Nat “King” Cole was the soul of elegance. He sang like an angel, played piano with precision and grace, and had a generosity that can be rare in any line of work.

But I never will forget (none of us should) that when I went to see him in his dressing room in a Miami club in the 1950s and invited him to join me at my table after the show, he just shook his head and smiled.

“Can’t do that here, Tony,” he told me. “I’ll just have to see you in the dressing room.”

What he meant, of course, was that Miami and the rest of the South (and practically speaking, some places in the North, too) were still segregated. The star of the show—the man whose name packed the house—couldn’t sit at the same table as a customer because of the color of his skin.

I remember hearing Nat on a V-Disc when I was still a soldier in Germany. I didn’t know his name then. But I couldn’t forget how his soft, silky baritone conveyed such warmth and feeling or how his enunciation was so exact and elegant.

Scores of great singers have recorded “Mona Lisa,” the wonderful song by Ray Evans and Jay Livingston; I certainly have. But say the words, and I’ll bet most people think of Nat “King” Cole, maybe even more than they think of Leonardo da Vinci.

Nat told me once that his mother had been his only music teacher. He began with gospel in his Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, but she insisted he learn Bach and Rachmaninoff, too. The South Side rocked with great music when Nat was growing up, and he could stand outside clubs and hear the likes of Jimmie Noone, Earl Hines, and of course Louis Armstrong. Nat’s older brother, Eddie, was a gifted bass player, and they began to pick up work.

Incredibly enough, Nat wasn’t singing in those early days, just playing piano. He got a job playing in the national tour of Eubie Blake’s revue Shuffle Along when it came to Chicago. Nat was just sixteen when he was invited to join the company on the road. Shuffle Along is sometimes called the first all-black musical to reach white audiences, too. The show had been a huge hit on Broadway and in most of the rest of the country. But when the tour came to an end in Long Beach, California, Nat decided that he liked the sun and the laid-back style of California and that he would try his luck there. Success didn’t come all at once, but he never had to look back.

Nat acquired the “King” in his name, he said, when a customer in a club he played put a paper hat on his head and said, “Look, King Cole.” The customer sounds like a jerk. But the name stuck because of Nat’s mastery of music and his dignified, regal bearing.

Southern California abounded with clubs and road joints in those days, and Nat formed a jazz quartet with Oscar Moore on guitar, Wesley Prince on string bass, and Nat at the piano. Nat said that one night the drummer didn’t show up, and the Nat King Cole Trio was born.

To this day, I’m not sure I ever heard the real story of how it was that Nat began to sing in their act. You’d think a voice of his quality couldn’t stay concealed for long. The story that Nat liked to tell (but he told his friends that it wasn’t quite the whole story) was that one night a customer who’d had a little too much to drink (how many stories begin like that?) shouted from his seat that he wanted Nat, on the piano, to sing “Sweet Lorraine.”

Nat told him, “We don’t sing.”

The club owner, according to the story, came over to whisper that the drunken customer was a big spender—and a big tipper. So Nat sang “Sweet Lorraine,” the Cliff Burwell and Mitchell Parish song. It would become the Nat King Cole Trio’s first hit in 1940.

I don’t know what Nat left out of that story. But I always shared his artistic outlook that you shouldn’t tamper with perfection.

Nat and I were both represented by the General Artists Corporation. We met unexpectedly in their offices in New York one afternoon in the mid-1950s. I had just enjoyed a few hits, including “Rags to Riches” and “Strangers in Paradise.” But since Nat’s own jazzy, brilliant “Straighten Up and Fly Right” had come out in 1943, Nat had joined the ranks of Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby at the top of the charts. The signature round headquarters building of Capitol Records near Hollywood and Vine was called “The House that Nat Built,” for all the records he had sold for Capitol.

We got on from the first, both personally and musically. We both loved jazz and found that our singing was influenced by the rhythms and syncopation of great jazz artists. I had taken the bus into New York that day from New Jersey, where I’d visited my mother in the home that I’d bought for her. Nat understood that. He’d gotten a home for his mother in Chicago.

Nat was booked to play the Chez Paree in Chicago in 1956, a great club in which he was always the returning hero. But President Dwight D. Eisenhower invited Nat to sing at the White House at the same time, and he had to bow out of his engagement at Chez Paree. He didn’t want to leave his friends high and dry, so he called them up and said, “Get Tony Bennett.”

I’ll never forget what that meant to me. I’d had a couple of big hits but was still identified as a New York singer. Chicago was the most important market west of New York and had a busy, vibrant club scene. I’d never been able to crack that town with a major booking—but thanks to Nat “King” Cole, I was going into the best club, with his mark of approval. It was a wonderful vote of confidence that Nat “King” Cole’s fans wouldn’t be disappointed by this kid from Queens.

I wound up sharing the bill with the amazing Sophie Tucker. We were supposed to run for a few days, but as we left the stage that first night, Sophie turned to me and said, “Kid, we’re going to run for a month.” We did, and I knew that I had made it in Chicago.

(By the way: Sophie and I both had contracts stipulating that we’d have top billing. The owners of Chez Paree finessed this by putting her name on top on one side of the marquee and mine on the other—then made sure that Sophie, who was one of the biggest draws in show business at the time, was taken to the club only on the side of the street that had her name above mine.)

You’d think an artist booked for the White House at the special invitation of the president wouldn’t be a victim of bigotry. But when Nat and his wife bought a huge, beautiful Tudor mansion in Hancock Park, a swanky district of Los Angeles, an attorney for one of their new neighbors said, “We don’t want undesirable people coming here.”

Nat replied with typical class—more class than the jerk deserved. “Neither do I,” he said. That’s why the name “King” fit him so well.

More alarmingly, one night in 1956, Nat was performing in Birmingham, Alabama, with Ted Heath, the great British bandleader, when three members of the Alabama Citizens’ Council, a white supremacist group, rushed the stage. Reportedly, they wanted to kidnap Nat (they were appalled by a black man playing for a white audience but wouldn’t mind taking money from the rich black man’s family). The men were arrested before much of anything could happen. But Nat was knocked from his piano bench in the commotion, didn’t finish the concert, and never—ever—played the South again.

Shortly after he appeared at the White House, NBC asked Nat to host his own weekly show on Monday nights. The Nat “King” Cole Show was the first major variety show to be hosted by a black entertainer and, boy, did he get great guests, including Ella Fitzgerald, Peggy Lee, Frankie Laine, Mel Tormé, and Eartha Kitt. When Nat “King” Cole invited you onto national television, you said yes.

But in the mid-1950s, NBC could never get a national sponsor for the show, and it ended—Nat himself suggested the cancellation—after just a year.

Nat told the newspapers, “I guess Madison Avenue is afraid of the dark.”

It’s a little funny to think these days that if an inebriated customer hadn’t shouted, “Sing ‘Sweet Lorraine’!” we might never have discovered Nat’s supremely silky voice, which is still heard around the world, even in our dreams. Nat always said that he just sang the feelings that were in him. That sounds so simple, but of course it’s not. He sang with the gifts of a great pianist: precision, shading, touch, and feeling. And I don’t know of any other singer who had huge hits in at least three languages (“Darling, Je Vous Aime Beaucoup,” including three albums in Spanish—though the Hotel Nacional de Cuba in Havana still wouldn’t let him stay there when he recorded one of those albums in 1956; American-style segregation was the rule there, too).

When the rock revolution took over the charts, Nat managed better than some of the rest of us, with “Ramblin’ Rose,” “That Sunday, That Summer,” and “Those Lazy-Hazy-Crazy Days of Summer” all hitting in the top ten.

Nat and I were both playing Las Vegas when “Ramblin’ Rose” was the number one hit in America. I couldn’t go to his shows, so I stopped by to visit during his rehearsal. He was working on a bit where he wanted to walk through the audience, singing. For some reason Jack Entratter, who owned the Sands, told Nat that he didn’t like the idea (I wonder now if he worried that someone in the audience might misbehave). The room was dark, except for the light that followed Nat, so from the darkness, I just piped up, “Don’t worry, Nat, you have the number one song in the country. Do whatever you want.”

Both Nat and Jack cracked up, and Nat got his way.

Nat called me in the middle of 1964 to say that he was going to open a new hall in Los Angeles (he never quite mentioned that it was the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion) and that he wanted me, Ella Fitzgerald, and Count Basie to appear with him. Of course we all instantly agreed. Every few weeks, Nat would call just to check. “You’ve got it on your calendar, right?” he’d ask.

I didn’t think much of anything when I didn’t hear from Nat for a few weeks, but then I ran into Dean Martin.

“Nat has lung cancer,” he told me.

Nat was in the hospital in Santa Monica, undergoing cobalt treatments, when the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion opened that December. Frank Sinatra took over the show, and it became a tribute to Nat. He was the talent that brought us all together, and his presence filled the hall on that historic first night.

Nat was briefly released from the hospital over the holidays but returned to the hospital in January and had a lung removed. You had to wonder what went through the mind of a great singer when he heard that the doctors had had to do that. But Nat was fighting for his life by then, not just a singing career. I know I would have stood in line to hear Nat “King” Cole sing with any breath that he could muster.

I started on tour with Bobby Hackett, the great cornet and trumpet player, early in 1965, and we were playing the Palmer House in Nat’s own Chicago when we got word that Nat had died. He was just forty-five. I don’t think most of the audience knew yet. Bobby and I looked at each other and asked, “What do we say? What do we play?” Then we simultaneously said, “‘Sweet Lorraine.’”

I like to think that I would have eventually found a national audience for my music under any circumstances. But that night in his hometown, I knew how lucky I had been to receive Nat’s endorsement and generosity. His faith in me, as much as anything else, gave me my own confidence.

And in 2001, when I got to sing “Stormy Weather” with Nat’s beautiful and beloved daughter, Natalie, I felt as if I were somehow doing that last show with Nat that we never got the chance to do.

Then, a few years later, the beautiful Natalie Cole left us too soon, too.

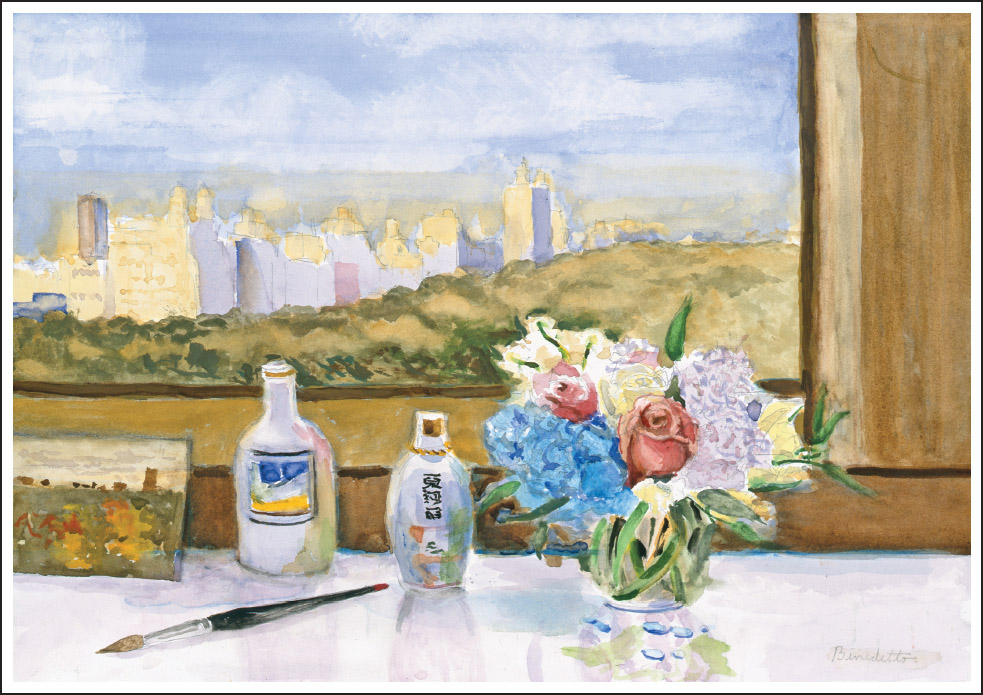

New York Still Life