9

Geopolitics and Commodities

For most of this book, commodity markets have been assumed to be driven largely by economic factors and grounded in supply-and-demand fundamentals, though subject to informational opacity and speculative mania. However, the sad reality is that in many commodity market segments, politics can trump economics, and markets are heavily distorted by politically motivated factors. In this chapter we discuss some of the major political distortions affecting markets, particularly markets in energy:

- Resource scarcity and security

- Resource nationalism and national oil and gas companies

- Commodity producer cartels

- Energy subsidies

- Pipeline geopolitics

This list is not meant to be exhaustive or comprehensive. Another book (and there are many) would be needed to do justice to the complex relationship between commodity markets and the political systems in which they are embedded.

Resource Scarcity and Security

The terms “resource scarcity,” “energy security,” “peak oil,” or “energy independence” appear frequently in the political discourse of many countries. Because of the high dependence of modern economies on commodities such as oil and food, there is a constant fear of the vulnerability of society should such commodity supplies become disrupted or exhausted (figure 9.1). Dystopian visions of a post-apocalyptic society in which resources have run out (the topic of countless science fiction novels and films) have been potently exploited by fear-mongering politicians to drive policy.

Figure 9.1 The Economist magazine proclaims the end of the oil age.

Source: Reproduced by permission of The Economist Newspaper Ltd., London (Oct. 23, 2003).

These Malthusian visions of resource scarcity, however, have been repeatedly disproved throughout history by the forces of economics incentivizing the search for new commodity supplies and substitutes. Nevertheless, economic (remember the low price elasticities!) and political sensitivities have made the provision of “resource security” a universally desired public good demanded of all modern governments by their constituents (figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2 Soviet propaganda poster: “Soviets and Electrification Are the Foundation of the New World!”

“Resource security” is a term that is used loosely in many contexts but can be roughly defined as the provision of affordable, reliable, accessible, and sustainable sources of resources. These various factors are in constant tension with each other. Yet the ultimately fallacious nature of many arguments around resource security should not cause us to underestimate their political potency or the very real political distortions currently existing in many commodity markets.

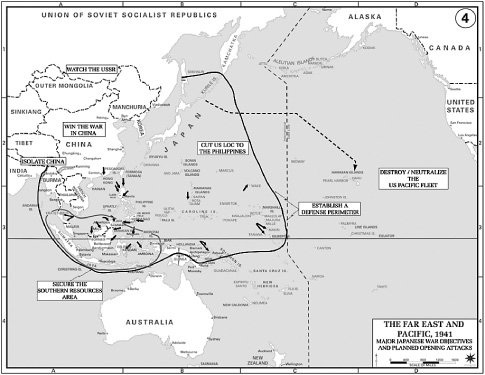

Indeed, in many ways, some of the most cataclysmic human events were caused by fears around resource security. World War II can be partially viewed as driven by overly simplistic views of resource scarcity in Nazi Germany (Lebensraum) and imperial Japan (Southern Resource Area), whose leaders thought the direct military conquest and control of energy, food, land, rubber, tin, and other commodity resources was an existential prerequisite for the survival and eventual triumph of their nation or race. Certainly, those views shaped the direction of their military campaigns, and the loss of oil supplies proved to be a major and possibly even decisive factor in the ultimate defeat of the Axis powers.

Figure 9.3 Securing the “Southern Resources Area” was a key component of Imperial Japan’s 1941 war objectives.

The postwar economic experience emphasizes the intellectual bankruptcy of these “zero-sum” or “mercantilist” views of resource security. Relatively resource-poor nations such as Germany, Japan, South Korea, China, and India (among others) have seen remarkable economic postwar growth, while resource-rich nations like the former Soviet Union, the Congo, and Venezuela have lagged. This is in part thanks to the free flow of goods and services in the global trading system, which allows resource-poor economies to trade their output for commodities.

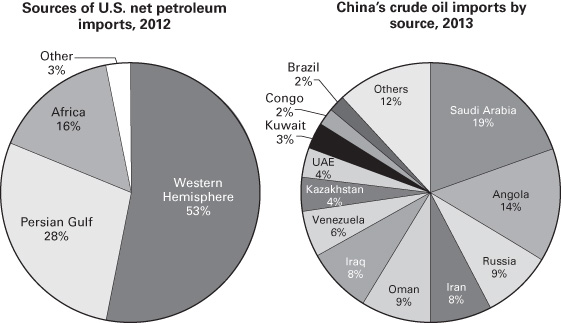

Yet the intellectual descendants of these views, whether under the rubric of “peak oil” or “energy independence,” remain embedded in the popular discourse today. Those calling for U.S. “energy independence” demand the United States wean itself off dependence on imported “foreign” oil. This political sound bite is based on a misconception that the U.S. energy market is autarkic and nonintegrated with the rest of world. In fact, the United States is relatively less dependent on imports, particularly on unreliable Middle Eastern imports, than China, especially after the onset of the U.S. unconventional hydrocarbon revolution (figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 U.S. vs. Chinese dependence on foreign oil.

Sources: Left, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Petroleum Supply Monthly, February 2013. Right, Global Trade information Services, FACTS Global Energy.

But ironically, this dependence means virtually nothing from a resource security perspective. As oil is a fungible commodity and its markets are globally integrated, U.S. and Chinese consumers face the same (pre-tax) global price of oil, no matter what their import dependence may be. Any difference would cause the free market to shift supplies to arbitrage that price spread.

The example of the 1973 OPEC embargo is instructive. In a gesture of support to fellow Arabic nation Egypt during the Yom Kippur War with Israel, the Arab members of OPEC categorized countries into friendly, neutral, and unfriendly status. Unfriendly countries such as the United States and the Netherlands that remained publicly supportive of Israel would face a complete embargo. Meanwhile, friendly countries such as the United Kingdom, France, and Japan (which did a rather craven about-face) would enjoy full access. This distinction did not help the “friendly” countries become more immune to the oil shock; all faced the same price hike. A similar circumstance occurred during the more recent Libyan revolution in 2011. Most Libyan oil goes to Europe, but American and European consumers faced the same price increases as supplies that would have otherwise have gone to the U.S. market were diverted to Europe (box 9.1).

Box 9.1

Fat Tails, Power Laws, and Oil Markets

Geopolitical shocks to oil markets, such as the 1973 OPEC embargo, the 1979 Iranian Revolution, or the 1980 Iran-Iraq War, are often blamed for causing extreme fat-tailed events in the behavior of oil markets. But recent research suggests that these are not isolated “black swan” events but part of a broader pattern of non-Gaussian “power law” distributions seen in an extraordinary variety of economic and physical contexts, such as income distributions, the size of cities, executive pay, the frequency of words, and the metabolic rate of biological organizations.

The Gaussian distribution, also known as the normal distribution or the “bell curve,” is also universal in the natural and social sciences. Its ubiquity is driven by the central limit theorem, which posits that, under certain regularity conditions, the normalized average of random variables drawn from any probability distribution converges to that of a Gaussian distribution. Popular financial models such as the Black-Scholes-Merton formula or the Sharpe-Markowitz mean-variance model typically assume normal or Gaussian probability distributions for price returns. These have “thin” tails, with the cumulative probability for large σ events declining rapidly to zero.

By contrast, power-lawed or Pareto distributions have thick tails, with the probability of large σ events declining, as the name suggests, according to a power function. A power law, also known as a scaling law, is a relation of the type  , where Y and X are variables of interest,

, where Y and X are variables of interest,  is called the power law exponent, and k is some constant. (A power law with

is called the power law exponent, and k is some constant. (A power law with  is sometimes known as Zipf’s law.)

is sometimes known as Zipf’s law.)

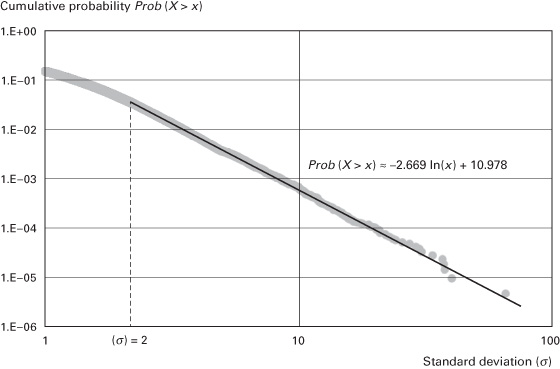

Empirically, to precisely measure the degree of non-Gaussian fat tails in crude oil markets, we need a very large number of data points to get sufficient observations of large σ events, which by definition are extremely rare. Figure 9.5 plots the cumulative probability of large σ return events plotted on a logarithmic scale using a database of more than 47 million observations of high-frequency prices for WTI crude oil prices from the beginning of 2000 to the end of 2008.

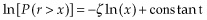

If crude oil price returns were indeed power-lawed rather than Gaussian-distributed, then the probability that oil price returns exceeds an amount x standard deviations away from the mean should be a log-linear function of the natural log of x:

As we can see from figure 9.5, for return events exceeding two standard deviations (two sigma or higher) from the mean, a log-linear function with a power law coefficient of about 2.7 does an excellent job of fitting the empirical distribution of oil price returns, including one 65-sigma event!

Hence, far from being isolated exceptions to the normal Gaussian distribution, oil markets feature highly power-lawed distributions in their tails. Despite their analytical tractability and popularity, economists are reexamining the assumptions of standard Gaussian behavior for the prices of many commodities and other financial assets.

Figure 9.5 Cumulative probabilities of high sigma events in crude oil price returns on a logarithmic scale.

Indeed, if the United States truly wished to strengthen its energy security and build some resilience against foreign oil shocks and other political externalities, imposing higher Pigovian taxes on imported oil would help. The imposition of a tax would reduce the volatility of after-tax prices faced by consumers and businesses, helping them with investment planning and financial decision making. It would divert tax revenue toward the U.S. Treasury instead of toward the coffers of oil exporters, some of them geopolitical adversaries, such as Russia or Iran. It would also economically stimulate domestic production, energy efficiency, and the search for technological substitutes. Any additional financial burden caused by higher after-tax fuel prices could be offset by vouchers for lower-income households and reduced income or corporate taxes. Yet this proposal remains politically dead on arrival as no politician wants to advocate for higher headline prices at the fuel pump. This economic tone deafness represents one of the greatest missed opportunities by U.S. policy makers.

Of course, markets do best at ensuring resource security if goods and services can move freely as competitive economic forces dictate. It is when political factors prevent this free movement that concerns over resource security are justified. For example, during wartime, military blockades and embargoes can physically cut off supplies from markets no matter the economic logic. Indeed, blockades were a key military strategy used with remarkable success against Germany in World War I and Japan in World War II. Hence the world’s navies constantly monitor and patrol maritime chokepoints, such as the Strait of Hormuz or the Strait of Malacca, to maintain the free flow of oil supplies against any threats (figure 9.6).

Figure 9.6 Maritime oil flow chokepoints: daily transit volumes.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

But even in peacetime, economic forces may not be given free reign. We discuss some of the most egregious distortions in energy markets, including the rise of state-owned resource companies, next.

Resource Nationalism and National Energy Companies

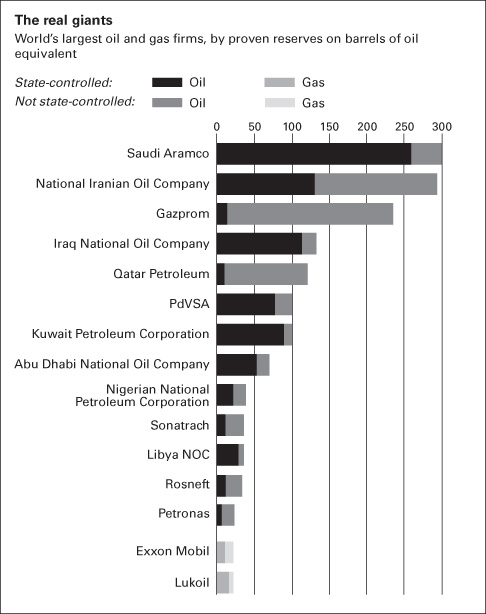

Perhaps the most extreme yet often underappreciated political distortion in the global energy market is the lack of free competitive access for the bulk of the world’s proven (and cheapest) oil and natural gas reserves. Instead, the development of these reserves is restricted to state-owned enterprises, also known as national oil (and gas) companies (NOCs).

This fact is surprisingly obscure to the public, which tends to think of the major international oil companies (IOCs) such as ExxonMobil or British Petroleum as “Big Oil.” But in fact, in terms of holdings of reserves, the IOCs are minnows compared to NOCs such as Saudi Aramco, the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), Venezuela’s PdVSA, and Russia’s Gazprom. Figure 9.7 shows the estimated hydrocarbon proven reserve holdings by company, underscoring the discrepancy between NOC versus IOC reserves. This suggests that an astonishing 90% of the world’s known oil and gas reserves are being monopolized by NOCs. These figures likely underestimate the size of NOCs’ oil reserves, as NOCs choose to keep the true size of their oil holdings opaque, and full geographic surveys may have missed further reserves.

Figure 9.7 The real giants: world’s largest oil and gas firms, by proven resources (in barrels of oil equivalent). National oil companies control 90% of the world’s reserves.

Source: PFC Energy, reproduced in the Economist in 2006.

Ironically, these NOCs arose amid a political backlash against Western imperialism, which supported once powerful companies such as the Anglo-Persian Oil Company or Standard Oil (the ancestors of today’s IOCs) in developing indigenous resources in their colonies on financial terms extremely unfavorable to the weak host governments. The predatory behavior of these companies, which reaped the lion’s share of revenue while giving only pittances to the local community, motivated a deep sense of political grievance. After many new resource-rich nation-states emerged out of the wreckage of European empires after World War II, “resource nationalism” came into vogue. The newly independent states formed NOCs to best utilize and preserve the value of mineral wealth for the local society and keep it out of the reach of predatory foreign companies.

Today the vast majority of the world’s energy resources remain under the control of NOCs, which maintain a dual mandate of maximizing resource value and creating local jobs and funding welfare programs.

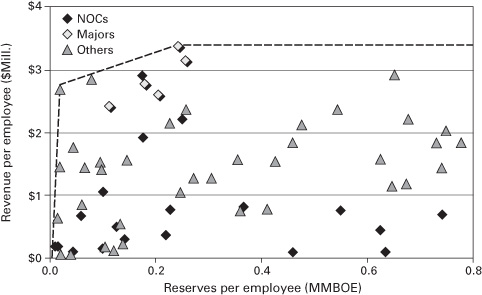

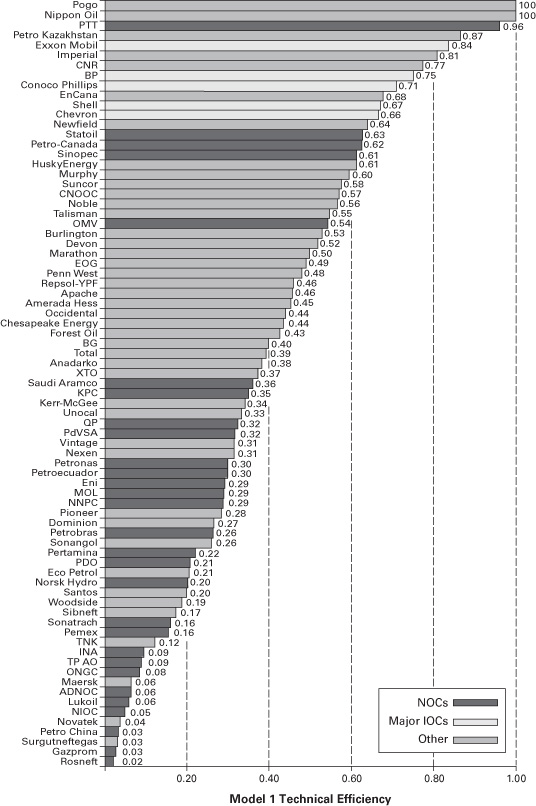

With a lack of competitive pressure because of their protected monopoly status and their dual mandate, it should be no surprise that NOCs have a dismal record of operational efficiency compared to their private counterparts. In 2007 the Baker Institute of Public Policy at Rice University produced a report that detailed the technical efficiency of oil companies by measuring the distance from an “efficient frontier” calculated in terms of revenue and reserves per employee, as seen in figures 9.8 and 9.9 (with 1.00 on the axis being at the efficient frontier, and lower numbers representing less efficiency).1 NOCs were shown to be generally far less operationally efficient than IOCs at maximizing revenues, in light of the amount of reserves they possess.

Figure 9.8 Operational efficiency of oil companies.

Figure 9.9 Distance to the efficient frontier. Output = revenue; inputs = gas reserves, oil reserves, employees.

Moreover, the direct economic costs of this technical efficiency may pale in comparison with the indirect costs associated with a lack of access to reserves by competitive markets. It is difficult to accurately estimate this indirect cost as one must imagine a counterfactual world in which all oil reserves are subject to free and open competition and bidding.

But it is plausible that in this more liberal world, given the incredible concentration and bounty of proven hydrocarbon reserves in the Persian Gulf, where development costs are as low as $2 per barrel, the full power of modern technology and capital investment would have brought global oil prices in equilibrium to perhaps $10–$15 per barrel. Of course, because of the lack of access resulting from NOC monopolies, global oil prices have instead been in the $50–$100 range for the past few decades with short exceptions.

A simple back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that a $40 price distortion in the global oil market amounts to an economic transfer from consumers to producers of $1.3 trillion annually. This distorted price in turn incentivizes private oil companies locked out of the most economical reserves to develop higher-cost sources, such as offshore, Arctic, and shale/tight unconventional oil. All those billions of dollars in global exploration and production may represent an economic distortion away from the economically ideal free-market equilibrium.

An intelligent observer from Mars may only shake its alien head at the collective folly of humanity as it sees us busily extracting and exhausting oil reserves in the most expensive, environmentally damaging, and technically most challenging areas of the Earth’s crust, even as the easiest reserves remain underdeveloped. In a supreme irony, it is possible that in the future, the exhaustion of those hardest-to-reach oil reserves may spur the technological breakthroughs to alternative energy sources, making the oil in the most accessible and economical reserves obsolete, thanks to political distortions.

Commodity Producer Cartels

If the political distortions in the market for developing oil reserves (when the commodity is still underground) weren’t enough, there are further political distortions affecting oil markets once the reserves have been developed and production capacity has been built.

Many of the same states that have created NOCs have also joined together into a supranational entity known as the Organization of Oil Producing Countries (OPEC). OPEC seeks to restrain production below capacity by setting production quotas for its member states to stabilize prices and extract further oligopolistic rents. While precise estimates are challenging to derive, the economic distortion from this explicit political manipulation of supply may still be much smaller than the indirect distortion stemming from lack of competitive access to develop the world’s reserves and build production capacity in the first place.

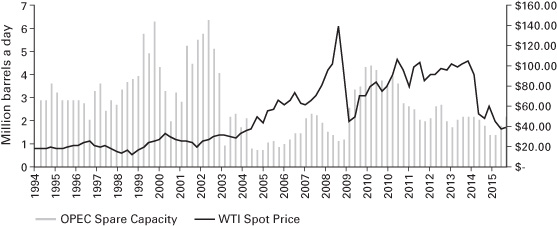

However, OPEC is far from a perfectly monolithic organization, with geopolitical rivalries and the free-rider problem often causing its political unity to fall apart, as happened during the November 2014 meeting. With no rigorous mechanism of enforcement (unsurprising, given its supranational nature), production quotas set by the group can and are flouted by individual member states, ironically often by the same “hawks,” such as Iran or Venezuela, that constantly call for tighter quotas (on others) and higher price targets (figure 9.10).

Figure 9.10 OPEC spare capacity vs. WTI spot prices.

Source: Bloomberg.

Saudi Arabia, as the largest and wealthiest holder of oil reserves with the economic and political will to maintain unused or spare production capacity, acts as the de facto leader of OPEC. It aspires to act as a “central bank” of oil, increasing or holding back output from its spare capacity, to bring price stability into markets (though at noncompetitive and elevated levels).

But this is notoriously challenging because of the naturally high volatility of oil prices, the inelasticity of demand and supply, the inability to immediately produce beyond installed capacity, the difficulties in coordinating politically with other producers (some of which, such as Russia or Iran, are geopolitical rivals), low transparency in both supply and demand, and surprises from non-OPEC production (such as the U.S. fracking revolution).

Nevertheless, to properly act as a “central bank,” Saudi Arabia may wish to borrow from the playbook of modern central banks such as the U.S. Federal Reserve, which places immense emphasis on transparency to maintain its credibility and power to move markets. By contrast, the lack of transparency and openness in Saudi Arabia’s energy sector leaves the window open for investor disbelief. This notably occurred in 2008 when oil prices were skyrocketing to $150/bbl. In an attempt to temper the oil price, Saudi Arabia announced the emergency additional production of 400 kb/d at an extraordinary meeting in Jeddah. Yet markets shrugged off this announcement, believing that Saudi Arabia lacked the production or reserve capacity to actually bring this additional supply to market. Ironically, by the time this production indeed came online, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers had triggered the global recession and subsequent financial crisis, and oil prices had plummeted. In turn, the recent planned partial privatization of Saudi Aramco and the corporate transparency that accompanies a public listing mark a potentially revolutionary change.

Energy Subsidies

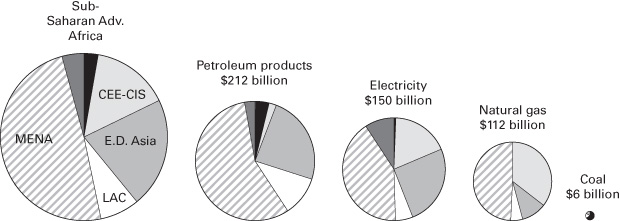

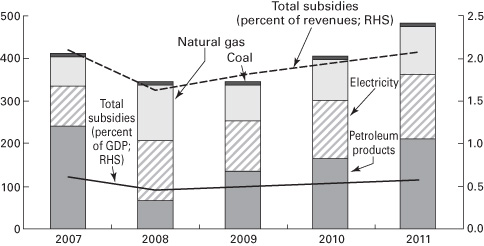

Political distortions of energy markets are by no means isolated to the supply side of the equation. Demand can also be distorted by programs to subsidize fuel prices below market levels, often by the very same producers that are distorting supply. The International Monetary Fund estimated the costs of these negative fuel taxes at about $480 billion per year in 2011 (figures 9.11 and 9.12).2 By contrast, renewable energy subsidies, mainly from the governments of the advanced economies, amounted to $120 billion in 2014.3

Figure 9.11 Share of total subsidies. Total pre-tax subsidies amounted to $480 billion in 2011.

Source: Benedict J. Clements, David Coady, Stefania Fabrizio, Sanjeev Gupta, Trevor Serge Coleridge Alleyne, and Carlo A. Sdralevich, Energy Subsidy Reform: Lessons and Implications (International Monetary Fund, 2013).

Figure 9.12 Total subsidies as a percent of revenues and GDP.

Sources: Staff estimates, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Energy Agency, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, the IMF’s World Economic Outlook, and the World Bank. Data are based on most recent year available. Total subsidies in percent of GDP and revenues are calculated as total identified subsidies divided by global GDP and revenues, respectively. As reproduced in Clements et al., Energy Subsidy Reform.

The list of economic harms caused by this distortion is long. Fuel subsidies cause fiscal deficits, crowd out needed social spending in other areas, depress private investment in deploying more energy efficient technologies, and incentivize the wasteful use of energy.

Worse, even though subsidies are often justified as being a redistributive program for low-income households, they benefit the richest consumers the most (in absolute terms). The rich own and use cars and other energy-intensive equipment more extensively than the poor do. Figure 9.13 shows how 61% of the economic cost of gasoline fuel prices goes to the richest 20% of the income distribution. Yet paradoxically, in relative terms, subsidies form a larger share of the effective income of the poorest consumers, and doing away with fuel subsidies would hurt the poor more than the rich in relative terms.

Figure 9.13 Distribution of fossil fuel subsidies to income groups by quintile.

Source: Arze del Granado, Francisco Javier, David Coady, and Robert Gillingham, “The Unequal Benefits of Fuel Subsidies: A Review of Evidence for Developing Countries,” World Development 40, no. 11 (2012): 2234–2248.

However, with the fall in oil prices since 2014, many countries are making progress toward reducing energy subsidies. Exporter nations face pressures on their budgets, while importing nations can phase out subsidies and consumers still face still historically moderate market prices for oil.

Pipeline Geopolitics

Finally, some unique political distortions occur in natural gas markets. Unlike oil, which is liquid and thus easily transportable, natural gas is gaseous at room temperature. Transportation therefore requires either compression or cooling into liquid form or the construction of dedicated pipelines, both of which are costly. This is why natural gas markets, unlike oil or coal markets, are not yet globally integrated but are balkanized into various market pockets with their own idiosyncratic price dynamics.

Figure 9.14 compares the relative transport costs of shipborne oil and coal, oil and gas pipelines, and liquefied natural gas (LNG). At intermediate distances of 5,000 kilometers or less, pipelines represent the most economical form of transportation.

Figure 9.14 Indicative comparison of fossil fuel transportation costs. The main determinants of gas transportation costs within the ranges indicated are for gas pipelines, the diameter of the pipe and the terrain to be covered, and for LNG, the initial costs of liquefaction capacity.

Source: Adapted from Jensen Associates, reproduced by the International Energy Agency.

But pipelines are expensive to build, and operators of existing pipelines form “natural monopolies” as a result of the barriers to entry faced by potential competitors. Furthermore, gas pipelines are fixed assets that often cross national borders. Therefore, countries whose territories the pipeline transits also possess the ability to block the flow of gas through the pipeline.

This creates what economists call a “hold-up” problem, in which two or more actors must cooperate to create economic value but contracts between them are nonenforceable. Then any actor may have the incentive to “hold up” the project and destroy its value to increase its bargaining power and win a greater share of the revenue.

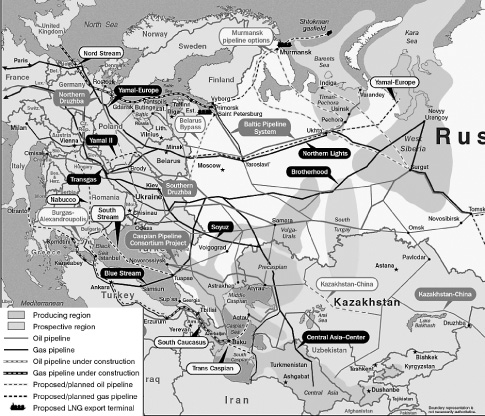

Nowhere is this problem more evident than in the natural gas pipelines crisscrossing the Eurasian landmass, notably those linking Russia to Western Europe (figure 9.15). Many of these pipelines were originally built by the former Soviet Union to send the natural gas from its western Siberian fields to its population centers in the western USSR and beyond, to gas-hungry customers in Germany and other parts of Western Europe. While the Soviet Union existed, there was no political distortion to impede the smooth flow of gas, at least in Soviet territory. But with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of independent states such as Belarus and Ukraine through whose sovereign territory these pipelines transited, the situation was ripe for the hold-up problem to emerge.

Figure 9.15 Eurasian pipelines.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2009.

For example, after signing an agreement to supply natural gas at a certain price to customers in Germany, Russia’s state gas monopoly, Gazprom, may be tempted to renege on the contract and hold out for better rates. From Germany’s perspective, it may be better to capitulate than see its gas supplies interrupted. Or Ukraine might halt the flow of gas through its territory to bargain for higher transit fees or lower prices on its own gas.

The headaches around gas security have forced countries in Western Europe to search for more reliable alternatives and build resiliency into their natural gas supply system, including through the construction of regasification terminals for imported LNG and more storage and interconnecting pipelines. In turn, Russia has poured billions of dollars into developing alternative pipelines that bypass problematic transit countries like Ukraine, such as the Nord Stream under the Baltic Sea or the planned South Stream pipeline under the Black Sea. These moves in turn have angered the United States, which is concerned by the improving bargaining power of Russia relative to Ukraine’s and the increasing vulnerability of U.S. allies in Western Europe to further energy blackmail by Russia.

All of these additional pipelines and infrastructure are not the ideal outcome, as expanding existing pipelines would have been far more economical. They exist only because of the peculiarities of natural gas markets. But until a mechanism can be found to enforce natural gas contracts between sovereign entities and minimize the hold-up problem, such political distortions are likely to continue.

.

.