This portrait (pictured) of Pope Alexander VI, formerly Rodrigo Borgia, was painted by Juan de Juanes (1500–1579), often called the ‘Spanish Raphael’.

Power in the city-states of Renaissance Italy was frequently a family affair. And the families in question were truly formidable. The Visconti and Sforza of Milan, the Medici of Florence, the d’Este of Ferrara, the Boccanegra of Genoa or the Barberini, Orsini and della Rovere families shared some or, more often, all of the symptoms characteristic of their breed.

![]()

Alexander was probably the most controversial pope ever to have reigned, and remains infamous today.

They were intensely greedy for wealth and status, and could not resist enriching their relatives with high-ranking titles and the lavish lifestyles that went with them. Their power could frequently be secured by violence, murder and bribery and ruthlessness comparable only to the methods of the Italian families involved in organized crime centuries later.

The greatest power of all resided, of course, in the papacy and the immense influence the popes exerted over both the religious and the secular life of Catholic Europe. Several rich and famous families, including the Medici, the Barberini, the Orsini and the della Rovere, provided the Church with popes from their own ranks, but the most notorious of them all were the Borgias. The first of the two Borgia popes was the aged Calixtus III, formerly Alonso de Borja, who was elected in 1455.

From the start, Calixtus III excelled at nepotism. He set out to pack the Vatican bureaucracy with his relatives and place them in lucrative Church posts. Two of his nephews – Rodrigo was one of them – became cardinals in 1456. Such positions were normally occupied by mature or elderly men, but these two were had not yet reached 30, which both alarmed and astounded the College of Cardinals. They had agreed to the appointments under a false premise, expecting the elderly Calixtus to die soon, before the two young cardinals could be confirmed in their new positions. Instead, Calixtus stubbornly survived long enough for Rodrigo to be made Vice-Chancellor of the Church in 1457, which made him second in importance only to the pope himself. It also provided Rodrigo with the opportunity to acquire considerable wealth.

From the start, Calixtus III excelled at nepotism. He set out to pack the Vatican bureaucracy with his relatives and place them in lucrative Church posts.

Another nephew, Rodrigo’s brother and Calixtus’ special favourite, Pedro Luis Borgia was created Captain-General of the Church, in command of the papal armed forces. Pedro Luis was also made governor of 12 cities. It was a particularly powerful post, because these cities dominated important strongholds in Tuscany and the Papal States, the pope’s own territory in central Italy.

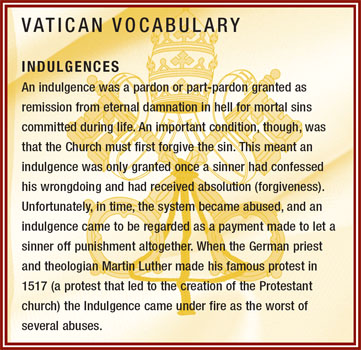

Just as shocking was the means Calixtus adopted to finance his crusade to liberate Constantinople from the Ottoman Turks who had conquered the capital of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 – a situation no self-respecting pope could tolerate. The Ottomans were Muslims and Constantinople, the most Christian of cities after Rome, could not be left in the hands of infidels. A crusade was arguably the most expensive expedition that could be undertaken, and to pay for it, Calixtus sold everything at his disposal, including gold and silver, works of art, valuable books, lucrative offices and grants of papal territories. He also put ‘indulgences’ up for sale – fees that Catholics paid to set aside punishments for their sins after death.

… Calixtus sold everything at his disposal, including gold and silver, works of art, valuable books, lucrative offices and grants of papal territories.

But the great papal sale was for nothing. The important rulers of Christian Europe, like the kings of France and Germany, were not interested in another holy war. When they declined to contribute troops and weaponry to the pope’s crusade that was the end of it. As a result, Constantinople was never retrieved for Christendom. Unsurprisingly, Pope Calixtus III became seriously unpopular in Rome. The situation was so grave that after he died in 1458, the Spanish commanders and administrators he had brought to the Vatican felt seriously threatened and fled from Rome in panic.

Rodrigo Borgia had to wait for 34 years and the reigns of four more popes before he came within reach of the Throne of St Peter. By then he was 61 years of age and had lost his youthful good looks and slim figure. But what he had retained was much more significant. As a young man, Pope Pius II, the successor to Rodrigo’s Uncle Calixtus warned him that his penchant for attending orgies was ‘unseemly’ and urged him to take care of his honour ‘with greater prudence’. It was a waste of papal breath: some 40 years later, nothing had changed. Rodrigo’s taste for debaucheries, which were euphemistically termed ‘garden parties’, was as keen as ever. He fathered eight children on three or four mistresses – the last when he was aged 61 – and, as he was once described, he remained ‘robust, amiable’, with a ‘wonderful skill in money matters’. The wealth this ‘wonderful skill’ brought him both before and after he became pope, was dazzling. One of his contemporaries wrote that

Calixtus III, pictured here with a cardinal, was also responsible for issuing a papal bull that gave permission for Portugal to engage in the transatlantic slave trade.

Rodrigo was not a man likely to follow the saintly path to papal acclaim. To him, the papacy was a business to be milked and exploited for gain, and a great deal of it.

… his papal offices, his numerous abbeys in Italy and Spain and his three bishoprics of Valencia, Porto and Cartagena, yield him a vast income and it is said that the office of Vice-Chancellor alone brings him in 8000 gold florins. His plate, his pearls, his stuffs embroidered with silk and gold and his books in every department of learning are very numerous… I need not mention the innumerable bed hangings, the trappings for his horses… nor the magnificent wardrobe, nor the vast amount of gold coin in his possession.

A portrait of Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) painted by his contemporary, the painter Perugino Pinturicchio (1454–1513).

This was not a man likely to follow the saintly path to papal acclaim. To him, the papacy was a business to be milked and exploited for gain, and a great deal of it. This was certainly the view of Francesco Guicciardini the historian and another contemporary of Rodrigo Borgia who wrote of him as pope:

There was in him and in full measure, all vices both of flesh and spirit… There was in him no religion, no keeping of his word. He promised all things liberally, but bound himself to nothing that was not useful to him. He had no care for justice since, in his days, Rome was a den of thieves and murderers. Nevertheless, his sins meeting with no punishment in this world, he was to the last of his days most prosperous. In one word, he was more evil and had more luck than perhaps any other pope for many ages before.

With a character reading like this, it followed that Rodrigo Borgia’s personal ambition knew no bounds and had lost none of its fire in old age. He deliberately set out to create a dynasty that had fingers in all the most vital political pies in Europe. He began as dishonestly as he meant to go on when the conclave of cardinals met to choose a successor to Pope Innocent VIII, who had died in 1492.

The papal states had issued their own currency since the ninth century. This is a coin from the reign of Pope Alexander VI.

Borgia’s chance of winning the election appeared bleak even before Innocent was dead. Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, who detested him, put in the poison by reminding the pope that Borgia was a ‘Catalan’, as Spaniards were commonly known in the Vatican, and was therefore unreliable. Rodrigo Borgia was there to hear this slur. He fought his corner with vigour and a range of insults so inflammatory that the rivals were on the brink of a fist fight before they were persuaded to back down out of respect for the dying pontiff.

Rodrigo Borgia’s personal ambition knew no bounds and had lost none of its fire in old age.

But already, behind the scenes, the wheeling, dealing and conniving were in full swing as the cardinals sought to outmanoeuvre each other and ensure victory for their personal candidates. Their choices had not been made on the basis of perception of the will of God or the workings of the Holy Spirit – the traditional criteria in papal elections – but on the wishes of the rulers in the city-states of Italy, each wanting a new pope sympathetic to their interests.

There was an enormous amount of money on the table for this exercise. For instance, King Ferrante of Naples offered a fortune in gold to buy the votes of cardinals willing to elect a pontiff who would advance Neapolitan interests at the Vatican. There was no holding back on the dirty tricks, either. For example, propaganda claiming that the Milanese were planning to subjugate the whole of Italy was spread around to scupper the chances of any candidate who came from, or was backed, by the city of Milan.

Rodrigo Borgia was not involved in any of this power play if only because, being a Spaniard, the other, Italian, cardinals deeply distrusted him. This, though, gave Borgia an advantage because it meant he was not tainted by the brute self-interest and venal machinations in which most of the other cardinals at the conclave were embroiled. Rodrigo also possessed another advantage that few, if any, of the others had. He was so wealthy he could dispense enormous bribes that could ‘buy’ votes at the conclave on a grand scale.

Rodrigo also possessed another advantage that few, if any, of the others had. He was so wealthy he could dispense enormous bribes that could ‘buy’ votes at the conclave on a grand scale.

In this 16th-century satire, coins fall like rain while Pope Alexander VI and his favourites stretch out hands to catch them.

A portrait of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza of Milan by an unknown Renaissance artist. Sforza was a hard-nosed politician, but his ambition for the papacy was no match for the wealth and greed of Rodrigo Borgia.

His chief rivals for the papal succession were Cardinal Ascanio Sforza of Milan and Cardinal Giuliani della Rovere, the latter being bankrolled to the tune of 200,000 gold ducats by the King Charles VIII of France. The Republic of Genoa contributed another 100,000 gold ducats to his campaign funds as well. Della Rovere and Sforza ran neck and neck for the lead in the first three ballots with Rodrigo Borgia coming third. But it was not a distant third, and the deadlock between the other two candidates enhanced Borgia’s chances of victory.

These bribes included bishoprics in Spain and Italy, extensive lands and estates, abbeys, castles and fortresses, governorships, Church offices, gold, jewels and treasure of all kinds.

Believing now that he could, after all, slip past della Rovere and Sforza and seize the prize, Rodrigo swamped the cardinals with offers he was sure they would find impossible to refuse. These bribes included bishoprics in Spain and Italy, extensive lands and estates, abbeys, castles and fortresses, governorships, Church offices, gold, jewels and treasure of all kinds.

Rodrigo reserved the most valuable temptations for Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, the Milanese candidate, to whom he offered his position as Vice-Chancellor and as an additional lure, his fabulous palace, which stood by the River Tiber opposite the Vatican. There were many magnificent mansions in Rome, but none excelled this one.

All this represented possibly the greatest bribe ever offered to a cardinal and Sforza managed to resist it for some five days before finally succumbing. One diarist recorded that, shortly afterwards, a train of four mules loaded with a large quantity of silver left Rodrigo’s palace and made its way through the streets of Rome to Sforza’s splendid but, by comparison much more modest, mansion.

With Sforza’s withdrawal from the papal race, the entire pro-Milanese faction switched their support to Rodrigo Borgia. Cardinal della Rovere, who had made it known that anyone would be preferable to another Borgia pope, was forced to swallow his words and vote for Rodrigo, if only as a gesture to save face. The other cardinals quietly pocketed their own rewards and marked their ballot papers in the same way. It was said that the last of them was a 96-year-old cardinal who was so far gone in senility that he barely knew where he was or what he was doing. Only five cardinals refused the incentives offered by Borgia. Those who accepted, of course, vastly outnumbered them.

The decision was finally reached after an all-night session. It was just before dawn on 11 August 1492 that Rodrigo Borgia, now Pope Alexander VI, dressed in papal vestments, appeared on the first-floor balcony of the Vatican before a large crowd to make the traditional pronouncement: ‘I am Pope and Vicar of Christ… I bless the town, I bless the land, I bless Italy, I bless the world.’

It was a tradition in Rome to mark papal elections with bouts of rioting and looting and the triumph of the second Borgia pope was no exception. Some 200 people died in the tumult before the result was announced and church bells rang throughout the city to mark the event. What was unique about this election, though, was the astonishment, rage and fear it provoked. ‘Now we are in the power of a wolf,’ commented Cardinal Giovanni di Lorenzo de’Medici of Florence, himself a future pope as Leo X, ‘the most rapacious, perhaps, that this world has ever seen. And if we do not flee, he will inevitably devour us all.’

The Palazzo Sforza Cesarini, given to Ascanio Sforza as a bribe to ensure he dropped out of contention for the papacy, still stands in a much altered state today.

Several others – Venetians, Ferrarans and Mantuans – vociferously cried ‘foul’ and there was talk of declaring the election corrupt and therefore void. Cheating on a truly shameless scale had, of course, taken place but the cardinals who fell for the Borgia bribes were giving nothing away and the new pope had himself been very careful to leave behind no proof that could be used against him. King Ferrante of Naples wept when he heard how the vast sums of money he had put up for his own candidate had failed to win the papal crown.

Cheating on a truly shameless scale had, of course, taken place but the cardinals who fell for the Borgia bribes were giving nothing away…

But it was not all sour grapes and some of the fears roused by the election of Alexander VI were not justified. Corrupt, immoral and faithless he might be, but the second Borgia pope also possessed qualities that enabled him to cope well with the greedy, materialistic, luxury-loving world of Renaissance Italy that would have flummoxed a more saintly, less worldly pontiff. During the reign of his uncle, Pope Calixtus and the four popes after him, Rodrigo Borgia had become a master diplomat, and administrator. He also knew how to use the amiable approach to personal relations rather than the ‘order from on high’ method to get what he wanted. Courtiers at the Vatican were agreeably surprised at the friendly, patient pope they had unexpectedly acquired. They noticed particularly Alexander’s willingness to attend to the problems of poor widows and other humble folk, and take action to ameliorate their troubles.

An anti-Catholic satire fom the 16th century, showing Alexander VI as the Devil wearing the triple crown of the popes.

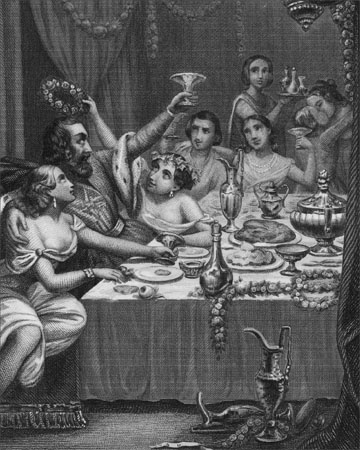

Even more amazing for a man who had surrounded himself in luxury and self-indulgence for several decades, was the careful budgeting Pope Alexander introduced into the Vatican. Once, not too long ago, the Borgia banquets held at Rodrigo’s Roman castle had been the talk of the town. They were so lavish they were said to excel the feasts of the emperors of ancient Rome: the richest of rich foods were served on solid gold plates accompanied by the finest wines drunk from extravagantly decorated goblets. Now, as pope, he reduced the Vatican menus from their former lavish size to one course per meal. This reduction was so drastic that invited guests started looking around for excuses to avoid papal dinners.

Alexander also sought ways and means of keeping his sex life – and its results – out of the public eye. He realized that his children could be an embarrassment to him now that he was pope.

Alexander also sought ways and means of keeping his sex life – and its results – out of the public eye. He realized, or claimed he realized, that his children could be an embarrassment to him now that he was pope, and at his coronation, he promised Giovanni Boccaccio, the ambassador from the Duchy of Ferrara that he would make sure they remained at a distance from the Vatican and Rome. This was probably impossible for a man as fond of his offspring as Pope Alexander was. Yet, though loving them intensely, he was also determined to use them and his other close relatives to cement his papal powerbase. As a result, the Boccaccio promise ran out after only five days when Alexander appointed his eldest son, Cesare Borgia, to the Archbishopric of Valencia. This made him, at 17 years of age, the primate of all Spain. The pope ignored the fact that young Cesare had not even been ordained a priest. In addition, Alexander appointed another of his sons, the 11-year-old Jofre to the Diocese of Majorca and made him an archdeacon of the cathedral at Valencia.

Cesare and Jofre, together with their sister Lucrezia and another son, Juan, were the children of Alexander’s first mistress, the three-times married Vannozza dei Cattani. Two more sons, Giralomo and Pier Luigi and another daughter, Isabella, were born to different mothers and the last, Laura, was the daughter of the pope’s final mistress, Giulia Farnese. In 1492, Giulia was in an awkward position and so was her lover, the new pope. As Rome’s greatest celebrity and one whose comings and goings were under constant scrutiny, Alexander could not, obviously, continue his habit of visiting Giulia at the Monte Giordano palace where he had installed her. A handy alternative was the palace of Santa Maria in Portico, which lay only a few metres from the steps of the church of St Peter in the Vatican.

Courtiers at the Vatican were agreeably surprised at the friendly, patient pope they had unexpectedly acquired.

The only problem was that a certain Cardinal Zeno already occupied Santa Maria in Portico. This was a minor difficulty, though, and was quickly removed, however, after the venerable cardinal was persuaded that his best interests would be served by loaning his palace to the pope. Giulia, who was pregnant, moved in with the pope’s daughter Lucrezia and Lucrezia’s nurse Adriana del Mila. Later on in 1492, Giulia gave birth to Laura. But the secrecy Alexander sought eluded him. The little girl, who grew to resemble her father closely, was soon the subject of gossip all over Europe. Diarists wrote of Giulia as ‘Alexander’s concubine’ and one satirist called her ‘the Bride of Christ’, an appellation that, it was said, amused her greatly.

Alexander VI’s family, including his extended family, had a particular value for him because Rome seemed to be full of his enemies. Among them were cardinals he had superseded at the conclave of 1492, their frustrated backers and the leading families of Rome who feared a strong man like Alexander and would have preferred a pontiff they could manipulate to do their bidding.

Pope Alexander gave a lavish party at the papal palace to celebrate the marriage of his daughter Lucrezia to her first husband Giovanni Sforza in 1493.

One satirist called her ‘the Bride of Christ’, an appellation that, it was said, amused her greatly.

Many Italians were suspicious of Alexander because he was a ‘Catalan’ and therefore a devious foreigner who, despite his years of service in the Vatican, was unlikely to do right by the papacy.

Zampieri Domenichino (1581–1641), who painted this picture of a woman with a unicorn, may have based her face on that of Giulia Farnese, Pope Alexander VI’s mistress.

The answer, as Alexander saw it, was to surround himself with his own relatives, the only people he could really trust. This nepotism was, of course, nothing new in the Vatican. Uncle Calixtus had been expert at it in his time and many other popes had seen the papacy as a prime opportunity to enrich and elevate their families by giving them titles, wealth and status otherwise beyond their reach. Even so, Alexander VI outdid them all. In his hands, the workings of this despotic, secretive and exclusive papacy came to resemble those of the Mafia – violent and exploitative where necessary, and propelled by fabulous amounts of money.

The appointments to high office of Alexander’s young sons Cesare and Jofre were only the start.

Pope Alexander VI’s disagreements with his son Cesare did not stop him appointing him a cardinal at the age of 18.

Alexander filled the Sacred College of Cardinals with Borgias and members of related families. The most important new cardinal was Cesare Borgia, although Alexander had to use trickery to get round the rule that only legitimately born candidates were eligible. Cesare was, of course, illegitimate but he was deftly ‘legitimized’ by his father who issued a papal bull declaring him to be the son of his mistress Vanozza de’Cattanei and her first husband, the late Domenico Giannozzo Rignano.

But another bull, issued on the same day, reversed the first and acknowledged the truth – that Pope Alexander was Cesare’s father. The second Bull was conveniently overlooked and Cesare duly qualified. But more than that, Pope Alexander insisted that all other cardinals of the Sacred College must be there to greet Cesare when he made his formal entry into Rome. It was unprecedented, but the pope was adamant. Predictably, Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere voiced the most strident protest, declaring that he would not stand by and let the College be ‘profaned and abused’ in this way. Nevertheless, this is precisely what he was forced to do and, with the other cardinals, had to offer to Cesare the homage the pope demanded of them.

The cardinals were already apoplectic with rage over admitting the pope’s bastard into their ranks when Alexander created another, similar, controversy: he proposed that Alessandro, the younger brother of Giulia Farnese, should also become a cardinal. This was seen as a reward for Giulia’s sexual services, which served to heighten the temperature at the College of Cardinals even further. Once again, though, Pope Alexander forced the appointment through, this time by threatening to replace all members of the College with more nominees of his own and make Alessandro a cardinal that way.

In addition, the Pope spread Borgia influence both inside and outside Italy by arranging advantageous unions for his children. The marriage of Alexander’s son Jofre to Sancia of Aragon, a granddaughter of King Ferrante of Naples, brought the pope a link with the royal family that ruled both Naples and Aragon. Jofre’s sister, Lucrezia Borgia, the only daughter of the pope and his mistress Vannozza dei Cattenei, was more a victim than the vicious purveyor of poison portrayed in so many Borgia legends. Her father, it appears, adored her, but that did not prevent him marrying her off three times for his own political advantage. Her first husband, Giovanni Sforza, who wed the 13-year-old Lucrezia in 1493, was supposed to bring Alexander a valuable connection with Milan. Giovanni, however, proved less than satisfactory. He was more attuned to French interests than to those of his father-in-law and persistently refused to perform the military service in the papal army Alexander required of him.

the Pope spread Borgia influence both inside and outside Italy by arranging advantageous unions for his children.

Alexander, aided and abetted by Cesare, decided to get rid of the unsatisfactory Giovanni. He was bullied into confessing something that was patently untrue, and totally mortifying for a Renaissance man to admit, that his marriage to Lucrezia had never been consummated, due to his own impotence. The fact that Lucrezia was pregnant at this time was conveniently overlooked. The divorce that followed opened the way for the pope to choose Lucrezia’s second husband, the handsome 17-year-old Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Bisceglie. Alexander had had designs on Naples for a number of years and Alfonso, whose Aragonese family exercised power over the city, seemed like the ideal means for implementing those ambitions.

Pope Alexander made his son Cesare a cardinal at the age of 18. This picture, painted by Giuseppe-Lorenzo Gatteri (1829-86), shows Cesare leaving the Vatican.

The marriage took place in 1498, but like Giovanni Sforza, before him, Alfonso soon ran out of usefulness. An assault by French and Spanish forces put an end to Aragonese control of Naples and so made young Alfonso disposable. In July of 1500, probably with the connivance of the pope, Cesare Borgia sent armed henchmen to attack Alfonso as he was walking past the church of St Peter in the Vatican. They failed to kill him this time, but Cesare completed the job, apparently in person, by strangling his brother-in-law as he convalesced. Lucrezia, a widow at the age of 20, was heartbroken, for she had genuinely loved Alfonso.

Portrait of a woman by Bartolomeo Veneziano (1502–1555), thought to be Lucrezia Borgia, eldest daughter of Pope Alexander. Lucrezia was used as a pawn by her father to conclude advantageous marriages.

Pope Alexander at last achieved what he wanted from a son-in-law when he arranged a third marriage for Lucrezia, with another, but much better, Alfonso.

Giovanni was bullied into confessing that his marriage to Lucrezia had never been consummated, due to his own impotence.

This was Alfonso d’Este, whose family ruled the city-state of Ferrara. At first, d’Este baulked at the idea of marrying into Lucrezia’s unsavoury family. This was not surprising when sensational gossip of all kinds, including allegations of murder, incest, immorality, debauchery and virtually every other crime it was possible to commit constantly surrounded the Borgias. Eventually, though, Alfonso came round and the couple were married on 30 December 1501. Unlike Lucrezia’s first two husbands, Alfonso and the d’Estes were fully in control of their city, which bordered on the northern boundary of the Papal States, and was able to lend power and influence to Alexander and all his successor pontiffs until the end of the sixteenth century. After that, Ferrara was absorbed by the Papal States.

But however generous he was towards his other children the lion’s share of paternal bounty went to Alexander’s favourite, his son Juan Borgia. In 1488, four years before Alexander became pope, the 11-year-old Juan had been gifted the Duchy of Gandia, the Borgia family estate in Spain, in the will left by his half-brother Pedro Luis. Juan’s older brother Cesare was infuriated to find himself passed over for the sake of a pampered sibling who was known in the Vatican as ‘the spoiled boy’ (and lived up to it for most of the time). Cesare was so enraged he swore that he would kill Juan, even though, as a member of the clergy, he was not eligible to take on Juan’s essentially secular honours. But Cesare was himself only 13 years old at the time and the threat was not taken seriously.

The tomb of Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Bisceglie, the second husband of Lucrezia Borgia, who was murdered by her brother Cesare in 1500.

Cesare Borgia sent armed henchmen to attack Alfonso. Lucrezia, a widow at the age of 20, was heartbroken.

The Duchy of Gandia was not the only bequest Juan received from Pedro Luis. He also inherited Pedro’s intended bride, Maria Enriquez de Luna. The 16-year-old Juan set sail for Spain and his Duchy in 1493 and did so in a grandiose style more suited to the travels of an emperor. His doting father had provided him with gold, jewels, silver, coin and a mass of other booty, which required the holds of four galleys to transport it from Italy to Spain. Gossips and other observers put it about that the family was in the process of shifting the Vatican treasures to Spain.

Gossips and other observers put it about that the family was in the process of shifting the Vatican treasures to Spain.

‘They say that he will return within a year,’ reported Gian Lucido Cattaneo, an envoy from the Italian city-state of Mantua ‘but will leave all that in Spain and come for another harvest.’

Pope Alexander also loaded his favourite son with instructions on how to behave properly, telling him to be ‘pious’ and ‘God-fearing’, to refrain from staying out late at night, to shun gambling and take care not to embezzle the revenues of his Duchy. Nevertheless, according to rumour, Juan quickly proved to be a chip off the old Borgia block once he was a safe distance away from his father. He spent his nights in taverns, drinking, gambling and consorting with prostitutes and, worst of all, neglecting his wife Maria. It was even whispered that Juan had been so busy carousing and debauching that he had not found the time to consummate his marriage. This was soon proved untrue for Maria Enriquez quickly became pregnant and Juan, in any case, denied the rest of the gossip as fictions put about by ‘people with little brain or in a state of drunkenness’.

A portrait painted by Bernardino di Betto, or Pinturicchio (1454–1513) which is said to depict Lucrezia Borgia.

But it did not take a great deal of brain or drink to recognize that the young Duke of Gandia had inherited his father’s extravagant tastes. One thing Juan failed to understand about Spain was that opulence and excessive show were unwelcome in a country that favoured ascetic Christianity and regarded the luxuriant splendours of Renaissance Italy with disdain.

Pope Alexander also loaded his favourite son with instructions on how to behave properly, telling him to be ‘pious’ and ‘God-fearing’…

Juan, of course, had never known anything but luxury and its gaudy manifestations, so that it was natural for him to create a palace in Gandia that contained magnificent furnishings and brilliantly ornate decor.

When complaints about his son’s inappropriate behaviour reached Alexander, he rushed off a furious letter demanding that Juan cultivate greater care for local sensibilities.

However, a while later, in 1497, it became apparent that Juan had roused enmities that needed to be answered by much more than mere grumbling. Despite his protestations, he was a Borgia through and through, leading a decadent life and displaying an excessively arrogant manner. ‘A very mean young man,’ was how one contemporary described him, ‘full of false ideas of grandeur and bad thoughts, haughty, cruel and unreasonable.’

Pope Alexander VI and Jacopo Pesaro, Bishop of Paphos paying their respects to St Peter in an oil painting by Titian (c.1485–1576), leader of the Venetian school of Renaissance art.

Late in the summer of 1496, Juan came to Rome to be installed by his father as Captain-General of the Church. This was a highly prestigious post that placed Juan in charge of the papal army, even though he had no military experience, training or talent for the task. There were far better qualified nobles in Rome, such as the prominent condotierre, Guidobaldo de Montefeltre, Duke of Urbino, to name only one. Naturally they were furious at being upstaged by a callow and overindulged youth. And their worst suspicions were confirmed. Juan’s immediate brief was to bring to heel the powerful but rebellious Orsini family who were backed by a strong French presence. After several attempts in which dozens of papal soldiers were needlessly sacrificed through Juan’s ineptitude, the Orsini were finally brought to heel and their French backers driven off.

The hero of the hour should have been Gonsalvo di Cordova, an aristocrat and renowned general known in his native Spain as El Gran Capitan (the Great Captain). It was di Cordova, nominally Juan’s ‘lieutenant’, who masterminded the final, victorious, siege and assault of the ‘Orsini wars’. However, Pope Alexander wanted his beloved Juan to take all the credit and gave him the place of honour at the celebration banquet. The infuriated di Cordova refused to take his seat and walked out. The pope, blinded by inordinate love of his favourite son, fooled himself that this hostility was due to jealousy of Juan, and planned new honours for him. One of his ideas was to make Juan King of Naples after the incumbent, Ferrante II, died in 1496. It was only when threatening noises reached him from King Ferdinand of Aragon that Alexander backed off.

a highly prestigious post placed Juan in charge of the papal army, even though he had no military experience.

However, favouring Juan did not account for all the ambitions of Alexander at this time. He was, in fact, aiming to use his son as a means of expanding Borgia power throughout Italy. As pope, Alexander already controlled the Papal States, which occupied a large swathe of central Italy. Although he had been thwarted in his plans to absorb Naples, he was able to use papal cities that lay within the Neapolitan boundaries – Benevento, Terracina and Pontecorvo – to make a sizeable new territory for Juan. When this move was announced in June of 1497, a wave of protest swept Rome. Alexander’s enemies did not find it difficult to guess its significance. It was, they believed, a preliminary move to absorb the Kingdom of Naples by more furtive means. There was, though, a terrible method by which this expansion, and any others Alexander had in mind, could be halted in its tracks – assassination.

Gonsalvo di Cordova, Duke of Terranova and Santangelo, was the Spanish general who made Spain the premier military power of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Pope Alexander was devastated when he heard how horribly Juan had been killed. It was said that he let out a great roar like an injured animal when he saw Juan’s bloated, muddied body. The diarist Johann Burchard, Master of Ceremonies to Pope Alexander, wrote:

The pope, when he heard that the duke had been killed and flung into the river like dung, was thrown into a paroxysm of grief, and for the pain and bitterness of his heart shut himself in his room and wept most bitterly.

Alexander refused to let anyone in for several hours, and neither ate nor drank anything for more than three days. In his overwhelming grief, he imagined that Juan had been killed because of his own sinful excesses. He said:

God has done this perhaps for some sin of ours and not because he deserved such a cruel death… We are determined henceforth to see to our own reform and that of the church. We wish to renounce all nepotism. We will begin therefore with ourselves and so proceed through all the ranks of the church till the whole work is accomplished.

It was the grief talking, of course. Alexander was too much of a dyed-in-the-wool sinner, too far gone in excess and pleasure to convert himself in the overnight manner he seemed to suggest. Instead, he reverted to type and to his long-established immoralities and his intrigues in politics. His cardinals and other clergy did not mind too much for they, too, were loath to give up their own pleasures.

The pope, blinded by inordinate love of his favourite son, fooled himself that this hostility was due to jealousy of Juan.

Juan was buried in the family chapel a few hours after he was found. He was accompanied to his grave by 120 torchbearers. As the procession reached the place on the shore of the River Tiber where the body was found, men of the Borgia’s own private army unsheathed their swords and swore vengeance on whoever had perpetrated the crime. Despite the offer of a generous reward, the murderer was never found, but there were plenty of suspects. One of the noble Roman families, deprived by Juan and his father of the honours they believed were their due, might have done the deed. In particular, Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, the great enemy of the Borgias, who had links with the Orsini family, could have contrived the killing.

Another possible culprit may have been closer to home, too close, in fact, for comfort. Pope Alexander had ordered an investigation shortly after the murder, but this was suddenly closed only three weeks later. It was never reopened. This mystery fed the speculation that surrounded Juan’s death and it was whispered that the investigation had already done its job and revealed a murderer whose name the pope did not want publicized. The most likely candidate, according to the gossip, was his son, Cesare Borgia, who had been one of the last to see Juan alive. Juan’s young widow, Maria Enriquez de Luna and her family seemed certain that Cesare had murdered his brother. Nine years after swearing to kill Juan, they believed, he had made his threat come true, and there appeared to be evidence to support this theory.

When the procession reached the place where the body was found, men of the Borgia’s own private army unsheathed their swords and swore vengeance.

For one thing, Cesare’s ruthless, rapacious nature and his penchant for intrigue were already well known. Murder, it was said, was well within his compass. Besides that, Cesare had everything to gain from Juan’s death. Ever since 1488, Cesare had coveted the Duchy of Gandia and all the other honours and riches their father had conferred on Juan. Now, with Juan removed from the scene, he had his chance but was checked at first by his father’s protests. Alexander had taken a great deal of trouble to place Cesare in the College of Cardinals and was convinced that from this springboard, his son would one day become pope. But Cesare was too much a man of the world and in particular, a man of the sensual Renaissance world. He was more interested in hunting than in prayer, coveted wealth and women rather than spiritual integrity and preferred land and estates to a life of humility and sacrifice.

Juan’s young widow, Maria Enriquez de Luna and her family seemed certain that Cesare had murdered his brother.

Ultimately, Cesare got his way, if only because Jofre, the son Pope Alexander planned would take Juan’s place, proved too weak and diffident to face up to the challenges involved. Cesare, an inspiring military leader and a first-class strategist, was much more the vigorous strong man required to realize his father’s ambitions. This was why, however reluctantly, Alexander allowed Cesare to resign holy orders in 1498, the first cardinal ever to do so.

In 1503 the artist and polymath Leonardo da Vinci received this commission, with seal, from Cesare Borgia to take charge of building fortifications in the Romagna region.

Now, Cesare’s secular aims were within his reach. He was created Captain-General of the Church in his brother’s stead and in 1499, acquired a wife – the 16-year-old Charlotte d’Albray, who was the ideal daughter-in-law for a pope who aspired to all-embracing political power. Charlotte, the sister of King John III of Navarre, belonged to an aristocratic Gascon family related to the royal family of France and according to Italian envoys at the French court, was ‘unbelievably beautiful’.

But the two-month honeymoon Cesare and his unbelievably beautiful young wife spent at a castle in his duchy of Valentinois created for him in 1498 by Pope Alexander, was the only time the newlyweds spent together. After July 1499, when he left the castle for the wars, Cesare never saw Charlotte again, nor their daughter, Luisa, who was born in the spring of 1500. Cesare fought first in support of his ally King Louis XII of France in the siege and capture of Milan and next at the head of the papal army against rebellious feudal lords in the Romagna, which lay adjacent to the Papal States in the northeast of Italy. Tribute to the pope was overdue and Alexander sent Cesare to teach the lords of the Romagna a lesson.

One story told of a supper hosted by Cesare Borgia at the end of October 1501 where 50 courtesans danced naked with 50 servants.

Both campaigns were extremely successful and in Jubilee year, 1500, Cesare and his father provided Rome with the greatest bonanza celebration the Borgias had ever staged. It featured, for a start, a bloody spectacle reminiscent of the gladiatorial games of ancient Rome, in which Cesare, resplendent on horseback, cut off the heads of six bulls in St Peter’s Square to wild applause from the watching crowd. According to rumours and stories circulating in Rome, and supported by the diaries of Johann Burchard, the celebrations continued with a session of debauchery that exceeded virtually all other acts of depravity the Borgias had so far committed.

One story told of a supper hosted by Cesare Borgia at the end of October 1501 where 50 courtesans danced naked with 50 servants. This was followed by an orgy in which whoever made love to the prostitutes the most times or produced the ‘best performances’ received prizes. The onlookers, who included Pope Alexander, Cesare and Lucrezia, selected the winners. Foreign diplomats in Rome, who regularly transmitted salacious gossip about the Borgias to their masters at home spread the news that the papal apartments had been turned into a private brothel where at least 25 women came into the Vatican each night to provide the ‘entertainment’ at parties attended by Pope Alexander, Cesare and large numbers of cardinals. Pope Alexander had increased membership of the Cardinals’ College by nine new candidates, each having paid thousands of ducats for the privilege.

Lucrezia dances for her father, Pope Alexander VI, and his guests at one of his infamous parties.

The money went to line the pockets of the pope and Cesare who were already rich enough to make the fabled King Croesus of Lydia envious. Probably the most scurrilous purveyor of gossip about the Borgias was one of their greatest enemies, a certain Baron Silvio Savelli, whose lands had been confiscated by the pope. Savelli hated Alexander with savage intensity. After receiving an anonymous letter from Naples that overflowed with the most scandalous details about the pontiff and his family, Savelli had it translated into every European language and circulated it around the royal courts of Europe. The letter named Pope Alexander as ‘this monster’ and ‘this infamous beast’ and continued:

Who is not shocked to hear tales of the monstrous lascivity openly exhibited at the Vatican in defiance of God and all human decency? Who is not repelled by the debauchery, the incest, the obscenity of the children of the pope… the flocks of courtesans in the palace of St Peter? There is not a house of ill fame or a brothel that is not more respectable!

Although the case was overstated in order to defame the Borgias to the maximum, these accusations hit the target for many more of the family’s enemies in Rome. For years, cardinals, clerics and nobles had been crushed under the wheels of Pope Alexander’s ambition, his flagrant nepotism, his greed for lands and estates, the presence in the Vatican of his mistresses and bastard children, and the insults his debauched life had offered to the Church. But it was not until 1503, when he died at the papal palace in Rome, probably of malaria, that they were able, at last, to hit back. Cesare, too, contracted the disease that had been spread through the city by clouds of mosquitoes, but he was younger and healthier and survived.

Despite, or maybe because of, his physicians’ efforts, which included bleeding him regularly, Pope Alexander expired after almost a week, on 18 August. The news was kept secret for several days. Nevertheless, panic gripped members of the Borgia family still in the Vatican, for they knew, as Cesare did, that with the pope gone all guarantee of their safety had disappeared with him. Some of them fled Rome immediately. Others remained behind only long enough to loot Alexander’s treasury and ransack the papal apartments for gold, silver, jewels, gold and emerald cups, a gold statue of a cat with two large diamonds for eyes and the mantle of St Peter, which was covered in precious stones. The loot was hidden in the Castel Sant’Angelo and only then was the announcement made that the pope was dead. Death and the sweltering August weather had so distorted Alexander’s body that it became a thing of horror to look upon. Johann Burchard recorded:

A painting of the death of Pope Alexander VI by the German realist painter Wilhelm Trübner (1851–1917). Rumour had it the pope was poisoned, but it is more likely that he died of malaria.

Its face had changed to the colour of mulberry or the blackest cloth and it was covered in blue-black spots. The nose was swollen, the mouth distended where the tongue was doubled over and the lips seemed to fill everything.

Even when the grossly swollen corpse had been forced into its coffin, no one wanted to come near or touch it. A rumour had gone round that Pope Alexander had made a pact with the Devil in order to make himself pope in 1492, and that demons had been seen in the exact moment he had died. This may have been one of the reasons why priests at the church of St Peter refused to accept the pope’s body for burial. Others were disgusted at the condition of the corpse, or the disrepute the Borgia pontiff and his family had brought on the Catholic Church. Frightening threats were required to make the priests give in, and do their funerary duty.

For years, cardinals, clerics and nobles had been crushed under the wheels of Pope Alexander’s ambition, his flagrant nepotism, his greed for lands and estates, the … mistresses and bastard children, and the insults his debauched life had offered to the Church.

The black reputation of the Borgias also kept most prelates in the Vatican away from the Requiem Mass normally said for departed popes, and only four made an appearance. Francesco Piccolomini, who succeeded him as Pope Pius III, banned another Mass, for the repose of Alexander’s soul. ‘It is blasphemous,’ Pius proclaimed ‘to pray for the damned.’ Eventually, Alexander was buried in the Spanish national church of Santa Maria di Monserrato in Rome.

The Borgia ‘empire’, which had taken Alexander so many years and so much intrigue and effort to build, soon fell apart after his death. While her father lived, Lucrezia had enjoyed some importance as a link with the pope that was used by ambassadors, envoys and other hopefuls seeking papal favours. Alexander’s cousin, Adriana del Mila performed a similar function, for as one contemporary diarist wrote of the house in Rome the two women shared: ‘The majority of those wishing to curry favour with the pope pass through these doors.’ All that came to an abrupt end once Alexander died.

Cesare’s power vanished just as quickly. Old enemies – the Orsini, Guidobaldo da Montefeltre, Cesare’s sometime brother-in-law Giovanni Sforza, the feudal lords of the Romagna – all came back to reclaim the rights and territories he had taken from them. In 1503, Alexander’s greatest and most enduring enemy, Giuliani della Rovere became pope as Julius II and at once set about making it impossible for the Borgias to retain their hold over the Papal States. Captured and imprisoned by Gonsalvo di Cordova, another vengeful foe with ample reason to hate all Borgias, Cesare managed to escape and ended his life in 1507 as a humble mercenary fighting for his brother-in-law, King John III of Navarre. Cesare’s much misused sister, Lucrezia, died in 1519 from complications caused by her eighth pregnancy.

Panic gripped members of the Borgia family. Some of them fled Rome immediately.

With Lucrezia, the last major player of the infamous Borgia era was gone, but neither she, nor her father, nor her brother Cesare have ever been forgotten. The legend of Borgia nepotism, simony debauchery, murder and dirty dealings of almost every other kind lives on and their name has become a byword for infamy that persists to this day.

The bedroom of Lucrezia Borgia in the castle at Sermoneta, in which she lived from 1500–1503, has been preserved as a museum.