I figure it’s a blessing for anyone to be born in New York. Where else can you see so much of the world in a single city block? But I feel especially blessed that my family wound up in Queens.

Both my father’s family, the Benedettos, and my mother’s family, the Suracis, were from Calabria, at the toe of the Italian peninsula. It’s a beautiful region, ringed by mountains, forests, and the sea. They began to leave at different times in the late 1890s because of a crop blight that impoverished millions of people all over Italy. And, to be sure, they left because they’d heard about the promise of America.

It is hard for us to appreciate the courage of our families when they came over to America (and every American family, save for Native Americans, has “come over” at some point). To be from a small town where everyone knows everyone, then leave everything you know and cross an ocean, and then to arrive and try to make new lives in a place where you don’t even speak the language, with people from all over the world brushing up against one another—that’s truly courage. That’s why my heart is with immigrants we see all over the world today.

My mother’s parents, Antonio and Vincenza Suraci, were the first to make that trip to America. They left Italy in 1899 with their two children, my aunt Mary and my uncle Frank. My mother was along, too: Grandma Vincenza was a month pregnant with her.

After a rough journey that took three weeks in the sweltering hold of a steamship, they sailed into New York Harbor and finally took their first steps on Ellis Island. They filled out forms in English that they couldn’t understand and tried to reply to questions they found puzzling. They were given brusque physical exams, almost like farm animals, knowing all the while that even a slight physical ailment, or an answer to a question that an inspector didn’t understand or like, could get them sent back across the ocean.

But Antonio and Vincenza passed whatever tests there were and settled among other families they’d known in Calabria and families from other regions of Italy, in lower Manhattan, on Mulberry Street. Hundreds of thousands of families would wind up there.

Around the time the first Suracis arrived, my other grandmother, Maria Benedetto, was widowed. This is rough anywhere, but especially in a small town in Italy. Maria decided to join her sister Vincenza in New York. The Benedettos came over to America in a few waves, my father finally arriving in 1906.

The neighborhood known as Little Italy was closely packed with old, musty five-story brownstone tenement buildings where people lived in teeming apartments that overlooked dingy alleys. Sunlight was scarce. Kids often slept four and six to a room, sharing beds and sprawled on sofas. Three or four families often shared kitchens and bathrooms. During the day, there would be scores of pushcart vendors on the crowded, noisy sidewalks, shouting out the fruit and vegetables for sale above the rumble of streetcars and the din and dust of horses and a few gas-belching automobiles. Every hour seemed like rush hour, with swarms of people trying to push and pull packed carts down busy streets.

All of my grandparents were happy to be in America. But Little Italy was dirt, smoke, noise, and trash, not like the green fields of Calabria. There were life, color, and closeness in those neighborhoods. Maybe that’s why so many moviemakers love the period. But everyday life was also demanding.

My mother’s father, Antonio Suraci, also became the first to leave Little Italy, although not by more than a few blocks. He moved the family over to 12th Street between 1st and 2nd Avenues to start a wholesale business that sold fruits and vegetables to the pushcart owners. He’d get to work before the sun rose, so the vendors could be out at first light, and he didn’t leave his small warehouse for home until it was dark.

My grandfather was good at business but felt uncomfortable working in English and with numbers. Every day, he would give the money he made to my grandmother. My grandmother would pay out what they had to (in time, they would have seven children) and put whatever was left over inside a trunk under their bed. Then they’d both start all over again the next day.

My father’s sister, Antoinette, moved even a little farther. She and her husband, Demetri, opened a grocery store on 6th Avenue at 52nd Street in 1918, in what were then the “wilds” of midtown Manhattan. Half a century later, that location became the spot where CBS would build its sleek corporate headquarters, designed by Eero Saarinen in 1965. A CBS division president once told me that the sale of my records built at least ten floors of that building. Even if that was a flattering exaggeration, I like to think there’s the story of America in there: the nephew of the folks who owned a small grocery on that spot grows up to be a singer whose earnings help build a skyscraper.

As you may have figured out by now, my parents were first cousins. Their families had made the match. Both of them had been sickly as children. They both liked the arts. And of course their families were already together, knew each other, and looked out for each other. That’s how marriages were made in those days.

My parents got married in 1919. My father was working in Uncle Demetri’s grocery store, and they lived with his family, too. That’s where my older sister, Mary, was born in 1920, and my older brother, John, was born in 1923.

The number of children in all of the families was growing, and around this time my grandfather Antonio Suraci had decided that he wanted to live in a house with a garden that could one day be a center for the family. It was his dream, he told my grandmother: they should start to save for a house in the country.

Grandma Suraci said, “You want to live in a house? With a garden?” She got up, pulled out the trunk below their bed, and counted out $10,000 in small, soiled bills he had gotten from people who sold apples and melons from pushcarts. Grandpa Antonio was astonished. Ten thousand dollars in those days was like winning the lottery. Except, of course, Grandmother and Grandfather Suraci had earned each and every penny.

They found a house “in the country”—which in those days was Queens. A two-story house on 32nd Street. The train from Manhattan ran there (in the days before cars became widespread, “the country” had to be near a rail line), but there were still empty lots, including one next to the Suracis’ house, where my grandmother kept her garden, a goat, and chickens.

Most of the rest of the Suracis and Benedettos followed them to Astoria, Queens, and the neighborhood into which I would be brought home in 1926 (the first in our family to be born in a hospital, St. John’s Hospital in Long Island City). Queens seemed dramatically different from the teeming streets of Little Italy. We had trees, grass, and a garden, sunlight and blue sky.

And Queens is where we really entered America, because the people in Queens were from all around the world.

My father was already growing sicker and weaker by the time I was born, and he found it difficult to work. My parents moved into an apartment on Van Alst Avenue and Clark Street. It was my childhood apartment, the place in which I grew up, and I suppose I could almost walk blindfolded through it now if I had to. It was a second-floor, four-room “railroad flat,” as they were called, the rooms lined up in a row like railroad cars (in some places, such a layout is called a “shotgun apartment” because you could fire a shot through the front door and it would zip, room by room, out the back door over the alley).

Our front door opened into the kitchen, which had a coal stove that was the only source of heat. The table was where we ate our meals, played cards and board games, and spent our time together. There was a small room off the kitchen with a small tub. That was where we washed our dishes and took our baths. The toilet was to the left of the washroom and was the only room in the apartment with a door. Behind the kitchen were my parents’ bedroom, then my sister’s bedroom, and finally the small living room, where my brother and I slept on a foldout couch. I can still remember how cold it got, four rooms away from the stove.

But I remember a lot of warmth more. Sunday afternoons, after church, all of the families in our extended family would go to my grandparents’ house on 32nd Street. We’d open the door and find the dinner table practically groaning with platters of antipasto, steaming bowls of Calabrian minestrone with cabbage, beans, and cauliflower, and pasta with rich red tomato sauce. Then maybe a roast pork or chicken dish, fragrant with garlic, or a fish from the market, baked crispy, and bowls of sautéed tomatoes, zucchini, potatoes, and spinach. Then a parade of desserts, with torta della nonna, panna cotta, and half a dozen different kinds of cookies passed around the table.

Then the show would begin. The adults would take out their mandolins and guitars and sit in a circle. My sister, Mary, would be the mistress of ceremonies. My brother, Johnny, would sing. And me? I was the comedian in those days. I wish I could remember a single so-called joke I told. I think when you’re the youngest kid, almost anything you say can be funny. I did love to hear the applause.

One of the greatest gifts my grandfather gave us by moving to Astoria, Queens, was to make us part of the whole wonderful and amazing mix of America. We were still proud Italian Americans. But we didn’t live in Little Italy. We lived next door to, worshipped next to, shopped with, worked alongside, and got to know Jewish, Polish, Irish, and Greek families and, in time, some African American families, too. We went to Jewish delis and loved pastrami. Jews came to Italian restaurants and loved pasta e fagioli. The Irish kids learned Italian curse words, and the Greek kids sang along with all of us to Louis Armstrong’s “Jeepers Creepers.”

When I was a young singing waiter at Riccardo’s restaurant under the Triborough Bridge, Irish families would come in and ask me to sing “As I Roved Out” or “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen.” I’d tell them, “Be right back” and whisk back to the kitchen to ask the Irish waiters. They would give me a quick lesson and send me back to the dining room with the song they had taught me on my lips.

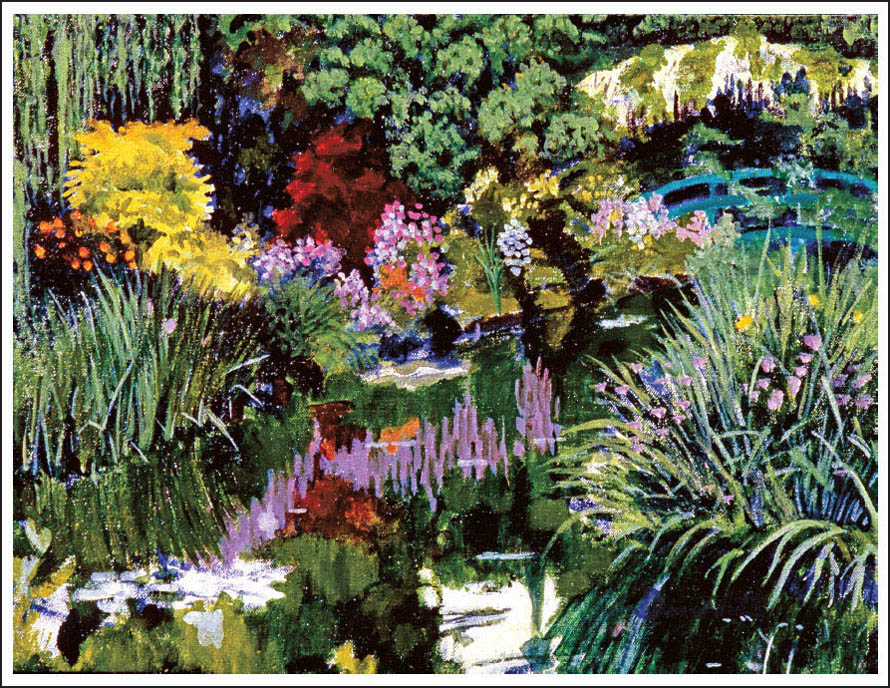

Monet Garden #3

I don’t want the years to leave me with too rosy a recollection. I’m sure all that diversity sometimes created tensions, too. But Queens prepared me to live in modern America like no other place. It helped me see the importance of not only tolerating differences but welcoming all kinds of people as part of the great wealth of America.

Not least, there was the skyline of Manhattan always in the distance. We knew that Manhattan was a kind of City of Gold. I spent hours looking at that skyline and dreaming. But never would I have dreamed they would light up the Empire State Building for me on my ninetieth birthday. But we also knew that the people of Queens, rising early, riding into town, and working late made that golden city work.

I’ve lived in Manhattan for most of my adult life, but I still get back to Queens. One reason is that there you can find the best food in New York; unlike pricey Manhattan places, the restaurants in Queens depend on repeat customers to survive.

My wife, Susan Benedetto, and I established Frank Sinatra School of the Arts in Astoria, Queens, a New York City public school with nearly a thousand students who get diplomas in fine art, dance, music, drama, and film. They put on musicals each year that could open on Broadway, and they have gone on to some of the greatest colleges in America, including Queens College’s Aaron Copland School of Music, NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, Columbia, Amherst, Brigham Young, Cornell, and the Parsons School of Design.

Today, my blessed home borough of Queens is more urban and even more diverse than it was when I was a boy. Families from Korea, China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, El Salvador, Colombia, India, Mexico, and dozens more countries have arrived over the past three generations, adding to the Irish, Italian, and Polish families, African Americans, Greeks, Jews, and so many others. It was important for us for the school to be in Queens to show that the arts are open to all the peoples of the world—as Astoria is.

Wherever I go in the world today, I am proudly a native New Yorker and a son of Astoria, Queens. Queens showed me that I had a place in the larger world. I am heartened to think that the school we’ve founded can make us part of the future of Queens, too.

The Metropolitan Museum