Mister Dwarf Carozo Minujín hopped out of the carriage and politely offered his hand to help me down after him.

I unrolled myself as best I could and jumped down onto the ground. I looked around carefully and then asked, a little disappointed:

“So, this is your famous Forest of Gulubú?”

“The very same,” he replied, very pleased with himself.

“But I don’t see a forest anywhere,” I said.

And my companions and my family and the busybodies all joined in:

“We don’t see a forest anywhere! Why have you brought us all this way?”

“Supisichi,” replied the dwarf, which calmed us down a great deal.

When we were all just about ready to have our bottom lips start quivering, the little dwarf took a few steps forward and said some magic words, which were:

“Chipiti-chapiti-bampiti-boom…”

… or something like that, I think. He walked over to some pieces of wire and pulled. We all thought he was crazy, when we saw him holding on to some quite ordinary wires—just those regular ones that grow wild on a normal wire fence—but we were wrong.

Not only was he not crazy, but the wires were magical, and the moment he pulled them… Ker-BLAM!

Have you seen those pop-up books that you open and the characters suddenly stand up inside them?

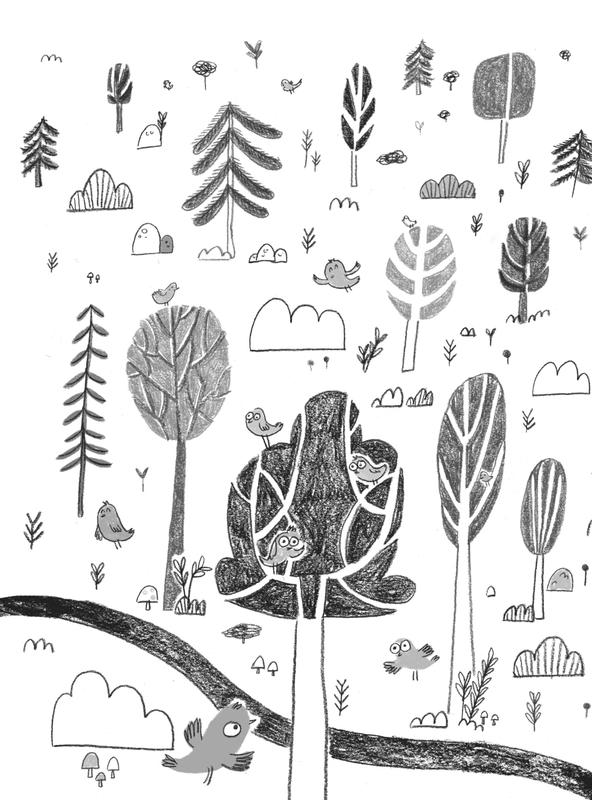

Well, the Forest of Gulubú is just like that. As if it were filled with sleeping marionettes. You give a little pull on their strings and they’re up on their feet, dancing and moving about.

The Forest of Gulubú is ironed flat on the ground, and when its owner pulls on the wires, the trees and the grasses and the cottages and the animals all appear suddenly, as if to say:

“Here we are! We were just playing hide-and-seek.”

You can imagine our surprise. My Auntie Clodomira fainted, with pretty good aim this time because she fell right into the arms of the Superintendent.

It’s not every day you see a forest rising up from the ground, just like that, in a place where a moment ago there was nothing but a bit of open pasture and which, it would seem, is not all that far from the town of Ituzaingó.

None of us could believe it. We rubbed our eyes and our jaws dropped.

Dailan Kifki was utterly delighted. He knelt down to allow people to dismount from his head and back, using his trunk as a slide. And the moment he felt free of that enormous weight he trotted off into the Forest of Gulubú, no doubt hoping to find himself a banana tree, or a pear tree, or an oats-soup tree.

Meanwhile the rest of us walked into the forest with the dwarf, who wouldn’t let go of my hand. He explained that whenever he went off on a trip he would flatten the forest and leave it lying down and invisible so that nobody would steal it or spoil it. I remarked that he was right to do so; it was worth taking good care of such a handsome forest. Because I must tell you, that Forest of Gulubú isn’t just any old forest. It’s certainly not some inferior little forest like Granddad said it was.

Not at all. It’s very big and very real, like one of those forests that only exist in stories. With trees filled with wise little birds, the kind that aren’t just painted but completely alive. With a delightful stream where there are frogs learning to swim, in polka-dot swimming-trunks, and where Dailan Kifki had rushed to give his trunk a drink until Mister Carozo shooed him away, because he was drinking so much he was going to dry it out completely.

In this forest there were toads smoking pipes and big toadstools with fridges and TV sets. Rabbits cycled past, and—strangest of all, I thought—there were canaries with cages. But those birds weren’t inside the cages. They were carrying them around like briefcases, filled with all their school equipment.

We were all very happy as we walked through the Forest of Gulubú, breathing in a delicious scent of peppermints, finally having a rest after so much coming and going and turning around and around, when Granddad, as usual, decided to throw cold water on our party.

He stood up on a tree trunk and shouted:

“Quiet, children!”

We all fell silent.

When Granddad saw that the silence was so complete that even the birds were dumbstruck and the canaries had stopped in mid-air to listen to him, he said, solemnly:

“Now that we have arrived in this forest, following a long and arduous voyage through dangerous and unknown regions, I shall immediately be giving you an illustrated zoology and botany lesson.”

I’m sure you can imagine how much we all felt like having a lesson just then, can’t you?

My brother Roberto said:

“We’re toast.”

Once again, I had to admit he was right.