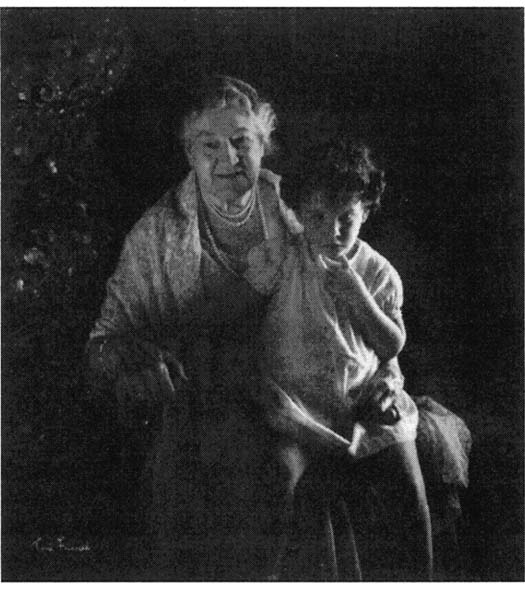

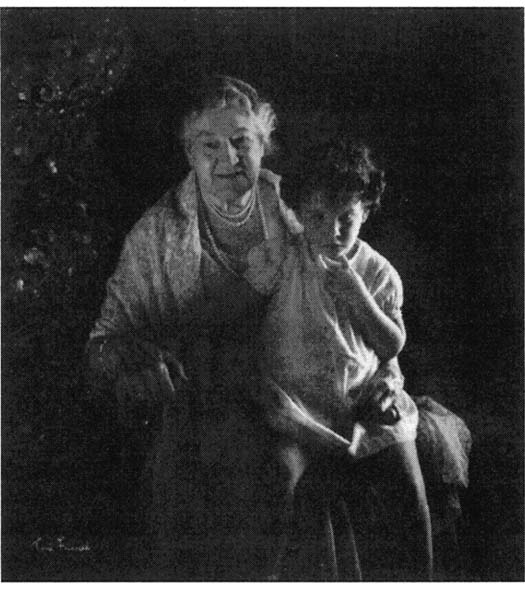

Bessie Smith White, my great-grandmother, was a handsome, big-boned woman, with thick white hair, parted on the side and drawn back loosely into a bun, so that it crested handsomely over her forehead. Her jaw was strong, and there was an aspect to her expression that was both imperious and elfin, albeit much softened by age. Time had also burnished and articulated her large, capable hands to a point of radiance. From the time I was two and a half I went to visit her every day. Sometimes she wore satin and pearls, and sometimes she wore raggedy things; often her dresses were of other decades; three-quarter length or long. The White Cottage, where she lived, had a porch on two sides where we would often sit in warm weather and have ginger ale and gingersnaps. As she got older, she would sometimes be in bed upstairs when I visited and on those occasions she would invite me to go down to the kitchen to get my ginger ale and gingersnaps myself.

In the middle of Grandma White’s lawn there was an ancient apple tree. It was so old that it bore only runty apples, but Grandma was interested in those miserable little apples, simply because they had appeared. She also loved Queen Anne’s lace, which seemed to me too plain for up-close attention—unlike, say, acorns or shells which she also liked. In winter she wore a black felt hat that fitted her perfectly—a lady’s hat, a hat that goes with the word “milliner”; and she had a red one exactly like it which she wore for fancier occasions. Her wool coat stretched flat across her back like a man’s. Sometimes she sent me out to pick dandelions for her, which she’d put in a glass with some water; but they’d wilt soon, though she didn’t mind. A statue of a boy taking a splinter out of his foot stood at the eastern end of her lawn—the end near the Red Cottage; wild violets grew all around it and when they were in bloom I picked them too.

Our hearts touched across an abyss of time—an abyss that was structured in that I was a very little girl in relation to a very old woman, in an almost archetypal way. Our relationship was reliable and without ambiguity of any kind, the fact that in her sheltering lap I was enveloped in an avoided history notwithstanding. There we are taking a walk in the woods, her large hand holding mine. We are wearing coats. The path is broad and covered with brown leaves. The leafless trees hold the light as if it were amber: there I am with Grandma in an amber of time where nothing moves on the emotional plane.

Stanford remained a living part of our history through the large presence on the Place of Grandma. Stanford was murdered in 1906, and I was born in 1944, but Grandma White lived on until 1950; we overlapped for six years. I can feel even now that my great-grandmother loved me.

It is, perhaps, indicative of how deeply that history was muffled in silence that Grandma, who embodied the history, was oddly without narrative in our family life. If she had had a “story”—even a girlhood story—it would have led too easily to the story of Stanford, in an unravelling way. The relationship between Stanford and Grandma was the primary one that defined and enclosed us as an extended family. Yet nowhere in the family picture of Grandma White that I received, or in my direct association with her, was there an intimation of disaster in her life and especially not in the areas of love and family. Grandma was, above all, placid. Certainly there was nothing in her demeanor that suggested an experience of murder in her family life.

The story about Grandma that had currency in the family was an ahistorical one: of her rootedness in the locality, of how she was sustained—and perhaps consoled, if the need for consolation can be floated free of a cause—by networks of kin and the small pleasures of the countryside with which she was so deeply familiar. She had dowager grandeur, but the story of Grandma in the family was the story of the thatch meadows and the clam flats, the berries and the beach.

Inside, Grandma’s house was sad. The wallpaper had lost its life. There were sparks of merriment in Grandma and a groundswell of affection, but there was also an atmosphere about her of huge passivity, of stubborn innocence, of surviving to great old age in a historyless way. She was there on the Place like an oak, like a rock, like a very large girl. She and I created a tie from farthest reach to farthest reach of the family as it existed then, and there was a special cozy tone in which our relationship was mentioned in the family—a tone that after I had grown up almost excluded me: “You don’t remember, do you,” my mother or my aunts were likely to say of the closeness between me and Grandma, and, when I said that I did remember, they didn’t notice, as if they were possessive of the memory, as if I had been a different person then and the memory belonged more to them than to me. Indeed, it is not easy for me to extricate my experience with Grandma from what our relationship means to others—to sense what it was, specifically and independently, for me to be engulfed lovingly in an innocence of that stupendous endurance, in that passivity, in a sadness that showed only in the wallpaper and in a certain deadness in the interior of a house.

You could get to Box Hill from Grandma’s by crossing a subsidiary driveway to Box Hill just west of her house and proceeding up a long, undulating path: a secondary axis, hedged with privet that had grown so high that in many places it joined overhead, funnelling you through shade toward a round opening of sunlight. At the end you were in a slightly elevated spot, with some barns and my uncle Bobby’s house on the left. Ahead and a little to the right across the fields, Box Hill nestled in its trees and snuggled into the land just below a hilltop. The hill crested just to the right of Box Hill, and there were pine trees on the crest. From the end of the Privet Path you could see through the pines to a bronze statue of Diana.

From the top of the Privet Path one noticed clouds, the reddish grass of the fields, and the real lay of the land—the falling off behind Box Hill, the swooping topography of an orchard to the right of Diana—in contrast to the molded planes of the grounds around the house, the long, evenly graded drive. This was Grandma’s landscape, something firm underneath, where I did not lose my edges as I could in the landscape that Stanford had superimposed on it. I have an image of how, when I was with Grandma White, the countryside steadied out around her, extending solidly and seamlessly to the horizon. In that steadied landscape Box Hill and the gardens dissolve, and so do Diana and the pines, until I see only a bare hilltop with a robin, a mulberry tree, a dandelion puff to blow.

Past Diana, the seamless landscape of the clouds and the swooping lines of the orchard continued down steep, wooded hills to the harbor. When I was a girl I had no idea that the windmill standing a little way to the west along the shore had been designed by Stanford—I saw it more as a feature of the natural landscape than as architecture. Indeed, it was the axle of the countryside of my childhood. The landscape of the windmill, so to speak, continued westward from the harbor, through woods and meadows to the Nissequogue River, a marshy, estuarial body of water that moseyed inland about three miles away. This was a landscape of special meaning and feeling that was charismatic and circumscribed. Across the Nissequogue River, for example, you were definitely no longer in it.

One factor that defined the boundaries of this landscape of tenderness and depth was the presence of Grandma’s branch of the Smith clan, a very large and old farming family that had founded Smithtown and had lived there in large numbers ever since. After ten generations, Smith kin extended to so many removes that they blurred, like trees across fields on a hazy day. As a child I subliminally “knew” that this landscape was ancestral, because my mother kept up the habit of visiting Smith cousins—a way of staying connected to Grandma, perhaps. More and more, though, as I got older she would just invoke their names as we passed their houses, with the result that I came to associate people with features of the landscape, rather than the other way around. From the time I was a very small child, perhaps four or five, it seemed to me that people became the landscape, in a way. Cousins Mildred and Josephine Smith, two elderly spinsters, were the big trees in their front yard as much as they were themselves. Cousin Dorothy Smith, whom I don’t remember ever meeting, was a gable peeking over the crest of a Smith truck-farming field that in summer was streaked with the greens, purples, and aquamarines of vegetable crops that rolled to the road like an ocean.

In this atmosphere it didn’t matter as much as it usually does whether a person had died or not. Since people were embodied in the landscape, it was easy to forget that a person had actually gone, and sometimes it seemed that people who were still alive had died long ago, because they had passed so completely into the landscape that actually seeing them would have been a shock. It was an easy step further—almost a matter of course—for me as a child to experience the presence of people in the landscape who had died before I was born. In a sense, everybody in the community—dead or alive—was both there in the landscape and not there, and it was perhaps this mixture of presence and absence that made the landscape susceptible to suddenly slipping out of ordinary time so that, for a moment, you would have no idea what the date or the year was: for a moment it could be very long ago. Anything could do it: a coincidence of angles, the light on a field, an unexpected glimpse of the harbor through a scrim of oaks, and especially a shift in sound, like wind rising—or falling—or crickets or birds falling silent. In that slippage, it would seem that something was uncovered that was always present but only out of mind.

As a very little girl I didn’t associate this subtexted countryside explicitly with Grandma—Grandma was there herself next door—but somewhere along the line Grandma too became a part of the countryside: not in a specific spot, as with her relatives, but at large, like a pressure in the atmosphere or like a sound. Grandma was present in the countryside like the sound of rainfall or wind in the trees: Grandma, with her dumb-beast entrapment in the physical body, her righteousness, her complacency, her simple love of me.

The wind-in-the-trees ancestral atmosphere that I sensed as a child was real; to a large degree the unusual aspects of Grandma’s character can be attributed to the encompassing Smith milieu in which she was raised. She had a simplicity, combined with a sense of belonging that was so settled and assured that not even association with the meteoric, catastrophic trajectory of Stanford White could shake it.

The history of the Smiths on Long Island began in 1640 when a yeoman from Yorkshire called Richard Bull Smith received the patent to the land that became the Town of Smithtown, and that he was a mere yeoman—unlike other recipients of large land grants—is the key to the simplicity of the Smiths, who never became pretentious. That he left all his land to his nine children, who in turn left it to their children, thus locking up the township for three generations, is the key to the Smith sense of entitlement and settledness without the attachment to status that one would expect to go with it. By that third generation Smiths were occupying all class levels in the township, and this pattern held right down to Grandma’s time, when, without self-consciousness or strain, her cousin Stanley Smith served as her chauffeur. To the Smiths wealth, fortune, and fashion had an unusually weak valence. A typical story is of Caleb Smith, who would go to Gilded Age dinners at a mansion near his farm where a hundred guests would be attended by a hundred liveried footmen: the next morning, without embarrassment, he would hitch up his team and go around to the mansion kitchen to pick up the slops for his hogs—the slops from the very dinner he had attended the night before.

Grandma grew up with her parents and eight siblings in the village of Smithtown, about four miles away from the Place, in the house that we later called the Smithtown House in the family. When I was a girl my uncle Peter (my mother’s oldest brother) and aunt Jehanne were raising their eleven children there. By the nineteen-fifties, the village of Smithtown had grown up around the house into a good-sized town, and the road in front had turned into a highway, but the house itself, and the land attached to it, belonged to a rural world. Built in Colonial times, the house was of substantial size, with several barns and farm outbuildings behind it: cribs, stalls, a carriage barn, a smokehouse, and an icehouse in which chunks of ice cut from a pond on the property were deposited in winter. Above the kitchen there was a slave quarters. It was the kind of farm designed not for cash crops but to sustain a family.

Grandma’s father, Judge John Lawrence Smith, was the farmer and he had his law offices in the house too, in a small wing with a separate entrance. He was the county judge, and when he grew too old to travel to Riverhead, the county seat, he turned his office into Judge’s Chambers and held court right there. “Judge Smith’s office was the real judgement seat for the townspeople, a place to be feared and revered,” Grandma wrote in a memoir of her childhood. Indeed Judge Smith was the most important man in both the family and the township.

Grandma’s father had been educated at Yale and Princeton and, as a young man, had worked in New York as a lawyer. There he had met and married Sarah Clinch, a socialite from a prominent family that was intertwined with the Nicolls, the Van Cortlandts, and the Van Rensselaers, all families of high status in the social and political establishment of the region. The couple lived in New York at first and then, after a few years, moved to Smithtown. Of their children five daughters and two sons lived to adulthood. Grandma was the youngest.

The Judge was a Victorian colossus of a father who reigned over his children like a god. He pulled their teeth; he made them memorize long passages of the Bible; he cured them of defects, such as stuttering (Grandma’s failing); he taught them how to carve a turkey, smoke a ham, make sausage—to do whatever he did himself about the farm. He gave them swimming instructions by pushing them into water over their heads from a flatboat on the Nissequogue River and, when the minister was away, he preached to them in church on Sundays too. While still a girl, Grandma regularly drove her father in a carriage fifteen miles to the railroad station at Islip where he would get a train to Riverhead. One day, they were overtaken by a cloud of locusts which flew into Grandma’s face and got stuck in her hair and her clothes, but the Judge would not let her protect her face or brush them away: he made her keep the reins in both hands, made her concentrate, throughout the ordeal, on controlling the horses. “I worshipped my father,” Grandma wrote in her memoir (the italics are hers), “who, I know now, must have been a very remarkable man.”

John Lawrence replaced the plain wooden mantels in the Smithtown house with marble ones and had the windows in the parlor transformed into French doors. When his fashionable mother-in-law became widowed, and came to live with them, he added a wing in the Palladian style to the east side of the house to serve as her quarters. Along the way, he also had a sturdy cage built in the attic. The purpose of the cage was to incarcerate Grandma’s sister Ella when she wanted to marry Charles Nicoll Clinch, a young army officer and a cousin on both sides. As a modern educated man, the Judge knew that too much intermarriage wasn’t good. The cage was made of sturdy planks: it was of a kind that had been used earlier in the century to imprison recalcitrant slaves. The story is that Ella was locked in the cage for a month, during which she was fed on bread and water. The engagement was broken.

Like the house, Grandma was both fancy and plain. She went to the one-room village school—the path to it would flood, and sometimes in winter she would skate there—and though she was the daughter of Judge John Lawrence Smith she swept the school floor in her turn. In her memoir, she tells of a countrified way of life, and there is something countrified about the telling too, in that the time the dog’s tail got stuck to the ice and the death of a sister are recounted in exactly the same tone. Her mandate as the youngest, she wrote, was to make her aging parents merry, and that she did this by skipping about and singing. (Her principal talent, it has come down in the family, was that she could whistle and sing at the same time.) She also writes:

Pig killing time was the most exciting time of the year. The kitchen laundry and all the outhouses were given up to sausage making, and head cheese, and the pigs were brought out and killed right there in the yard and hung up for two days in the cold air. I adored the sausage machine and used to love to grind the sausage meat and see it filling the skins while Lizzie tied it at intervals making it into “links” which were hung up in the attic, with dried catnip and all kinds of herbs! The old attic still smells of them, and I often think I can hear the pigs squealing as their throats were cut.

Grandma’s socialite mother, Sarah Clinch Smith, fled to the city at pig-killing time.

A kind of daffy delirium about the virtues of Smithtown is a Smith characteristic. Even the Judge was susceptible: in his otherwise detached and mildly ironic “History of Smithtown” he raves about the superiority of the breezes of Smithtown and the trout in the Nissequogue River. Grandma had that passion for the location too: in her case it was focussed with a special intensity on Carman Hill, the spot where Diana eventually stood. In Grandma’s time Carman Hill was not, as I had always imagined, a bare crest: there was a huge barn there, “a landmark for mariners for miles around,” she wrote in a memoir. There was a farmhouse where Box Hill later stood—indeed, in a sense, Box Hill grew out of it—and the land that in my time had grown up into woods was clear right down to the harbor. The Judge John Lawrence Smith family liked to swim at a small beach at the bottom of the hill, and when they passed Carman Hill Farm on the way to the beach, Grandma would jump out of the cart and run to the high spot where the big barn was to look at the view—it was the view that she loved—before running down, a distance of more than half a mile, to join the family on the shore below. When Grandma married, Judge Smith told Stanford that if he wanted his wife to be happy he had better buy Carman Hill Farm.

A dimension to Grandma’s life about which I heard absolutely nothing as a child, but without which her marriage to Stanford makes no sense, is that she had a great-aunt on her mother’s side, who had inherited from her husband, department store magnate A. T. Stewart, a fortune second only to that of John Jacob Astor. Aunt Cornelia took an active interest in her grandnieces in Smithtown. As each neared womanhood, an invitation was issued to live with Aunt Cornelia in the white marble palace in New York that A. T. Stewart had built at Thirty-fourth Street and Fifth Avenue. She sent her nieces to finishing school and introduced them to society: this is when the satin-and-pearls side of Grandma evolved. It was, despite her fondness for pig-killing time, a strong part of her aura. Grandma was both rustic and fancy. She was also an heiress: Aunt Cornelia’s Smithtown nieces knew that, along with other nieces and nephews, they would be included amply in her will.

Thus when Stanford met Grandma she knew how to make sausage and how to drive a buggy through a cloud of locusts, but she had also been to finishing school and had been around in New York society and, furthermore, stood to inherit a nice sum of money. The two aspects of her life were not in conflict, exactly, but they were not a conventional blend either: they were like an unusual chord. I have a little watch of Grandma’s, a Tiffany pocket watch, gold, with a cover on which her initials are monogrammed in tiny diamonds. This is the fancy side of Grandma, solid, conventional, ladylike. The other side could be represented by an acorn, or a clamshell. You could put an acorn and a clamshell, and perhaps a runty little apple as well, on a table next to the watch, and you would have the chord.

Grandma told my aunt Claire that she first saw Stanford through the keyhole in the door to her father’s law office, there in the Smithtown House. It was 1880. He was twenty-seven and was already a successful architect. She was eighteen. Edward Simmons, a painter who was Stanford’s contemporary and occasional collaborator, described him in a memoir as six feet two with “very long legs, broad shoulders, narrow hips, stiff tawny hair standing straight up, a great red moustache, beetling light eyebrows overhanging little bright grey-green eyes with almost white lashes,” and added, “His hands were large and strong and hairy with long blunt fingers.” The man Grandma saw through the keyhole was an artist, something that had not yet appeared in the mangrove swamp of Smith genealogy.

So there is Grandma, enclosed in her father’s house—the crooked old lines, the cosmopolitan additions, the cage in the attic—which is itself enclosed in the universe of Smiths. There she is, peering into her father’s inner sanctum, and there is Stanford, a man of volcanic creative energy, surrounded by her father’s law books. Those same books were there when I was a child and are there still. They are bound in leather that is slowly flaking in the humid Long Island climate: Voorhys’s “New York Code, 1855,” Cranch’s “Reports,” Pomeroy’s “Equity Jurisprudence.” Grandma told my Aunt Claire that when she saw Stanford through the keyhole she had a desire to run her hand over the bristles of his hair. Soon Stanford began to court her and she took him for a ride in a pony cart, driving fast over a bump in a way that she knew would pop him right out of his seat.

Stanford and Grandma were married in 1884, and lived in New York, first in rented rooms on East Fifteenth Street and then in a rented brownstone on West Twentieth Street. In 1885, they had a son, Richard Mansfield White, who died at seven months. They first rented the farmhouse on Carman Hill for the summer in that sad year. Even while it was still a rental, Stanford began fooling with the grounds. A Reverend Timothy O’Slap complained in a local newspaper that while walking through the countryside he had passed Carman Hill and had found “a low and curious seat” situated there by “the husband of one of the daughters of Judge Smith.” The seat was “surrounded by classic statues absolutely devoid of all clothing and standing out in shameless and conspicuous nudity among the green trees,” he wrote, and he and his party had “fled in confusion.”

Aunt Cornelia died in 1886, leaving to Grandma’s mother, Sarah Clinch Smith, a quarter of a million dollars outright, plus a quarter of the residue of her estate, which the New York Times estimated to be worth five million dollars. A hundred thousand dollars, the equivalent of five million today, was left to Grandma. When Sarah died in 1890 (the Judge had died the year before), she left the equivalent of twenty-five million dollars to Grandma. Thereupon the Stanford Whites bought Carman Hill Farm, and Stanford went to work in earnest to transform it into the phantasmagorical world of Box Hill. First, one gable was added to the farmhouse. At this stage the house still looked rustic—bonnety with deep eaves and big-footed with porch. Two more gables went up, and the clapboard yielded to pebbledash—large pebbles flung into walls of wet cement. On this expanded scale the yokel proportions mysteriously became elegant. Box Hill is a sleight of hand.

* * *

After Stanford was murdered, in 1906, Grandma stayed on at Box Hill for almost three decades. There has never been an accounting of what happened to Grandma’s fortune—under law, Stanford had control of it—but it was considerably reduced by the time of her widowhood. Still, my great-grandmother ran the house “like a Swiss watch,” as my mother put it, with peonies in cut-glass vases, and a merry butler, in a striped cutaway, who liked children. Grandma ran Box Hill at full tilt as a monument to Stanford (or, as she referred to him usually, “Stanford White”). Although the contents of the Gramercy Park establishment were auctioned off, Grandma kept Stanford’s eclectic collection in Box Hill more or less intact. She subsidized Box Hill with what little remained of Aunt Cornelia’s money, and sometimes by selling off parts of her own collection of lace. My mother remembers Grandma setting out on expeditions to New York auction houses, getting into the back of her black Ford—Morton Treadwell, her black chauffeur, magnificent in his uniform in the front—with a packet of her lace which she would then put on her lap. On our walks, Grandma White used to show me Queen Anne’s lace that grew in the fields, but only in adulthood did I learn from my mother that she had collected lace, and very expertly, though this was not celebrated in the family in any way. In the choreographic swirl of ornamental objects that make up the family universe of things, lace is incongruous: so feminine, not asking for attention; so retiring.

Morton Treadwell was part Native American, enormous, and very handsome, and he and Grandma were, in a certain way, close. They would go clamming in a beat-up scallop boat: he would row her out to the sandbars that appeared in the middle of the harbor at low tide, and they’d both dig there. Morton’s Native American ancestors were local—were probably Setaukets—and my mother believes that Grandma’s bond with him arose from a shared ancestral sense of place. It’s a picture in which the Smith centuries merge with an even more extraordinary place-rootedness that went back untraceably into mists. Morton was also descended from local slaves, and in this too, my mother quixotically feels, he shared roots in the “old days” with Grandma which erased their differences in station. Grandma and Morton went on “Long Island vacations,” as Grandma called their trips, during which they motored around to villages that were twenty, thirty, maybe fifty miles away from Box Hill and where Grandma would stay in a guesthouse, or a small hotel, and Morton would stay with one of his many relatives who were conveniently scattered all over the island.

In the neighborhood, Grandma was seen not as a person who went clamming in an old scallop boat—the way we saw her—but as a dowager queen, chauffeured around by Morton in his glorious uniform, she in a hat with a veil and wearing gloves and with calling cards to leave. In the neighborhood, she was perceived very definitely as a person with a story, including the story of Aunt Cornelia’s fortune, and also including the Stanford story; in the neighborhood version of that story she rose above misfortune with the aid of character and good breeding. There is still a tendency in the neighborhood to feel hurt puzzlement that God should have allowed such an off-color disaster to happen to a daughter of Judge Smith. Old-timers in the neighborhood—though only just born at the time of the murder, or not yet alive—will still shut out inquiries into that disaster in a kind of inherited loyalty to Grandma. To neighbors and Smith relatives the idea is that Stanford had terrible manners—it’s bad manners to get shot and have your sex life in the paper—whereas Grandma, coming from solid Smith stock, had solid good manners that carried the day. The element that is consistent inside the family and out is that, whether she was clamming or leaving calling cards, Bessie Smith White was just fine.

In the late thirties, Grandma began to turn Box Hill over to Papa and Mama and their large family of eight children—though she let go of it reluctantly. In early March of 1938, she went to a spa in Augusta, Georgia, where her sister Ella was escaping the cold, and wrote back to Mama, her daughter-in-law, at Box Hill:

Of course, now is the time, when I should turn over “Box Hill” to you and Larry—but no! I am naughty, unreasonable and very much ashamed of myself, and I just can’t help it! Stanford seems to stand beside me, whenever I go there—he created and loved it so—and I can’t even after all these years think of deeding it away, even to his son! I asked a lawyer if it would make any difference because of “Inheritance Tax” whether I gave it to you now, or in my Will, and he assured me, it would not—so you and Larry must try to forgive me, and let me go on leading this “dog in the manger” existence, and all I can do, now,—dear Laura—is to give you full power to do whatever you like with the place (only let me keep my room apart until I have time to really clear it out)—Please try to feel that it is “home”, as much as Larry does. You have waited so long and so patiently for that “Home”, and I have always realized how difficult it was for you to live in somebody else’s home. It makes me so so happy to know that my darling Grandchildren will grow up there and learn to love it too, and I don’t think, dear Laura, that anything you might say or do, could annoy me, or mar my love and great admiration for you! Sentiment does not count for much in this present troubled world, but I do not belong to this age—so remember that if a lump comes into my throat and I burst into tears while at “Box Hill”—it is certainly not from anything you and Larry have said or done—but just because I am a weak old thing, and am thinking of my gay and festive House as it was 50 years ago—there—it is easier to write these things than to say them—so—no more—but I know that you and I understand each other—and Larry can think me as unreasonable as he chooses, and has a perfect right to—finis.…

As to the Box bush, I think we can move it in April … but not to the north—it will die.

Soon thereafter, Grandma moved into the White Cottage.

Claire Nicolas White has recorded in a personal history of the Smiths called “The Land of the Smiths” how in old age Grandma wore raggedy clothes more and more, and became preoccupied with old things having to do with her childhood. There was some old furniture in the attic of one of the barns on the Smithtown House property, for example, and she told Claire she could have any of it that she wanted. But when Claire chose a broken-down chair with a velvet seat, Grandma said she couldn’t have that, because her father, the Judge, used to sit in it when he took off his boots in the evening. (The next day, though, she had the gardener deliver it to Claire.) In Claire’s history, Grandma is described sitting on the porch at one of the many birthday parties of my cousins who lived in the Smithtown House. Oblivious of the small children milling around her, she was lost in reverie as she cracked nuts with a huge nutcracker that had belonged to her father.

In the nineteen-fifties, big Sunday and holiday lunches in the dining room at Box Hill would include whoever of my mother’s generation was around and usually quite a few of my generation as well. A family story about Grandma White is that when in her mid-eighties she became bedridden she always called Box Hill from the White Cottage at 1:10 P.M. on those days, just after everyone had started lunch, and when the call was announced Papa, sitting at the head of the table, would roll his eyes. The rest of the story is that on July 4, 1950, the call came that Grandma was dying, and Papa, at the head of the table, rolled his eyes. I don’t remember this. What I remember is my uncle Peter striding into the dining room and announcing, in a loud, emphatic voice, “Grandma White is dead!” And then everybody at the table said “Aw!” in what sounded to me a falsely sad way (actually her death was merciful and had been expected) and then went on eating and talking. What seemed like a lid the size of the sky descended on me.

When the word “grief” is mentioned, or when I am sad for no apparent reason, that moment when Peter announced Grandma’s death is what comes to mind. Peter said that Papa had been “with” Grandma at the moment of her death, and I always think of that as well: I remember looking at Papa’s empty chair at the head of the table and thinking, He was “with” her. Did he hold her? Some days before her death, I had been brought to her room to say goodbye—though no one explained that this was the purpose—but the moment turned out to be not right. I glimpsed her through the open door, however: gray, in duress, but stoic in a groaning physicality. I wished for some spark of protest to fly from her to me, a spark that I could fan with my breath in cupped hands: for some essence of her being to flash out of the deep forest of her composure in defiance of what was happening—a demonstration of essence to affirm the defiant essence in me. But there was only numb acceptance. These pictures are still fresh, and I wonder now, What is it that keeps this old grief for a beloved great-grandmother, who died in the fullness of years, still unfinished?

The dining room at Box Hill had windows along one side and a wall of Dutch tiles along the other. The tiles were white, in different shades, with small figures of farms, animals, and people in a hot blue that flashed in the northern light from the windows. The tiled wall was bayed in the middle to make a fireplace: in daytime the flames were transparent with hot blue flashes all around. Near the windows, there were small gilded lions leaping upward from globes, and majolica plates running around the top of the room. On the end wall, behind Mama’s place, there was a round mirror in a heavy, gilded frame. The mirror itself was convex, and reflected, in a miniaturized and distorted way, the entire room, including everyone at the table. The frame was elaborate and topped by an eagle with outstretched wings. It was the anchor in a room that whirled with joy.

With a transcendent eye, I see myself in the moment of the announcement of Grandma’s death reflected in that mirror surrounded by family and history in that festive, ornamental room. And what I feel is rebellion against the fact that a person can go to the grave with so much buried within her. I feel fear to know that the forces of life do not necessarily rescue us, cannot be counted on to drive us out of our coverts into the open air.