Frank Sinatra did one of the most caring things that any colleague of mine in the industry has done in my entire career, and I will always be grateful to him for that alone. In the autumn of 1974, Frank knew that my mother was nearing the end of her life, and was pretty sure that she and I would be watching his televised concert from Madison Square Garden, Sinatra: The Main Event. At one point between songs, talking his way into Vernon Duke’s “Autumn in New York,” Frank ad-libbed, “Tony Bennett is my favorite guy in the whole world.” My mother’s face lit up like Times Square. I’d call it a small, loving gesture, except that, of course, it was seen and heard by millions of people. I will never forget how much Frank’s gesture meant to my mom and to me.

Frank Sinatra has been an important part of my life since I was nine, when our family would listen to Major Bowes’ Original Amateur Hour. I was an original bobby-soxer. I’d go to his shows at the Paramount, with thousands of other teenagers, and stay for all seven shows, with girls all around me fainting for Frank. (There would later be academic papers written about this phenomenon, which seemed to escalate because we couldn’t bring food to our seats or go out to use the bathroom without giving up our places—so kids would faint.)

What I remember most vividly about Frank from those years when I saw him from a distance, when I was just a fan who was not yet his friend, was the utter clarity of his phrasing. He worked at it as hard as Meryl Streep ever would to perfect an accent. Frank sang every vowel and consonant of every word; it’s one of the (many) reasons why all the great songwriters wanted to work with him.

Listen to Frank’s speaking voice in one of his concerts or on the old radio shows, or in one of his great movies, like From Here to Eternity or A Hole in the Head. He sounds like—he is—a Jersey guy. Then listen to “Fly Me to the Moon,” “The Lady is a Tramp,” or his truly astounding rendition of “Ol’ Man River,” in which Frank does not slip into dialect but enunciates every phrase. That clarity was part of revealing the heart of a song, and Frank’s own heart. In his early days, Frank was part of a singing group called the Hoboken Four, who won the contest one week in September 1935, when our family was listening. When Major Edward Bowes asked, in his booming, intimidating voice, “Who will speak for this group?” I heard a confident young voice come right back at him: “I will. I’m Frankie. We’re looking for jobs. How ’bout it?” Frank Sinatra was all of nineteen.

The jobs kept coming, too. Frank and the group became such popular winners that Major Bowes decided to keep bringing them back, but under different names. One week they’d be the Seacaucus Cockamamies. Another they’d be the Bayonne Baccalàs (baccalà is an Italian delicacy of dried salt cod). But whatever they were called, Frank’s group always won.

By 1939, Frank was singing with the Harry James Orchestra. Within a year, the great Tommy Dorsey recruited him for his band. Frank and Tommy would become famous together, argue together, have a nasty split, and wind up being friends again. When I look back on it, I think their split was inevitable: no band, even the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, would be big enough to keep Frank Sinatra to itself. But in time, each of them grew to see what they owed the other. By 1940, Frank’s singing and popularity put Tommy’s band ahead of all others. Frank always told me that Tommy taught him how to be a better singer, a better artist, and a better man.

Frank studied the way Tommy played the jazz trombone and applied those lessons to his own voice. He worked to expand his breathing (he spent a lot of time swimming underwater at public pools, among other exercises) so that he could sing two or three lines without taking a breath. It made the audience pay attention to and hang on his every phrase. It made, to quote Tommy, the “skinny kid with big ears” into an object of adoration. The “swooning” that began for Frank was for the way he would sweep you away with that clear, lyrical, soaring, sweet voice.

I didn’t get to meet Frank until the spring of 1956, when I was given the chance to take over Perry Como’s slot on a summer replacement show. I was just coming off the success of my recording of “Stranger in Paradise,” which made a hit of a song from Kismet, the Robert Wright and George Forrest musical that had the bad luck of premiering in the middle of a New York newspaper strike.

I soon discovered that though I was taking over Perry’s slot that summer, I was hardly taking over his show. The Perry Como Show was a full-scale production, week after week, with big-name guest stars, elaborate sets, and a full orchestra and chorus. But NBC decided to save money during the summer (when, to be fair, the audiences were smaller) by making the “Tony Bennett Keeps Perry Como’s Slot Warm during the Summer” show a bargain-basement production, with just me on an empty stage with a ten-piece orchestra. I worried if anyone would watch, at least for more than ten minutes. Frank had repaired relations with Tommy Dorsey by then, and was playing the Paramount again with Tommy and his orchestra. I decided to ask Frank for advice.

I had heard in show business circles that Frank liked my singing. But even now, whatever possessed me to show up, unannounced, backstage to ask for the favor of his advice still baffles me a little. Some people who had been on the periphery of Frank’s entourage told me that it wouldn’t be a good idea to approach him. They said he could be moody and unpredictable. But I went to the backstage entrance of the Paramount, where they knew me pretty well from my own shows, and someone slipped back to tell him that Tony Bennett would like to see him. I waited just a few nervous minutes before a man led me back to Frank’s dressing room. I took a breath. Frank was unperturbed by the interruption. I told him about my worries for the summer replacement show, and Frank listened with great courtesy. Then the biggest man in show business said, “Tony, it’s only natural that you should be nervous. And it’s good. It means that you care. If you don’t care about what you’re doing, why should the audience? But when the audience sees how much you want to please them, they’ll root for you. Remember, they’re only there because they already want to like you. Let them know how much that means to you, and they’ll love you. They’ll support you. Work hard for them, and they’ll cheer hard for you.”

Our meeting lasted only a few minutes—but I walked back out onto Broadway feeling as if my feet weren’t touching the ground. I knew Frank was right. And he made me feel as if I could rise above my fears and do anything. Artists do that for all of us. On that day, Frank taught me to trust and use my anxieties to sharpen and key up my performance. Once you get started, the butterflies in your stomach can help you soar. From that day on, Frank and I were friends.

Now and then, someone who knew him would pass along a compliment. I worked with a great drummer named Mickey Scrima at a gig in Dallas, who said to me once, “Do you know what Frank says about you?” Mickey said, “Frank said about you, ‘That kid’s got four sets of balls.’” Frank Sinatra changed my life in another immediate and direct way: he got me gigs. A lot of people at the top of the heap wouldn’t go out of their way to help someone else try to climb up there.

When Duke Ellington and I performed at the Americana Hotel in Miami Beach in 1960, Frank knew that there was a convention of hotel owners meeting nearby. He brought them in to see our show, and they seemed to have a great time.

For the next ten years, I got bookings in classy spots, and they traced back to that one night.

Then, a few years later, he changed my life again. He was the cover story of Life magazine on April 23, 1965. In talking about the music and singers he enjoyed, Frank said, “For my money, Tony Bennett is the best singer in the business. He excites me when I watch him. He moves me. He’s the singer who gets across what the composer has in mind, and probably a little more.”

Before the ink on the magazine was dry, the phone began to ring off the hook. I was on the road. My manager called and read me the quote. I had to get hold of my emotions. Being called “the best singer in the business” by Frank Sinatra was like . . . well, no simile is really necessary, is it? But I hope it didn’t go to my head. I don’t think it did. On the contrary: it gave me a lot to live up to. It’s still in my mind every time I take the stage.

Frank became just about my best friend. But I wasn’t a member of the Rat Pack or his personal entourage. We had dinner and drinks, and we had laughs. I’d fly in for Frank’s birthday party every year—legendary, historic parties, with Nelson Riddle in one corner, Count Basie in another, Marilyn Monroe, Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, Kim Novak, Dean, Sammy—I could go on. There’d be great music, fabulous food, and gorgeous people all over his place. I used to wonder why, year after year, Frank would make sure I was seated next to a famous old entertainment lawyer and not Cary, Fred, or even Tommy Lasorda, the Dodgers’ manager, who was Frank’s dear friend.

One year I finally figured it out: the lawyer was one of the most influential men in Hollywood. Once again, Frank was trying to do me a favor.

Of course I’ve heard some of the stories about other sides of his personality. I just never saw them. The Frank Sinatra I knew was always a gentleman, a devoted friend, and a man of legendary generosity. He’d call producers and club owners to get work for people who needed it, and he’d get the best doctors in the country to make time to see a parking attendant if he required medical help. He helped his closest friends in a hundred different ways, as well as scores of people he’d just heard about. He’d see someone on the news who had been burned out of her home or a guy who had lost a factory job after twenty or thirty years and send that person a check—no publicity, no attention. It was just something that he did to try to even up the odds in life.

I once read The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, the memoir of a sculptor in Renaissance Italy whose works were coveted by popes and monarchs. Cellini had a keen sense of justice and injustice. He would draw his sword when he thought someone was being unfair, whatever his rank or wealth. I sent Frank a copy of the book and wrote inside it, “If Shirley MacLaine’s philosophy is right, you must have been this cat in another life.” I wonder what life Frank is on to now.

One night in the early ’70s, Ralph Sharon and I were playing Caesars Palace in Las Vegas when Frank asked his pal Vido Musso, the saxophonist, to set up dinner after our respective shows. It was a small restaurant way off the Strip where Frank could unwind and talk about the journey of his life, from Hoboken to the seven shows a day at the Paramount, to Ava and Columbia, and then down in the dumps, to the Oscars, and then back up the mountain to the top. There was a piano in the joint. We started late and stayed late, and just before the first sunlight began to streak into the desert sky through the windows, Frank said, “Tony, before we leave, it would mean a lot to me if you and Ralph could do a song.”

What else could we say but yes? It meant a lot to us, too. Ralph and I conferred and quickly settled on a Jerome Kern tune, with lyrics by Otto Harbach:

Olden days, golden days

days of mad romance and love . . .

Sad am I, glad am I

For today I’m dreamin’ of yesterdays.

By the time we left, the sun was spreading an orange glow over the ride home, and Ralph and I felt we’d been blessed to have an extraordinary moment.

Frank and I shared a stage just a few times together over the years. It was always a special occasion. One time that means just about the most to me was a night we both performed at Bally’s in Atlantic City in 1988.

I wore a white tux—Frank wore a black one. We went back and forth between our various hits and joined in together on “The Lady Is a Tramp.” Toward the end of the show, Frank said, “Here’s one of the prettiest songs in the American library, and no one sings it prettier than this guy.” It was a generous setup for me to sing “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” Then I handed the orchestra off to Frank for him to sing his fabulous John Kander and Fred Ebb anthem “New York, New York,” singing it in a fervent way that makes the song a hymn for everyone, from Ketchikan to Key West, who struggles to do his best and strives to reach the top. Then Frank invited this son of Astoria, Queens, to join him to repeat the last few lines:

Los Angeles Still Life

If I can make it there

I’m gonna make it anywhere

It’s up to you, New York, New York!

We took our bows, the houselights dimmed, and people threw bouquets onto the stage. Frank reached out for an armful of roses, removed a flower, and put it into my lapel. We walked offstage to a standing ovation, arm in arm.

He was my best friend.

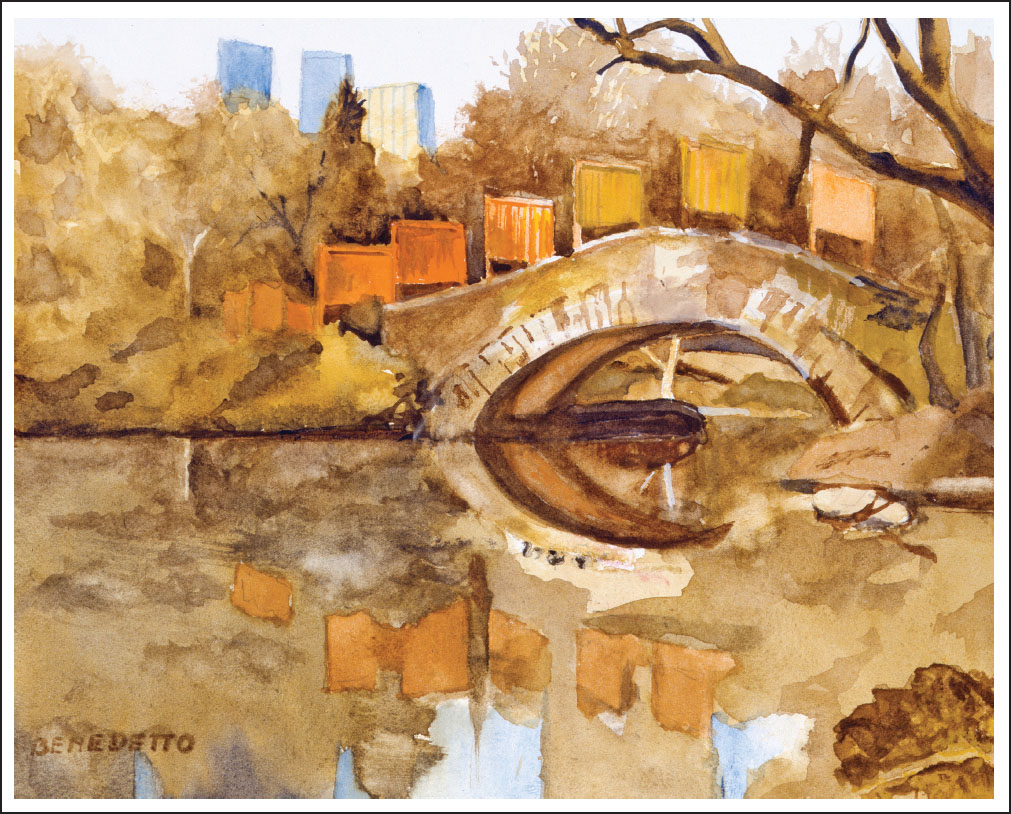

Christos Gates, Central Park