One of the most treasured photos that I keep in my office shows my friend Harry Belafonte and me smiling on either side of his friend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The picture was snapped backstage at Carnegie Hall in January 1961 at a tribute to Dr. King to benefit his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (Count Basie was also there, along with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Mahalia Jackson, Carmen McRae, Buddy Hackett, and many more stars of the caliber that only a great cause—and Harry Belafonte—could bring together).

Anyone can look at himself in an old photo and reflect, “How young I was.” But I look at that photo and realize that Dr. King was just thirty-two, a couple of years younger than Harry and me. Yet he was already an international hero for his amazing oratory and boundless courage in leading countless civil rights campaigns and demonstrations.

He was gracious to all of us backstage and carried himself with such dignity and princely bearing that you knew you were in the presence of someone who was a great soul. It’s a little startling to look at that photo and realize how much a man who was barely into his thirties had already shaken history and inspired the world.

I owe a lot to Dr. Martin Luther King. Every American does.

If they have room for another bust on Mount Rushmore, it should be of Dr. King. Not only did he give his life for equal rights for all Americans, he showed us how to return hatred with love. He was Gandhi’s message of peace and nonviolence in a walking, breathing, brave human being.

But those of us in the music business owe a special debt to Dr. King and the civil rights revolution that he and others brought about with such great effort and cost. We knew the genius of so many African Americans firsthand: it was in the music we performed every day. We would not have had our careers—our lives—without the gifts of the African American artists who created jazz and the blues, our great American musical art forms.

We also knew that for a long time, a lot of our greatest musical geniuses—Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Nat “King” Cole, as well as millions of other people—could not even sit at the same table we did in a restaurant. I don’t know how many times I’d come to see Nat or Ella perform in a supper club where they would bring in hundreds of people but couldn’t walk in through the same door or be a customer. America was crazy.

Martin Luther King electrified me when I first saw him on grainy black-and-white news film in the late 1950s. You could glimpse the majesty of his character, even in short clips. And there was a powerful musicality in his speeches, with his great voice pealing like a golden trumpet as he asked a crowd how long their struggle would last.

“How long? Not long! Because no lie can live forever. How long? Not long! Because ‘you shall reap what you sow,’” and the crowd coming back with “Yes sir, Doctor.” “How long? Not long! Because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice . . .”

Harry Belafonte called me in March 1965. Dr. King and his lieutenants had been organizing and leading peaceful marches and protests to assert the right of blacks to register to vote. After a rally in late February, a twenty-six-year-old church deacon named Jimmie Lee Jackson had been clubbed and shot to death by Alabama state troopers (the trooper who pulled the trigger, James Bonard Fowler, wouldn’t be indicted until 2007 and pleaded guilty to second-degree manslaughter, serving just five months in prison for the death of an innocent man).

Reverend James Bevel of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference mapped out three long marches, fifty-four miles, from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. The first march, on March 7, 1965, became known as Bloody Sunday after state troopers attacked the marchers with tear gas and billy clubs. Dr. King himself led the next march, on March 9; to avoid a confrontation, he just led the group back to a church. But that night, a group of white thugs beat and killed the Reverend James Reeb, a minister from Boston who had joined the march (four men would be indicted for his death, but three were acquitted by all-white juries, and the fourth fled to Mississippi and never stood trial).

The third march was set for March 21, 1965. “We need you, Tony,” Harry said when he reached me. “People are being slaughtered all over Alabama.”

The governor of Alabama, George Wallace, refused to protect the marchers. So President Lyndon Johnson said he would federalize the Alabama National Guard and send two thousand US Army soldiers and an army of federal marshals and FBI agents to Alabama.

“I hate violence, Harry,” I told him. “I saw too much of it during the war.”

“That’s why we need you, Tony,” he told me. “To try to stop the violence.”

So I went down to Selma for the third and final march. Dr. King and Harry had also persuaded some other performers, including Sammy Davis, Jr., Shelley Winters, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and Leonard Bernstein, to join the march. I roomed with my old friend Billy Eckstine, the great deep-voiced, and drop-dead-handsome singer, and we joined people from all over the country to march ten miles a day along what was then called in Alabama the Jefferson Davis Highway.

It was thrilling and inspiring to march. But also a little frightening—more than a little. The state troopers cursed and spat along the route, and tapped their guns and billy clubs. Everyone knew that blood had already been shed. I hadn’t been so frightened since my days in a foxhole in Germany. But Alabama was supposed to be in the United States of America.

One night, Dr. King asked us performers to put on a show. It was the least we could do for such brave people. No stage was available—the state troopers wouldn’t permit an integrated group to perform in a theater or school along the route—so someone called a nearby funeral home. A local mortician rolled out his inventory. We did a show on top of eighteen wooden caskets that became our stage. I sang a few numbers, but the only song I really remember is “Just in Time,” which now seems kind of oddly appropriate.

Both Billy and I had previous engagements that couldn’t be canceled and we had to leave before the march ended in Montgomery. We must have been a little jumpy and distracted when we packed, because a few days later, Billy called me in New York from Los Angeles.

“Tony,” he said in that deep, mellifluous voice that had made such hits of “Blue Moon” and “Sophisticated Lady,” “where are my damn pants?” Billy was six foot two, I was five foot nine, but we had packed each other’s pants and been too nervous to notice.

Yet the full impact of events wouldn’t strike us until a few days later. Billy and I had been given a lift to the airport by a mother of five from Detroit, who told us she had heard Martin Luther King, Jr., say that the struggle for equal rights going on in Alabama was for all Americans. So she had driven down to Selma to try to help. Because she had a ’63 Oldsmobile (and probably because she was white and less likely to be stopped by state troopers), Viola Liuzzo was assigned to ferry supplies between the march sites and many of the volunteers arriving from all over the country.

I wish I could tell you that I remember our conversation when she drove Billy and me to the Montgomery airport. I just remember admiring this bold, appealing woman—a mother of five kids who was putting herself on the line for civil rights.

Billy and I played our gigs and picked up our lives in show business. Meanwhile, Viola Liuzzo stayed on to see the great Selma-to-Montgomery march finally reach the end on March 25, 1965. A Confederate flag flew over the state capitol, but Martin Luther King told the crowd, “Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.”

What magnificence of soul and spirit for a man who had been stung so much by the lash of segregation.

After the march, Viola and another volunteer, a nineteen-year-old named Leroy Moton, drove some of the marchers back to Selma. They had turned around to head back to Montgomery and were stopped at a red light when four white men—Ku Klux Klan members—pulled up alongside and began to follow them. Viola Liuzzo tried to outrun them, but the men waited for a remote stretch of highway and opened fire.

They murdered Viola Liuzzo, a courageous mother of five from Detroit who gave her life for civil rights. She was only thirty-nine years old—the same age as Martin Luther King when he was assassinated just three years later.

My personal contact with Martin Luther King, Jr., was limited. But his struggle, his achievements, and his living embodiment of the power of love continue to inspire me and millions more. I am as proud (more proud, really, in many ways) to have been a small part, with so many others, of his march from Selma to Montgomery as I am of any Grammy Award or gold record.

We still have a lot of work to do on racial equality in America. We still have a lot of work to do to instill peace. But Dr. King’s great gift to us all was to show us that there’s a path to a better way if we’re bold enough to take it. In my own small way, I try to use my art, my music, and the work we have done in schools to try to help move us along a little more on the path Dr. King so nobly set. He inspires me every day, as much as do the greatest composers and artists. Martin Luther King’s life ended too soon, but it is timeless.

Miyamoto Musashi: Shrike

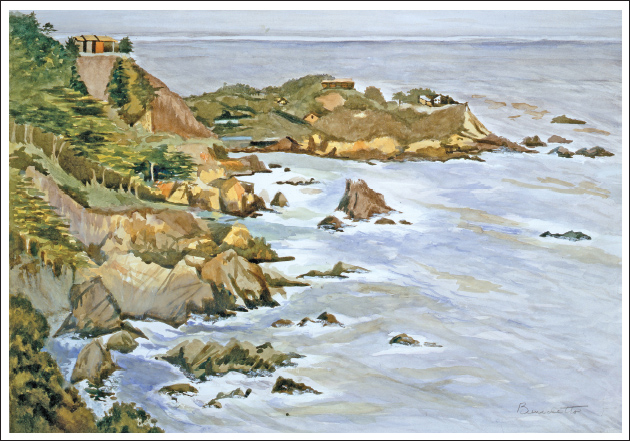

Carmel Highlands, California