Warning about False Teaching (4:1–5)

Paul follows up his teaching on the qualifications of church officers in chapter 3 with specific warnings about false doctrine “in later times” (4:1), which Timothy himself will encounter since the whole era between the first and second coming of Christ is the “last hour” (1 John 2:18). Paul ends this chapter with some positive instructions for Timothy’s public ministry (1 Tim. 4:6–16).

Things taught by demons (4:1). Paul is not concerned here with paganism per se, but with false teaching within the church. These false teachers have “abandoned the faith” they once embraced in order to follow demonic doctrines. The word “demon” (Gk. daimonion; plural daimonia) to ancient ears would not necessarily sound evil. Indeed, the pagan Greeks used to pour out a libation of wine to Agathos Daemon (“Good Demon”), who was, interestingly, represented in works of art by a snake. And Paul’s original readers were accustomed to hearing about daimonia teaching and guiding people through oracles, prophecy, or in other ways. For instance, it was generally thought that the prophetic god Apollo used daimonia as agents for the oracles at Delphi on mainland Greece or at Didyma in Asia Minor. Socrates, the famous philosopher, claimed to be personally guided by such a daimonion, leading to ancient speculation on the identity of this being.39 In contrast, Paul says that the Holy Spirit himself has expressly provided a warning against the teaching of daimonia, which are deceiving spirits (see also 1 John 4:1–3).

Whose consciences have been seared (4:2). Apostate teachers can wantonly betray their Lord because their “consciences have been seared as with a hot iron.” This arresting analogy is clear in any culture, but it was particularly vivid in antiquity where penal branding took place. An inscription found in the vicinity of Ephesus threatens branding (possibly on the foot) as punishment for seditious bakers who had been instigating local riots (IvE 215). Closer to Paul’s image, runaway slaves who were recaptured might have their foreheads branded by harsh masters (Apuleius, Golden Ass 9; 3 Macc. 2:29).40

They forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods (4:3). The apostle identifies asceticism as the particular subject that characterizes the teaching of liars. Paul was no gourmand objecting to the disapproval of delicacies. His argument strikes against the substitution of Christianity’s true focal point of “love, which comes from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith” (1:5) with an empty ascetic exhibitionism (Col. 2:20–23). The rejection of monogamous marriage was not common among ancient peoples. Both the Greeks and Romans had high ideals of marriage, particularly for the purpose of childbearing and securing the family line.

For everything God created is good (4:4). Paul alludes to his rationale for holding foods and marriage in high esteem by referring to God’s creation of these good things. After making the produce of sea and land God saw that it was “good” and later that all his creation, including the union of Adam with Eve, was “very good” (Gen. 1:20–21, 31). The ascetics do not sin against the gifts themselves, but against the Giver of every good and perfect gift (James 1:17) by contradicting and disbelieving his Word. Ambrosiaster, the name given to an unknown church father, wrote: “Why, then, do some people call that which God has blessed a sordid and contaminated work, unless because they themselves in some way raise their hands against God? For they would not criticize this [work], unless they had wicked ideas about God, the Maker of the work.”41 That God’s good provisions in creation are not “to be rejected” but to be received with thanksgiving (1 Tim. 4:4) finds an interesting verbal parallel in Homer’s Iliad, the closest thing to the Bible among the ancient Greeks: “The glorious gifts of the gods are never to be rejected.”42

Training in Godliness (4:6–10)

The importance of the objective “truths of the faith and of the good teaching” must not be overlooked. (The word “teaching” or “doctrine” occurs four times in this chapter alone.) Timothy will be a “good minister” or servant of Christ if he conveys these things faithfully. But the reward for his faithfulness for himself and others is to be “brought up” on these things, or better, nourished by these things. Pure teaching of Christian doctrine, rather than being deadening for our spiritual life, is food for the soul.43

In stark contrast to the excellent doctrine stands the degrading myths of Timothy’s contemporaries (cf. 1 Tim. 1:3–4). Rape, adultery, murder, lying, deceit, and trickery of every sort pervade the activities of the gods in ancient mythology. Many pagans thought that there might be an historical core to the myths, but that the poets and playwrights had added many embarrassing embellishments:44 “The poets tell many lies” was a common ancient saying. Plato rather disdainfully rejected such myths from the educational program in his ideal republic.45

Physical training is of some value (4:8). “Physical training” would be familiar to Timothy. The Greek word for “training” is gymnasia and is the source of our “gymnasium.” There was no institution more characteristic of Hellenic culture than the gymnasium, where youths in schools were subjected to a rigorous course of athletics.46 In earlier times, the gymnasium was essential for military training, since a city-state’s army consisted of all male citizens. By NT times, a few noble Greeks might enter the Roman army, but most athletics in the gymnasium—aside from the numerous professional athletes and their guilds—had degenerated into the practice of “body sculpting.” The Romans did not always go in for this, as Plutarch (a first-century Greek) explains:

For the Romans used to be very suspicious of rubbing down with oil, and even today they believe that nothing has been so much to blame for the enslavement and effeminacy of the Greeks as their gymnasia and wrestling-schools, which engender much listless idleness and waste of time in their cities, as well as pederasty and the ruin of the bodies of the young men with regulated sleeping, walking, rhythmical movements, and strict diet; by these practices they have unconsciously lapsed from the practice of arms, and have become content to be termed nimble athletes and handsome wrestlers. (Plutarch, Roman Questions, 40; LCL translation)

GYMNASIUM

The remains of the gymnasium at Laodicea.

The living God, who is the Savior (4:10). In first-century society, the word “savior” was familiar as the title of gods, emperors, provincial governors, and other patrons who provided certain earthly benefactions to communities or individuals in time of need. “Savior” was virtually synonymous with “benefactor.” This can be easily substantiated, but an inscription from Ephesus illustrates this point by using the two words in parallel. The guild of silversmiths honored a provincial governor as “their own savior and benefactor in all things.”47

One especially important example of “savior” relating to earthly benefactions comes from a recovered statue base inscription from Ephesus, which Timothy may have seen many times by the time he read this letter—recall that it was received at Ephesus (1:3). The statue was erected in honor of Julius Caesar in 48 B.C. after he had saved the province from financial ruin. The inscription reads: “The cities of Asia, along with the [citizen-bodies] and the nations, (honor) C. Julius C. f. Caesar, Pontifex Maximus, Emperor, and twice Consul, the manifest god (sprung) from Ares and Aphrodite, and universal savior of human life” (IvE 251; emphasis added). Both Caesar’s divine honors and the “savior” title are of interest, for, in contrast, Paul says that we have set our hope in a living God—not this long-dead “manifest god”—and that our living God is the true benefactor of even these misguided pagans, “and especially of those who believe.” In other words, Paul’s statement in 4:10 has a polemical side effect in its original context.48

The Character of Timothy’s Public Ministry (4:11–16)

Young pastors everywhere have taken encouragement from 4:11–12. In both the Roman and the Greek world, social and political leadership belonged to older men. The Latin word senate comes from senex, “old, senior.” At Athens and other Hellenic cities like Ephesus, there was a semiofficial body of elders, the Gerousia (from Gk., geron, “old man”), which played an important role in politics, religion, and society. Elders played a key role in the church also, and we read about “the elders” of Ephesus in Acts 20:17.49

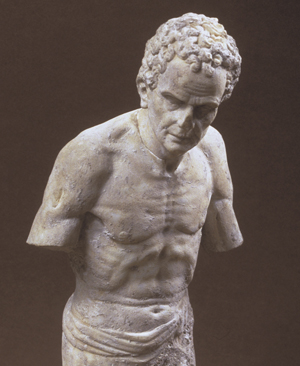

AN OLDER MAN

Roman statue of an older man.

In this ancient climate, one can appreciate Timothy’s delicate position as a leader in the church. He is told to “command and teach these things,” even to people who were senior to him in age. This might lead to pride, but the guard against this is found at the end of 4:12: The young pastor is to execute his office in an exemplary fashion with love and purity. To minister like this from the heart will naturally foster humility. A teacher is a servant.

The public reading of Scripture (4:13). Notice here how central the Word of God is to Timothy’s ministry. He is to devote himself to its public reading, proclamation, and teaching. We take the Bible for granted today. In Timothy’s day, even though books were widely available (2 Tim. 4:13), they were expensive, and not everyone could read. Thus the public reading and proclamation of the Word was especially vital for the health of the church. It was so important that God gave a special attestation of Timothy’s ordination to this ministry “through a prophetic message” when the “body of elders” (Gk. presbyteros) laid their hands on him. This body was probably the Ephesian group whom Paul addressed in nearby Miletus (Acts 20:17). There were no religions in antiquity as “bookish” as Christianity except Judaism (e.g., Acts 15:21).

Be diligent in these matters (4:15). The young pastor is to be especially diligent and watchful both in his progress in sanctification and in his doctrine. Life and doctrine must never be separated in either the minister or in the church. They are the guarantee of perseverance in our holy faith, leading to salvation “both for yourself and your hearers.”