I wish I could say that when I shook hands with Bing Crosby at Bob Hope’s radio studio, he looked at me and said, “Tony, there’s just one thing I want to tell you . . .” It would have been nice to have that memory. But Bing didn’t have to tell me—or any singer—anything at all. He showed us all how it was done, from singing to choosing songs to picking collaborators. Music, films, recording—nothing was the same after Bing.

Every singer who uses a microphone owes something to Bing Crosby. A lot of singers saw microphones and figured all they had to do was stand back and sing as they always had, puff out their chests and let fly to reach the back of the house. Bing saw that the microphone could put your voice right next to someone’s ear. It could make singing more intimate, even conversational.

So Bing brought the microphone close and relaxed his voice, which gave it more warmth. He sang as if he were speaking into the ear of a lover. He made the microphone into an instrument for intimacy.

They called his style crooning, but he never liked that term. It was a whole new style that stressed words, phrasing, melody, and feeling.

(It’s hilarious to read today some of the warnings of public moralists of the 1930s about how crooners would lead our kids into vice and depravity. Bing Crosby? The guy in the golf sweater?)

Bing was big in a way that’s hard to grasp these days. In 1931, when I was six and just beginning to listen to the radio in Queens, he had ten of the top thirty songs of the year, including “I Found a Million Dollar Baby (in a Five and Ten Cent Store).” By 1936, he was hosting the Kraft Music Hall (opening the show with “Where the Blue of the Night Meets the Gold of the Day”—people all over America could sing those lines like they do commercial jingles now) and was making three films a year, including Pennies from Heaven, which featured the song that became a Depression-era ballad.

Bing also made what would become a typically wise business decision. Singles cost a dollar in those days. A dollar is usually what it costs to download a single song in these modern, much more expensive times. But few people could afford to pay a dollar for music during the Depression. Record sales plummeted.

Jack Kapp, the founder of Decca Records, decided, in so many words, that if you can’t sell your salami for a dollar, you lower the price until it moves. He decided to charge 35 cents for a single and pay performers and composers a royalty for each record sold, rather than a flat fee for recording.

A lot of artists balked; it might lower their incomes (or increase them, of course, depending on sales). But Bing saw that there would be no market for music if people couldn’t afford to buy records. Radio was already bringing music into their homes for free. Bing stayed with Decca and supported Jack Kapp’s idea, and, given that he was the number one–selling recording artist in America, he essentially rescued the record industry. And did pretty well for himself, too.

Every kid in America and his grandfather could hum “Buh-bu-bu-booo . . .” You knew they were imitating Bing. He was the number one talent on radio, on records, and in movies all at the same time, when everyone in America, more or less, listened to many of the same songs and saw many of the same movies.

The Beatles, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, and Madonna have all been huge. But no less than the ranking Beatle, Sir Paul McCartney, will tell you that Bing was the breakthrough. In a way, he made all of our careers possible.

Bob Hope has received a lot of praise for entertaining troops overseas, often near the front lines. And he should. But Bing (and Dorothy Lamour, Jerry Colonna, Les Brown, and a lot of others) were often with him, almost step for step. I wouldn’t call Bing a political person. But he had convictions.

He began his career in his hometown of Spokane, Washington. Mildred Bailey, a great Seattle blues and jazz singer I came to admire, was a huge influence on Bing. He began to sing on the same bill as her brother Al Rinker. Bing returned the favor by introducing her to the bandleader Paul Whiteman, and Mildred began to tour with Paul’s band. Mildred happened to be a registered member of the Coeur d’Alene tribe and worked at a music store in Seattle that sold records and sheet music. That’s where, according to the story, Bing first heard the records of Louis Armstrong and other black jazz greats from Chicago, Harlem, and New Orleans.

Listen to Louis’s recording of “Lazy River,” especially when he leans into a low, rich growl to sing “Throw away your troubles / Dream a dream of me . . .” See if you don’t hear a little of the beginnings of the “Buh-bu-bu-booo . . .” by which Bing would be so identified.

Bing admired Louis Armstrong as an artist and then got to know and adore him as a friend. Bing wanted Louis to have a featured role in Pennies from Heaven, but Harry Cohn, the head of Columbia Pictures (who people said kept a picture of Mussolini in his office, just to show he meant business), said no. Bing walked out. Harry Cohn gave up. Louis appeared in the film, and Bing made sure he got equal billing alongside the other (white) costars.

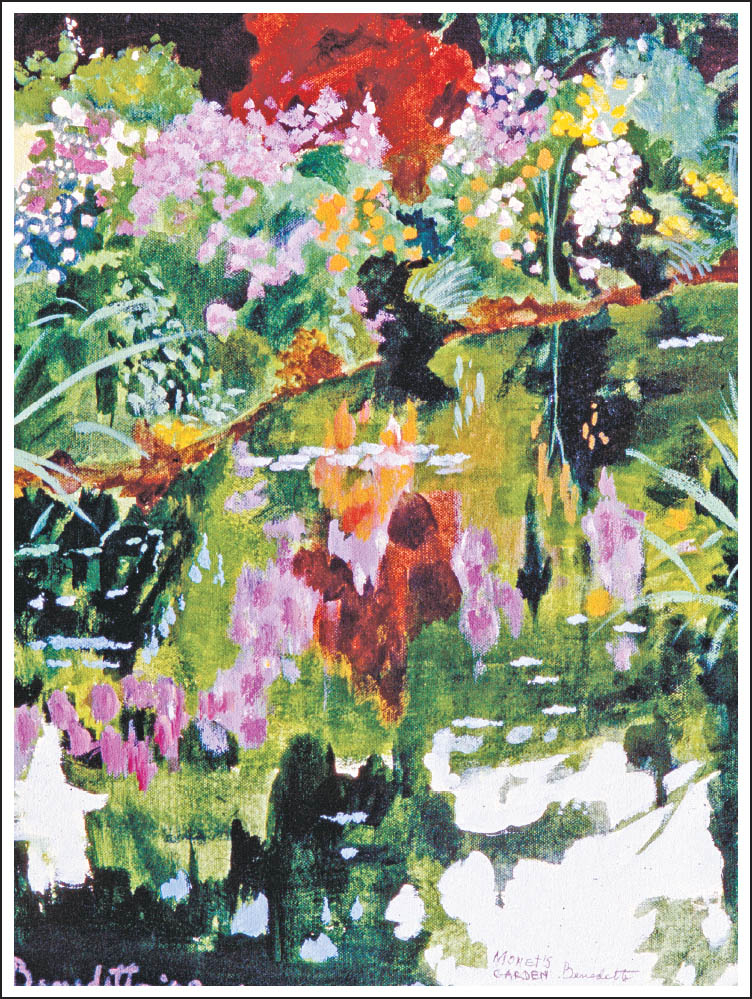

Monet Garden #5

I was privileged to sing with some of the same great jazz musicians who played with Bing, and I don’t recall that they ever had a story that went, “So Crosby took out his pipe and told me . . .” That’s not how inspiration works. You hear the immense influence of Bing Crosby when you listen to Frank Sinatra, who came along a decade later, and Nat “King” Cole, who was just a little behind Frank, and then me, who was another decade behind them. We were all singers of popular songs who loved and respected jazz and tried to bring it into our music. Bing said he sang only songs that he liked, and, like a jazz artist, he tried to bring something different to a song each time.

Even into my nineties, I’ll do more than one hundred shows in any given year. I’ll be in the studio with Lady Gaga, John Mayer, k.d. lang, and Queen Latifah. I’ll sing the songs I love and have sung a thousand times. But I’ll try to do a little something different each time and on each take.

There is always something new to learn. There is always something new to try.

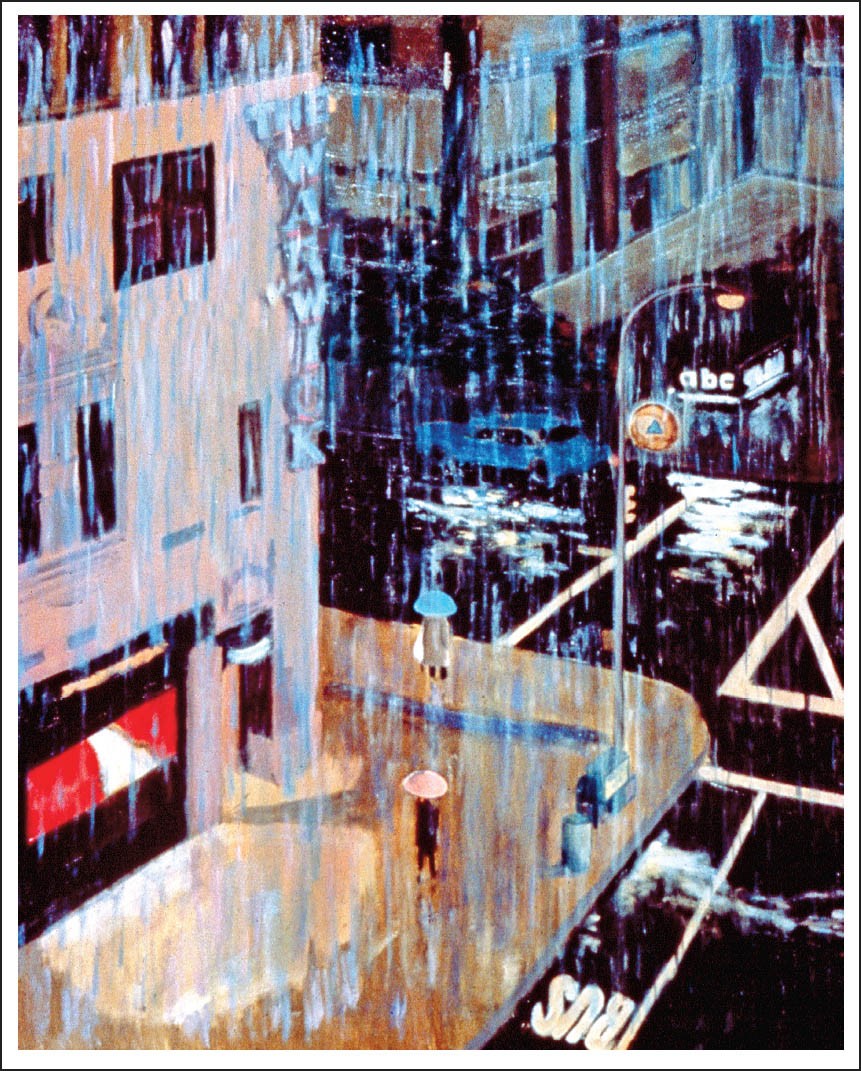

New York Rainy Night