10

Commodity Markets and Financial Regulation

In this chapter, we return to some of the issues raised in earlier chapters about the proper role of regulation in improving the market efficiency of financial markets for commodities.1 We have already discussed the various reasons for participating in such financial activities as hedging, speculation, and portfolio investment. Ideally, these financial markets serve consumers and producers in managing their commodity price risk effectively and aid in economic decision making.

But the dizzying rally in global commodity prices in 2007 followed by their crash in 2008 added to skepticism over the proper regulation of commodity markets. First, as oil prices rose to a record high of $147.47/bbl in July 2007, many policy makers blamed the record amount of financial investment in commodities, notably by passive index investors, for the record-high prices. Warren Buffett famously dubbed derivatives the financial equivalent of weapons of mass destruction.

Subsequently, the onset of the worst global economic and financial crisis in a century, triggered by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, gave further impetus to regulatory efforts. Governments around the world stepped in to bail out troubled financial institutions, while regulators initiated a suite of reforms, such as the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 and the Third Basel Accord, to tame unruly financial markets.

We have also discussed the various imperfections in commodity financial markets that make them prone to behavioral anomalies despite the discounting of many experts. To recap, first, the demand for and the supply of many commodities are highly price inelastic and nonlinear. This is because a large supply or demand response requires high upfront fixed costs from producers and consumers (e.g., to open a new producing basin or upgrade the efficiency of equipment). In turn, even the slightest excess demand or supply would trigger violent price responses, making it difficult for market participants to formulate price expectations.

This situation, where there is naturally high volatility, is further worsened by the fact that commodity markets are notoriously opaque. As we saw earlier, the clear majority of proven reserves of crude oil and natural gas are kept by nontransparent national oil companies (NOCs), which divulge little information about their reserves. There are simply no credible data available for key aspects of the fundamental balance, such as the amount of Saudi spare capacity or the size of Chinese inventories.

The lack of insight into economic fundamentals forces information-starved market participants to copy the behavior of others, leading to herd behavior. The shortage of information also leads market observers to focus inordinately on the handful of available signals, such as weekly changes in U.S. inventories, even if they are misleading signals of the overall state of global demand or supply.

And the paucity of reliable information can lend dangerous plausibility to some of the wilder narratives on commodity fundamentals (e.g., peak oil). And despite the idealistic hopes of economists that any mispricings should quickly be arbitraged away, the inelasticity of supply and demand may prevent the visible physical response necessary to persuade market participants otherwise. The traditional mechanisms that would cause prices to return to true equilibrium levels, namely, efficient absorption of information and physical adjustment of markets, can be weak in the short term. Furthermore, speculative behavior can further exacerbate this unnatural volatility, especially if it drives the mispricing in a single direction, resulting in the formation of asset bubbles.

Bubbles typically begin with some plausible if ill-understood theory behind the increasing fundamental value behind some asset or commodity. For instance, uncertainty around the internet revolution led to the dot-com bubble, which burst in 2001, and the Dutch tulip bulb mania in 1637. New “speculative” demand linked to prices enters the market, with investors seeking to sell to the “bigger fool” rather than assess the true equilibrium value of the commodity.

Eventually, of course, economic reality sets in and the excess supply in the good or commodity is finally recognized, resulting in the rapid collapse of prices and the destruction of trend-following speculative demand. But in the meantime, this volatility can cause massive damage to the economy through the collapse of systemically important financial institutions and the ruin of many retail investors unlucky enough to be caught up in the speculative frenzy. If the bubble occurs in sensitive “staple” goods like food or energy, the political temperature can rise quickly.

Politicians often like to ask sophistic questions, such as “Does speculation drives prices?” This is as meaningless as the question, “Does law cause crime?” On the one hand, at a tautological level, law does “cause” crime as without laws, there would be no such thing as a crime. Similarly, speculation naturally drives prices as traders transmit the information into market prices through the very act of trading. This is simply part of the mechanical process of buying and selling in any well-functioning market. But a more meaningful question to ask is, “How should one design/regulate markets to improve price discovery and minimize unnatural (if inevitable) deviations away from true equilibrium prices?” Despite Conant’s defense of speculation, he too understood and cautioned against uninformed speculators who could distort prices temporarily.

Rather than ideologically railing against speculation in general, regulators should consider policies that would nudge the obvious imperfections of commodity markets closer to the classical ideal of Charles Conant. These policies include regulations to ensure the following:

- 1. Good information entering into the fundamentals of demand and supply.

- 2. Freedom and willingness on the part of traders who do possess information to enter markets and transmit said information efficiently into prices.

- 3. Good market design to prevent market manipulation, rent-seeking, and financial illiquidity and systemic risk contagion.

Commodity Market Regulation in the United States

In response to the global recession of 2008–2009, the U.S. Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, the most comprehensive regulatory overhaul of financial markets since the Great Depression. In commodity markets, the Dodd-Frank Act mandated changes in four key areas:

- 1. Transparency, including disaggregated position reporting, large trade reporting, and real-time reporting of trade information in a data depository.

- 2. Centralized clearing of standardized swap contracts through a centralized counterparty clearinghouse.

- 3. Higher capital and margin requirements, especially for bilateral OTC swaps, following Basel III rules.

- 4. Position limits that limit the maximum size of trade positions in certain commodities by noncommercial participants, that is, “speculators.”

Let us discuss these four aspects of the Dodd-Frank Act in greater detail.

Physical Transparency

As discussed earlier, commodity markets inevitably feature large and unavoidable price swings. Forcibly suppressing them would only harm the efficient functioning of markets. Yet this does not mean that all price swings are fundamentally justified or desirable. The textbook role of a market price is to adjust to find the appropriate price level to equalize required demand for an economic good with available supply. The most basic ingredient for stable and efficient price discovery is public and credible information on the sources of demand and supply.

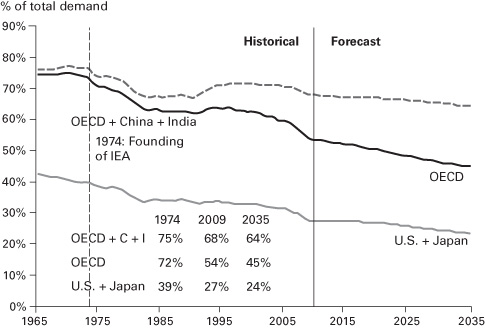

The current state of transparency in the many commodity markets, however, is decrepit. Here we may take the example of oil markets. Only a handful of advanced economies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provide any timely statistical releases on their oil demand-and-supply balances through their membership in the International Energy Agency (IEA). At the time of the IEA’s founding in 1974, OECD member countries accounted for almost three quarters of global oil demand. Today they account for less than half of the world’s oil consumption, and their share continues to fall quickly. Total world oil demand is projected to grow from roughly 90 million barrels per day at present to over 100 million barrels a day by 2035. But nearly all of that incremental increase is projected to come from non-OECD member states (e.g., China, India), where transparency is much poorer, decreasing the OECD’s share to only a third of global consumption by 2035 (figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 OECD share in global oil demand compared to other participants’ share. The OECD was founded in 1974.

Source: BP, U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Data on the supply side of the equation are similarly poor, with OECD member countries accounting for less than one quarter of the world’s crude oil production. Market production share is dominated by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the states of the former Soviet Union, none of which is particularly transparent. Together, they account for over half of world production. Even worse, while world oil demand is aggregated from the decentralized needs of millions of individual consumers, and therefore has at least some relationship to economic growth, production from OPEC and the former Soviet states has often been subject to the political calculations of NOCs.

Despite significant efforts to enhance the transparency of demand and supply statistics through such laudable initiatives as the Joint Oil Data Initiative (JODI), there is much room for improvement. Participation in JODI is purely voluntary, and there is no penalty for omitting or refusing to submit data. Further, the data submissions are not subject to third-party review or public scrutiny of the collection processes, leading to questions over the credibility and accuracy of the data.

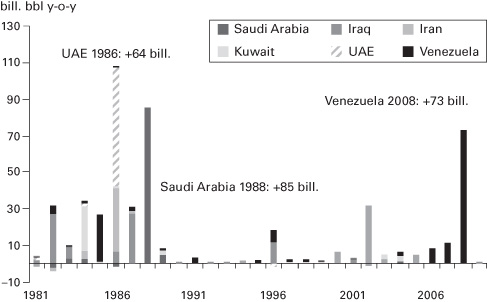

Members of OPEC, who operate an imperfect oligopoly and receive official production quotas proportional to estimated official reserves, can and are sorely tempted to fudge official production reports when politically expedient. For example, in 1984 Kuwait abruptly raised its official proven reserves from 67 billion barrels to 93 billion barrels. Other nations, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Iran, determined to maintain their own quota levels, followed suit. Figure 10.2 shows how key OPEC members have been manipulating their reserves statistics over the years in a bid to capture more production quotas. Nor is this behavior a thing of the past. As recently as 2008, Venezuela revised its official reserve levels upward by an astonishing 73 billion barrels.

Figure 10.2 OPEC members’ year-by-year revisions to official proven reserves.

Source: BP, U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Most mature financial markets have—after the hard lessons of numerous panics and accounting shortfalls—made a point to provide full, timely, and accurate accounting disclosures that are publicly available. An investor in U.S. equity markets, for example, may, when formulating a fair price, freely look up the cash flow, assets, and liabilities of a company by reviewing the company’s filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Energy market traders have no such recourse. Instead, they must extrapolate from incomplete, infrequent, and often inaccurate data to make intelligent guesses of the appropriate equilibrium price level.2

In an ideal world, the U.S. government could fix this problem by mandating physical transparency requirements of all companies that produce or consume oil traded on U.S. markets, just as it requires transparency from companies that are publicly traded in the United States. Yet this faces a fundamental problem: the prices of U.S.-traded oil contracts depend on the global balance between oil demand and supply, but the United States lacks the regulatory reach to require transparency on a global scale. Physical transparency in commodity markets is thus as much a foreign policy problem as it is a financial regulatory problem.

Financial Transparency

As with physical transparency, certain financial transparency initiatives hold great potential for improving market efficiency and deterring excessive risk taking and market manipulation. However, policy makers must also be alert to the real trade-offs inherent in substantial transparency initiatives and to the political opposition that will be engendered from the affected interests.

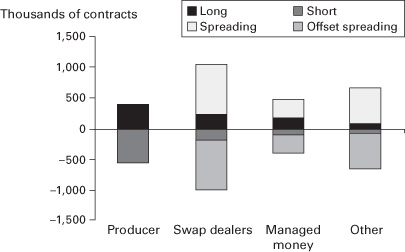

To achieve improved financial transparency, policymakers should improve the quality of statistical reporting and make statistics more accessible by creating a real-time data depository. On the statistical reporting front, the U.S. Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has made important progress by providing new disaggregated Commitment of Traders (COT) reports on a weekly basis since September 2009. These new reports provide a finer decomposition of trader’s holdings than previous reports, separating traders into the following four categories (Previously the CFTC used to classify market participants into “commercial” and “noncommercial” participants):

- 1. Producer/Merchant/Processor/User: An entity that predominantly engages in the production, processing, packing, or handling of a physical commodity and uses the futures markets to manage or hedge risks associated with those activities. Typical examples in the energy space would be an oil producer, a refinery, an airline, or a pipeline operator.

- 2. Swap dealer: A “swap dealer” is an entity that deals primarily in swaps for a commodity and uses the futures markets to manage or hedge the risk associated with those swaps transactions. Typically, large investment banks play an important role as swap dealers managing commodity financial exposure for their clients, which can include traditional producer/users but also hedge funds and other financial speculators.

- 3. Money manager: A “money manager” is a registered commodity-trading advisor (CTA), a registered commodity pool operator (CPO), or an unregistered fund identified by CFTC. These traders are engaged in managing and conducting organized futures trading on behalf of clients. This class arguably comes closest to the “financial speculator” often mentioned in the press. But it is important to note that a large proportion of speculative positions, including those from institutional investors into commodity indices, is likely made through swap contacts and shows up in futures markets only through swap dealers.

- 4. Other reportables: Every other reportable trader that is not placed into one of the other three categories is placed into the “other reportables” category. It is disconcerting that this category are increasing in size lately.

For each category, the CFTC provides the amount of long, short, or in spread (offsetting long and short) positions (figure 10.3).

Figure 10.3 Sample positioning data of long, short, and spreading positions in a commodity futures market by investor category.

Source: CTFC.

While a vast improvement from the previous classification of market participants simply into “commercial” and “noncommercial” categories, this system still exhibits considerable shortcomings. First, as the swap dealer category itself suggests, the COT reports cover only the futures market and not the vast and largely opaque OTC swaps market, which often trades “look-alike” contracts similar in function to standard futures contracts.

Second, the producer/merchant/processor/user and swap dealer classifications are still too broad. To take an example, an oil producer typically hedges by selling short some futures contracts to lock in a price for a set amount of sales. By contrast, an oil consumer, such as an airline, typically hedges by going long on futures contracts to lock in a price for a set amount of purchases. Together, a category that includes oil producers and consumers would see the natural short positions of producers and the natural long positions of consumers cancel each other out, making the net positions reported under this category difficult to interpret.

Similarly, the swap dealer category may wash-out many offsetting long and short positions held by the counterparties of the swap dealers. Ideally, reporting should be further disaggregated into producers, users, and processors, to prevent the washing out of natural long and short positions, while swap dealers should record and report those positions made on behalf of commercial operators, managed money investors, or other swap dealers.

The COT reports are also silent on the timing or “term structure” of market participants’ financial exposure. For example, current reports cannot distinguish between money managers forming positions in short-term natural gas contracts in response to, say, expectations of a temporary heat wave versus positions formed in long-term natural gas contracts in response to expectations of increased demand from China. But this difference matters to market stability.

For example, Metallgesellschaft AG, an energy wholesaler, failed in 1993 because of the unsustainability of the term structure of its risk management strategy. The large size of its losses (roughly $1.5 billion in 1993 dollars) and the forced liquidation of its massive positions caused systemic tremors throughout the financial system. This underscores the need for regulators to have a clear understanding of the term structure of aggregate commodity risk held by financial participants.

Real-Time Data Depository

In addition to improving the quality of statistical reporting, the CFTC also now mandates the creation of real-time post-trade swap data repositories (SDRs) to publicly report the date, time, trade size, price, and counterparty identities moments after every swap transaction. Not only does this shed reporting light on opaque markets and alert regulators of potentially dangerous risk-taking behavior but a real-time data repository promises to reduce price volatility by anchoring prices to the terms of previous transactions.

For example, any sensible customer would likely refuse to buy a crude oil contract at a price very different from $20 a barrel when she knows that literally moments earlier a customer before her paid precisely that. Furthermore, a real-time data repository would lower the customer’s costs of executing commodity financial transactions, potentially allowing more cost-effective risk management by physical companies wishing to hedge commercial risk or retail investors seeking exposure.

Such an initiative is not new for the financial industry. The Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE), which was introduced into the corporate bond market in 2002 by the U.S.-based Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), provided a natural experiment for financial economists to study the impact of such transparency on liquidity and market efficiency. Multiple studies have found that TRACE has improved liquidity, but only in the narrow sense of reducing trade execution costs. Market liquidity, a term often used loosely by policy makers, can mean multiple things. It may mean the degree of market “tightness,” or the cost required to execute a transaction immediately, generally measured by the spread between the offer price faced by a buyer and the bid price faced by a seller. But liquidity can also mean depth, the ability of markets to absorb large buy and sell orders with minimum impact on prices, or resiliency, the speed with which market prices recover from an unexpected order.

According to TRACE’s example, a real-time post-trade data repository for commodity OTC contracts will significantly reduce market tightness, or the average execution cost faced by a customer. This also means that market makers, who reap the spreads between bid and ask prices, will lose the economic rent they extract from less informed customers. However, there are longer-term trade-offs that must be considered. By reducing the option value of holding contracts in the prospect of closing a trade, real-time reporting disincentivizes dealers from holding inventory to execute large trades. Thus liquidity gains in reducing market tightness may be offset by losses in market depth.

Centralized Clearing

The 2008 financial crisis focused a spotlight on the interconnected web of bilateral credit relationships among the large systemically important financial institutions that helped propagate the initial shock of the failure of Lehman Brothers into a catastrophic systemwide loss of liquidity.

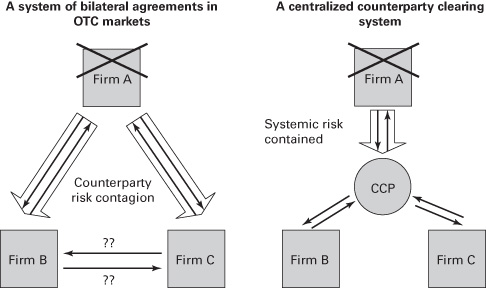

A central counterparty clearing (CCP) mechanism promises to stem financial contagion, by imposing, as the name implies, a central counterparty between the original transacting parties to guarantee execution of the transaction. Appropriately, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 emphasizes the mandatory trading of standardized OTC swaps through CCP clearing houses. Financial participants can make transactions confident that they are protected from idiosyncratic counterparty risk by the creditworthiness of the CCP. Furthermore, introducing transparency, record-keeping, and risk supervision is more logistically straightforward for a CCP clearing house than for the often dense and impenetrable records of multiple bilateral transactions.

However, a CCP clearing house requires economies of scale to be efficient, liquid, and cost-effective, and CCP clearing carries risks as well. In effect, a CCP clearing house consolidates the risks of multiple bilateral credit relationships into one giant centralized risk deposit, effectively aggregating multiple medium-sized risks into one extreme “too-big-to-fail” entity, namely, the house itself. In a system of bilateral arrangements (the left-hand side of figure 10.4), the failure of one firm (A) leads to losses for other firms (B, C) that contract with it. Contagion arises when one of the counterparties—say, firm B—begins to question firm C’s exposure to firm A’s failures and by extension, firm C’s ability to remain solvent as its counterparty to the set of bilateral agreements it has with firm C. This shroud of uncertainty leads to a rapid drying up of liquidity in markets, creating significant rollover risk for firms that are highly leveraged with short-term liabilities, particularly when they have nothing to post for margin calls. The CCP system (the right-hand side of figure 10.4) reduces this risk by bringing all parties to the table, netting exposures, and guaranteeing execution of transactions.

Figure 10.4 Contrasting risk-sharing in a system of bilateral arrangements versus a central counter-party

Theoretically, private insurance may be sufficient to manage house systemic risk, given its greater transparency and ease of quantification compared to the nontransparent bank balance sheet risks without mark-to-market procedures. But taxpayers may again be liable if a critical CCP house becomes vulnerable as a result of the failure of several of its constituent members and insurers because of other outside risks.

Furthermore, the network effects of such consolidation are still poorly understood. Preliminary studies suggest that aggregate credit risk would be reduced only when multiple different derivative classes, such as commodities, foreign exchange, and credit-default swaps, are jointly cleared in a single CCP rather than separately cleared through two or more CCPs.3 This again suggests that international coordination between regulators will be helpful to ensure that sufficient economies of scale are achieved with a minimum number of CCP clearinghouses.

However, this raises difficult questions as to whether the U.S. government, and ultimately taxpayers, would become liable if, for instance, a Europe-based CCP clearinghouse heavily used by U.S. financial institutions failed. Indeed, this is just one instance of a broader question confronting any systemically important part of the postcrisis global financial architecture: if it fails, which nation, if any, would be responsible for footing the bill of a rescue?

Beyond the issue of responsibility, would any electorate or government accept a solution that might see power or control of a systemically important financial institution ceded to a foreign or supranational entity?

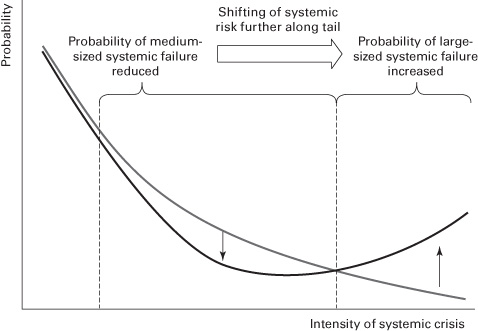

As such, the feasibility of the CCP solution goes beyond economics itself. Regulatory harmonization and cooperation between the various national regulators is indispensable to prevent a tragedy of the commons whereby each nation wishes to defer the regulatory and financial burdens of managing systemic risk to others. Figure 10.5 shows how the mandating of CCP may be shifting the probability of financial crises further along the tail, lowering the probability of moderately intense financial crises but raising the probability of very extreme ones.

Figure 10.5 Probability of transfer of systemic risk.

Capital and Margins Requirements

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, one of the immediate regulatory responses was to require banks and other financial institutions to meet more stringent capital and liquidity requirements. Certainly, regulatory capital can be a powerful tool in curbing excessive risk-taking and preventing systemic crises, and both the U.S. Federal Reserve and other financial policy-making houses use capital and margin requirements and financial stress-tests to enhance macroprudential supervision.

However, unlike transparency and centralized clearing requirements, which has promising gains in market efficiency and improved systemic risk control, the effects of capital and margin requirements on market efficiency are more ambiguous. Setting capital requirements proportionate to the amount of risk a party assumes is more an art than a science.

On one hand, in the context of OTC markets, regulators appear determined to impose stricter capital and margin requirements on non-centrally cleared derivative transactions, given the greater potential counterparty risks of bilateral relationships over a CCP. This may additionally incentivize financial participants to use more exchange-traded and CCP-cleared standardized transactions, creating the desirable economies of scale discussed earlier.

On the other hand, high capital and margin requirements might unnecessarily weaken the legitimate market for customized OTC products. The additional amount of cash or equivalent that must be posted as a collateral for margin calls might be significant enough to deter the formation of such idiosyncratic markets to begin with. For instance, a contract linked to a non-benchmark grade of jet fuel might be of great importance to jetliners but excessively stringent regulatory requirements for OTC products might destroy the market, leading to the loss of a potential hedging instrument.

In addition, it is important to note that stricter requirements may not necessarily reduce financial volatility but may even contribute to it after the fact. Again, regulators may draw lessons from the 1993 failure of Metallgesellshaft AG, a large energy wholesaler. Metallgesellshaft AG had offered long-term (five- to ten-year) contracts promising delivery of heating oil and gasoline at fixed prices to retailers, and offset these obligations through the purchases of near-term futures contracts. This risk management strategy proved unviable when the term structure of energy prices moved into contango, in which short-term prices drop below long-term prices. Putting aside the wisdom of such risk management practices in principle, the deterioration of their marked-to-market short-term futures positions triggered a cascade of margin calls that eventually led to collapse and a systemwide loss of confidence, even when Metallgesellshaft AG may have been technically solvent with its promised future cash flows.

Given the extreme volatility and the significant possibility of large swings in commodity prices relative to the prices of other financial products, overly onerous margin requirements may result in a far higher frequency of the margin calls that trigger the sorts of systemic failures that the requirements try to prevent in the first place. In other words, tighter margin requirements may reduce some risk-taking in the first place, but once a contract is written, every amount of risk taken ultimately increases the chance of a margin-call driven forced liquidation. This leaves the overall impact on systemic risk uncertain.

Position Limits and Hedge Exemptions

If there is legitimate concern about whether higher capital and margin requirements can ultimately improve market efficiency, the author finds the efficacy of position limits even more ambiguous. Politicians have found something timelessly appealing in the idea that somehow manually capping the presence of speculators can prevent the next bubble and reduce market volatility. Not only does this ignore the gaping shortfalls in physical and financial transparency that may better address market volatility, it also ignores the irreversible growth of financial derivatives linked to commodities. Binding position limits will likely be counterproductive in restraining excessive speculation and may be useful only for the narrower purpose of preventing market manipulation. There are several reasons why position limits or hedging exemptions have limited effect on reining in excessive speculative behavior.

First of all, enforcing position limits will draw regulatory resources away from other responsibilities and add cumbersome regulatory regimes to the often ill-defined boundaries between exempt commercial hedging and speculative risk taking. Enforcement is further hampered by the fact that market participants will still be able to create alternative offshore investor entities and vehicles in other financial centers such as Dubai, Shanghai, or Singapore. Given the logistic challenges of enforcing tight position limits, regulators would be better advised to first address shortfalls in physical and financial transparency before turning to more radical interventions.

In the United States., the Commodity Exchanges Act grants the CFTC the authority to impose limits on the size of speculative positions in the futures market. Today, twenty-eight key commodities or “Core Referenced Futures Contracts,” ranging from agricultural contracts to the four energy contracts on NYMEX are subjected to set of position limits depending on whether the contract is within the month of delivery and without (“spot month” vs. “non-spot month”). Although spot-month limits have been around prior to the Dodd-Frank legislation, the newly added non-spot month was subjected to greater public scrutiny.

In recognition that there is a genuine need for hedging by commercial entities, the CFTC also grant exemptions to bona fide commercial hedgers with physical exposure and swaps dealers qualifying under a newly created financial “risk management” exemption. While commercial hedgers are permitted to take up positions of unlimited size, swap dealers only receive a “partial exemption” as limited to two times the position limit (on a single-month or all-months-combined basis). Although the CFTC has rightly declined to offer exemptions to index funds and ETFs, the regulation has had an unintended effect of pushing fund managers to turn to OTC swaps to meet their new position limits, effectively transferring risk from one segment of the financial market to another, since investors in these funds now face counterparty risks.

Conclusion

The preceding sections have highlighted the need for measured caution and sensitivity when regulating commodity financial markets. Commodity prices will unavoidably continue to fluctuate intensely given fundamentally low elasticities of demand and supply, making full price management impossible. The key is to recognize the fact that there is natural volatility in commodity markets due to imperfect information. As such, policymakers should not be obsessed with stamping out on all speculative behavior, but rather design policies that reduce unnecessary market volatility and align market prices closer to fair valuations. Both blanket hostility toward speculative activity and unbridled faith in deregulated markets preclude intelligent efforts to improve markets.