I was a lucky high school kid when I saw the greatest entertainer in America. He sure didn’t look the part. He was hunched over, bald, and—he’d be the first to say this—wouldn’t be confused with Errol Flynn. He played the piano with more zest than finesse. And he sang—barely—in a croaky, raspy voice.

But boy, did Jimmy Durante have personality.

I was probably about fourteen or fifteen and a student at Industrial Arts High School when a girl who must have liked me a little more than I liked her (because I’m afraid I just can’t remember her name) invited me to go to the Copacabana. I think her father had some connection to the club—good enough to get us in and a pretty good table.

Jimmy Durante was the star. He owned the stage from the moment he sauntered out in his squashed fedora and tux, plopped down at the piano, and began to play, almost as if he were banging out a melody on a bunch of cans. He sang almost like a man who was drowning and shouting for help. And every minute or so, he would lift his hands and say, “Stop da music! Stop da music!” to tell some joke. He was outrageous, original, and totally marvelous.

The girl took me backstage, and as we approached Jimmy’s dressing room, we saw just his nose—the famous Durante schnozzola, as he called it—poke out from one side of the door frame. Then the rest of Jimmy turned the corner, laughing, to say hello.

He invited us in. He put his hand, in a fatherly way, on my head. I wish I could better remember what we talked about, but I remember that he both entertained us and really listened to a couple of kids. Jimmy himself had left school in the seventh grade to enter show business. He had formed an act with his cousin, who was also named Jimmy Durante, then branched out on his own, playing ragtime and jazz and adding his signature humor. “I got a million of ’em!”

He went out to Hollywood and became a big star on the strength of his charm, ingenuity, and humor. Hollywood had thousands of handsome men and pretty good singers. But there was only one Jimmy Durante. He made a lot of films that are hard to remember now—Blondie of the Follies, The Phantom President, What! No Beer? (Buster Keaton’s last film), and Palooka.

Jimmy usually played the comic sidekick who had a featured musical number. He sang his own song, “Inka Dinka Doo,” to a store window mannequin in Palooka, and the record of the song he recorded thereafter became one of the biggest hits of the 1930s. A few other singers have dared to record it, including Sammy Davis, Jr., and Ann-Margret. But really, only Jimmy’s version is remembered today. You needed his charm and personality to put across a song that is not much more than those three made-up words.

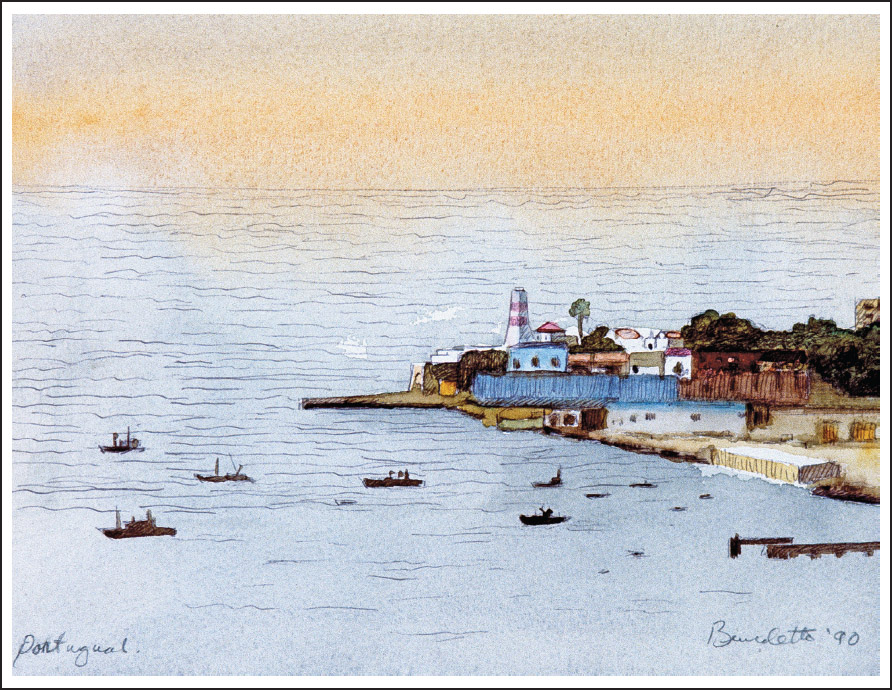

Portugal

Jimmy was a complete entertainer. He was not a great singer, dancer, or piano player, but he put warmth, sincerity, and humor into all he did. That made him a singular talent.

I say—as Jimmy would say himself—that he wasn’t a “great” singer. But what he had was a great soul. There is no greater version of “Make Someone Happy,” that wonderful Jule Styne and Comden and Green song, than Jimmy’s. When he gasps as much as sings, “One you’ve found her / Build your world around her,” you feel shivers. Jimmy makes it the cry of a man who has really learned about the value of love.

Some of that was an act, of course. But it was also not an act at all. Jimmy Durante was a kind, funny, and truly loving man. His dedication to causes for children was legendary. He helped build the Fraternal Order of Eagles’ programs for handicapped and abused children (now called the Jimmy Durante Children’s Fund). He raised tens of millions of dollars for the fund, and when the fraternal order asked him, “What can we do for you?” Jimmy told them, “Help da kids.” He had never been abused or handicapped as a child. But he had vivid memories of being teased about his appearance.

“I was hurt so deep,” he told a biographer, Gene Fowler, “that I made up my mind never to hurt anybody else, no matter what. I never made jokes about anybody’s big ears, their stuttering, or about them being off their nut.”

Jimmy had a great gift of expression, in all ways. In the 1950s, when the plays of Tennessee Williams, William Inge, and Eugene O’Neill were big on Broadway (briefly), Jimmy lamented the disappearance of the musical by saying, “Everything went psychological!”

And of course, he signed off all of his shows by saying, “Good night, Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.” We learned later that it was a salute to his first wife, Jeanne Olsen, who had died unexpectedly in 1943; Calabash was his way of saying Calabasa, a small town in the Santa Monica Mountains that they had visited and loved (though residents of Calabash, North Carolina, are still convinced it was their town).

I got to perform on the same bill as Jimmy a few times and would call him my friend. But I never took the opportunity to tell him what his pat on the head had meant to me when I was a high school student.

Seeing Jimmy Durante’s act and the joy he always gave people showed me how the show business life could be rewarding, enriching, and valuable, however demanding and competitive. The memory of Jimmy Durante reminds me today not to hesitate to tell people what they mean to me or figure that I’ll have plenty of time to say what I want to. He taught me to tell people what you want to right now, while it’s on your mind. While you know they are here to appreciate it.

New York Snowstorm