Composers are a special breed of artist. They create the songs we walk around with in our heads for all of our lives. But how do they know what particular notes to put next to each other that will bring a tear or a smile, or make the skin on our arms stand on end?

I’ve been blessed to sing songs composed by some of the greatest composers in pop music (though I’m not going to list them here and risk leaving out a couple). But I’ve got to say I have a special place in my heart for Harold Arlen. His songs were unique and unconventional—almost like plays that swung among joy, regret, resignation, and celebration in just two to three minutes.

Singers admire Harold’s compositions but approach them with caution. Many of his most popular songs have big leaps between notes that can challenge a performer. There’s no better example than Harold’s “Over the Rainbow.” The very first two notes jump a full octave, from middle C to the C above middle C. I’m sure there are music teachers out there who tell their students not to do that to a singer—or a song.

But “Over the Rainbow” has been ranked as the Song of the Century in a poll by the National Endowment of the Arts and is widely considered the greatest movie song of all time.

(Yip Harburg, one of Harold’s best creative partners, wrote the haunting lyrics. In 1939, Harold and Yip also wrote “Lydia, the Tattooed Lady” for Groucho Marx, which may be the funniest song of all time. That’s range!)

The Harold Arlen I knew was a dapper gent, who always wore a fresh flower in his lapel. He had a beautifully groomed mustache that gave him a dash of Errol Flynn. He was the son of a cantor from Buffalo, New York (his name at birth was Hyman Arluck; Arlen came from Orlin, his mother’s maiden name), and was fascinated by blues and jazz from an early age. Harold could also sing and play a superb piano, and he toured with his own group for much of his twenties, then began to write shows for the famous Cotton Club in Harlem. His lyric writing partner then was Ted Koehler, and they created scores of gorgeous songs that are standards today, including “Stormy Weather” (the great Ethel Waters cut the first recording, and it’s still a classic) and “Let’s Fall in Love.”

Love is what brought Harold to Hollywood in the 1930s. He married a stunning model and starlet named Anya Taranda, who was one of the original Breck Shampoo girls, and they were devoted to each other. But their marriage was not an easy melody. Anya had mental and emotional problems and had to be institutionalized for seven years. I’ve always wondered how that experience might have deepened Harold, and inflected some of his best-known songs with a touch of his own blues.

It was in Hollywood that he teamed up with Yip Harburg. I’ve heard a couple of different versions of how they came up with “Over the Rainbow” in 1936, including one that says Harold saw a rainbow over Schwab’s drugstore. In other interviews, he just said he was on a drive with Anya when the first notes came to him. But remember, The Wizard of Oz had several popular songs, including “If I Only Had a Brain” (Ray Bolger’s Scarecrow) or “a Heart” (Jack Haley’s Tin Man) or “the Nerve” (Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion—maybe I ought to say “Da Noive”) and “We’re Off to See the Wizard.” Harold and Yip were on staff at MGM, so they received no royalties.

In the 1940s, Harold started songwriting with Johnny Mercer, the great lyricist, and they produced one classic after another, including “Blues in the Night,” “That Old Black Magic,” “Come Rain or Come Shine,” and “One for My Baby.” And in the 1950s, Harold teamed with Ira Gershwin to write “The Man That Got Away” for Judy Garland in A Star Is Born.

So Harold Arlen wrote Judy Garland’s signature songs both when she was young and when she was mature, and they happen to be perhaps the two greatest movie songs of all time. That’s a good life’s work, all by itself.

I loved Harold’s song “So Long, Big Time!” and wanted to record it for my 1964 album The Many Moods of Tony. I was honored when Harold came to the recording session. That was rare for him. But “So Long, Big Time!” was a brand-new song. It had a wonderful lyric by Dorothy Langdon (later known as Dory Previn), the story of a man who was once up and is now down. “So long, so long / Big time / Big dough, bright lights / Big time.”

We were excited to see Harold behind the control room glass, elegant with his fresh flower in his lapel, and wanted to do our best by his song. A lot of songwriters, for reasons I respect, don’t want you to tinker with what they’ve written. They work hard to put every note and word into place, and their work deserves to be treated with deference.

But Harold didn’t mind improvisation. He’d actually become enthusiastic about changes we would try from take to take, telling us “Hey, change it any way you like, as long as it works.” In fact, Harold himself had suggestions about certain words I should hit, such as emphasizing the rhyme in “It was fun / Now it’s done.”

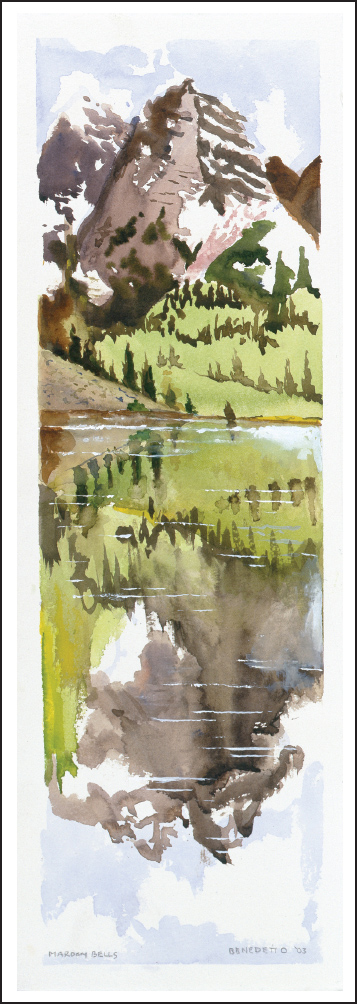

Maroon Bells

Harold was secure as an artist. He knew that there was something so identifiable at the core of his songs that he didn’t worry about changes. He understood, as artists must, that you roll what you create into the world, and then it flies away on its own. The world takes over from there. His example helped me see that I should enjoy and treasure collaboration. Nobody has all the best ideas, and working with others helps keep you fresh and invigorated. That’s how Harold wrote all those great songs year after year, decade after decade.

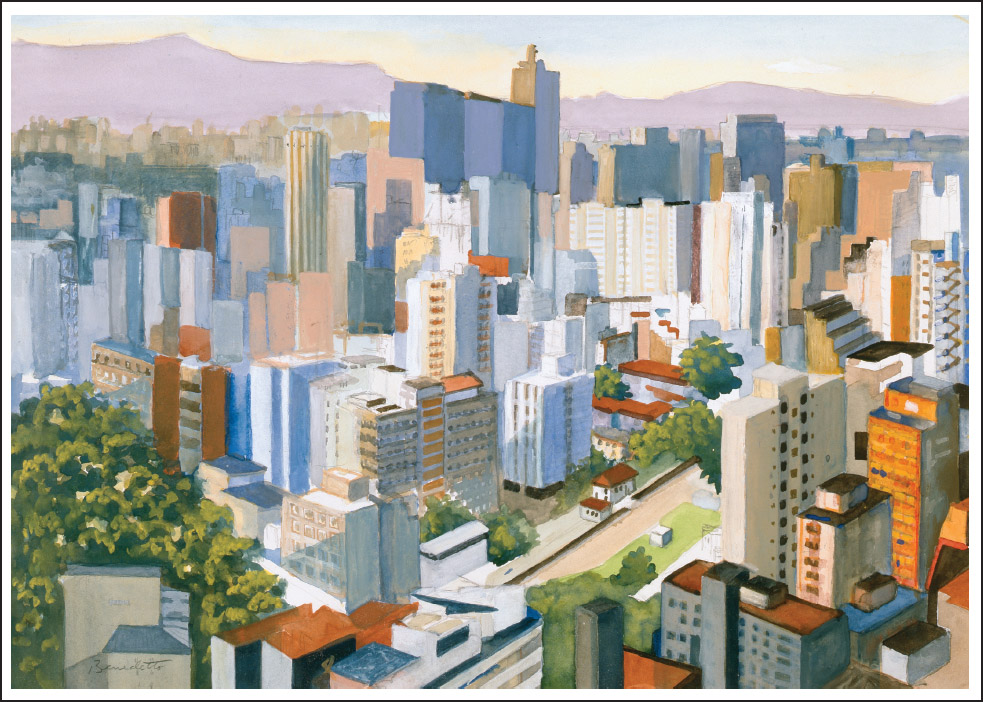

São Paulo, Brazil