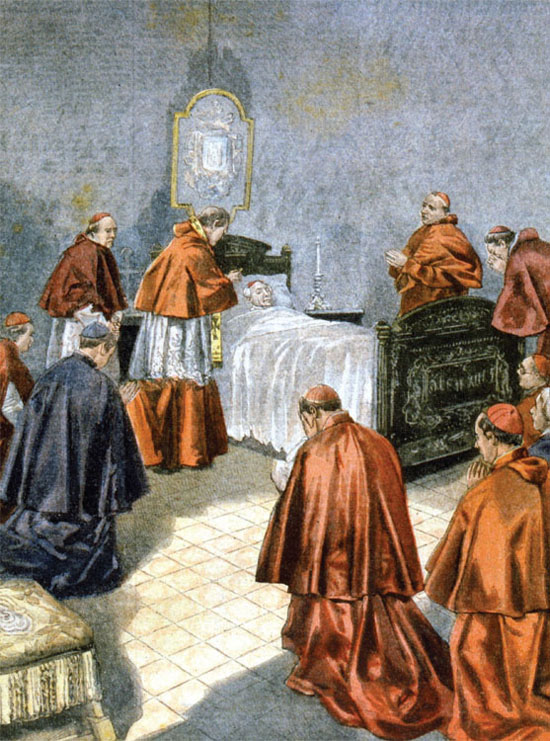

Cardinals pray (pictured) as Pope Leo XIII lies dying in 1903. Pope Leo was as convinced of his infallibility as his predecessor, Pius IX.

The Kingdom of Italy declared war on the Papal States on 10 September 1870. Two days later, Italian forces crossed into papal territory. Four days after that, they captured the port of Civitavecchia.

![]()

Pope Benedict XV (pictured) reigned as pope from 1914 until 1922.

From there, they advanced slowly towards Rome, some 60 kilometres (37 miles) distant, hoping that some compromise could be reached to save them from having to take the city by force. To this end, they plastered propaganda posters on walls with a message expressing goodwill and peaceful intentions.

Inside Rome, the Vatican authorities had no faith in propaganda. Instead, following the pope’s own lead, they remained certain that divine intervention would produce a last-minute rescue. It failed to materialize. By 19 September, the Italians had reached the Aurealian Walls, a structure 18 metres high and 19 kilometres long that surrounded Rome. Now, Rome truly was under siege. So too was Paris, which was ringed by the Prussians on the same day. It was clearly impossible for the Vatican to expect help from the French, but Pope Pius anticipated a move from Austria, the most powerful Catholic state in Europe.

The Austrians, however, were reluctant to take a pro-Vatican stand in case it led them into a war with the Italians, something the Austrian Emperor Franz Josef wanted to avoid at all costs. The best the Austrians could do was express their devotion to Pope Pius and offer him shelter in any city within the Austro-Hungarian Empire should he decide to leave Rome.

Monsignor Scapinelli, the apostolic nuncio in Vienna, exploded with rage when he received this message. ‘It takes some nerve,’ Scapinelli told the Austrian foreign minister Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust, ‘to invite me to move into your house while you do nothing to prevent me from being thrown out of my own!’

Vittorio Emanuele, meanwhile, tried diplomatic pleas to persuade the pope to change his mind and settle the ‘Roman question’ by agreement. He had no luck. Pius refused to yield to humanitarian arguments citing the loss of life the use of force would incur.

Instead, he turned the argument on its head and told the Italians and their king that they, not he, would be responsible for any fatalities and would have to take the burden of immense responsibility before God and before the tribunal of history.

Both sides had clearly reached the final impasse. After this, there was nothing left but for the Italian forces to prepare their entry into Rome and for the pope to make a public demonstration of faith in God. For this purpose, Pope Pius, now 78 years old, knelt down and on his knees climbed the 28 Holy Steps near the church of St John Lateran. On reaching the top, he prayed to God imploring Him to protect his people. Many people in the crowd watching were moved to tears.

The best the Austrians could do was offer him shelter in any city within the Austro-Hungarian Empire should he decide to leave Rome.

The attack by the Italian army began at five in the morning of 20 September 1870. Dr Maitland Armstrong, the American consul in Rome described what happened:

The old walls generally proved utterly useless against heavy artillery. In four or five hours, they were in some places completely swept away, a clear breach was made near the Porta Pia 50 feet [15 metres] wide and the Italian soldiers in overwhelming force flowed through it and literally filled the city, simultaneously, the Porta San Giovanni was carried by assault. A white flag was hoisted over from the dome of St Peter’s. After the cannonading ceased, the papal troops made but a feeble resistance and they, who a moment before, ruled Rome with a rod of iron were nearly all prisoners or had taken refuge in the Castle of St Angelo or St Peter’s Square.

The army of the Kingdom of Italy assaulted Rome and captured it in September 1870, The walls of Rome were peppered with bullet holes.

The struggle for Rome, such as it was, was not nearly as brutal as Dr Armstrong suggested. The papal forces were under orders to put up enough resistance to show their willingness to defend the Holy See and the Italians were under strict instructions to limit the damage they wrought, refrain from firing at non-combatants and to leave the Leonine City untouched. Even though Pius had rejected the offer of the City, the Italian government still intended it to serve as the pope’s own territory.

Another factor that may have dampened the proceedings was the prevailing mood in Rome. The pope had his devotees, who were terrified that he was going to leave the City and abandon them, but many other Romans appeared to regard the invading troops as liberators, freeing them from authoritarian papal rule. Even more alarmingly, there were popular demands that all monasteries and nunneries be removed from Rome and the monks and nuns thrown out.

A political cartoon showing Pope Pius IX, his powers gone after 1871, gloomily departing the scene as the triumphant King Vittorio Emanuele II receives the acclaim of the Roman crowd.

The observer who once called the basso popolo, (the lower-class Romans), ‘wild and bloody’ had not been exaggerating. If these people had been minded to rise up to join the Italians, the occupation of Rome would have been a great deal more gory and destructive than it was, so it was in the interests of both sides to accomplish the task quickly and cleanly. Once that was done, terms of surrender were soon organized and the whole of Rome, apart from the Leonine City, became the realm of Vittorio Emanuele II, the first King of Italy.

Terms of surrender were soon organized and the whole of Rome, apart from the Leonine City, became the realm of Vittorio Emanuele II, the first King of Italy.

Rome was now transformed. One of the city’s newspapers published on 23 September put it in jubilant terms while listing the many ways in which life was restricted by papal rule:

After 15 centuries of darkness of mourning, of misery and pain, Rome, once the queen of all the world, has again become the metropolis of a great State. Today, for us Romans, is day of indescribable joy. Today in Rome freedom of thought is no longer a crime and free speech can be heard within its walls without fear of the Inquisition, of burning at the stake, of the gallows. The light of civil liberty that, arising in France in 1789, has brightened all Europe now shines as well on the eternal city. For Rome, it is only today that the Middle Ages are over!

This celebration of modernity and the freedoms Pope Pius had tried so hard to suppress set his attitude even more firmly in stone than ever before. The Italians tried to cede the Leonine City to the pope. He refused. An offer of homage was suggested but was also turned down because it would involve the pope receiving a representative of the ‘usurper king’, Vittorio Emanuele and this he would not do.

The Italian foreign minister, Emilio Visconti-Venosta wanted reconciliation between his government and Pope Pius IX, but realized that the pontiff would never contemplate it.

Eventually, it dawned on those who hoped for reconciliation, such as Emilio Visconti-Venosta or Prime Minister Lanza, that Pius would never accept any proposal, suggestion or even hint from the Italian government. Each and every approach the Italian government made to the pope met the brick wall of resistance, creating apprehension in the Italian government and poisoning the atmosphere at the Vatican.

A pall of gloom prevailed, with cardinals afraid to walk out in the streets, or drive in the splendid carriages that identified them as servants of the pope. Priests could be seen slinking along, obviously afraid of being recognized and harassed by hostile roving gangs. Perhaps worst of all, shouts of ‘Death to the pope!’ could be heard from outside the walls of the Vatican. Freedom of the press allowed seditious and blasphemous books to be sold openly in Rome, which stoked even further the hatred for the papacy, which was growing more and more apparent throughout the new Italian kingdom.

According to the pope’s indefatigable Secretary of State, Cardinal Antonelli, the government’s repeated claims of respect for the pope, concern for his welfare and safety and their desire to find a compromise that would enable him to function freely were nothing but a cynical cover for some terrible abuses. Antonelli’s list comprised a fearful indictment, including, he wrote:

Cardinal Giacomo Antonelli was a major figure in the Vatican during the 1848 liberal revolution and stoutly defended Pope Pius IX’s conservative reaction to it.

…the complete stripping of the august Head of the Church of all his dominions, of all his income, the bombardment of the capital of Catholicism, the impieties that are being spread through the population by newspapers, the violent attacks against religion and the monastic orders, the profanation of the Catholic cult, which is being labelled superstition, the stripping of all public schools of every sacred image, which has been ordered by government authorities and already cried out, the removal of the name of Jesus from above the grand portal of the Roman College.

It was against this dangerous background that Cardinal Antonelli was busy trying to encourage papal nuncios in European capitals to rouse to action governments that were friendly to the pope. His efforts produced a few, though not nearly enough, positive returns. In Germany, for example, princes, noblemen and lawyers in several states signed a petition condemning the occupation of Rome and the destruction of the pope’s secular power in the Papal States. In Belgium and several other countries, Catholics were encouraged to hold protest meetings at which they declared the seizure of Rome a sacrilege and the threats to the pope as virtual patricide. Protest processions were held and hundreds of masses were sung. Individual bishops in Germany and Belgium bombarded Vittorio Emanuele and his government with their personal protests. Much was made of the pope’s new appellation, the ‘prisoner of the Vatican’ and a great deal of hot air was expended on angry denunciation of the ‘heretic’ Italians and the punishments that awaited them for their ‘crimes’.

In Germany, for example, princes, noblemen and lawyers in several states signed a petition condemning the occupation of Rome.

But what Antonelli most fervently wanted – a concerted, Europe-wide campaign by Catholic governments, clergy and congregations that was vast and vocal enough to put real pressure on the Italians to withdraw from Rome and the Papal States and restore the pope to his rightful heritage – was not forthcoming. In his genuine desire to rescue Pope Pius from a desperate situation, Antonelli had overlooked a vital fact about late nineteenth-century Europe. The continent had moved on a long way from the days when rulers could stand on their autocratic rights and expect unquestioning obedience from their subjects. The revolutions of 1789 and 1848 had destroyed the Europe in which such attitudes prevailed. This was confirmed even more recently by an aftershock – the Paris Commune of early 1871 – in which workers, variously classed as anarchists or socialists, rose up against the French government, which had just been forced into accepting a humiliating peace by the Prussians.

The lukewarm response of the Austrians and Belgians to Antonelli’s pleas were indicative of this new situation, whereas Pius and his devoted Secretary of State were in denial about it. In reality, restoring an infallible pope who had publicly set his face against the modern world would create havoc. Newly enfranchised populations would be bound to rise in defence of their own hard-won civic rights and the freedoms that came with them. Besides, Pius was not interested in protests, demonstrations, reassurances or the wringing of hands. For him, the only acceptable outcome was that the Italian state should be dismantled. Vittorio Emanuele must be sent back to Piedmont, where he came from. Rome and the Papal States had to be retrieved and, as Antonelli himself put it, ‘the full and absolute restoration of the pope’s dominions and powers’ should be implemented.

In reality, restoring an infallible pope who had publicly set his face against the modern world would create havoc.

This amounted to a total impasse and it was still there in 1878 when both chief protagonists, King Vittorio Emanuele and Pope Pius, died. The King went first, on 9 January, aged 57, from pneumonia, after Pope Pius had acceded to his final request, which was to receive the Sacraments. The pope followed just over four weeks later, on 7 February. He was 85 years old and had served what is still the longest pontificate in papal history.

The Communards who fought for the socialist Paris Commune in 1871 are photographed around the base of the Vendôme column, erected by Napoleon Bonaparte to commemorate his victory at Austerlitz in 1805.

But while the Catholic world mourned, others took advantage of the pope’s demise to express their fury at his actions and attitudes. The Church and the Catholic clergy were persecuted in both Germany and Switzerland. In Austria, Pius was reviled for his refusal to receive a member of the imperial family who had come to Rome for the funeral of the late King. A secular, anti-Catholic party with a virulent hatred of the papacy now ruled France, the one-time protector of the Holy See. Spain and Belgium, though Catholic countries, were no friends of the Vatican, either.

The future of the papacy in relation to the Italian state did not look promising.

Against this background, the future of the papacy in relation to the Italian state did not look promising. What was needed was a pair of protagonists – king and pope – who were willing to work out a compromise. Above all, both needed to see the wisdom of moving off square one, which was where the deaths of Vittorio Emanuele and Pius IX had left them. Furthermore, both were backed by intransigent supporters so virulently opposed to their enemy’s cause that they reached for their strongest adjectives to heap appalling insults on each other.

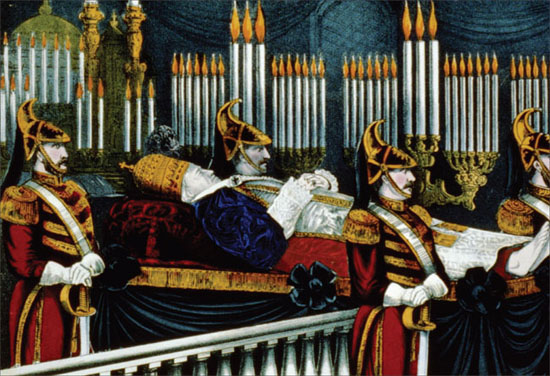

The funeral cortège of Pope Pius X who wears the triple crown of the popes as his body is taken in procession through the streets of Rome in 1914.

In this context, neither Leo XIII, who succeeded Pius IX as pope, nor Umberto I who became King of Italy on his father’s death, looked like working the miracle that was required to bring about a peaceful solution to the ‘Roman question’. Pope Leo was a cultured, gentle man. He was a diplomat and never indulged in the emotional fireworks favoured by his predecessor. He never spoke impetuously or acted without careful thought. Unlike Pius, Leo XIII understood the modern world and appreciated the benefits of democracy, though not all the way. He rejected equality and unconditional freedom of thought as unsuitable for ordinary people, who, he believed, were too immature and undisciplined to handle them properly.

Umberto I, the second King of Italy who was loathed by liberals and left wingers for his hardline conservative policies. Umberto was assassinated by an anarchist in 1900.

But the inescapable sticking point was Leo XIII’s belief in his infallibility as pope and with that, his inalienable right to retrieve and rule the whole of Rome and the Papal States. As always, the Kingdom of Italy stood immovably in the way of such ideas, as did its sovereign, Umberto I, who was firmly wedded to the principle that Rome was, and would remain, the capital of his kingdom. In any case, the times were too far out of joint for Umberto even to attempt an accord with the Pope. Throughout his reign, Italy was convulsed by the spread of socialist ideas and public hostility to various crackdowns on civil liberties. The upheavals this caused culminated in the assassination of King Umberto in 1900 by an anarchist, Gaetano Bresci, in Monza, in the north of Italy. Pope Leo XIII died three years later at the age of 93 years, still a prisoner of the Vatican. During the quarter-century his pontificate lasted, Leo never once set foot outside the precincts of the Holy See.

Leo XIII rejected equality and unconditional freedom of thought as unsuitable for ordinary people…

Reconciliation was even less likely between Pope Leo’s successor, Cardinal Giuseppe Sarto, who was elected as Pius X, and Vittorio Emanuele III, who became the third king of Italy on his father’s assassination. It had long been the custom for popes to choose the name of a predecessor they particularly admired and Pius X gave notice of his deeply conservative credentials when he chose the same name as the first ‘prisoner of the Vatican’, Pius IX. The tenth Pius proved to be a vociferous critic of ‘modernists’ and ‘relativists’ whom he classed as dangerous to the Catholic faith and its adherents. To emphasize these ideas, Pius X formulated an Oath against Modernism, which began in a truly uncompromising manner:

I firmly embrace and accept each and every definition that has been set forth and declared by the unerring teaching authority of the Church, especially those principal truths which are directly opposed to the errors of this day.

Those clerics who refused to take the Oath – there were about 40 who were courageous (or foolhardy) enough to do so – faced possible excommunication and so did scholars or theologians who strayed over into secular or modernist research during the course of their work. Although still ‘imprisoned’ in the Vatican, Pius X was not afraid to punish foreign heads of state who recognized the Kingdom of Italy and therefore, by inference, the Italians’ ‘theft’ of Rome and the Papal States. This stance could have embarrassing consequences, for when the President of France, Émile Loubet, made an official visit to King Vittorio Emanuele III, Pius X refused to receive him. The French retaliated by breaking off diplomatic relations with the Vatican.

The diminutive, timid Vittorio Emanuele III was not the man to deal with the righteous determination of Pius X, who towered over him both intellectually and physically. The tiny, delicate Cardinal Giacomo della Chiesa, a nobleman who was elected as Benedict XV on Pius’ death in 1914, was much more the king’s stature. Even the smallest of the three cassocks made for a new pope was still far too large for him. In consequence, he was nicknamed Il Piccolino (the little man) but there was nothing diminutive about his personal convictions.

Benedict strongly reiterated Pius X’s stand against the Italian ‘occupation’ of Rome and the Papal States.

Vittorio Emanuele III, the third king of Italy, was a tiny man of shy disposition who, unlike Pope Pius X, approved of liberal policies. But he never sought to promote his ideas in the face of Pius’ deeply conservative stance.

He also opposed modernism and those modernist scholars who had been excommunicated by his predecessor. The most dominant event of Benedict’s pontificate was World War I. He referred to this as ‘the suicide of Europe’ and tried desperately, but unsuccessfully, to halt it. But an even greater preoccupation and one that had a direct bearing on the safety, even the continuation, of the papacy emerged after the war came to an end in 1918.

Benito Mussolini’s followers barricade the Fascist Party building in Milan in 1922, the year Mussolini seized power in Italy.

The Russian Revolution of 1917, the slaughter of the Romanov royal family the following year, and the professed aim of the new Bolshevik rulers to spread their communist creed across Europe struck fear and apprehension right across the continent. The danger seemed especially acute to the Vatican, for the communist government was atheist and would soon set about dismantling the Orthodox Church in Russia. The spectre of godlessness being spread across Europe in the wake of a communist victory was too fearful to contemplate. Yet, contemplating it was necessary. In Rome, the danger assumed proportions far greater than those behind the struggle with the Kingdom of Italy or the occupation of the Papal States. Already, in 1919, a terrifying future seemed to be unfolding in Italy, where socialist activists were fighting right-wing fascists in street battles of the most violent intensity and taking Italy to the brink of anarchy.

For all his innate conservatism, Benedict XV was able to read the writing on the wall and his insights produced the first chink in the armour of papal resistance to the Italian state. In 1919, Benedict took a step that would have been anathema to his immediate predecessors: he sanctioned the setting up of the Catholic Popular Party, led by a priest, Luigi Sturzo. Previously, popes had barred Catholics from even voting in elections and certainly from holding elected office. Now, they were officially fighting elections and, in fact, did well on their first outing, coming second to the Italian Socialist party, with 21 per cent of the vote to the Socialists’ 32 per cent. Better still, to Pope Benedict’s considerable relief, the Popular Party, in coalition with the liberal government, shut the socialists out of power. But a much more fundamental upheaval was already on its way. Industrial strikes – 2000 of them in 1920 alone – together with unrest and violence from both the right and left of the political spectrum continued unabated until civil war in Italy seemed inevitable.

At this juncture, an unexpected saviour arrived on the scene. The Fascist movement formed in 1919 and led by a one-time socialist, Benito Mussolini, began to deploy gangs of thugs in the streets of towns and cities with the aim, quite literally, of battering their socialist and other rivals to defeat. The police, the military, the liberal right wing, wealthy businessmen and anyone else with a vested interest in peace for the sake of profit quietly approved, or at least turned a blind eye to the Fascist violence.

Mussolini pays his respects to King Vittorio Emanuele III after the fascist leader’s March on Rome in 1922 brought him to power in Italy.

Pope Benedict, who died early on in 1922, did not live to see the final outcome of these events. In October of that year, Mussolini made his ‘March on Rome’ where a thoroughly cowed King Vittorio Emanuele III, appointed him Prime Minister. Mussolini soon expanded his powers, abolishing all other political parties, the trade unions and all democratic freedoms. He replaced them with a totalitarian state with himself in charge as Il Duce (the leader).

Meanwhile, in the Vatican, a new pope had been elected to succeed Benedict and though he did not approve of the terrorist tactics Mussolini used to gain and keep hold of power, he saw in him a man with whom he could do business. Cardinal Achille Ratti, Archbishop of Milan, was a man of strong will and fervent belief. He was elected Pope Pius XI on 6 February 1922, in the last of 14 ballots. His first act as pope – restoring the blessing Urbi et Orbi (to the City and the World) – gave notice of a more international outlook than previous popes who had refused to make the blessing after the loss of Rome and the Papal States as part of their protest against the intrusions of the secular outside world on holy Vatican soil.

Mussolini watches as Cardinal Gaspari signs the Lateran Treaty of 1929. This momentous event brought nearly 60 years of papal isolation to an end.

Above all, Pope Pius XI was aware that in the twentieth century the world was driven by new imperatives now that four Empires and their absolute rulers in Germany, Russia, Austro-Hungary and Ottoman Turkey had been dethroned following World War I. In this context, old rivalries grew outdated and needed to be cast aside if new challenges – communists versus democrats, religion versus secularism – were to be effectively met. In accordance with this new reality, Pius XI accepted that the Kingdom of Italy was not going to go away, and that the Papal States had gone forever. From this, it followed that papal isolation had to end so that the Church could resume its missionary work and once more exert a global influence.

Benito Mussolini, for his part, cared little for the Catholic faith, the pope or anything else that did not bolster his own power. But he was an opportunist who knew perfectly well that his dictatorship labelled Italy as a rogue state and cast him as an enemy of democratic liberties. For these reasons, Mussolini welcomed the headline-making value of reconciliation with the pope and the esteem it would lend his regime, particularly among the millions of Catholics across the world.

On 25 July 1929, Pope Pius XI celebrated mass. Afterwards, he led a procession through the doors of St Peter’s Basilica and out into the midsummer sunshine that blazed down on the public square beyond, where a crowd of around one-quarter million was waiting to receive his blessing. The fifth and final prisoner of the Vatican had at long last been released from his self-imposed confinement and, for the first time in nearly 60 years, rejoined the outside world.

A smiling Pope Pius XI leaves the Vatican to make a splendid re-entry into Rome after the signing of the Lateran Treaty.