When my mother was twelve, she went to visit her father. My grandfather Roman had left my grandmother Helen a second time, for good, after my mother was born. My mother and her family stayed in Chicago while Roman moved to the suburbs with his new wife, Josephine.

My mother didn’t tell anyone she was going. There was nowhere she was expected to be after school; no one would worry or wonder where she was unless she missed dinner. She was fluent enough in public transportation that she could get herself into the suburbs by bus and find his home, though she’d never been to it.

Like every other house on the block, her father’s had a narrow patch of lawn. She rang the bell and waited.

Roman opened the front door.

“Hi, Dad!” she said. She spoke with an announcer’s boom and cheer to play up the surprise.

His tight face went slack when he saw her. Before he could say anything, Josephine came up behind him in a dress from a nice store.

My mother said, “Hello, Josephine.”

Josephine nodded, whispered in her husband’s ear, and disappeared. Roman brought his face to the screen. “You can’t be here.”

My mother held his gaze.

“We have company, and they don’t know about you. You have to go.” He didn’t wait for her to respond. He shut the door, trusting she would leave.

She did.

My mother needed to tell this story at least once a year. “My own father!” she’d rage to me, my sister, whoever her audience was that time. “His own daughter!”

I met Roman and Josephine only once, when I was about ten. My mother and I and were visiting Aunt Arlene, who then lived in the Chicago suburbs, during the summer. Arlene had managed to create some sort of relationship with Roman and he knew my older cousins, though not well. My mom didn’t ask me if I wanted to meet him, she just told me I was going to one morning as I ate breakfast. I slumped in my chair. “I don’t want to.”

“You have to,” she said coolly. “They’re picking you up this afternoon.”

“Are you coming?”

She took a small sip of coffee, then shook her head.

“Why do I have to meet him?” I wanted to hang out with my teenage cousin Susie, play in the backyard, read, do anything else. I pushed my cereal bowl away.

“Because it’s important,” she said, and nudged the bowl back. Perhaps she’d surprised him by insisting that we meet. As she had when she was young, she was forcing him to acknowledge her, and her daughter as well.

My mother and I waited for Roman and Josephine in front of Arlene’s house. Tension locked her body when they arrived, and it rushed into mine as her hand gripped my shoulder. She greeted them from her position on the stoop, then shoved me toward their car.

Roman was small and grumbly, Josephine pretty and polite. As he drove, Roman asked me short questions about school. I gave him short answers. I was good at talking to adults and knew I was supposed to ask them questions as well, but even basic conversation seemed dangerous. What was I supposed to know or not know? How could I trust any of his answers? I knew it was important to my mother that I be there, though I wasn’t sure why, but also sensed that I wasn’t supposed to like him. Instead of asking about the wrong thing, or saying something bad, I tried to look fascinated by whatever was on the other side of the window.

They took me to Santa Land, a small Christmas-themed amusement park that blared carols even in summer. Every time we approached a ride, Roman asked if I wanted to go on it, and I said yes, even the ones for little kids. “If I go on them all,” I thought, “we’ll have to leave.” I rode alone as he and Josephine watched with stilted grins. He tried to buy me a snowflake T-shirt, a stuffed elf, and ice cream, but I wouldn’t let him.

When we pulled up in front of my aunt’s house at the end of the day, I said “Thank you” and leaped out of the car. My mother opened the door for me and waved quickly in their direction.

“How was it?” she asked as I kicked off my sneakers.

“Boring,” I shouted, then went to the kitchen to look for snacks.

My mother learned of Roman’s death in 1998 through her cousin Chrissy, who saw his obituary in a local Chicago paper. She mailed it to my mother, and I was home from college when she received it. She read it on the couch as I sat next to her, then crumpled it in a ball and tossed it on the carpet. “It says he’s survived by his wife Josephine and his stepdaughter, Teresa. No one bothered to mention me or Arlene, his real daughters.”

“Well,” I ventured, “that’s not really a shock, is it?”

Anger fixed her face, then a ripple of heartache disturbed it. She swiped a cigarette from a crumpled pack, lit up, and took a drag. After a long exhale, she sniffed. “What an asshole.”

I put my hand on her knee. She kept her gaze on the far wall, then she stood with a jerk and said she needed a nap.

I looked up Roman’s obituary, thinking it might reveal something about the man who had betrayed my mother and her family, while preparing to visit Chicago. It was cursory and brief—a list, not a life. The only helpful information it offered was the full name of Josephine’s daughter, Teresa. A quick search revealed that she was still alive and living in Chicago. I wanted to know more about Roman, his illness, and his life with his second family, so I wrote her a letter explaining who I was and what I was hoping to learn, and sent a copy to the two different addresses I found online. With enough warning and explanation, I thought she might be willing to meet me while I was there.

As I had with Aunt Lana, I’d called Aunt Arlene and Chrissy and told them I wanted to know more about my mother. Arlene told me she’d be visiting Chrissy in a few weeks; they both suggested I join them in Chicago. I was relieved they were open to having me monopolize the time they’d planned to spend with each other.

Chrissy lived in a large suburban house that reminded me a bit of my parents’ because it was filled with Asian art and fancy rugs. When I pulled up in front of it, Chrissy and Arlene bounced out to greet me with squeals, and we hugged eagerly.

I hadn’t seen either of them since my mother’s funeral four years before.

I’d always known them to be cheerful and fun. They were constantly teasing each other and cackling so hard that they ended up gasping for air.

The three of us spent days in Chrissy’s small kitchen, draining bottles of white wine, looking at pictures, swapping stories and theories about my mother, talking over one another, making long digressions, and jumping between topics as I grilled them for details about my mother’s life.

My mother’s family lived on Chicago’s west side in a predominantly Polish neighborhood populated by factory workers and plumbers. Their small two-bedroom apartment was above a drugstore and across from a bakery where Arlene and my mother bought strawberry-filled paczki on Saturdays.

Arlene was three and a half years older than my mother, and Chrissy was a year younger. Chrissy and her older brother lived in a nicer part of town, but Chrissy always begged to stay with her cousins because she wanted to be with the girls. The three of them often spent summer days at Riverview Park and North Avenue Beach, or playing in alleys.

When I was a child, my mother frequently reminded me that she grew up very poor. Arlene and Chrissy confirmed that. “My family didn’t have much,” Chrissy said, “but your mother and aunt? They had nothing.” They would never have been rich, but they had “nothing” because my grandmother was a single mom and worked a menial job at a candy factory.

Helen and Roman were introduced by my great-uncle Eugene, who knew Roman from high school. Eugene was seeing my grandmother’s younger sister, Genevieve, and he set up Helen with his friend in the hopes of increasing the chances of his own dates being sanctioned. Helen and Roman married after a year of dating.

Roman had gone to welding school, but he hated welding and working in general. Arlene believed he may have left his job while my grandmother was pregnant with her and was still looking for work when she was born in 1941.

After Arlene was born, Roman went into a manic state and bought a lot of things the family didn’t need and couldn’t afford. “I don’t know how you could buy things on credit in those days,” Arlene said, “but he supposedly bought six suits, an organ, and a boat—”

Chrissy interrupted. “I heard he went out to buy a new refrigerator, because he and Helen were living in this small place and had a little tiny refrigerator. He wanted a bigger one for his growing family.”

“Fine, he bought a boat and a refrigerator.”

“No.” Chrissy giggled. “He left to buy a refrigerator but he came back with a boat.”

When Roman’s behavior didn’t normalize, Helen had him involuntarily committed. He was institutionalized for somewhere between nine months to a year and a half. He never shared his diagnosis, but Arlene’s guess was that he was bipolar, though that term didn’t exist at the time.

I asked Arlene if he’d displayed similar behavior before she was born. She said she didn’t think so, but her mom told her that she knew my grandfather was unhappy when she first met him, and she hoped she could change that by marrying him.

“Oh God!” Chrissy sighed. “Don’t women always think that?”

Roman’s mother went behind Helen’s back and had him released, and he stayed with his parents for a while. “My mom didn’t know where he was for a long time, but one day, he showed up,” Arlene explained. “And she took him back! Then she got pregnant with your mom. I don’t know if he got a job then or what. Maybe there was something with Western Union. Then your mom was born, and he left the next day.”

Chrissy leaned toward me. “I don’t know if you know this. Your mom was a breech baby. The doctor had to break her clavicle in order to extract her from the birth canal. She was in intensive care forever. Even after Helen brought her home, your mother was so fragile that she couldn’t be held for several months.”

“I didn’t know that,” I said, then I paused. “Did I? I don’t think so.” That seemed like the exact kind of story my mother would have loved to tell. She’d been a victim from the start, a broken baby immediately abandoned by her father. What life could she build on such a faulty foundation? The only reason I could come up with for why she hadn’t told me about her birth was that its difficulty reminded her of Yuri.

I thought of her arriving into the world in a state of animal pain, needing so much comfort and only receiving the lightest strokes from my grandmother’s fingers. It could have had lasting effects on her personality. Babies who aren’t touched often struggle to form attachments, empathize with others, and regulate their emotions.

When Roman left, my great-grandmother, whom Arlene and my mother called Buscha, moved in so she could supplement their income with her Social Security. She was a worn-down woman who took pleasure in wearing down others. She spoke enough English to complain to butchers and give orders, but she preferred going after people in gruff Polish. She and Helen worked at the same candy factory; Buscha worked the day shift while Helen worked at night. When Buscha arrived, she claimed one bedroom for herself, so my mom and Arlene moved into Helen’s room. Arlene slept on a thin cot with squeaking springs, and my mother shared Helen’s bed until she was fifteen.

“Fifteen?”

“Oh yeah. She didn’t get her own bed until I went to college, and even then, they still shared a bedroom.”

When I thought of having to share my bed with my mother, my skin got sticky. I would have considered it an intrusion, even as a small child. But my mom may have found the warmth of her mother’s body comforting. My mother and grandmother always had been very close; perhaps sharing a bed for so long was one of the reasons why. When Helen died in 2005, my mother pulled her darkness even closer. Her mother died because she was old; at the time, I didn’t get why it was so devastating, but learning this made me see my mother’s reaction differently.

Helen had dropped out of high school after tenth grade so she could help support her parents, but she was determined that her daughters would be well educated. She monitored their performance in school and expected them to go to college. She saved money in order to pay for ballet and Polish dance classes, and for horseback riding lessons in Lincoln Park. Though she worked five night shifts in a row, she took her daughters on long bus rides on weekends so they could visit art museums downtown.

“We never just sat home,” Arlene said. “And Anita and I wanted to! Do you know how long it took for us to get to the Museum of Science and Industry without a car? We had to stand in the heat or the cold waiting for the El…Once we got wherever we were going, we had a great time, but we always put up a fight.”

My mother might not have wanted to go to museums, but, Arlene told me, “she always wanted to be out and doing things. Your mom was always goofing off, telling stories, making jokes. We walked up and down streets, played kick the can, roly-poly, and hide-and-seek in the alley with whatever other kids were around. We’d be out all day. There was no adult supervision.”

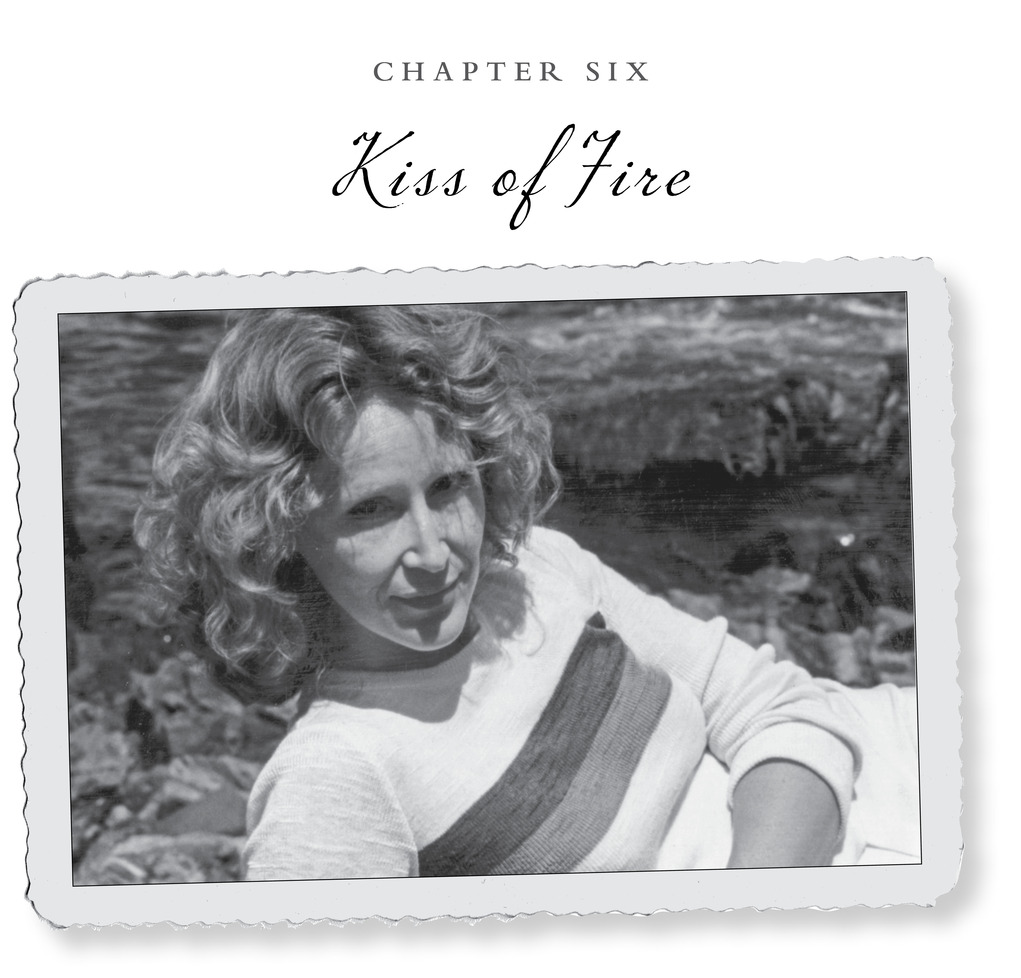

“Your mother was such a cutie,” Chrissy added. “I remember her running around in these silky magenta shorts that my mom made for her—not for me, mind you—with her curly blond hair, and thinking, ‘Wow, I wish I had her shorts, I wish I had her curly blond hair.’ ”

Sunday was the only day both Helen and Buscha had off, and it was the one night that the four of them ate together. “Every Sunday,” Arlene said, “we ate together, and every Sunday we had a family argument.” Buscha would cook pot roast with gravy or sausage and potatoes, and she’d have a glass or two of wine while she cooked, and a few more during dinner. “Meals started off okay, but after some wine, Buscha’s mind just went pshh. She’d say all kinds of critical things about our mom to her face, and my mother would get weepy. I’d get upset and defend her. ‘Don’t talk to my mom like that, that’s not nice!’ But it didn’t make a difference.” Buscha was relentless, and she used Arlene’s protests as fuel, telling Helen, “Look at how your kids behave. No wonder your husband left you,” which caused Helen to cry even harder.

Sometimes Buscha hosted a little party on Sunday instead of a miserable dinner. She invited friends of her husband’s and her cousins, Helen and Arlene’s uncles. They played bridge and rummy, complained about their bosses, and wondered if the Italians were moving in.

Company meant my mother and aunt could wear the frilly dresses their mother had made for them by hand. My mother was a ham, dancing until she got applause, practicing card tricks, and reciting the ads for toothpaste that played on their radio when it wasn’t broken.

One of their great-uncles, the husband of Buscha’s dead sister, always asked my mother to sit on his lap. She did, and as he’d stayed in whatever conversation or card game was happening, he slowly worked a hand between her thighs and into her underwear.

Arlene didn’t know what was occurring; my mother didn’t tell her about the molestation until decades later. She said the abuse never went any further, and that she didn’t even understand that it was abuse for years. Arlene confronted my grandmother about it, and my grandmother said she’d never had any inkling that was happening. My mother never told her, neither as a child nor as an adult.

My mouth went bitter as I considered that my mother, fizzing with excitement and eager for attention because it felt like love, had been molested repeatedly in front of people who should have protected her. There really was no supervision, even when adults were around. Arlene kept talking, telling me that my mother had never seemed scared of this man—they’d both adored him. When he put on his coat at the end of the night, my mother would beg him to stay.

It was hard to hear this. My mother could have hated what was happening but felt she couldn’t stop it. Or perhaps this man’s caresses made her feel special. Maybe any male attention felt like love and could briefly fill the space left by her father.

As a child, I would have been scared and repulsed if I’d heard this story. Like when I’d learned about Yuri, I would have been overwhelmed to know how much pain my mother had endured and afraid of how her turmoil threatened my safety. Hearing about these incidents decades after they’d happened, and after witnessing what my mother did to herself, I went cold. I had to force myself out of fantasies where I appeared in my mother’s childhood kitchen in my clothes from the future and violently swept her off of that man’s lap, and him out of her life and family. I felt sick and complicit for not having stopped him. As I sat there, I understood that my mother had kept some stories to herself, ones that she should have shared with someone. Being abused, and not speaking about that abuse, could have taught her that her pain and body didn’t matter, and been yet another factor that would later lead her to alcoholism.

My mother told me so little about Roman that I’d always assumed he was completely absent from her life, but Arlene said that he took her and my mother out on occasional Fridays. I was surprised that he felt even that much duty to the daughters he’d discarded.

“We would meet him on the corner, he didn’t come to the door. We’d have to go half a block, stand on the corner. We could have been kidnapped! Your mother didn’t like it as much as I did. I had fun; I was happy to see him. He took us to little amusement parks or to the circus. If I wanted cotton candy, I would get cotton candy. If I wanted a turtle, he’d buy it for me. Anita stopped going after a while, I don’t know why, but I kept going.” Arlene said that he didn’t seem mentally ill or “off,” but he was quiet.

My mother’s decision to stop joining them struck me as a pointed refusal to recognize Roman’s paltry effort. Occasional afternoons or evenings didn’t make up for his disappearance, and she didn’t want him to believe that they did.

He gave Helen money when he could, but it wasn’t enough. When Arlene was eleven and my mother was eight, Helen consulted a lawyer about receiving child support. The lawyer returned with good news and a big question. Yes, Roman was working and could pay child support. But was she aware that he’d married someone else?

She wasn’t. She barely spoke to him. Even though she was angry and embarrassed that Roman had left her, she hadn’t divorced him because she didn’t want to be excommunicated from the Catholic Church. That was also why she’d never remarried, though she’d had boyfriends who’d expressed interest. But when she learned Roman was married, she had to divorce him. Arlene wasn’t sure when he’d remarried, but thought he may have met Josephine during one of his hospitalizations. She remembered hearing that Josephine may have also dealt with mental illness, perhaps in the aftermath of her first husband’s death.

“When your mom found out about Josephine, was that when Josephine found out about her and you guys? And that he’d never bothered getting divorced?”

Arlene took a sip of wine and said she had no idea.

He told Josephine at some point, and the way my mother told the story of her surprise visit made it sound like she’d met Josephine before. But he was still hiding his first family from most of the world, and my mother would have become even angrier with him than she had been; he’d been haplessly playing father while living a secret life.

Arlene didn’t know why my mother stopped joining the excursions with their father, but she thought that my mother was brave because when she decided she did want to see him, she sought him out.

I told her I knew the story of my mother showing up at Roman’s. “She was brave,” I said. “It took a lot of guts to go there alone. It was a kind of ‘Fuck you.’ ”

Why had she gone to see him that day? To remind him of her existence, of his mistakes and choices? Did she hope that he’d invite her in, and they’d spend a nice afternoon together? She may have wanted his love, but according to Arlene, my mother wasn’t interested in forgiving him. If she’d wanted to needle him, she would have at least succeeded in making him uncomfortable. But that was undercut by his rejection, his literal denial.

Teresa never contacted me, so I reached out to her again after I’d been in Chicago for a few days. I didn’t want to call her; I wanted her to call me, to want to talk. I wrote two short notes and delivered them to the addresses I had. Both were in humble neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city. At the first, the current resident informed me that Teresa hadn’t lived there for years, but that he’d received my original letter and given it to her cousin. At the second, I slipped the note into the mailbox mounted next to the door.

On my way back to Chrissy’s, I stopped by a supermarket to pick up flowers and wine. When I got back into my car, I turned it on and found I didn’t have the strength to drive the few remaining miles to her house. I turned the car off, pushed the seat back, and stared at the roof.

There’d been so much noise all week. Every day I had absorbed more and more information. Sadness whirred beneath every discussion, and my mother was the center of each, even the ones that weren’t about her. When I wasn’t talking with Chrissy and Arlene, I was replaying our conversations as I drank in the kitchen while everyone else slept, or in my dreams when they came. My mind was always finding or making connections between stories, coloring them in and extending them. What had stopped me was the car’s intense silence, so loud that it stung my ears and made me notice they were raw, and that the rest of me was, too. I was wrung out but still wet, yet I couldn’t go completely limp. I had more interviews, more people to see and conversations to carry with humor and graciousness. I groaned as I sat up and started the car again, thinking about what Arlene had told me the other day.

My mother was a natural performer and loved embarrassing Arlene in public. Sometimes when they were riding the bus, my mother would cause a scene as a joke. She called her sister “Hortence Anastasia Waskavinska,” and when the bus was crowded, she’d loudly exclaim, “Oh Hortence, will you behave yourself?” or “Hortence Anastasia Waskavinska, what’s wrong with you?” while Arlene held her bag in front of her red face.

My mother’s mischievousness and spirit had one particularly infamous display. At her school’s end-of-year picnic, when she was in the fourth grade and Arlene was a seventh grader, my mother ran onto the makeshift stage at the end of the talent show and broke into a rendition of Georgia Gibbs’s 1952 recording of “Kiss of Fire.” She rocked her hips and tossed her hair, giving her best impression of a femme fatale, and crooned about being a “slave” to “devil lips” in front of a scandalized audience of nuns and children.

“I was so embarrassed,” Arlene told me. “But even then, I was impressed by her stage presence. It was really incredible.”

“Did the nuns call your mom?”

“Not that time, but other times. They threatened to kick Anita out of school.”

“Kicked out!” I cried. “Why?”

“She was caught passing notes to a boy. I don’t know if he wrote it or she did, but it said, ‘If you want to kiss, I will.’ ”

I laughed. “I did stuff like that at the same age. I think that’s pretty normal.”

“Not in Catholic school!”

“Your mom always had a way with men,” Chrissy said. “Whenever we went to a dance, she got the good-looking guy immediately. She never had any trouble attracting them. She was a big flirt, but she wasn’t obvious about it. She just had a way about her, smart and vulnerable at the same time. I think a lot of guys found that very appealing.” She spoke of witnessing my mother flirting with men and having them “wrapped around her finger” in minutes. I’d seen similar things as a child, my mother receiving extra attention, men lingering in her presence, and sensed there was something different and charged in those interactions.

“I’m a big flirt, too,” I admitted.

Arlene and Chrissy feigned shock. “No, you?”

“I can’t help it!” I laughed. “I flirt with everyone. I always thought it was my personality, but maybe I do it because I watched it work for my mother.” I’d never considered this before, but it made sense. Flirting with people made basic interactions more fun. The attention was validating, probably more than it should have been, and whomever I flirted with generally seemed happy to participate. My behavior only caused problems if someone took it to mean that I was more interested in him than I was, or when I was dating a guy who was insecure.

While I was in Chicago, I also visited my mother’s best friend, Sylvia. We chatted on her balcony, smoked her thin cigarettes, and drank instant iced tea. Sylvia had been a constant presence during my childhood. Every time we went to Chicago to visit my grandmother, we’d see Sylvia as well—she’d stayed in the city and had a family—and she would also visit us in Boston. She and my mother talked often on the phone and quickly regressed at the sound of each other’s voice, giggling and gossiping and making squeaky kissing noises into the receiver. Though they were grown-ups, theirs was the kind of friendship I’d always wanted to emulate when I was a child: intimate, necessary, and exalted. Despite my problems in middle and high school, I’d been able to cultivate and maintain friendships that were far stronger than the ones I had with my relatives. I often put more into my friendships than my romantic relationships because I found those alliances more rewarding and permanent. I’d loved few partners as deeply as I loved my friends.

At my mother’s funeral, Sylvia handed me a stack of letters and postcards that my mother sent her over their five-decade friendship and said, “These are yours now.” In these letters, my mother confessed her deepest secrets and fears, details of her life both exciting and mundane, and gushed about her love for her friend. In 1973, almost twenty years after they’d met, my mother wrote Sylvia from London and explained, for possibly the thousandth time, how special she thought she was. “How do I love thee, let me count the ways…I’ve made several friends since I have been here but none will ever be as precious as you. Really, truly, you are a comfort, an excitement, a lasting you. I feel happy whenever I think of you.”

I asked her to tell me again the story of how she and my mother became friends. They were in the same first-grade class at the local Catholic school. There were around sixty kids in one room, and at first they didn’t know each other. “Your mother was a talker.” Sylvia laughed. “Me, I was quiet. I didn’t dare step out of line. Finally, the nun had had it with your mother and said, ‘Change your seat and sit next to Sylvia. Maybe she’ll teach you to be quiet.’ So we sat next to each other. Your mother still wasn’t quiet. That’s how it all started.”

My mother’s father was absent; Sylvia’s had died. “We had that as a bond from the very beginning,” Sylvia explained. Her mother remarried and had more children with her stepfather. Once she and my mother became friends, they spent their afternoons together because Sylvia didn’t like being at home. After school, they’d walk to my mom’s apartment so she could drop off her bag and they could play. After a few hours, my mother walked Sylvia halfway home as they held hands and then parted with a hug.

Sylvia told me that when they became friends, she began praying every night for the opportunity to sleep over at my mother’s house before she died. She demonstrated, placing her hands together and looking up. “ ‘Please God, don’t let me die until I get to sleep over at Anita’s.’ And I did pretty soon after that. We slept with your grandmother in that one full-size bed. I slept over lots of times after that. I became a part of the family. Helen was so sweet. She was so good to me.”

We both smiled at her memory. “My mother was always really sweet to my friends as well,” I said. “She really encouraged my friendships when I was young, made sure I had sleepovers and got to spend time with the kids I was close to.”

Sylvia and my mother had more in common than missing fathers. Both were Polish, short, and had curly blond hair. “We were twins,” Sylvia said. “We did everything together. We had to do everything the same.”

Wanting to have everything that the other had became a problem when it was time for their first communion. Sylvia’s family had more money, and her mother bought her a beautiful dress. When my mother saw it, she realized the one Helen had bought her wasn’t nearly as nice. So she begged and pleaded and ranted and raved until Helen gave in and bought her the same dress.

Hundreds of children were receiving their first communion on that day because the bishop was in town. My mother and Sylvia made sure they sat together so when they went up to the communion rail, they could be next to each other. A cloth was laid over the rail so the children wouldn’t be tempted to touch the Eucharist. As Sylvia and my mom stuck their tongues out for the bishop, they put their hands together under the cloth and linked pinkies.

“That’s adorable,” I said.

“It was, but we were hardly angels. We were very unsupervised growing up, so we found lots of time to get into trouble. Your mother was an instigator; she had a lot of courage. The trouble that I got in, I got into because of her.” Her smiled puckered around her cigarette. “We started smoking in third or fourth grade; that was all your mom.”

“She always said that you were the one who got her smoking!”

“Me? I would never have had the nerve!”

One of Sylvia’s favorite stories was about their prom. They’d double-dated, worn puffy dresses and tiaras. After the dance, the couples went out to dinner, per tradition. “Your mom and I had the brilliant idea of switching outfits. So we went into the bathroom, switched dresses, and came out. We thought it was the funniest thing in the world, we got such a kick out of it. Our dates were not amused.”

They’d always intended to go to college. “We both had wanderlust,” Sylvia said. “We wanted adventure. That was one of the good things about both of us coming from humble backgrounds. We were always striving for more, and we wanted to travel more than anything else. Your mom traveled a lot more than I did, though. I was a little jealous, I think, but I was happy for her.”

“Did she talk to you about my father’s decision to work in Ukraine? Was she angry that he made that choice and went somewhere for so long without her?”

“She did. She resented Ukraine because he felt closer to Ukrainians than he did to his own family. And I think a lot of that was just loneliness, and being with a kid who was out of control.” She gave me a tight smile and I hung my head.

I thought of how I treated my mother when I was in high school. I hit her and I held a knife on her, and she’d just taken it. I spoke quietly. “Did she complain about me?”

“I wouldn’t say complained, but she was frustrated. She just didn’t know what to do with you.”

“When I think of how I behaved as a teenager, I feel terrible. I gave her hell.” I sighed. “I feel so guilty for everything I put my mom through when she was already going through so much.”

“Good!” She laughed. “Kids should feel guilty about stuff like that.” When I winced, she quickly added, “But you know, you can’t be too harsh on yourself—that’s part of growing up. Adolescence is an awful time; you say and do terrible things. So you can’t…you can’t punish yourself.”

“Well, I do,” I told her. “I feel a thousand times worse about what I did now than I did then.”

When I was leaving, she took my hand. “There was a lot to your mom. She had so many positive things going for her, but she had her demons. She did the best that she could, so there’s no blaming her, there’s no thinking less of her. She was human.”

“I spent a long time blaming her for the problems I had with my father,” I said, “struggles I had as a young adult, for her drinking. But I don’t want to. Not anymore.”

We hugged. She was smaller than my mother, and skinnier than my mom had been at the end. When we held each other, I felt that we were holding my mother between us.

“I hope I don’t cry when you leave.” Sylvia’s eyes were already full of tears. “I lost her so many years before I really lost her. It’s such a big, big sadness.”

The next morning, as I was getting ready to drive out to the second address I had for Teresa, I decided to call her first. If a machine picked up, I wouldn’t leave a message. If she picked up, I’d hang up and jump in my car.

After a few rings, a woman answered. I froze, then started speaking without meaning to.

“Is this Teresa?”

“It is.” Her voice was thin and testy.

“This is Anya Yurchyshyn,” I said. “I’m the woman—”

She cut me off in a voice far stronger than she’d answered with. “I got your letters. I didn’t respond on purpose. It was embarrassing to have that letter forwarded by that other family because that was from forty-five years ago.”

“I didn’t mean to upset you. I just want to ask—”

“I don’t want to be a part of this! It’s in the past. I have enough grief.”

I knew that conversation was probably the only one I’d have with her; my sympathy was overridden by my desire to know what had happened. I rushed to appeal to her. “There has been a lot of grief in my life as well, as there was in my mother’s life, and I’m just trying to understand what happened—what Roman was like as a father, and if you knew that he had children from another marriage.”

She said, “I’m not ready for this,” but continued anyway, speaking in fragments that were difficult to connect. “Roman was very secretive. He was hiding a lot of things. Roman never spoke to me about having other children. That was one of the things that bothered me.”

“So he didn’t tell you about his other children? Who did? Your mother?”

“We always had his family over for dinner on Sundays and no one said anything.”

“That must have been so upsetting.”

“My mother went into a terrible depression.”

“After she found out?”

“I didn’t find out until my mother went into her postmenopausal depression.”

“So your mother hid this information from you, or do you think she didn’t know, either, and finding out—”

“I had a lot on my plate having them sick for a long time.”

“You took care of them? That must have been very difficult.”

“It was! Of course it was. I wish someone would ask if I needed something instead of always asking if they could have something from me.”

“Is there anything I can do for you, Teresa?” I stuttered. “I would love to help in some way.”

“Just leave me alone.”

I couldn’t make much sense of what she’d told me, all I knew for sure was Roman eventually caused his second family as much pain as his first.

I spent a few more days speaking with some of my parents’ roommates, walking around my mother’s old neighborhood and the University of Chicago campus with her friend Chip, then ended the trip with my friends Chris and Meredith. Meredith, a midwife, was working an overnight shift when I arrived.

Chris was one of my most important friends. I spoke to plenty of people more than I spoke to him, but I spoke to few people as eagerly. Sometimes we avoided calling each other because we knew we’d talk for hours. When he still lived in New York, he’d often bring a list of things we needed to discuss to whatever bar or restaurant we met at. We never got through it. Once, we both admitted that we didn’t know how we’d felt about something until we discussed it with each other. We enjoyed sharing the new developments of our lives as much as discussing events from the past, revisiting favorite stories about awkward parties and weirdos we’d dated until events from each other’s history became part of our own. As we launched into this familiar pattern, I realized we were mimicking my mother’s behavior that I’d so often complained about. Telling and retelling stories we knew by heart. I did it because it felt so good. It reaffirmed my bonds with people, explained what we had and where we’d been. But my mother’s were most often sad. She’d been touching a wound to remind herself who she was.

I told him everything I’d learned—my mother’s traumatic birth, her molestation—as he doted on me, serving me braised pork and custom cocktails. I explained that I was starting to understand the neediness I’d observed in her when I was a child. My grandmother’s devotion wasn’t enough. Roman’s flight left a cavity that couldn’t be filled by other people’s love or traveling the globe. I was still dealing with issues from my own childhood; hers must have haunted her as well. But I hadn’t ever understood that; being my mom meant she was supposed to be perfect.

I was more affected by hearing her stories from other people than I’d ever been by her own telling, and by the ones she’d never shared with me. Without her insistence that I view her as a victim, I could see her as a person who’d experienced an enormous amount of loss and be furious at myself for not being sympathetic when she needed me to be.

Chris told me that he and Meredith were going away for the weekend, and I asked if I could stay at their house while they were gone. I was driving to Minnesota in a few days, and when Chris said yes, I lied to Chrissy and Arlene and told them I was leaving early. By this point, I couldn’t handle more stories or sorrow. I wanted to be alone, enclosed by silence.

I’d been filled up with so much information but felt empty, pressed flat and thin by a weight bearing down on my body. I padded through Chris and Meredith’s house, foraged for food in the fridge, popped Klonopin, watched hours of Netflix, and poured myself drink after drink.

My last night, I saw I was dirty and disheveled; I looked like my mother. Her pain hurt me so much that I’d needed to turn the world, and my brain, off. For so long, I’d considered her weak, but simply hearing of her burdens and horrors had caused me to take to bed for days and drunkenly hope that tomorrow wouldn’t come.