I’ve tried to live a life in which I’ve been proud of every song that I’ve ever recorded. But I’m prouder of nothing more than the two albums I did with the great pianist and composer Bill Evans, The Tony Bennett/Bill Evans Album in 1975 and Together Again in 1977.

Our friend Annie Ross, the great British jazz singer, proposed the idea one night when we were having dinner in London. Of course I knew the name. Bill Evans was probably the most legendary jazz pianist in the world at the time. He had played with Miles Davis’s sextet when they recorded Kind of Blue, which is considered just about the most influential, and certainly the best-selling, jazz album of all time.

But I knew that Bill didn’t often record with singers. His stellar use of impressionist harmonies and block chords (chords built directly below the melody, usually on the strong beats) were considered as innovative as those of Miles. But they would be an extra challenge for singers. Bill’s genius usually had to be on its own. His solo 1963 album, Conversations with Myself, was one of the first uses of overdubbing, so that he could essentially accompany himself.

People spoke about him with awe and a little bit of mystery. Bill Evans was quiet and scholarly, a quintessential jazzman with classical training.

“Bill had this quiet fire that I loved on piano,” Miles once said of him. “The sound he got was like crystal notes or water cascading down from some waterfall.”

Bill happened to be playing in London at the time, so we went down to hear him. I was filled with awe, the way his hands seemed to hover over the keys, then lightly, precisely strike a note. I also found him to be friendly and approachable—a shy, warm kind of genius. He looked like a college professor, with round glasses softening his fierce, almost flinty eyes.

So in the spring of 1975, we worked out a deal to tape two albums with each other, one for Improv, which was then my label, and one for Bill’s label, Fantasy.

“Keep your cronies at home, and I’ll do the same,” Bill told me. He wanted the sound of just two artists improvising with and inspiring each other without distraction. So it was just Bill, me, and an engineer in the studio, with Helen Keane, Bill’s great manager, looking on through the glass as our producer.

It was one of the most intense musical experiences of my life. I’d suggest a tune, and Bill would say, “Good, let’s try that.” We’d find a key, then work it out note by note. No take—no measure—was the same as the next. Bill was always changing, jamming, winging it, and inviting me to come along.

You’d think you’d know a song—a standard like Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “The Days of Wine and Roses”—but Bill would turn it over, note by note, phrase by phrase. It was like setting off on a great expedition and never knowing what was around the next turn—but you couldn’t wait to find out.

I cherish those two albums we produced. Bill’s own great song “Waltz for Debby,” which was written for Bill’s niece, Debby, and a song to break the heart of any father (“In her own sweet world / populated by dolls and clowns / and a prince and a big purple bear . . .”) is on that first album, along with “The Days of Wine and Roses.” The second includes Comden and Green’s “Make Someone Happy” and Bill’s own haunting “You Must Believe in Spring.”

But Bill couldn’t seem to find the spring for himself. At some point in the sixties or seventies, he had become hooked on cocaine, heroin, alcohol—to this day I’m not sure what and how much. We toured together after the albums and appeared at Carnegie Hall, at the Smithsonian, and in a great television concert in the Netherlands. But Bill was so sick by then, he’d live just to go onstage for a set, then go off and lie down in his dressing room.

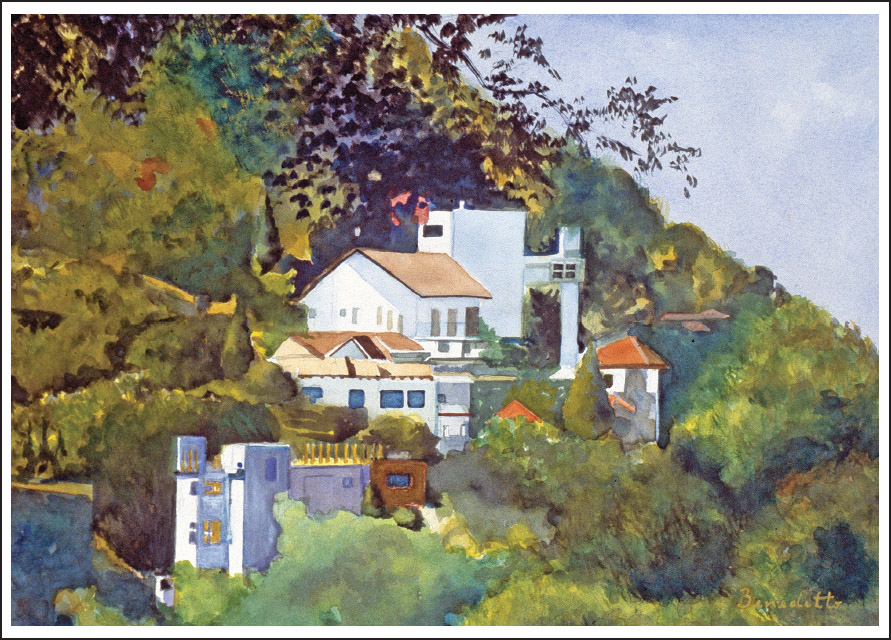

Houses in Trees

I loved Bill. A lot of people in show business (including me, I have to confess) used cocaine during that time, and we all kind of pretended with each other that it wasn’t a problem. We told each other, in so many ways, that drugs were just what creative people used to open their imagination or soften the harsh realities of an unfair world.

But drugs began to take over Bill’s life and leave room for little else. I had to ask him once, “What happened? Did someone hurt you?”

And Bill told me, “I wish they had. I wish somebody had broken my arm instead of sticking a needle in it for the first time. I wish somebody would have knocked me out so that I’d never touch it again.”

The last time I talked to Bill was probably early 1980. He was able to track me down in a small town in Texas, where I was between gigs, and I didn’t understand what was so urgent that he had to reach me so suddenly. I later learned that his beloved older brother, Harry, had taken his own life, which devastated Bill (he wrote one of his last songs for him, too, “We Will Meet Again,” and it’s beautiful, touching, and wrenching all at once).

“I wanted to tell you one thing,” Bill said over the phone. “Just think truth and beauty. Forget about everything else. Just truth and beauty, that’s all.”

Bill had stopped his treatments for chronic hepatitis. It might have been a slow-motion way of joining his brother. Bill Evans left us in September 1980, and I can’t stop thinking of all the music he left behind and all the music he didn’t live to make.

His loss sobered me—in all ways. I missed my friend and creative partner. And, I knew, I’d be foolhardy not to see Bill’s loss as an alarm bell for my own life.

Those two great albums we recorded? You practically couldn’t give them away when they came out. But now they’re considered classics and have sold far more in reissue. Sometimes the world just needs to catch up with what you’re doing. As Bill Evans said, truth and beauty, that’s all.

Spring in Manhattan