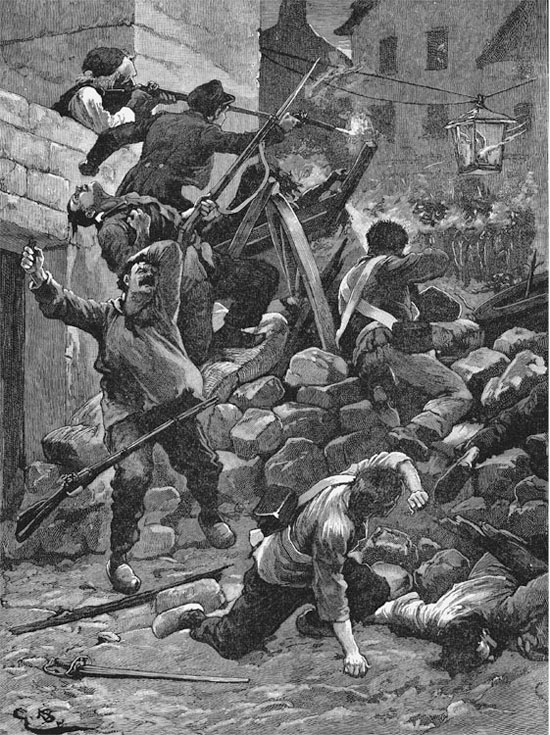

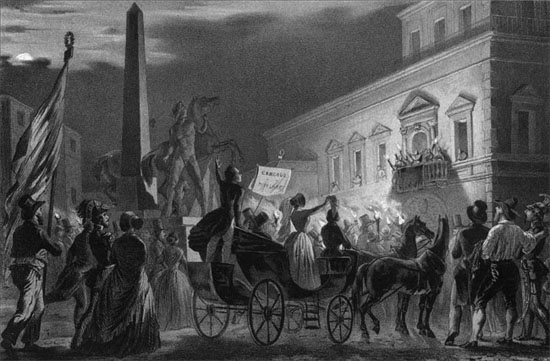

Paris was just one of the European cities which saw violent clashes during the Europe-wide uprisings of 1848, in which ordinary people claimed new rights and freedoms.

The year 1848 was the most terrifying ever experienced by the authoritarian monarchs of Europe. The pope in Rome, who exercised similarly absolute rule over the Papal States in central Italy, was not immune and was, in fact, affected even more fundamentally than his fellow despots.

![]()

Even Pope Pius IX suffered the consequences, changing his views from liberal to autocratic almost overnight.

For the first time ever, their power and the total control they exerted over their subjects was under serious threat. The threat originated from the rise of new, liberal ideas as expressed in the slogan of the French Revolution, which had convulsed the continent some 60 years before: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. These novel concepts spread across Europe in subsequent years, giving hope of a freer life to downtrodden millions.

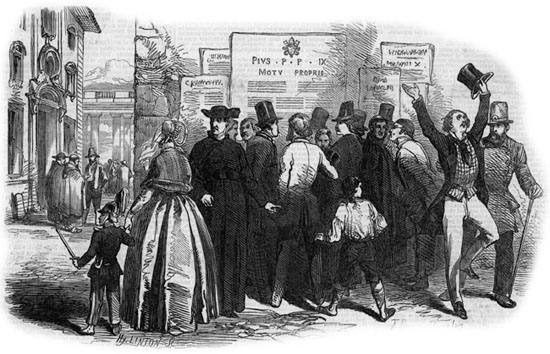

Pope Pius IX, who had been elected two years previously in 1846 seemed at first an unlikely casualty of this ‘revolutionary wave’, as some historians have labelled the events of 1848. His predecessor, the ultra-conservative Gregory XVI, believed that modernity in all its forms was innately evil. This applied especially to technological advances such as lighting the streets by gas or the new, faster form of travel introduced by railways, which Gregory viewed as works of the Devil and contrary to the way God meant life on Earth to be. Pius, who was nearly 30 years younger than his predecessor, welcomed progress and was one of the few European rulers with a liberal cast of mind. Among Pius’ innovations on becoming pope were gas street lighting and railways, the very advances Gregory had condemned. He also freed political prisoners from the papal jails and set out to reform the inefficient and corrupt bureaucracy of the Vatican. Plans were laid to curb the activities of the Inquisition, abolish the Index of Prohibited Books and to free newspapers and books from heavy censorship. New civil liberties and the introduction of democracy were on the cards. But Pope Pius never implemented them and just how much further the liberal pope would have gone in modernizing the papacy was never revealed. By January 1849, exactly a year after the revolutions, Pope Pius had abandoned his liberal ideas and become as reactionary and authoritarian as his fellow despots.

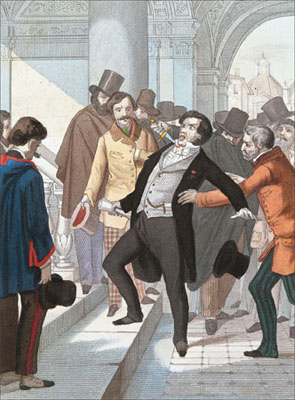

What had happened to bring about such a total U-turn? The short answer is that the revolutionary drive towards ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’ became so remorseless it promised to sweep away the ‘old order’ and do so with utmost violence and bloodshed. In the Papal States alone, popular disorder was so widespread it made the streets dangerous. Demands for a new constitution were so strident that Pius’ probable agenda – to introduce liberal change gradually and under his own direction – became utterly unworkable. A climax was reached when Pope Pius’ strongman Prime Minister, Pellegrino Rossi, was stabbed to death on Vatican Hill on 15 November 1848. The murder was witnessed by numerous passers-by but no one, it seems, did anything to prevent it. The killer was never apprehended.

Pius freed political prisoners from the papal jails and set out to reform the inefficient and corrupt bureaucracy of the Vatican.

The first Vatican Council, called by Pope Pius IX, took place in 1869–1870 and had two main purposes: to confirm papal infallibility and to reinforce his anti-modern policy.

The liberal reforms Pope Pius promoted soon after his election, such as civil rights and freedom from censorship, were greeted with joy, but did not last long.

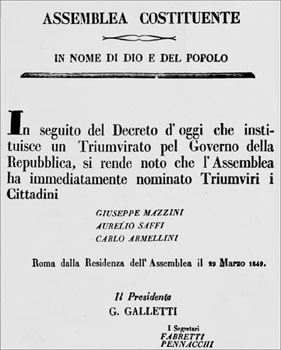

Rossi’s death left Pius severely shaken. Popes, after all, had been assassinated before, though not in the last nine centuries, but even so, Pius feared he could be next. To avoid this fearful fate, he resolved to escape from Rome and got away dressed as an ordinary priest, wearing sunglasses as a disguise. Fortunately, no one recognized the anonymous figure entering the Bavarian ambassador’s carriage and travelling south into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to Gaeta, a fortress on the coast north of Naples. Meanwhile, the Papal States were convulsed by revolts in Bologna and all points south as far as Rome. Throughout this area, the pope’s representatives, his legates, were driven out and replaced by local committees that lost no time proclaiming the end of papal rule. This was confirmed in January 1849 when an Assembly in Rome, which had been elected by popular vote, introduced a new Constitution in which the first Article stated that the temporal power of the papacy was abolished. From now on, the Constitution also proclaimed, the government of the Papal States would be democratically elected.

The murder of the Pope’s Prime Minister Pellegrino Rossi in 1848 made Pius IX fear for his own life. He fled to a hideaway near Naples.

Foreign intervention came to the aid of the pope, though, so rule by the liberal Assembly never got that far. Austria and France, both Catholic countries that had dominated Italy between them from 1713–1814, dispatched troops, sent the Assembly packing and restored Pius to the place and powers he had briefly lost. But it was something of a charade for the pope to have to rely entirely on his armed guards to maintain his presence. The Austrians, who occupied Lombardy northwest of the Papal States and Veneto in the northeast, now policed the pope’s territory. They, and the French troops who patrolled the streets of Rome, were all that stood between Pope Pius and further disaster.

Pius resolved to escape from Rome and got away dressed as an ordinary priest, wearing sunglasses as a disguise.

Pius was not made welcome when he returned to the Vatican, though his restoration created glad tidings for devout Catholics all over Europe. But the pope who came back to Rome was not the same pope who had left the city under such dangerous circumstances. Pius had been thoroughly disturbed by the vigorous and, in his opinion, impudent attempts to displace him from the role God had intended for all popes – the temporal rule over the Papal States and the spiritual rule of the Church. Pius IX felt that he had come far too close to losing both, and that made him all the more determined to re-impose the powers of the papacy but this time in autocratic form.

A printed announcement proclaims that a triumvirate has been chosen by the democratically elected Assembly to govern the short-lived Italian Republic in March 1849.

Meanwhile, other despotic rulers in Europe had also been knocked sideways by the intensity of the 1848 risings. However, by 1849 they had managed to restore their positions by dint of draconian suppression. Liberals were arrested, tortured and killed, and their followers were cowed and threatened into submission. The liberal constitutions the despots had been forced to grant, if only to play for time, were summarily withdrawn and absolute rule was re-introduced. Even so, life was never quite the same again for Europe’s autocrats. Their sense of security had evaporated and they felt bound to suffocate themselves in security. Life was never the same again for Pope Pius either, but for different reasons. Although the short-lived Assembly in Rome was defunct, the liberal constitution its members had passed into law remained intact. The pope had no power to withdraw it, as other despots had withdrawn theirs, and it remained the only new constitution to survive the brute-force retribution that destroyed the uprisings of 1848. And unlike other parts of Europe where the revolutions had failed, the Papal States and the rest of Italy had the means, the will and the people to make liberal dreams into reality.

The year of revolutions 1848 was a dangerous time for Pope Pius IX, as demonstrations against his rule took place in Rome.

The focus of liberal hopes was also, of course, a nemesis for Pope Pius IX. It was the Kingdom of Sardinia, which, despite its name was centred on Piedmont in northwest Italy where Turin was its capital. The Kingdom included the nearby region of Liguria as well as Sardinia, the second-largest island in the Mediterranean after Sicily. Under its sovereign, King Vittorio Emanuele II of the House of Savoy, Piedmont–Sardinia had used its constitution to turn what had once been an authoritarian state into a parliamentary democracy. The Church no longer controlled the schools, there was freedom of religion and the Jesuits, who were thought to be in league with the pope to the detriment of the kingdom, were thrown out. All this boded very ill indeed for Pius IX, who watched developments in Piedmont–Sardinia with great apprehension. Even worse, as far as the pope was concerned, Vittorio Emanuele was popular among his subjects through his support and encouragement of liberal reforms and they, in their turn, had turned away from the Church and, in particular from Rome, as the focus of power.

In a traditional papal pose, Pope Pius IX raises his fingers to give a blessing. With a reign of almost 32 years, Pius was the longest-lasting pope in history.

The Church no longer controlled the schools, there was freedom of religion and the Jesuits were thrown out.

As if this were not sufficient disadvantage for the beleaguered pope, Vittorio Emanuele was also that invaluable figurehead, a great patriotic war hero, having personally fought in four battles of the first Italian War of Independence against Austria in 1848–49. The purpose of the war had been to put an end to Austrian and other foreign control of Italy.

What it actually proved was that no single Italian state could defeat the foreigners on its own. Even though Piedmont–Sardinia lost the war, the youthful 29-year-old Vittorio Emanuele emerged as an inspiring leader and symbol of the Risorgimento, the movement for the unification of Italy.

In 1861, Vittorio Emanuele II of Piedmont-Sardinia became the first of the three kings of Italy.

As the warrior king rose in eminence and popular regard, the peril he posed to Pope Pius increased. Before long, the dream of transforming Italy from a collection of small separate states into a single monarchy, first mooted more than 30 years earlier, began to take more concrete shape, and nowhere more potently than in the ambitious mind of Vittorio Emanuele. Evidently, there would be little space for a pope, much less an autocratic one, in this scheme of things.

Vittorio Emanuele’s first chance to make his bid for rule over all Italy did not arrive until 1859, when another war with Austria broke out. This time, the King acted in partnership with the French, who wanted the Austrians, their great enemy, out of Italy. The decisive action of this new war came when Vittorio Emanuele triumphed against the papal army at the battle of Castelfidardo in the Papal States. Afterwards, the King drove the papal forces all the way southwest to Rome, some 200 kilometres away. The outbreak of hostilities was accompanied by revolts in the Papal States and once again the papal legates were driven out.

Evidently, there would be little space for a pope, much less an autocratic one, in this scheme of things.

With that, nationalists in Naples and Sicily began clamouring to unite with Piedmont–Sardinia and by 18 February 1861, the unified Kingdom of Italy was officially inaugurated. At that early stage, though, the whole of Italy had yet to be involved for there were two large areas still outside the new domain. One was in the northeast, where Veneto and its capital Venice were still controlled by Austria. The other, more significantly, was Rome and the Papal States, where the pope was fully geared up to fight all or any intrusion onto his sacred patch.

To this end, Pius deployed a weapon only he possessed. In a Papal Encyclical issued in January 1860, he excommunicated Vittorio Emanuele and everyone else who had been involved in the desecration of papal territory. Pius went on to inform the offenders that God was on his side, not theirs, and would undoubtedly act against them to reverse the outrage that had been dealt to His Church and to himself as His representative on Earth. It would therefore be wise, Pope Pius warned, if there were a ‘pure and simple restitution’ of the Papal States to their rightful owner.

Centuries earlier, in medieval times, excommunication and threats of God’s punishment had been quite enough to terrify all but the most recalcitrant into instant obedience. But this effect had long been fading in Italy, where many people, particularly among the educated classes, had become alienated from Rome, if not yet from the Roman Church and no longer trembled at the very thought of God’s vengeance. In this context, Pius was out of his political depth. He was not addressing impressionable devotees, but worldly men with little regard for shielding their immortal souls against penalties from Heaven. They were more concerned with political advantage and how to seize it for themselves.

Pius went on to inform the offenders that God was on his side, not theirs, and would undoubtedly act against them.

Several private agendas were in play. Vittorio Emanuele and his government set aside the capture of Rome for the moment while they concentrated first on ejecting the Austrians from Veneto. Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, two of the three nationalist leaders who spearheaded unification (the third was Camillo Benso, Conte di Cavour, Vittorio Emanuele’s erstwhile prime minister) held the opposite view. For them, the seizure of Rome was of primary importance because the Risorgimento could not be complete without Rome as the capital of Italy. The French emperor Napoleon III teamed up with Vittorio Emanuele for his own purposes – not only to eject the Austrians from Italy, but in the long term to ensure that instead of a unified Italy, there would be only a gaggle of weak states that could never rival France for influence in Europe.

A more important rivalry in the short term arose between Vittorio Emanuele and his government and the great military hero of the Risorgimento, Garibaldi, who attempted to upstage the King and seize Rome in 1860 and then in 1862. On both occasions, Garibaldi was thwarted but Vittorio Emanuele could not afford to leave it at that. Not only was Garibaldi a republican, he was a hugely popular figure among Italian nationalists. For them, Rome was the Holy Grail of the Risorgimento and Garibaldi’s ambition to capture the city was a great patriotic endeavour. Not only that, the continuing presence of French troops guarding the pope in Rome was a national disgrace that had to be erased.

The educated classes had become alienated from Rome, if not yet from the Roman Church, and no longer trembled at the very thought of God’s vengeance.

In these circumstances, Vittorio Emanuele’s ambitions to become King of all Italy were at stake. He could not afford to allow Garibaldi’s private, ragbag army to ‘liberate’ Rome and, as Vittorio suspected they would, declare a republic. He needed to take the initiative and remove the French himself. This, apparently, is what the King and his government aimed to do when they concluded the Convention of September with the French in 1864. Under this agreement, the French promised to evacuate Rome by 1866, unknowingly leaving Vittorio Emanuele free to implement his own clandestine plan – to manufacture some excuse to annex the city to his Kingdom of Italy and make it a royal rather than a republican capital. As a smokescreen for this aim, the King made what looked like major concessions: his government would transfer his capital from Turin in Piedmont–Sardinia to Florence in Tuscany, well away from Rome, and he would undertake not to attack the Papal States again.

On 20 May 1859, at Montebello in Lombardy, the forces of France and Piedmont thrashed the Austrians in what would come to be known as the Second War of Italian Independence.

Though a republican, Giuseppe Garibaldi hails Vittorio Emanuele II as King of Italy at a historic meeting at Teano, between Rome and Naples, on 26 October 1860.

On the face of it, these new arrangements afforded Pope Pius some welcome reassurance and filled him with a new sense of security. The pope’s optimism spread to his cardinals, who were just as convinced as their pontiff that Emperor Napoleon III would never depart Rome and leave Pius ‘in a helpless condition to the Piedmontese and the tender mercies of his subjects. The Catholics of France and of the whole world,’ the Cardinals maintained, ‘would not stand (for) it.’

Vittorio Emanuele’s ambitions to become King of all Italy were at stake. He could not afford to allow Garibaldi’s private, ragbag army to ‘liberate’ Rome and declare a republic.

The new mood of confidence in the Vatican was encouraged by events outside Italy that were moving towards a war in which Prussia was squaring up to Austria and both were in opposition to France. However, these three powers were linked by the belief that a united Italy could prove a rival to each and all of them when it came to exerting influence in Europe. It followed that all three meant to do their utmost to prevent Italian unification. This, inevitably, was greeted as great news in the Vatican, which had by far the most to fear from the Risorgimento. Nothing would have made the pope and his cardinals happier than the promise that the nascent Italian state was going to be put in its proper, backwater, place.

In January 1865, Odo Russell, the British envoy in Rome, reported home to London a conversation between himself and Cardinal Giacomo Antonelli, the pope’s formidable Secretary of State. ‘Like the pope,’ Russell wrote, ‘Antonelli hopes for a European war to set matters right again in the Holy See!’

But like other hopes engendered by the Convention of September, this turned out to be so much pie in the sky. The war between Austria and Prussia, which began in June 1866, failed to go the way the Vatican hoped. The pope had been certain that Austria would crush the Prussians, who had allied themselves to the Kingdom of Italy, and that the Austrians would soon occupy his own lost provinces.

… these new arrangements afforded Pope Pius some welcome reassurance and filled him with a new sense of security.

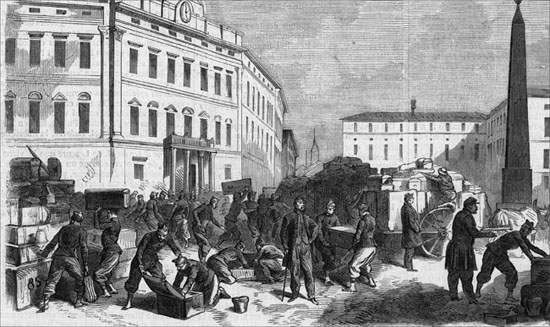

But the opposite was the case. The Prussians and their Italian allies triumphed, and quickly, for the war ended by October after only four months. The timing could not have been more inauspicious. By December 1866, under the Convention of September, the French were making preparations to leave Rome. Before the year was out, their flag had been taken down from its mast at the Castel Sant’Angelo and the French troops embarked at Civitavecchia, the port of Rome, bound for home. In the Vatican, all the earnest hopes, the optimism and the certainty that the French would never leave sailed away with them.

There were several subversive groups in the city who, given half a chance, would be only too willing to manufacture a rebellion.

With this, a sense of abject terror began to pervade the Vatican. Pope Pius’ advisors pleaded with him to get away to safety while he could, and seek sanctuary in Spain or Austria. Their fear was increased even further by the fact that Pope Pius and his autocratic rule had roused strong resistance within Rome. Even worse, there were several subversive groups in the city who, given half a chance, would be only too willing to manufacture a rebellion, with all the mob fury and destruction that implied. Undoubtedly, his aides were convinced, the pope was in deadly danger, but the prime source of that danger was not as they envisioned it.

The source was not malcontents and mobs, but the Italian government of King Vittorio Emanuele. The retreat of the French from Rome had painted them into an awkward corner. By signing the Convention of September in 1864 they had guaranteed papal rule in Rome, together with the security of the Papal States, which they had promised not to attack. For the sake of his honour and future credibility as monarch of all Italy, Vittorio Emanuele could not afford to renege openly on these commitments. What he could do, though, was to renege behind the scenes.

The pope had been certain that Austria would crush the Prussians, … But the opposite was the case.

For quite a while, Emanuele’s government had been secretly financing the subversive, anti-papacy groups active in Rome in the hope that they would foment a ‘spontaneous’ uprising. Giuseppe Garibaldi, a virulent anti-papist, stoked up the temperature by calling the papacy ‘the most noxious of all sects’ and demanding the removal of the Catholic priesthood, which he believed encouraged ignorance and superstition. Once the fires of rebellion were lit, Emanuele could play saviour and rush his own troops into Rome to retrieve the situation. Then, taking over the city and the Vatican and neutralizing the pope would be a piece of cake.

But it was not. Events turned out very differently. Despite all persuasions, generous handouts and Garibaldi’s revolutionary fervour, Rome stubbornly refused to rise. Partly this may have been due to the presence in the city of Pope Pius’ personal guard, most of them foreigners and many of them thugs. Another force, comprising papal irregulars, patrolled the city’s streets and had an even more fearsome reputation for violence. Emperor Napoleon III carefully watched these events, or rather non-events, from Paris. No mean intriguer himself, the crafty Napoleon easily recognized the signs of deceit and double-dealing and towards the end of 1867, he ordered French troops back into Rome where they were soon policing the streets once again.

Today, the revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi remains a great Italian hero for the military campaigns he fought in the cause of Italian independence.

Pope Pius, his cardinals and the rest of the Vatican were overcome with joy at what they saw as a timely rescue. The British envoy in Rome, Odo Russell, held a more sombre, realistic view. The presence of the French forces, he wrote ‘tends to make of Rome a fortified city and of the pope a military despot’. But there was no doubting the jubilant mood that had gripped Rome when the French returned. The pope’s supporters, the clerical party, Russell continued:

rejoice with great joy in their present turn of fortune and believe in their future triumph. [They] pray devoutly that a general European war may soon divide and break up Italy.

When Russell had an audience with the pope in the spring of 1868, the pontiff told him that, as a proportion of Rome’s population, the papal army was now the largest in the world and if the interests of the Church ever required it, ‘he would even buckle on a sword, mount a horse and take command of the army himself’. Pope Pius was 75 years old at the time.

A splendid scene of colourful pageantry as the papal procession passes through the streets of Rome at the inauguration of Pope Pius IX in 1846. Pius would see many changes in his long and eventful reign.

But for Pius, the interests of the Church required much more than bravado and military display. As a European ruler, he was unique in having a spiritual hold over millions of devout Catholics who were dispersed throughout the continent and prepared to obey his every pronouncement and follow his every lead. There were also other Catholics who had slipped into ‘error’ by embracing the modernity Pius had once supported himself. Such deviants needed to be drawn back into the fold. In 1864, Pius had already outlined the way he meant to do it, by forging a narrower path of permitted belief than any pope before him had ever devised.

Pius’ first targets were religious freedom and equal rights for all religions, which he rejected outright as ‘the greatest insult imaginable to the one true Catholic faith’. This equality, the pope told Emperor Franz Josef of Austria in a letter written in 1864 ‘contains an absurdity of confusing truth with error and light with darkness, thus encouraging the monstrous and horrid principle of religious relativism, which… inevitably leads to atheism’. These deeply reactionary and conservative ideas found their way into the papal encyclical called Quanta Cura (Condemning Current Errors), which was proclaimed by Pope Pius on 8 December 1864.

Quanta Cura created a furore of protest across Catholic Europe, but Pope Pius seemed entirely unaware of it. Instead, he staged a grand jubilee in Rome to affirm his iron resolve to steer the Church away from insidious modernity. Early in March 1866, vast, colourful processions wound their way through the streets of Rome. Taking part were cardinals in brilliant red robes followed by a throng of monks and friars bearing sacred images and a blaze of candles to light the awe-inspiring scene. At several of Rome’s most historic churches, the processions halted while priests piled up books banned by the papal Index and set them on fire.

Pius’ first targets were religious freedom and equal rights for all religions, which he rejected outright as ‘the greatest insult imaginable to the one true Catholic faith’.

But Pius kept the best, or as his enemies saw it, the worst, revelation till last. The First Vatican Council, attended by a huge gathering of cardinals and bishops, opened at St Peter’s Basilica on 8 December 1869. The Council had two purposes: to ratify the Syllabus of Errors of 1864 and to endorse a new principle in Church doctrine, the infallibility of the pope. This applied when the pope spoke officially on the subjects of faith and morals after God had revealed them to him.

Even Quanta Cura and its Syllabus of Errors had not administered a shock as great as this, and both critics and supporters voiced strongly worded opinions on the subject. However, the opinion that really mattered was Napoleon III’s. Thus far, he had been willing to bolster the pope, if only as a concession to French Catholic sensibilities. But now, His Holiness was proposing to throw over every civic freedom that had been gained in the last 80 years since the French Revolution, and make himself the divine arbiter of Europe’s future. It was too much. Napoleon made it known that if papal infallibility were voted into being at the Vatican Council, he would withdraw French troops from Rome.

The ballot took place on 18 July 1870. The pro-infallibility lobby won by 547 votes to two against. However, Pope Pius did not have things entirely his own way. His powers of infallibility were not nearly as comprehensive as he had wanted. They had been watered down by the opposition, which managed to detach the basic principles of civil liberties from the condemnations set out in Quanta Cura and its Syllabus of Errors. It was, however, significant that the ambassadors of the principal Catholic countries in Europe – France, Austria, Spain and Portugal – were conspicuously absent when the vote took place.

His Holiness was proposing to throw over every civic freedom that had been gained in the last 80 years since the French Revolution.

French troops pack up, ready to depart from Rome in 1866, leaving the city without its former protection.

In this early photograph, Pope Pius IX blesses his troops before the battle of Mentana which took place on 3 November 1867. The papal forces, with the French, routed the volunteer army of Giuseppe Garibaldi, preventing them from capturing Rome.

Fate, however, had a curious twist in store for both the Emperor Napoleon and Pope Pius IX. On 27 July 1870, the French announced they were going to remove their troops from Rome because, it was said, they were ‘needed elsewhere’. This had nothing to do with Napoleon’s threat or with papal infallibility. ‘Elsewhere’ lay along the border between eastern France and Prussia, the largest and most powerful of the German states. Tensions had been growing for some time and, on 19 July, the day after the ballot in Rome, the French declared war.

The Franco-Prussian War, which lasted less than a year until it ended in decisive Prussian victory on 10 May 1871, was a complete disaster for France. The hostilities ruined Napoleon III, who was captured by the Prussians, and afterwards exiled in England. This brought an end to monarchy in France, and as a final insult to a defeated opponent, the Prussians declared the unification of the German states under their leadership in the spectacular Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, built by the French King Louis XIV some 150 years earlier.

… the French announced they were going to remove their troops from Rome because, it was said, they were ‘needed elsewhere’.

For Pope Pius, the war was a disaster of another kind: the defeat of his erstwhile French ally meant there was nothing to prevent Vittorio Emanuele and the Italian government seizing Rome and declaring the city the capital of united Italy. This gave rise to fearful rumours that the pope was about to desert Rome and leave its already panic-stricken inhabitants to their fate at the hands of the terrible nationalists. It was whispered that the Jesuits were urging Pius to get away at once, ask the British for protection and move to the British-ruled island of Malta. The only hope seemed to be for the pope to negotiate with Vittorio Emanuele and his government and prevent the occupation of Rome that way. Even the stalwart Cardinal Antonelli begged the pope to take this course, but no amount of pleading or panicking had any effect.

This was not just the reaction of a stubborn old man entombed in his own arrogant world. He had – or thought he had – much more than that on which to fall back. First of all, Pope Pius was relying on the promises he had received from Count Otto von Bismarck, the ‘Iron’ Chancellor of Prussia, the Prussian King Wilhelm I and the Italian government itself that there was no prospect that papal territory would be invaded. This was why Pius grew so angry when army officers and the papal police seemed unable to get the message. For example, when the papal commissioner of police came to him and asked for instructions about what to do when the invaders came, Pius, in spite of his age, leapt from his seat in a fury and shouted, ‘Can’t you understand? I have formal assurances that the Italians will not set foot in Rome! How many times must I keep repeating myself?’

The only hope seemed to be for the pope to negotiate with Vittorio Emanuele and his government and prevent the occupation of Rome that way.

What the pope did not seem to understand, though, was that in the everyday world outside the Vatican, assurances vanished when a change in circumstances warranted. This is what threatened to happen a month after the French left Rome. On 20 August 1870, in the House of Deputies (the Italian ‘parliament’), the government won a vote of confidence that came with a significant condition: the King’s ministers must find a way ‘to resolve the Roman question in a manner in keeping with national aspirations’.

Pope Pius IX announces papal infallibility on matters of faith or morals. This new ‘power’ polarized Catholic opinion, gratifying some, but horrifying others.

The message was coded, but it was easy to see what it inferred: if ‘national aspirations’ were to be fulfilled, the ‘Roman question’ could not be resolved in favour of the pope. The leader of the Catholic Church in England, Cardinal Henry Edward Manning, certainly read danger in this new situation and had an urgent meeting with the British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, to arrange aid and, if necessary, rescue, for the Holy Father. Soon afterwards the British warship HMS Defence sailed into Civitavecchia. It was under instruction to embark the pope if he wished to leave.

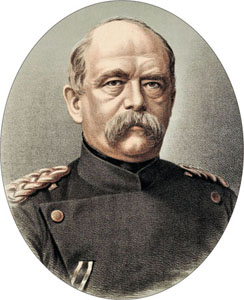

Count Otto von Bismarck, the so-called ‘Iron Chancellor’ of Prussia and great enemy of Napoleon III who fulfilled his ambition of unifying the states of Germany under Prussian leadership in 1871.

It was a shrewd precaution. Behind a façade of reassurances that there would be no assault on Rome, the Italian government was desperately searching for a pretext that would enable them to seize the city. Despite the fact that the idea had failed before, the Italians fell back on the ‘spontaneous’ unrest that could be caused inside Rome to give them a ‘duty’ to intervene. There could be heavily armed attacks on military barracks, hopefully leading to a popular uprising. The papal troops, who were chiefly foreigners, might be bribed into quarrelling with each other, creating brawls in the city streets that would soon be joined by the inhabitants.

Guns could be fired at night while Italian flags were raised here and there. This would give the impression, as Prime Minister Giovanni Lanza put it to a group of young conspirators, ‘that Rome was in the throes of anarchy and that the pope’s government could no longer control the situation with its own forces’. Lanza went on to sound a note of caution. ‘See that as many disorders as you like break out in Rome,’ he told the conspirators ‘but not revolution’.

This was a risky, impetuous policy and one that earned no approval from the cautious Minister of Foreign Affairs, Emilio Visconti-Venosta, who had hoped that a compromise could be reached between the pope and the Italian government. Chancing his arm was not part of Visconti’s nature and to the last, he hoped that somehow, ‘the pope’s independence, freedom and religious authority could be preserved’.

But the greatest obstacle to this ambition was Pope Pius himself. He had no intention of negotiating with the Italian government because this would give it recognition and legitimacy, something he would never allow. Even the reasonable, emollient Visconti was unable to penetrate papal resistance. Neither did a government plan, revealed in September 1870, to give the pope the so-called Leonine City, a section of Rome that included the Vatican and lay on the right bank of the River Tiber.

Predictably, Pope Pius dismissed the idea. As far as he was concerned the forces of God were struggling with the forces of the Devil for control of Rome, and the Devil, in the form of the government of King Vittorio Emanuele was going to lose. In less apocalyptic terms, perhaps, this was also the general opinion in the Vatican.

Emperor Napoleon III of France, whose troops policed Rome and protected the Vatican and the pope.

This, though, was before the capture of Napoleon III by the Prussians, the abolition of the monarchy in France and, finally, the resounding victory of Prussia in the war of 1870–71. Although he was stunned by these events, in particular the departure of Napoleon from the scene, Pope Pius persisted in turning down more last-minute proposals for settling the dispute without war. One of them, delivered on 10 September 1870 by a Piedmontese nobleman, Count Panza di San Martino, came from King Vittorio Emanuele, pledging that the independence and prestige of the Holy See would be protected.

The war of 1870–1871 between France and Prussia ruined Napoleon III, who was captured by Prussian forces in September 1870 and went into exile.

Pius read the King’s letter, but refused to answer it directly. Instead, he sent a short missive to the King. He wrote, ‘Count Panza di San Martino has given me a letter that Your Majesty wished to direct to me but one that is not worthy of an affectionate son who claims to profess the Catholic faith.’ To respond to the King’s proposals, Pius asserted, would be to

… renew the pain that my first reading caused me…. I bless God who has seen fit to allow Your Majesty to fill the last years of my life with such bitterness. I ask God to shed his grace on Your Majesty, protecting you from danger and dispensing his mercy on you who have such need of it.

Better, the pope was sure, to stand firm, tough it out, and … die rather than compromise and hand over the papal lands that rightfully belonged to God.

The underlying message was, of course, the same as before. There were to be no craven concessions to the Devil and his hordes. Better, the pope was sure, to stand firm, tough it out and, if necessary, die rather than compromise and hand over the papal lands that rightfully belonged to God. In the event, Pope Pius did not die in the defence of Rome. Instead, his stubborn stand made him what he himself described as the ‘prisoner of the Vatican’. He never left the enclave until his death in 1878 and over the following 50 years, neither did three of the four popes who came after him.

Giovanni Lanza was President of the Council of Ministers of Italy (equivalent to Prime Minister), between 1869 and 1873. He was instrumental in establishing a government of united Italy in Rome.