the distinctive question addressed in this chapter.

Furthermore, the legal framework is only one facet of an effective paradigm. In the absence of a process—one based on criteria and operational realities—effective decision-making is fundamentally limited. In the arena of targeted killing, the decision is, in many ways, the most important aspect of the operation; the process by which the decision is made is truly central to the lawfulness of the action. Therefore, this chapter argues that a criteria-based approach to the decision-making process simultaneously facilitates operational success and minimizes harm to innocent civilians. The first section presents two components of the theoretical underpinnings for the more practical, operational discussion to follow. First, the need for criterial decision-making by a legal advisor, rather than intuitionism at the discretion of a military commander, is fundamental in counterterrorism in general and targeted killing in particular. Second, the legal and moral principles at the heart of targeted killing drive the criteria-based process and govern the relevant issues and determinations. The second section of the chapter presents a scenario that highlights the need for a criteria-based process and the dangers of an intuition-based approach, and then introduces the key issues and components of such a process. Finally, the third section builds the criteria-based process, focusing on the central elements of threat, source and target and how to identify and apply the relevant criteria to ensure lawful and effective counterterrorism.

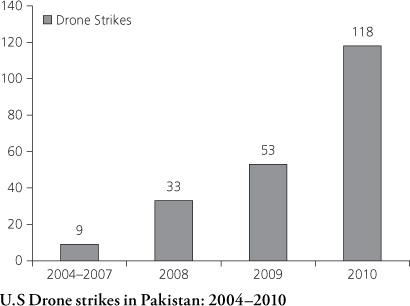

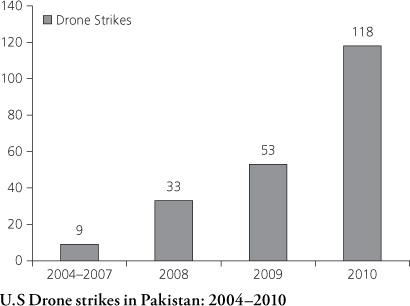

The proposal that targeted killing be subject to legal criteria is not a given. Some might suggest that imposing criteria on the decision-maker arguably impedes aggressive operational counterterrorism. A powerful argument can be made that its implementation significantly hampers command discretion. In this view, the military commander should make an all-things-considered judgment about how to proceed—a judgment that relies more on his military and command experience than it does on specific criteria determined in advance by experts in the laws of war and then applied in practice by military lawyers. The rationale for this unfettered discretion- and intuition-based approach would be that “excessive” involvement by lawyers hampers the ability of commanders to make quick and aggressive decisions to hit targets of opportunity. This is a legitimate concern that cannot be easily dismissed and warrants serious discussion. It is, frankly, a discussion that must be had for a number of reasons, most notably because President Obama has significantly increased the implementation of the drone policy in comparison to President Bush. The chart below depicts the dramatic increase in the use of drones under President Obama; all signs clearly indicate this policy will continue to be implemented for years to come.

Source: O’Connell, Mary Ellen, “Unlawful Killing with Combat Drones: A Case Study of Pakistan, 2004–2009. Shooting to Kill: The Law Governing Lethal Force in Context,” Simon Bonitt (ed.), Notre Dame Legal Studies Paper No. 09–43 forthcoming. Available at: <http://ssrn.com/atract/501144>.

The core requirement to minimize collateral damage is one of the fundamental motivations for criteria-based decision-making in targeted killing. In the absence of criteria for decision-making, at best targeted killing will pay mere lip service to this key international law requirement. In that vein, the recent CIA claim that not one noncombatant has been killed in drone attacks in 2011 is,10 at the least, an eyebrow raiser.11

The world of operational counterterrorism decision-making is extraordinarily complex; it is also high-risk and fraught with danger. The burdens imposed on the decision-maker are extraordinary because of the overwhelming responsibility to ensure the safety of soldiers under his command and also to protect innocent civilians. Although the rules of engagement that codify when an “open fire” order may be given are carefully written and subject to thorough examination by a wide range of experienced professionals, the ultimate decision is made in the field by a commander exercising discretion subject to an infinite set of circumstances.

Precisely because those circumstances impact the commander’s judgment, the criteria-based model is an essential mechanism for increasing the effectiveness of the targeted killing policy. To that end, I define effectiveness as the correct identification and targeting of a legitimate target (based on imminent threat and necessity) subject to stringent collateral damage restrictions. Implementing this policy in accordance with this two-part test demands a criteria-based approach.

This chapter is based on my twin perspectives of having served as a legal advisor in the IDF and now as a professor of law with numerous opportunities to reflect on decisions in which I was involved.12 My concentration on “process” stems from my belief that a criteria-based model of decision-making is essential to minimizing collateral damage and enhancing the effectiveness of existing policies. Simply put, beyond the legal, moral and theoretical underpinnings, lawful targeted killing must be based on criteria-based decision-making, which increases the probability of correctly identifying and attacking the legitimate target. A state’s decision to kill a human being during a counterterrorism operation must be predicated on an objective determination that the “target” is, indeed, a legitimate target. Otherwise, the state’s action is illegal, immoral and ultimately ineffective. Subjective decisions based on fear or perception alone pose grave danger to both the suspected terrorist and innocent civilians.

It goes without saying that many object to the killing of a human being when less lethal alternatives are available to neutralize the “target.” Others will suggest—not incorrectly—that targeted killing is nothing but a manifestation of the state acting as “judge, jury and executioner.” On the other hand, the state has a responsibility to develop and implement measures protecting innocent civilians from enemies who kill and maim innocent civilians. The need for an objective determination that the person in the crosshairs is a legitimate target requires a method to enhance the decision-making process in the face of extreme pressure.

Effective counterterrorism requires the nation-state to apply self-imposed restraints; otherwise violations of both international law and morality in armed conflict are all but inevitable. Aharon Barak, the former President (Chief Justice) of the Israeli Supreme Court addressed the issue of self-imposed restraint in his seminal article, “A Judge on Judging.”13 According to Barak, the nation-state is subject to legal and moral restrictions with the understanding that limits on state power are the essence of the rule of law. In order to implement Barak’s theory on a practical basis, the nation-state must develop clear criteria with respect to operational decision-making.14 This is in direct contrast to intuitive decision-making, which, dependent on the notion that a person simply knows what is right, is devoid of articulated standards and guidelines.

As background, the theater of war, regardless of whether it is traditional warfare between nation-states or state/non-state conflicts, requires articulated standard operating procedures addressing a wide range of issues including (but not restricted to): open-fire orders, treatment of captives, prohibitions on particular weapons, limits on use of force with respect to collateral damage and application of the rules of proportionality. Indeed, the law of armed conflict—that is, the law governing the conduct of hostilities—mandates such clear-cut parameters. A standard-less theater of war in which these ground rules are neither agreed upon by international convention nor self-imposed will result in unconscionable harm to innocent civilians, ill-treatment of captives and unlimited use of force.

For commanders, who are responsible for both the conduct and the welfare of their soldiers, a theater of war not subject to restrictions and criteria would both subject their soldiers to extraordinary harm (through unlawful means and methods of attack or upon capture) and give them the freedom to act immorally, devoid of standards of decency and humanism. A standard-free military paradigm where soldiers’ conduct is not subject to limits or restrictions would be a disturbing reversion to a Hobbesian State of Nature.

As a general methodology for moral theory, intuitionism has many adherents.15 But intuitive decision-making, rather than criteria-based decision-making, is particularly problematic if it is imported into the realm of operational counterterrorism. As Professor Sauter writes:

This intuitive thought process is vastly different from the analytical approach. Analytic thought involves defining the problem, deciding on exact solution methodologies, conducting an orderly search for information, increasingly refining the analysis, aiming for predictability and a minimum of uncertainty. Intuitive thought, on the other hand, avoids commitment to a particular strategy. The problem-solver acts without specifying premises or procedures, experiments with unknowns to get a feel for what is required.... [Intuitive decision-making] has its faults, most obvious of which is the absence of data based theories and the use of methodology that cannot be duplicated.16

The instinctual response is arguably appropriate when an individual is confronted with a stark life-and-death dilemma where a failure to respond quickly and aggressively will, in near certainty, result in death. For example, if a homeowner were to walk into his home and catch an intruder by surprise, the principle of self-defense would justify—depending on the circumstances—a violent reaction.

Moreover, an intuition-based approach leaves little in the way of parameters for post-operation analysis. If there is no process for the decision, it will be difficult to judge when the decision was right or wrong. Such a lack of parameters seems to fly in the face of the basic goals of a legal regime, especially one regulating life-and-death issues. The essence of targeted killing is proactive—not reactive—self-defense based on sophisticated intelligence gathering and analysis, and careful consideration of the international law principles of collateral damage, proportionality and military necessity.17 The criteria-based approach facilitates careful identification of a legitimate target and ex post evaluation of this decision, thus enhancing both short- and long-term effectiveness.

In the context of counterterrorism, however, intuitionism is profoundly dangerous due to its lack of process and criteria. Without these, operational decision-making loses its legal and ethical moorings. The decision-maker will be acting primarily on what he believes he sees without taking into consideration all relevant information. A decision based exclusively on the action-reaction of one individual, divorced from broader considerations, poses extraordinary dangers.

Targeted killing operations involve more than a simple analysis of “threat or no threat,” where a combination of process and instinct may be an appropriate fit. In reality, in counterterrorism—and targeted killing in particular—individuals are making decisions almost entirely based on information received second- or even third-hand, and in an environment that blends extraordinary intensity with multiple competing and complex factors. Simply having a process alone—such as the requirement that a military lawyer approve the operation—is not sufficient. Criteria, guidelines and standards that define the parameters—and even the paradigm—for the decision are key tools for ensuring lawfulness and effectiveness in a targeted killing policy.

A decision to authorize a targeted killing requires a confluence between the imminence of the threat and the necessity of responding with deadly force. As Section III below explains in greater detail, such determinations depend on a careful and sophisticated analysis of the intelligence, the parameters of the operation, the situation on the ground, including the presence of innocent civilians, and above all, the nature of the threat posed. Several factors play a central role here: the degree of danger; the strength of the intelligence; the reliability and credibility of the source; and timeliness, both of the intelligence and the attack.

Appropriate consideration of these factors is the only mechanism for implementing a targeted killing in accordance with the international law requirements set forth below. In essence, a successful targeted killing is not simply one that hits the designated target. Rather, a successful targeted killing is one that hits the target while ensuring protection of innocent civilians and upholding the rule of law. Creating a structured system and process based on criteria and standards will facilitate state action within these parameters; the absence of criteria will, unfortunately, enable a restraint-less paradigm and lead to unwarranted and unjustified collateral damage.

For example, more than one type of potential terrorist attack can pose a threat, but not all trigger the justifiable use of targeted killing. There are relevant differences between a plot to plant a bomb in a coffee house somewhere in Jerusalem next week, a plan to throw Molotov cocktails at a protest, and a suicide bombing operation at a designated pizza parlor. Degree of harm, concreteness of plan and information, number of similar attacks or attackers, operational feasibility of detention instead of targeted killing—these are just a few factors which can change continually as the operational landscape and intelligence information shift and fill out. Which factors should be included? How should they be weighed? Whose information can be trusted? Whose information carries more or less weight? Only a criteria-based process can manage a decision-making paradigm of this complexity and intensity with full regard for the operational and legal obligations.

Furthermore, criteria-based decision-making contributes greatly to reliability and consistency: similar situations beget similar responses and results. This notion of “repeatability” is essential for operators, civilians, judges and policy makers, and depends on rational criteria. Not only might the same decision-maker respond differently to what should be similar situations (or similarly to what should be different situations), but targeted killing inherently involves multiple, and often different, decision-makers. Intuition and unrestrained discretion pose far too significant a risk of subjective responses and cannot ground lawful and moral decision-making in such a scenario.

Emphasizing a criteria-based approach rather than an intuition-based approach minimizes risk and thus enhances protection of the otherwise unprotected civilian population and the state’s own citizens. By imposing limits and criteria on both the decision-maker and the actor, the decision-making process creates a structure for determining when an open fire order can be given. The process rejects spontaneity and minimal infrastructure. In that sense, intuitive decision-making, as defined by Professor Sauter, arguably contributes to a “Lord of the Flies” approach to operational counterterrorism. As President Barak convincingly argues, nothing could be more dangerous to a democracy engaged in aggressive operational counterterrorism.

I argue that the principal tenet of a sound targeted killing policy is that the need to prevent a specific, planned attack justifies killing the individuals involved in the attack. The framework relies on a combination of robust self-defense under international law and key principles of the law of armed conflict. The legal framework is complex and well developed, thus firmly supporting the push for a criteria-based approach over intuitionism. As the following discussion shows, these principles would face disregard or emasculation in the absence of a coherent and rational process for decision-making.

The principle of self-defense is a fundamental principle of customary and conventional international law and its modern foundations date back to the Caroline Incident. The Caroline was a U.S. steamboat attempting to transport supplies to Canadian insurgents. A British force interrupted the Caroline’s voyage, fired on it, set it on fire and let it wash over Niagara Falls. Webster said that Britain’s act did not qualify as self-defense because self-defense is only justified “if the necessity of that self-defense is instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.”18 According to Webster, Britain could have addressed the Caroline’s threat in a more diplomatic manner. He thus limited the right to self-defense to situations where there is a real threat, the response is essential and proportionate and all peaceful means of resolving the dispute have been exhausted. Article 51 of the U.N. Charter reaffirms this inherent right of self-defense. Although the Charter provision specifically speaks of self-defense in the event of an “armed attack,” states have traditionally recognized a right to anticipatory self-defense in response to an imminent attack, as set forth in the Caroline framework.

Targeted killing is the manifestation of self-defense at its most basic: the nation-state is defending its citizens from violent attack. It does, however, demand careful analysis of the nature of self-defense under international law. International law was originally intended to apply to war and peace between recognized states; the concept of non-state actors was not contemplated. In addition, a thorough review of international law demonstrates that terrorism as a subject of international law has only been considered in the past few decades. Clearly, the tragic events of 9/11 significantly contributed to this development. Thus, in studying responses to terrorism under international law, one of the issues that must be examined is the relevance and applicability of international law to this new form of warfare.

The question that must be addressed in the face of these developments is: does the right to self-defense allow states to effectively combat both state-sponsored and non-state-sponsored terrorism? Because the fight against terrorism takes place against an unseen enemy, the state, in order to defend itself adequately, must be able to take the fight to the terrorist before the terrorist takes the fight to it. In other words, the state must be able to act preemptively in order to deter terrorists or prevent them from completing their terrorist plot. By now, we have learned the price society pays if it is unable to prevent terrorist acts. The question that must be answered—both from a legal and policy perspective—is what tools should be given to the state to combat terrorism? Rather than wait for the actual armed attack to occur, the state must be able to act anticipatorily (as in the Caroline incident) against the non-state actor (a factor not considered in Caroline).

Beyond the legal justification for the use of force (self-defense against a non-state actor), the conduct of the operation must be consistent with existing principles and obligations under the law of armed conflict. First, the fundamental principle of distinction requires that any attack distinguish between combatants and innocent civilians. An individual can be a legitimate target of attack based on his status as a member of the enemy forces, whether a soldier in the regular armed forces of an opposing state in the conflict or a fighter in a non-state armed group engaged in the conflict. Alternatively, the determination that an individual is a legitimate target can be based on his or her conduct. Thus, civilians who “directly participate in hostilities” lose their immunity from attack and become legitimate targets during the time they are participating in hostilities.

Second, international law requires that targeted killing operations meet a four-part test: (1) it must be proportionate to the threat posed by the individual; (2) collateral damage must be minimal; (3) alternatives have been weighed, considered and deemed operationally unfeasible; and (4) military necessity justifies the action. Even though the individual targeted is a legitimate target, if the attack fails to satisfy these obligations, it will not be lawful. Thus, the Special Investigatory Commission examining the targeted killing of Saleh Shehadah recently concluded that although the targeting of Shehadeh—head of Hamas’ Operational Branch and the driving force behind many terrorist attacks—was legitimate, the extensive collateral damage caused by the attack was disproportionate.19 As will be shown in greater detail below, the absence of a criteria-based decision-making process can severely compromise adherence to, and implementation of, these key obligations.

The uncertainty inherent in contemporary conflict has significantly complicated wartime conduct. However, that ambiguity cannot—must not—be used to facilitate departures from these key principles or to justify the commission of war crimes. The self-imposed restraint doctrine articulated by Justice Barak is the philosophical and jurisprudential essence of lawful operational counterterrorism.20 It imposes on commanders the obligation—in accordance with Barak’s legal architecture—to develop strategies that facilitate aggressive counterterrorism while imposing restraint on soldiers facing a foe dressed exactly the same as the innocent civilian standing next to him. Specifically, Barak noted:

The examination of the “targeted killing”—and in our terms, the preventative strike causing the deaths of terrorists, and at times also of innocent civilians—has shown that the question of the legality of the preventative strike according to customary international law is complex. The result of that examination is not that such strikes are always permissible or that they are always forbidden. The approach of customary international law applying to armed conflicts of an international nature is that civilians are protected from attacks by the army. However, that protection does not exist regarding those civilians “for such time as they take a direct part in hostilities.” Harming such civilians, even if the result is death, is permitted, on the condition that there is no other less harmful means, and on the condition that innocent civilians nearby are not harmed. Harm to the latter must be proportionate. That proportionality is determined according to a values based test, intended to balance between the military advantage and the civilian damage. As we have seen, we cannot determine that a preventative strike is always legal, just as we cannot determine that it is always illegal. All depends upon the question whether the standards of customary international law regarding international armed conflict allow that preventative strike or not.21

International law requires distinguishing between the terrorists and innocent civilians, but even beyond that, Barak’s thesis imposes a heavy burden on commanders. According to Barak, the state must impose limits on itself; otherwise, illegality and immorality are all but certain in counterterrorism operations. How that plays out is essential for our discussion because it accentuates the requirement of command discretion. The following vignette offers a useful example:

An IDF battalion commander (Lt. Col.) was given an order to detain three suspected terrorists believed to be in the West Bank city of Nablus (Shekem). At the city outskirts, he received an intelligence report at 10:00 am that hundreds of school children were milling about the village square. According to the commander, three options were operationally viable: (1) continue and ignore any consequences; (2) retreat; or (3) play a game of cat and mouse. It became clear to the commander that the reason why the school children were milling about (and not in school) was that the school principal had been ordered to close the school when the IDF force was spotted. This was a classic human shielding by the terrorists, a clear violation of international law; nevertheless, the risks to the innocent civilian population (the school children)—willingly and deliberately endangered by terrorists—led the commander to abort the mission.22

The vignette shows that the two concepts—self-defense and the four fundamental principles listed above—are not in conflict. Instead, they must be considered in formulating international law’s response to modem warfare, which is clearly a very different kind of war than all previous ones. Self-defense (in the form of targeted killing), if properly executed, not only enables the state to protect itself more effectively within a legal context but also leads to minimizing the danger to innocent civilians caught between the terrorists (who regularly violate international law by directly targeting civilians and by using innocents as human shields) and the state. As David explains, “in time of war or armed conflict innocents always become casualties. It is precisely because targeted killing, when carried out correctly, minimizes such casualties that it is a preferable option to bombing or large-scale military sweeps that do far more harm to genuine noncombatants.”23

Preemptive self-defense aimed at the terrorist contains an element of pinpointing: the state will only attack those terrorists who are directly threatening society. The fundamental advantage of preemptive self-defense subject to recognized restraints of fundamental international law principles is that the state will be authorized to act against terrorists who present a real threat prior to a plot’s consummation (based on sound, reliable and corroborated intelligence information or sufficient criminal evidence), rather than reacting to an attack that has already occurred in the past.

The only difference between the Caroline doctrine and the version of preemptive self-defense espoused here is the extension of Caroline to non-state actors involved in terrorism. If properly executed, this policy would reflect the appropriate response by international law in adjusting itself to the new dangers facing society today. In essence, it recognizes the state’s right to act preemptively against terrorists planning an attack. Although there is much disagreement among legal scholars as to the exact threshold that constitutes “planning,” targeted killing as preemptive self-defense enables the state to undertake all operational measures required to protect itself. As states increasingly engage in conflicts against non-state actors, international lawyers will have to address the precise contours of this right. However, the goal of this chapter is not to provide a complete account of preemptive self-defense, but rather to explain how a theory of preemptive self-defense should be operationalized into a particular policy for conducting targeted killings.

The scenario below reflects operational and legal dilemmas at the core of the targeted killing decision-making process: that is, whether the information provided by the intelligence community to the commander is sufficient to engage an individual. In accordance with standard operating procedure, the commander communicates with the legal advisor; the latter’s assessment is based on the law and morality of armed conflict and policy effectiveness.

Consider the following situation. An individual receives a phone call at 3:00 am: “We need to talk; the window of opportunity to neutralize the target is only a few minutes.” The commander is calling his legal advisor with the following question: based on the following facts, is the proposed targeted killing legal?

The intelligence community supplied the commander with information received from a case officer,24 who met with a source, who heard from someone that so and so said such and such, which then led the case officer to issue a request for a targeted killing. Based on this flimsy piece of information, the commander had stationed 10 soldiers at the target’s supposed location.

The conversation is tense, compounded by the steady flow of reports the commander receives in his earpiece about the target’s movements and the inherent tension of the operation—does he give the “shoot to kill” order? The legal advisor understands the commander’s imperatives: the mission and the safety of his troops. Both focus on two key issues: (1) engaging an individual identified as a threat to state security is precisely what they signed up for; and (2) they have a responsibility to ensure that an order to “engage” is given only when it is fully justified by the circumstances and in accordance with standing orders regarding rules of engagement.

The commander hears increasingly agitated information from the spotter; the situation grows more dangerous with each passing minute because the target is closer, the unit spends more time in the field, and it is close to sunrise. The legal advisor hears this and faces the tension of assessing the information from the commander and making a decision in light of the legal and moral principles guiding state action.

From an operational perspective, the commander was ready to give the “open fire” order. In response to the legal advisor’s questions, he was convinced that he had taken all necessary measures to minimize collateral damage. He had also made clear that his soldiers were ready for an “open fire” order; the ambush was properly organized, the soldiers were ready and the target was in the crosshairs. By daybreak, the target, reported to be wearing a blue shirt and blue jeans and holding a bag in his left hand, would either be dead or safely on his way.

This type of situation—making a decision at 3:00 am, in a time-sensitive environment, fraught with anxiety and high risk, based on imperfect intelligence information provided by someone who neither the commander nor the legal advisor would ever meet or know—highlights the extraordinary nature of decision-making in this situation. What should be the guiding force: intuition and a gut reaction based on unfettered discretion? Or a process based on rigorous criteria?

The discussion in Section I above demonstrates the shortcomings of intuitionism and unfettered discretion in this situation, shortcomings that can have drastic and fatal consequences. Instead, the decision-making process depends on information and analysis, on an objective process that can identify, isolate and target the key pieces of information. The following questions are essential to that process and are now summarized as follows:

Who is the target?

How do you know that he is the correct target? For example, do his clothes and his appearance match what the source told the case officer?

Who is the source? Commanders rarely—if ever—have direct contact with sources and are totally dependent on analysis and reports from case officers.

What are the alternatives—without unduly endangering the lives of the soldiers—to neutralizing the target? Can the target be detained instead?

What are the risks of collateral damage and have you endeavored to minimize collateral damage?

What is the quality and training of your soldiers?

Has your unit suffered from disciplinary issues? An ill-disciplined unit is, in all probability, not combat ready because the commander has expended too much time and energy on discipline rather than training.

What weapons do your soldiers have at their disposal and when was the last time they participated in a night-time mission? How good is the soldiers’ night-time vision?

Are you (the commander) with your soldiers? If yes, will you be the “trigger man”? If not, who is the officer in command and where are you?

What is your previous experience with the case officer and when was the last time the case officer spoke with the source? Did he assure you that the source met the four-part test regarding the source’s reliability?

Are you and the case officer convinced that the source, with whom the commander has not spoken, does not have an ulterior motive or a grudge against the target?25

This checklist approach forms the nascent beginnings of a criteria-based methodology for operational decision-making. The circumstances are less than ideal: imperfect intelligence information, time-limited decision-making framework, high risk with respect to possible loss of life (soldiers, identified target and innocent civilians alike) and foreseeable danger to national security. Without a process based on criteria and objective considerations, codified in a military-ready checklist, those factors will play a much more substantial—and problematic—role in any decision-making process.

In the face of the extraordinary time pressure, any legal advisor would have great difficulty being systematic with questions and might fumble from issue to issue in a haphazard way. Without a checklist, there is no clear road map to guide decision-makers through the information that they need to collect. Even if they asked many of the right questions, the absence of a checklist might produce mistakes under time pressure. For example, in the scenario above, the legal advisor would likely have given greater weight to the case officer’s report and insufficient weight to what the commander was actually seeing at the time.26 These considerations form the central impetus for the proposal for a criteria-based decision-making process.

Criteria-based decision-making is intended to foster objective decisions. The proposed model is based on the nation-state’s obligation to respect international legal principles and norms. That commitment—based on customary international law, international conventions and treaties—imposes restrictions and burdens that inherently limit counterterrorism operations. It is also what distinguishes the nation-state from a non-state actor that is held accountable neither to international law nor international public opinion.

The criteria-based decision-making process seeks to enhance understanding of the process and to provide tools to the decision-maker in a situation where uncertainties far outweigh certainties, where the unknown largely outnumbers the known.27 Thus, the goal is not to hinder decisions and implementation, but to minimize mistakes. In these circumstances, a mistake is primarily the targeting of an otherwise innocent individual because of faulty intelligence information, incorrect assessment of received intelligence, or incorrect calibration of coordinates when opening fire. Although the incidental death of an innocent bystander during a targeted killing is doubtlessly unfortunate, international law accepts collateral damage provided it is not excessive, although this term is rarely quantified with any great precision.

The proposal is not—under any circumstance—intended to facilitate or justify criminal conduct of soldiers; a soldier or commander who violates standing orders and unlawfully causes the loss of innocent life must be either brought before a disciplinary hearing or court-martialed; the same is true for a soldier who follows a blatantly unlawful order.28 Rather, the proposal’s goal is to facilitate implementation of effective counterterrorism measures within the framework of respect for individual rights and the protection of civilians.

The first step in creating an effective counterterrorism measure is analyzing the threat, including its nature, its origin, and when it is likely to materialize. This latter factor—imminence—will have a significant legal impact on the operational choices made in response. Taken together, these considerations directly impact the international law obligation of distinction and the notion of direct participation in hostilities. A person who is a legitimate target because of his status as a combatant is considered to be a threat at all times by virtue of that very status. In contrast, a civilian who is a legitimate target based on his conduct is—under the same framework—a threat when he is “directly participating in hostilities” as that concept is understood within international humanitarian law.

In a nutshell, the jurisprudential underpinning of targeted killing is that it is necessary to protect the civilian population in the face of an imminent threat. Simply put, self-defense is at the core of the policy. This includes a determination that a particular individual poses an imminent threat and that no viable alternative exists to mitigate the threat posed by that individual. The two critical questions, then, in both the theoretical and practical discussion, are whether a viable threat exists and whether that threat is imminent. The imminence requirement is one of the most analyzed yet controversial aspects in the use of force literature. To suggest that targeted killing is only lawful when used against an individual minutes away from detonating himself inside a packed coffee shop is to misunderstand the range of imminence. But drawing a more exact line is difficult and requires further analysis.

Specifically, the imminence requirement as traditionally understood can sometimes lead to problematic results.29 For example, suppose that the intelligence community determines that an individual is involved in planning a future terrorist attack and that his role is essential to the plan’s success. Furthermore, suppose that intelligence indicates that the terrorist attack is being planned for next week, but the intelligence community has determined that the window of opportunity to target the terrorist is limited to now. If the target’s location has been identified and arrest is not feasible, then the targeted killing ought to be justified, notwithstanding the fact that the terrorist attack is still a week away from being consummated. In other words, any analysis regarding the lawfulness of targeted killing ought to include the question of whether he or she can be targeted effectively. Some scholars have solved this problem by arguing for a switch from imminence to a new requirement of immediate necessity, a position adopted by the U.S. Model Penal Code in the context of individual self-defense under domestic criminal law, and also supported by some international lawyers. This theoretical move could be justified on the grounds that imminence appears to be a proxy for necessity anyway; what relevance does imminence have other than its implication that the use of defensive force is necessary at that moment in time when it is actually exercised?

Other scholars have solved the same problem with a far less ambitious proposal: develop a nuanced theory of imminence that recognizes that imminent threats can extend further back in time than previously acknowledged. For self-defense to be effective, imminence should not be limited to the suicide bomber minutes away from detonation; it should also extend to the individual who is planning the attack. Although the planning of the attack may happen days before the bomb is actually detonated, the planning may still be imminent enough to justify the use of defensive force so long as one’s theory of imminence is sufficiently elastic. There is no a priori reason that imminence has to be defined in seconds or minutes.

There are good reasons to support each proposal. For the moment, ultimate resolution of this theoretical dilemma need not be resolved here. In that sense, the general issue can be understood from two distinct perspectives: the imminent threat posed by a terrorist attack, including the bomber, planner and financier, or the immediate necessity of engaging a particular target with defensive force at a discrete moment in time. The first perspective focuses on the temporality of the threat, while the second perspective focuses on the temporality of the defensive response. A targeted killing/drone policy can be justified under either model. What matters is the conclusion that defensive force can be justified against more than a suicide bomber engaged in the physical act of detonating his explosives.

However, limits must be imposed on the implementation of self-defense so that targeted killings will be applied in accordance with the rule of law. Not all threats are imminent and not all uses of defensive force are immediately necessary. Some threats might be uncertain or merely hypothetical, while the supposed closing of a window of opportunity to exercise defensive force might be illusory. Each issue will affect how decision-makers view the balancing of individual rights and national security in various ways. In addition, these different types of threats will have different impacts on key interests and principles, such as collateral damage, the rule of law, and the preservation of civil liberties. In order to grant these interests sufficient weight, targeted killing will—or certainly should—be used only in response to threats that are imminent rather than distant, or only when the response is immediately necessary. Finally, the imminence of the threat and the immediacy of the response are not the end of the process—the threat must also pose a sufficiently grave danger of the loss of innocent life. Here, the distinction raised above between a suicide bombing at a pizza parlor and the throwing of Molotov cocktails is instructive: the latter does not pose the same danger of harm to the same number of individuals.

The essence of the decision to authorize a targeted killing depends on a process that allows for a careful analysis of both the nature of the threat, the identity of the threat, the imminence of the threat, and the immediate necessity of the response—all factors that invoke the full range of considerations elucidated in this chapter. The following operational considerations also play a role: whether the individual is detainable, or whether it is possible to postpone detention until the plan reaches later stages of fruition in order to apprehend additional perpetrators. Trying to undertake that analysis in the absence of clear criteria and guidelines for decision-making can lead to decision paralysis or an incomplete consideration of critical issues. Therefore, the following section summarizes the proposed model for determining the nature of the threat, its imminence and the consequences of particular responses in particular legal and policy areas. The proposed model also addresses the relationship between counterterrorism measures available and the measure actually chosen and provides a matrix to evaluate whether the decision was appropriate.

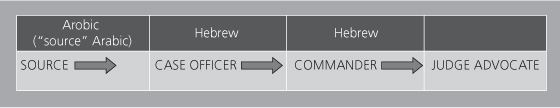

Threat analysis refers to the nature of the target and his or her planned activities and attacks. Assessing where the information about the target and the planned attack comes from is an equally vital aspect of the decision-making process. Thus, source analysis must be a major component of the criteria-based approach. The intelligence community receives information from three different intelligence sources: human sources (that is, individuals who live in the community about which they are providing information to a case officer who serves in the intelligence community); signal intelligence (that is, intercepted phone and email conversations); and open sources (that is, internet and newspapers). The responsibility of the intelligence community is to analyze the gathered information in an effort to develop an accurate picture. Targeted killing is largely dependent on the intelligence information received from a source; the recipient of the information is the case officer who is tasked with identifying a potential source and then cultivating that individual over a period of time. The following chart explains the sequence:

One of the most important questions in putting together an operation is whether the received information is actionable; that is, does the information received from the source warrant an operational response? That question is central to criteria-based decision-making or at least to decision-making that requires objective standards for making decisions based on imperfect information. In other words, the goal is to enhance objectivity and minimize subjectivity in the decision-making process. However, it is essential that the information, including its source, be subjected to rigorous analysis. To that end, the following definitions of reliability, viability, relevancy, and corroboration (created to explain detention decisions) articulate the guidelines for determining whether the intelligence is sufficiently actionable.

First, is the intelligence reliable? In other words, do past experiences show the source to be a dependable provider of correct information? This requires that the case officer discern whether the information is useful and accurate and whether the source has a personal agenda or grudge against the identified target. Second, is the intelligence viable? In particular, is it possible that an attack could occur in accordance with the source’s information? Does the information provided by the source indicate that a feasible terrorist attack could be mounted? Third, is the intelligence relevant? To determine relevancy, the legal advisor must consider both the timeliness of the information and whether it is time-sensitive and requires an immediate counterterrorism measure. Fourth, can the intelligence be corroborated; that is, can another source (who meets the reliability test above) confirm the information in whole or in part?

With these criteria in mind, the advisor needs to consider both the source and the target and make more specific determinations. Consider the source first:

What is the source’s background and how does that affect the information provided? Does the source have a grudge or personal score to settle based on a personal or family relationship with the target?

What are the risks to the source if the target is killed? Source protection is essential to continued and effective intelligence gathering. Protecting the source is essential both with respect to that source and additional—present or future—sources.

What are the risks to the source if the intelligence is made public? This factor is relevant for selecting the proper forum for trying suspected terrorists because a civilian trial may require public disclosure of the evidence.

Now consider the target:

Who is the target of the source’s information? What is the person’s role in the terrorist organization? How would his or her detention affect that organization, short-term and long-term alike? What insight can the source provide regarding impact? For example, in the suicide-bombing infrastructure there are four distinct actors: the bomber, the logistician, the planner and the financier. Determining the legitimacy of the target (for a targeted killing) requires that one ascertain the potential target’s specific role in the infrastructure. Subject to the two four–part tests above, the following four actors are prima facie legitimate targets. First, the planner is a legitimate target 24 hours a day, seven days a week, precisely because the planner is the mastermind who sits atop the chain of command and directs the entire operation. Second, the bomber is a legitimate target, but arguably only when engaged in the operation. The bomber engages in terrorist activity occasionally but might very well return to civilian life at other points in time, at which point he could regain protected status. Third, the logistician is a legitimate target when involved in all aspects of implementing a suicide bombing but, unlike the planner, is not a legitimate target when not involved in a specific, future attack. The warrant for this conclusion is that the logistician is not the mastermind of the operation and, in fact, is much closer to the bomber than the planner. The essential difference between the logistician and the bomber is that the logistician’s support of the operation does not involve carrying the bomb; both are, in a sense, providing operational support. Fourth, the financier is a legitimate target when involved in wiring money or laundering money, both of which are essential for terrorist attacks. However, there remains significant room for debate and discussion regarding the nature and significance of the financier’s contribution to the terrorist plot. To that extent, the question is whether the financier is more akin to the bomber and the logistician on the one hand, or the planner on the other hand. Arguably, given the centrality of the financier’s role, the correct placing is between the logistician and planner. The financier’s contribution is usually more significant and essential than the mere logistician, in the sense that nothing in the operation happens without funding. That places the financier one step below the mastermind who has ultimate control over the operation.

What are the costs and benefits if the targeted killing is delayed? How time-relevant is the source’s information? Does it justify immediate action? Or, is the information insufficient to justify a targeted killing but significant enough to justify other measures, including detention?

What is the nature of the suspicious activity? Does the information suggest involvement in significant acts of terrorism justifying immediate counterterrorism measures? Or is the information more suggestive than concrete? In addition, if the information is indicative of minor (not harmful) possible action, effective counterterrorism might suggest additional information-gathering—from the same or additional source—before authorization of targeted killing.

What information could the target provide if he was detained and interrogated rather than killed? Does the individual possess information—to varying degrees of specificity—relevant to future acts of terrorism?

In a targeted killing decision, three aspects of the decision stand out: (1) can the target be identified accurately and reliably?; (2) does the threat the target poses justify an attack at that moment or are there other alternatives?; and (3) what is the extent of the anticipated collateral damage? A criteria-based decision-making process must therefore amass, assess and analyze the information necessary to make these determinations effectively.

The larger questions force us to consider the legality and morality of the policy and of its application in specific cases. In examining both legality and morality, decision-makers must avoid falling into the pitfall of decision by routine. There is, perhaps, nothing more dangerous than decision-makers who fail to inquire into considerations that extend beyond mere operational factors. That is not to minimize the complicated reality of operational decision-making, but simply to emphasize that additional questions must be asked in the context of criteria-based operational counter terrorism.

In that vein, my decision in the situation memorialized above—whether right or wrong—regarding the information the source provided to the case agent, the case agent gave to the commander, and the commander conveyed to me, was based on four characteristics. First, I was influenced by the commander’s interpretation of that information and his framing of the information, both how he initially framed the dilemma and his responses to my questions based on the checklist above. Second, my decision was affected by interpretation and classification of the answers into three distinct categories: legal, moral and operational. Third, my pre-existing personal and professional skills, as well as my previous experiences in these operations, all had an influence in the outcome. And finally, my understanding of the targeted killing policy and my frame of reference as a senior officer in the IDF, including my involvement in the implementation of the Oslo Peace Process, inevitably played a role in the decision. These personal factors are necessarily in the background of any decision-making process. To suggest otherwise is to profoundly overestimate the capacity of individuals to form all-things-considered judgments from a third-person point of view. In the absence of rigorous criteria for decision-making, these factors can degenerate into wholly subjective and irrational decisions. But with a rigorous and detailed criteria-based decision-making process, the inherent subjectivity of individual decision-making can be transformed from a source of error to a potential benefit. In other words, the legal advisor can use his or her extensive experience to augment the decision by framing that experience through the explicit criteria that have been determined in advance. The goal of this chapter has been to offer a prolegomenon to codifying that process.

Criteria-based decision-making enables decision-makers to operationalize counterterrorism policy within a framework of legal and moral principles, both of which are essential to effective and legal counterterrorism. While self-defense is a recognized principle in international law, it is not unlimited. Moreover, the grave risks of terrorism threaten to overrun any decision-making process relying on intuition and unconstrained discretion: everything and everyone will appear to be a severe and imminent threat in the heat of the moment. Rather, operational counterterrorism conducted in accordance with the rule of law requires the nation-state to engage in self-imposed limits when it conducts defensive operations. The criteria-based rational decision-making model proposed in this chapter significantly enhances operational counterterrorism that achieves two critical goals: engaging the legitimate target and minimizing collateral damage. Adoption of a checklist approach greatly facilitates the conduct of drone policy/targeted killing in accordance with the principles of international law. By developing a sophisticated mechanism to weigh and measure the reliability of intelligence, the decision-maker will be able to determine whether an individual is truly a legitimate target and whether circumstances justify engaging the identified individual. This facilitates lawful and effective targeted killing; at its core, the policy will be based on a process predicated on criteria, thereby significantly enhancing lawful aggressive self-defense.