St Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City (pictured) was by tradition the burial site of St Peter, the first Bishop of Rome and first in the line of papal succession. Here its dome rises above the facade begun in 1605 by the architect Carlo Maderna.

One thousand years ago and more, political instability was rife in Rome. At that time, the image of the papacy was everything from outlandish to weird to downright appalling. All kinds of dark deeds stuck to its name. Corruption, simony, nepotism and lavish lifestyles were only part of it, and not necessarily the worst.

![]()

Benedict IX (pictured), one of the most scandalous popes of the 11th century, was described as vile, foul, execrable and a ‘demon from Hell in the disguise of a priest’.

During the so-called ‘Papal Pornocracy’ of the early tenth century, popes were being manipulated, exploited and manoeuvred for nefarious ends by mistresses who used them as pawns in their own power games. With some justification, this era was also called the Rule of the Harlots.

So many popes were assassinated, mutilated, poisoned or otherwise done away with that when one of them disappeared, never to be seen again, it was only natural to scan a list of violent explanations to find out what had happened to him. Death by strangulation in prison was a frequent cause. Had the vanished pope been hideously mutilated and therefore made unfit to appear in public? Had he made off with the papal cash box? Or should the brothels and other houses of ill repute be searched to find out if he was there? Often, there was no clear answer and explanations were left to gossip and rumour.

By the ninth century, the papacy and the popes were the playthings of noble families.

One thing was certain, though: by the ninth century, the papacy and the popes were the playthings of noble families like the Spoletans, who controlled cities such as Venice, Milan, Genoa, Pisa, Florence and Siena, among others. Through their wealth and influence, and their connections with armed militias, these families formed what amounted to a feudal aristocracy. They were generally a brutish lot, willing to bring the utmost violence and cruelty to the task of seizing and controlling the most prestigious office in the Christian world. Once achieved, though, their newfound power could be ephemeral, for the reigns of some of their protégés were very short indeed. There were, for example, 24 popes between 872 CE and 904 CE. The longest reign lasted a decade and another four came and went within a year. There were nine popes in the nine years between 896 CE and 904 CE, as many pontiffs as were elected during the entire twentieth century. This meant, of course, that the papal See of Rome was in a constant state of uproar, as the struggle for the Vatican had to be fought over and over again.

Stephen VII was one of the short-lived popes, promising the House of Spoleto, in central Italy, a taste of papal power that turned out to be a brief 15 months in 896 CE and 897 CE. Stephen was almost certainly insane and his affliction appears to have been common knowledge in Rome. This, though, did not deter the Duchess Agiltrude from foisting him onto the Throne of St Peter in July 896 CE. Agiltrude, it appears, had a special task for Pope Stephen, which involved wreaking revenge on her one-time enemy, the late Pope Formosus.

Like most, if not all, legendary glamour heroines of history, Agiltrude was reputed to be very beautiful, with a sexy figure and long blonde hair. However that may be, she was certainly a formidable woman with a fearsome taste for retribution. In 894 CE, Agiltrude took her young son, Lambert, to Rome to be confirmed by Pope Formosus as Holy Roman Emperor, or so she expected. She found, though, that the venerable Formosus had ideas of his own. He preferred another claimant, Arnulf of Carinthia, a descendant of Charlemagne, the first of the Holy Roman Emperors. The pope realized that Agiltrude was not going to stand by quietly and watch as her son was displaced, and knowing well the turbulent temper of the Spoletans, he saw trouble coming. So, Formosus appealed to Arnulf for help.

Arnulf, for his part, had no intention of being forced to give way to an underage upstart like Lambert or his implacable mother. He soon arrived with his army, sent Agiltrude packing back to Spoleto and was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Formosus on 22 February 896 CE. The new emperor at once set out to pursue Agiltrude, but before he could reach Spoleto, he suffered a paralyzing illness, possibly a stroke. Pope Formosus died six weeks later, on 4 April 896 CE, reputedly poisoned by Agiltrude. By all accounts, he had been an admirable pope, well known for his care for the poor, his austere way of life, his chastity and devotion to prayer, all of them admirable Christian virtues – and remarkable – in an age of decadence, self-seeking and barbarism.

Stephen was almost certainly insane and his affliction appears to have been common knowledge in Rome.

Pope Formosus was rumoured to have been poisoned before his death in 896 CE, but he suffered horrific injuries afterwards. Several of his fingers were cut off and he was beheaded before being thrown into the River Tiber.

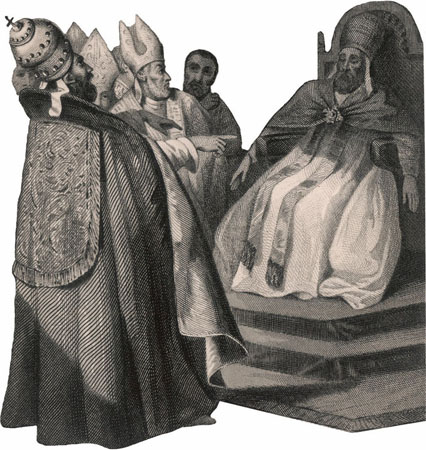

Pope John VIII (seated) gives a papal blessing to Charles the Bald, King of West Francia in northwestern France after his coronation as Holy Roman Emperor in 875 CE.

But whatever his virtues, Formosus could not entirely escape the poisonous atmosphere of violence and intrigue that permeated the Church in his time. It was all too easy to make enemies and so become exposed to their vengeance and bile. It was also possible that Formosus was too honest and outspoken for his own good. It was, for instance, an unwise move to oppose the election of Pope John VIII in 872 CE, particularly when Formosus himself had been among the candidates. It was bad policy, too, to have friends among Pope John’s enemies who were perennially plotting against him. They were so intent on destroying him that they sought help for their nefarious plans from the Muslim Saracens, who were the sworn enemies of Christianity.

This was an age when the enemies of popes had a habit of disappearing or ending up dead. The writing on the wall was easy to read, and when his plotter friends fled from the papal court, Formosus fled with them. This, of course, implied that he was one of the conspirators. As a result, he was charged with some lurid crimes, such as despoiling the cloisters in Rome, and conspiring to destroy the papal see. Formosus was punished accordingly. In 878 CE, he was excommunicated. This sentence was withdrawn, though, when Formosus agreed to sign a declaration stating that he would never return to Rome or perform priestly duties. In addition, the Diocese of Porto, in Italy, where Formosus had been made Cardinal Bishop in 864 CE, was taken from him.

Such accusations and penalties, made against an elderly man of proven probity and morality were clearly ludicrous and had all the appearance of a put-up job.

Such accusations and penalties, made against an elderly man of proven probity and morality were clearly ludicrous and had all the appearance of a putup job. Fortunately, all was later forgiven. After the death of John VIII in 882 CE, his successor as pope, Marinus I, recalled Formosus to Rome from his refuge in western France, and restored him to his Diocese of Porto. Nine years later, Formosus was himself elected pope and it was during his five-year tenure that he made a very serious mistake: he crossed Duchess Agiltrude and the House of Spoleto. He also made other enemies over his policies as pope, which included trying to eradicate the influence of lay (non-ordained) people in Church affairs.

Quite possibly, this was why the death of one of her enemies and the incapacity of the other were not enough for Agiltrude. She had in mind something much more dramatic and gruesome. Once Formosus’ successor as pope, Boniface VI, had gone, the way was clear for Stephen VII, the candidate favoured by Agiltrude and her equally malicious son Lambert, to step up to the plate and do their bidding.

In January 897 CE, Stephen announced that a trial was to take place at the church of St John Lateran, the official church of the pope as Bishop of Rome. The defendant was Pope Formosus, now deceased for nine months, for whom Stephen had developed a fanatical hatred. Stephen was a thoroughly nasty piece of work but the source of his hatred is not precisely known: it is possible that just being a member of the House of Spoleto relentlessly prodded along by the fearsome Agiltrude was enough. Even so, hatred, however obsessive, could not easily explain the horrors that featured in the posthumous trial of Pope Formosus some time in January 897 then nine-months dead.

Pope Stephen VII put on a very dramatic show at the ‘trial’ of the dead Pope Formosus, whose mouldering corpse was dug up from its grave to play its grisly part in the Cadaver Synod of 897 CE.

The dead pope was not tried in his absence. At Agiltrude’s prompting, Formosus – or rather his rotting corpse, which was barely held together by his penitential hair shirt – was removed from his burial place and dressed in papal vestments. He was then carried into the court, where he was propped up on a throne. Stephen sat nearby, presiding over the ‘trial’ alongside co-judges chosen from the clergy. To ensure they were unfit for the task, and merely did what they were told, several co-judges had been bullied and terrorized and sat out the proceedings in a lather of fear. At the trial, the charges laid against Formosus by Pope John VIII were revived. For good measure, Stephen added fresh accusations designed to prove that Formosus had been unfit for the pontificate: he had committed perjury, Stephen claimed, coveted the Throne of St Peter and violated Church law.

This illustration of Pope Stephen VII interrogating the dead Pope Formosus portrays the corpse of the one-time pontiff in a rather better condition than it would have been in reality: Formosus had died several months previously.

His corpse was stripped of its vestments and dressed instead in the clothes of an ordinary layman. The three fingers of Formosus’ right hand, which he had used to make papal blessings, were cut off.

Stephen’s behaviour in court was extraordinary. The clergy and other spectators in court were treated to frenzied tirades, as Stephen mocked the dead pope and launched gross insults at him. Formosus had been allowed a form of defence in the form of an 18-year-old deacon. The unfortunate young man was supposed to answer for Formosus, but was too frightened of the raving, screaming Stephen to make much of an impression. Weak, mumbling answers were the most the poor lad could manage.

Formosus was buried yet again, this time in an ordinary graveyard. Like the rescue itself, the burial had to be kept secret.

Inevitably, at the end of the proceedings, which came to be called, appropriately, the Cadaver Synod, Formosus was found guilty on all the charges against him. Punishment followed immediately. Stephen declared that all of the dead pope’s acts and ordinations were null and void. At Stephen’s command, his corpse was stripped of its vestments and dressed instead in the clothes of an ordinary layman. The three fingers of Formosus’ right hand, which he had used to make papal blessings, were cut off. The severed fingers – or rather what was left of them after nine months of decay – were handed over the Agiltrude who had watched the proceedings with open satisfaction. Finally, Pope Stephen ordered that Formosus should be reburied in a common grave. This was done, but there was a grisly sequel. Formosus’ corpse was soon dug up, dragged through the streets of Rome, tied with weights and thrown into the River Tiber.

Formosus had been revered by many of the clergy and he was popular with the Romans and, before his election in 891 CE, many had rioted at the prospect of another pope being chosen instead. There was, therefore, no shortage of helpers when a monk who had remained faithful to the dead pope’s memory asked a group of fishermen to aid him in retrieving Formosus’ much misused remains. Afterwards, Formosus was buried yet again, this time in an ordinary graveyard. Like the rescue itself, the burial had to be kept secret. If Formosus’ enemies – particularly Pope Stephen and Agiltrude – had learnt of it, it was likely that the body of the dead pope would have been desecrated yet again.

The Cadaver Synod, known more graphically by its Latin name Synodus Horrenda, prompted uproar and outrage throughout Rome. This was underlined in the superstitious popular mind when the Basilica of St John suddenly fell down with a thunderous roar just as Pope Stephen and Agiltrude emerged from the church of St John Lateran at the end of the ‘trial’. The fact that the Basilica had long ago been condemned as unsafe was less convincing than the idea that the collapse was a sign of God’s displeasure. Before long, in much the same vein, rumours arose that the corpse of Pope Formosus had ‘performed’ miracles, an ability normally ascribed only to saints.

Theodore II reigned as pope for only twenty days, but that was long enough for him to restore the good name of his much abused predecessor, Formosus.

Stripped of his splendid papal vestments and insignia, he was thrown into prison, where he was strangled.

The widespread disgust at the savagery of the proceedings, and its ghastly sequel, convinced many clergy that if anyone was unfit to be pope it was Stephen VII. An element of self-interest also featured in the wave of hostility aroused by the Synod. Many clergy who had been ordained by Formosus were deprived of their positions when Stephen nullified the dead pope’s ordinations.

Hostility soon translated into action. In August 897 CE, eight months after the Cadaver Synod, a ‘palace revolution’ took place and Stephen VII was deposed. Stripped of his splendid papal vestments and insignia, he was thrown into prison, where he was strangled. This, though, was by no means the end of the days when the popes and the papacy were mired in disgrace. For one thing, Agiltrude was still around and active and, wherever she was, there was bound to be trouble. Agiltrude was enraged at the murder of her protégé Pope Stephen and moved in fast to restore the influence that had been killed off with him. But she had no luck with the new pope, Romanus, who was placed on the papal throne in 897 CE but remained there for only three months. Romanus, it appears, fell foul of one of the factions at the papal court that was opposed to Agiltrude and the House of Spoleto. Afterwards, the hapless former pope was ‘made a monk’ an early medieval European euphemism that meant he had been deposed.

Sergius … had Formosus’ corpse beheaded and cut off three more of his fingers before consigning him to the River Tiber once more.

Romanus’s successor, Pope Theodore II, was even less fortunate, but at least he lasted long enough to do right by the much-abused Formosus. Theodore ordered the body of the late pope reburied clad in pontifical vestments and with full honours in St Peter’s in Rome. He also annulled the court where the Cadaver Synod had taken place and invalidated its verdicts and decisions. Much to the relief of the clergy dispossessed by Stephen VII, Theodore declared valid once again the offices they had once received from Formosus. It was as if the Cadaver Synod and the lunatic Pope Stephen had never existed. Unfortunately, however, it brought Theodore few, if any, rewards. His reign lasted only 20 days in November 897 CE, after which he mysteriously died. The following year, however, future trials of dead persons were prohibited by Theodore’s successor, Pope John IX.

Ten years later, Sergius III, who was elected pope in 904 CE, dug up Pope Formosus and put him on trial all over again. Sergius, then a cardinal, had been a co-judge at the Cadaver Synod in 897 CE and became infuriated when the guilty verdict was overturned. This time, Sergius restored the guilty judgement and added some ghoulish touches of his own. He had Formosus’ corpse beheaded and cut off three more of his fingers before consigning him to the River Tiber once more. To emphasize his message, Sergius ordered a flattering epitaph for Stephen VII be inscribed on his tomb.

Not long afterwards, Formosus’ headless corpse surfaced again when it became entangled in a fisherman’s net.

Not long afterwards, Formosus’ headless corpse surfaced again when it became entangled in a fisherman’s net. Retrieved from the Tiber for a second time, Formosus was returned once more to St Peter’s church. Sergius had, of course, contravened the prohibition on posthumous trials declared by John IX so his actions were essentially invalid. Nevertheless, a public statement of Formosus’ innocence had to be made and both he and his work were formally reinstated yet again.

The chief instigator of the original Cadaver Synod, Agiltrude, was still alive when Formosus was exonerated for a second time but her position – and her power – had radically altered because, through the extraordinary antics of Stephen VII, she had triumphed over the dead pope in 896 CE. But she had a weakness. Agiltrude’s power, while considerable, was essentially second-hand, relying on puppets like Pope Stephen who could be manoeuvred into the positions she wanted them to occupy and from there implement her policies. Also important in Agiltrude’s armoury were certain family relationships that gave her the high status she enjoyed from the positions occupied by her husband, Guy of Spoleto, and after him, by their son, Lambert. When Guy died on 12 December 894 CE, Agiltrude instantly lost her standing as Duchess of Spoleto and Camerino, Queen of Italy and Holy Roman Empress. There was still some kudos to be had from Lambert’s elevation to all these titles, but he died before his mother in 898 CE and Agiltrude’s last family link with power disappeared.

Agiltrude died in 923 CE, but by that time two other women had discovered another way into the corridors of papal power in Rome. They were Theodora and her daughter Marozia, both of them the mistresses of popes. Theodora was described as a ‘shameless strumpet’ and her two daughters, Marozia and the younger Theodora as possessing reputations not ‘much better… than their mother’.

Neither the elder Theodora nor Marozia halted the rapid turnover that had become a regular feature of the papacy. If anything they exacerbated it. In the first years of the tenth century, short pontificates of a year or less persisted, and so did the violent deaths of popes that reflected the ongoing struggle for power. Others managed to survive for a year or two but rarely much more. In fact, popes succeeded one another with such rapidity that papal servants made a handsome profit selling off their personal accoutrements and furnishings.

Short pontificates of a year or less persisted, and so did the violent deaths of popes that reflected the ongoing struggle for power.

But petty theft was very small beer compared to the corruption, licentiousness and venality of this period, which was known as the ‘papal pornocracy’ or the ‘Rule of the Harlots’ by those who, with good reason, believed that the papacy was now in the hands of whores. Like the puppets whose strings were so diligently pulled by Agiltrude, the pornocracy popes were eager partners in the decadence and immorality that characterized this shameless – and shameful – era.

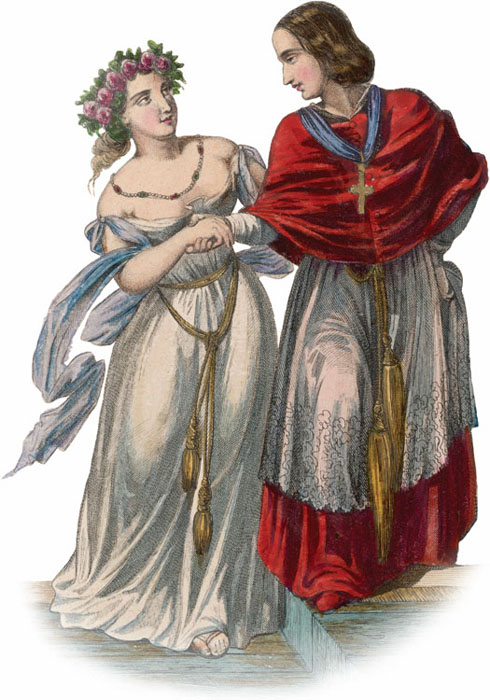

A portrait of Marozia, the ‘shameless strumpet’ who schemed her way to power in Rome in the 10th century CE and matched her lover, Pope Sergius III, for licentiousness and vice.

The tenth-century Lombard historian, Bishop Liutprand of Cremona, was virulently anti-Roman and anti-papal. However, rather more than a grain of truth was in the mix when he wrote in his Antapodosis, a history of the papacy from 886–950 CE:

They hunted on horses with gold trappings, had rich banquets with dancing girls when the hunt was over, and retired with (their) whores to beds with silk sheets and gold embroidered covers. All the Roman bishops were married and their wives made silk dresses out of the sacred vestments.

Bishop Liutprand branded Theodora and Marozia as ‘two voluptuous imperial women (who) ruled the papacy of the tenth century’. Theodora, he maintained, was ‘a shameless strumpet… at one time… sole monarch of Rome and – shame though it is to write it – exercised power like a man.’ Theodora’s second daughter, another Theodora, did not escape censure for she and her sister, Liutprand continued, ‘could surpass (their mother) in the exercises that Venus loves’. This was hard on the younger Theodora who, it appears, led a blameless life devoted to good works, but Liutprand’s assessment of Marozia was much nearer the mark. For one thing, Marozia kept an establishment on the Isola Tiberina, an island in the middle of the River Tiber where modesty and morality were unknown.

Marozia kept an establishment on the Isola Tiberina, an island in the middle of the River Tiber where modesty and morality were unknown.

Turning to Theodora, Liutprand described in detail how she seduced a handsome young priest and obtained for him the bishopric of Bologna and the archbishopric of Ravenna. It seems, though, that Theodora later regretted her generosity. She soon missed her youthful lover and in order to have him near her so that she could be his ‘nightly companion’, she summoned him to Rome. In 914 CE, she made him pope as John X. He was probably the father of Theodora’s younger daughter.

Pope John, it appears, fitted well into the pornocratic ethos he found in Rome. He was a skilful military commander who fought and won battles against the Muslim Saracens. But he blotted his copybook, and did it with indelible ink, through his nepotism, the enrichment of his family and his almost complete lack of principle. Far from being grateful to Theodora for his elevation to the most exalted of Church offices, John deserted her once he had set eyes on the delectable young daughter of Hugh of Provence, the future king of Italy.

Like Agiltrude, Marozia was motivated by the same blind hatred, the same remorseless urge for retribution and the same drive to prevail at all or any cost.

But Theodora’s daughter Marozia was not best pleased at the election – or rather the engineering – of John X onto the Throne of St Peter and she resolved to thwart both him and her mother with a candidate of her own: another John, her illegitimate son by Pope Sergius III, who was born in around 910 CE. When John X became pope, Marozia’s son was only about four years old, a trifle young for the pontificate, even in early medieval times when teenage popes were not unknown.

Marozia, however, had the time to brew her plans while she waited. She had watched the Duchess Agiltrude in action at the Cadaver Synod and afterwards took her as her role model. Like Agiltrude, Marozia was motivated by the same blind hatred, the same remorseless urge for retribution and the same drive to prevail at all or any cost. And like so many people bent on revenge, Marozia had a long memory that kept past wrongs vividly alive.

In Marozia’s eyes, revenge was due at the outset for the death of her first husband, Count Alberic of Lombardy, whom she had married in 909 CE. Alberic was a born troublemaker, reared in a family skilled in the dark arts of intrigue, murder, adultery, simony and almost every other profanity known to decadence. The Counts of Lombardy were, in addition, adept at making popes, having put seven members of their family on the Throne of St Peter after seizing control of papal elections.

The Muslim Saracens, the deadly enemies of Christian Europe, are shown here landing in Sicily, which they conquered in 827 CE. Pope John X led a Christian army to repel the invaders.

Marozia, no mean exponent of these abuses herself, quickly recognized her husband’s potential and the ambition his upbringing had bred in him. She set about encouraging him to challenge Pope John X and march on Rome with a view to seizing the pontiff, and his job with him. For once, though, Marozia made a serious misjudgement. John X was no pushover like so many puppet popes in the ‘Rule of the Harlots’ but a tried-and-tested military leader with a notable victory to his credit.

In 915 CE, John had taken to the field in person at the head of the army of the Christian League and smashed the Muslim Saracen forces in a battle close to the River Garigliano, some 200 kilometres north of Rome. Nine years later, Marozia succeeded in persuading Alberic to seize Rome and, probably, unseat Pope John X. But when Alberic marched on the Holy City, his defeat at the battle of Orte in Lazio, central Italy, was just as resounding. Alberic was killed and his body mutilated. For good, ghoulish measure the victorious pope forced Marozia to view what was left of her husband, a horrible experience she never forgot or forgave.

At the same time, she felt obliged to put her revenge on hold, for her mother Theodora was still alive. Perhaps out of a latent respect for Theodora or maybe fearing a backlash from her supporters, Marozia seems to have made no move against John, for the moment at least. Meanwhile, in 924 CE, Pope John stoked Marozia’s desire for revenge even further. He allied himself with the former Hugh of Provence, the new King of Italy, so endangering Marozia’s power in Rome.

Two years later, in 926 CE, Marozia married a second and highly influential husband, Guido, Count and Duke of Lucca and Margrave, or military governor, of Tuscany. This marriage greatly strengthened Marozia’s position, as did the death in 928 CE of Theodora. There were, of course, rumours that Marozia had poisoned her and she was certainly ruthless enough to do away with her own mother. Nevertheless, Theodora’s death facilitated Marozia’s revenge, for, without his former patroness, Pope John X became more vulnerable. Together, Marozia and her husband Guido saw to it that he soon became even more so.

Pope Leo VI was one of the many short-lived popes of the age of pornocracy. He was elected around June 928 CE and reigned for only seven months. Little is known about him, either good or bad, apart from the fact that he is thought to be one of several pontiffs buried in St Peter’s Basilica.

For good, ghoulish measure the victorious pope forced Marozia to view what was left of her husband, a horrible experience she never forgot or forgave.

The couple arranged the murder of John Petrus, Prefect of Rome, who was Pope John’s brother. Petrus had received favours and lucrative offices from John that furious Roman nobles believed were not his due but were owed to them. However, there was more to the killing of Petrus than pure revenge. He got in the way of Marozia’s plans by proving a stalwart support for his brother, and a valuable aide in navigating safely the currents of intrigue, violence and betrayal that marked the troubled waters of the tenth-century papacy. But with John Petrus out of the way, the safeguards he provided vanished with him and it was then a simple matter of arresting John and throwing him into prison in the Castel Sant’Angelo. He soon died, either smothered in bed according to Liutprand or a victim of anxiety – for which read stress – in a version of John’s death by the French chronicler Flodoard.

On the face of it, Marozia now reigned supreme among the power brokers and pope-makers of Rome, but this impression was deceptive because everything Marozia had worked and schemed for was about to disintegrate. She set up two more puppet popes. The first was Leo VI, who came and went in a single year, 928 CE and, it was rumoured, was poisoned by Marozia after a reign of only seven months. His successor was Stephen VIII, who fared a little better, reigning from 928 CE to the early months of 931 CE. This may have appeared to conform to the typical sequence of events, with short-lived popes succeeding each other and then dying or disappearing. However, behind this familiar routine, Marozia was biding her time until her illegitimate son John reached an age when she could make him pope in his turn. John was 21 years of age, just about old enough to assume the papal crown, when his mother at last achieved her ambition and created him Pope John XI in 931 CE.

Marozia … set up two more puppet popes… However, behind this familiar routine, Marozia was biding her time until her illegitimate son John reached an age when she could make him pope in his turn.

Marozia’s second husband had died in 929 CE. Three years later, John XI facilitated Marozia’s third marriage to her old foe, King Hugh of Italy, who, as the late Guido’s half-brother was also her brother-in-law. This relationship contained one of two impediments to the marriage for, under Church law, marriage between in-laws was illegal and tantamount to incest. Another obstacle was the fact that Hugh already had a wife, but that was easily dealt with as Pope John arranged a quickie divorce. The pope also presided at the wedding, lending it an air of legitimacy that, strictly speaking, it did not possess.

John had steered his mother through otherwise impenetrable difficulties, but any satisfaction this gave Marozia was very short-lived. Since her triumph over the late John X, she had reckoned without her second, legitimate, son whose father had been Marozia’s first husband Alberic, Count of Tuscany. The young Alberic II, intensely jealous of his elder half-brother and the favour their mother had shown him, soon demonstrated how true he was to the legacy of wickedness his ancestry had given him. Alberic was no friend of his mother’s third husband either, and lost no time displaying his dislike. The marriage ceremony was scarcely over and the guests were seated for the wedding breakfast when Alberic grossly insulted King Hugh. Hugh responded in kind, and the exchange of abuses moved on to violence when the King slapped Alberic for being clumsy.

Alberic was incandescent at this public humiliation and swore revenge. What Alberic did next may also have been motivated by rumours that King Hugh intended to have him blinded – a common means in early medieval times for incapacitating rivals while leaving them alive to suffer.

This relationship contained one of two impediments to the marriage for, under Church law, marriage between in-laws was illegal and tantamount to incest.

Hugh and Marozia had been married only a few months when Alberic roused an armed mob, worked them up into a vengeful fury and advanced on the Castel Sant’Angelo, where the couple were staying. They were rudely awakened by the commotion outside and Hugh, fearing he would be lynched, leapt out of bed and made his escape. Wearing only his nightshirt, he hid himself in a basket and was carried to safety by servants. He shinned down the city walls by means of a rope and fled, leaving Marozia to face her vengeful son alone. Alberic’s vengeance was truly terrible. He imprisoned his mother in the deepest underground level of the Castel Sant’Angelo, and it is doubtful she ever saw daylight again. She was then 42 years old, still beautiful and fascinating, but now she was set to moulder away for the next 54 years into extreme old age.

The Castel Sant’Angelo, which stands on the right bank of the River Tiber, was one of the papal residences. The statue of an angel at the top gave the castle its name. It was originally built as a mausoleum by the Roman Emperor Hadrian between 135 and 139 CE.

Alberic … imprisoned his mother in the deepest underground level of the Castel Sant’Angelo. She was then 42 years old.

Meanwhile, Alberic threw his bastard half-brother, Pope John XI, in jail while he consolidated his power. Once safely installed as ruler of Rome, Alberic released John from prison, but had no intention of setting him free. Instead, he placed his half-brother under house arrest in the church of St John Lateran. Almost all of John’s powers as pope were removed from him, leaving him only the right to deliver the sacraments. This, however, was no new experience for Pope John. All that happened was that he passed from the control of Marozia to the control of Alberic, who exercised both secular and ecclesiastical power in Rome.

John lasted four years under the tutelage of his younger brother before dying in 935 CE, leaving Alberic to emulate their mother and grandmother as creator of popes. Over the next 22 years, before his death at the age 43 in 954 CE, Alberic appointed four popes. And on his deathbed nominated his own illegitimate son, Octavian, aged 16, as their successor. Octavian duly became pope in 955 CE, taking the name of John XII, and was a complete and utter catastrophe.

The elaborate interior of the Church of St John Lateran, the Cathedral of the Diocese of Rome and the principal basilica of the Vatican. The ceremonial chair of the popes can be seen at the centre.

Pope John XII was so thoroughly dissolute it was rumoured that prayers were offered up in monasteries begging God to grant him a speedy death. There seemed to be no sin that John XII did not – or would not – commit. He ran a brothel at the church of St John Lateran where he put one of his own lovers, Marcia, in charge. He slept with his father’s mistress and his own mother. He took golden chalices from St Peter’s church to reward his lovers after nights of passion. He blinded one cardinal and castrated another, causing his death. Pilgrims who came to Rome risked losing the offering they made to the Church when the Pope purloined them to use in gambling sessions. At these sessions, John XII used to call on pagan gods and goddesses to grant him luck with throws of the dice. Women were warned to keep away from St John Lateran or anywhere else the pope might be, for he was always on the prowl looking for new conquests. Before long, the people of Rome were so enraged at John’s behaviour he began to fear for his life. His response was to rifle St Peter’s church for valuables and flee to Tivoli, some 27 kilometres (16 miles) from Rome.

Pope John XII. a thoroughly dissolute pontiff who ran a brothel at the Church of St John Lateran, is shown crowning the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I in 962 CE.

Pope John, still in exile at Tivoli replied that if the synod deposed him… he would excommunicate everyone involved, making it impossible for them to celebrate Mass or conduct ordinations.

John XII was doing so much damage to the papacy, which was still reeling from the crimes and sins of his predecessors, that a special synod was called to deal with him. All the Italian bishops and 16 cardinals and other clergy (some from Germany), convened to decide what to do with the ghastly young man who was their pontiff. They called witnesses and heard evidence under oath and finally decided on a list that added even more misdeeds to John’s already appalling record. Some of these were outlined in a letter written to John by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I of Saxony.

Everyone, clergy as well as laity accuse you, Holiness, of homicide, perjury, sacrilege, incest with your relatives, including two of your sisters and with having, like a pagan, invoked Jupiter, Venus and other demons.

Pope John, still in exile at Tivoli replied to Otto in terms so malevolent that fear permeated Rome. If the synod deposed him, John threatened, he would excommunicate everyone involved, making it impossible for them to celebrate Mass or conduct ordinations. In Christian terms, this was the worst possible penalty a pope could impose, for excommunication meant being thrown out of the Church, losing its protection and even endangering the immortal soul.

In spite of the threatened excommunication, the Emperor Otto deposed John and a new pope, Leo VIII, was put in his place. John, of course, would have none of this. When he eventually returned to Rome in 963 CE, his vengeance was infinitely worse than he had threatened. He threw out Pope Leo, but instead of excommunication, he executed or maimed everyone who sat in judgement on him at the synod. John had the skin flayed off one bishop, cut off the nose and two fingers of a cardinal and gouged out his tongue, and decapitated 63 members of the clergy and nobility in Rome.

Then, on the night of 14 May 964 CE, it seemed that all those prayers begging God to intervene and save Rome from its demon-pope had at last reached their divine destination. As a bishop named John Crescentius of Proteus later described it, ‘While having illicit and filthy relations with a Roman matron, (Pope John) was surprised in the act of sin by the matron’s angry husband who, in just wrath, smashed his skull with a hammer and thus liberated his evil soul into the grasp of Satan.’

… (Pope John) was surprised in the act of sin by the matron’s angry husband who, in just wrath, smashed his skull …

But the Church was not yet finished with the family of ‘harlots’ who had spawned nine of the most sinful popes ever to defile the name of the papacy. In 986 CE, 22 years after the dramatic death of John XII, Bishop Crescentius came to the Castel Sant’Angelo to see John’s mother, Marozia, who was now 96 years old. Marozia’s once ravishing beauty had crumbled into a bag of bones, her shrivelled flesh clothed in rags. The recently elected pope, John XV, had decided to take mercy on her, though his mercy took a form that only the medieval mind would have recognized.

Crescentius laid several charges against Marozia, including her conspiracy against the rights of the papacy, her illicit involvement with Pope Sergius III, her immoral life and her ‘plot’ to take over the world. Marozia was also compared to Jezebel, the arch-villainess of the Bible who also ‘dared to take a third husband’.

A portrait of Leo VIII, who was backed by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I but had to fight off a ferocious rival, John XII, before being acknowledged as the true pope. Leo’s reign lasted only eight months in 964 and 965 CE.

The belief that human wickedness could be caused by demonic possession was common in the early Middle Ages, so just in case Marozia’s demons were still present, she was exorcised. Now absolved from her sins and made fit to face her Maker, she died quickly after that. An executioner slipped into her cell and smothered her with a pillow ‘for the well-being’ it was said, of ‘Holy Mother Church and the peace of the Roman people’.

Marozia was now 96 years old. An executioner slipped into her cell and smothered her with a pillow…

However, the end of the pornocracy and the Rule of the Harlots was not the end of papal debauchery or the influential families who leeched off of it. The papacy had a very long way to go before it finally shed its notorious image as a tool of powerbrokers and parvenus who fronted vested interests whether royal, noble, political or commercial. In fact, it took another thousand years, until the nineteenth century, for the papacy to become the spiritual influence it was always meant to be and the Vicars of Christ no longer ranked high on the list of history’s greatest villains.

Pope John XII, once described as ‘a true debauchee and incestuous satanist’ is shown in a very un-papal pose, dancing with a scantily-clad woman, perhaps intended to portray his mother Marozia.