The voice of Al Jolson was just about the first one I could identify. I heard him on the radio, on the Dodge Victory Hour and Presenting Al Jolson. His voice was rich, resonant, smooth, and spirited. Microphones were new, clumsy, and unreliable. Jolson still sang to the back row of one of the vast Broadway theaters that he filled to the rafters. His voice filled our living room and followed us into our bedrooms when we listened.

Jolson was one of the first people in America to be not only a household name but a household voice. His voice was as familiar to me as the speech of an aunt, an uncle, or a teacher.

My father loved Al Jolson. He took me to see The Singing Fool when I was about three. It was one of the first talkies (a singie, actually; the dialog between characters was still flashed onscreen, but the musical numbers were recorded). I was swept away by Jolson, who sang “Sonny Boy” in the film. That Sunday, while my parents entertained all my aunts, uncles, and cousins, I crept into their bedroom and patted some of my mother’s powder onto my face. Then I leaped into the living room. “Me Sonny Boy!” I announced, and hearing my whole family laugh and clap was my first real taste of applause.

It’s hard to understand, in this day and age, the hold that Al Jolson had on American entertainment. He was the biggest stage performer in the United States (he had nine straight sold-out shows at the Winter Garden), the biggest radio and recording star (more than eighty hit records), and the first real singing movie star (The Jazz Singer transformed movies when it came out in 1927), all at the same time. It’s hard to see Jolson for the great entertainer he was, above, beyond, and below the blackface he wore for a few of his most famous songs.

Al was born Asa Yoelson in what is now Lithuania. His father was a cantor, who was able to move to New York shortly after Al was born. But he couldn’t bring Al and the rest of his family over for almost five years. And within that first year in America, Al’s mother died. He grew up depressed, grieving, and angry and spent a couple of years in the same orphanage and reformatory in Baltimore where Babe Ruth had been as a boy.

Al and his brother, Harry, began to sing on street corners for change to support themselves. In time, Al began to audition for stage shows, and audiences had never seen a performer so energetic, generous, and electric. His joy leaped across the stage and into the aisles. He often leaned down to sing to people in their seats. He totally immersed himself in the performance of a song, sweating, shivering, and tearing up. He chose songs—“My Mammy,” “Sonny Boy”—that tugged at the heart, and he sang them in an open, emotional style that made grown men and women sob with thoughts of the love they’d never quite had the chance or nerve to express.

In our times, Al Jolson’s use of blackface has obscured a lot of his greatness with a continuing controversy. It’s not something that any performer would or should do today. But in the 1920s, blackface was a theatrical convention, almost like wearing a mask in a Greek drama. It was thought to give performers a sense of freedom and liberation if they did not have to look like themselves. A lot of critics even thought that blackface acts were a form of tribute to black culture and history. Al Jolson’s stage persona in blackface was wise and talented, not comically slow or stupid, the way a lot of other caricatures by whites of blacks were at the time.

And in fact, Al loved jazz, blues, and ragtime, the music he had learned and admired from black performers who were his friends (including the great Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Eubie Blake, and Cab Calloway). He brought that music onstage before millions. Al opposed segregation and insisted on equal pay for black performers in his stage shows. In fact, there were critics who found in Al Jolson’s blackface an expression of solidarity from a Jewish man, a cantor’s son, who had also known the sting of segregation.

Hearing and seeing Al Jolson were probably my first glimpse of what a life in show business could be like, and it inspired me. As I’ve grown older and endured my own ups and downs, I’ve found something else to admire in Al Jolson, too.

Jolson’s career went through dips in the 1930s and ’40s. There’s no business like show business, and no business more fickle. New songs come out every week. There’s a new hit parade and top ten every week. Cool crooners, such as Bing, Frank, and Nat, had become popular, and Al’s style was classic, not contemporary. He was so expressive, he was easy to mock, and though he continued to work, he felt he was being left behind.

But when Pearl Harbor was bombed, Al went on the road to entertain US troops, even before the USO was created, and at his own expense. He sang and danced his heart out for soldiers stationed from Alaska to Ireland and back to Central America, and practically stopped traffic in London when he arrived, unheralded, with some of the first US troops and put on a show. Al told the New York Times, “I felt like I needed to do something for our boys, and all I knew was show business.”

Al was touring bases in the Pacific in 1945 when he contracted malaria. He had to have his left lung taken out, but he kept on singing.

Al earned the admiration of a whole new generation. In 1946, The Jolson Story movie came out, with Larry Parks playing Al. But Al sang the movie’s songs, and even appeared, from a distance, performing “Swanee” all over again. He was as magnetic and energetic as ever, at the age of sixty and singing and acting on one lung. Larry Parks, who did a fine job playing, if not singing, for Jolson, said he lost nineteen pounds just trying to act like Al for the few weeks of shooting.

The movie was a huge hit, won lots of awards, and spawned a demand for an immediate sequel. Al was back in demand. He was back on top.

Here’s what I think we should learn from Al Jolson’s example: do the best you can do, and trust that an audience will respect that and find you. Al didn’t try to imitate the new talents as they came along. That would have been inauthentic and, in the end, unsuccessful. He stayed true to himself, and new audiences found themselves drawn to him. They wanted to see the great Jolson, not some Crosby-Sinatra-Cole imitator.

I hope I’ve had the same kind of integrity Al did as a performer when producers and executives tried to persuade me to do material that I knew wasn’t right for me—wasn’t the best that I could do.

The Korean War came along in 1950. Al called President Harry Truman to ask him to let him go overseas to entertain the new, young US soldiers called into action. When some White House functionary told him that the USO had been disbanded after World War II, Al barked, “I’ve got funds. I’ll pay myself,” and he did. He did forty-two shows for US soldiers in Korea over sixteen days.

Jolson had to get back to the United States because he had signed, after all those years, to star in a new film, about a USO troupe during World War II. But the journey to Korea and all the shows there had taxed a man in his sixties—even Al Jolson—who was working on one lung. He had a heart attack in his hotel suite in San Francisco and died at the age of sixty-four.

The lights of Broadway were dimmed in Al’s honor, and tributes were broadcast all over the world. I can’t help but think that the one that would have meant the most to him was a bridge in Korea over which US soldiers had to pass to get back from the front lines; it was renamed the Al Jolson Bridge.

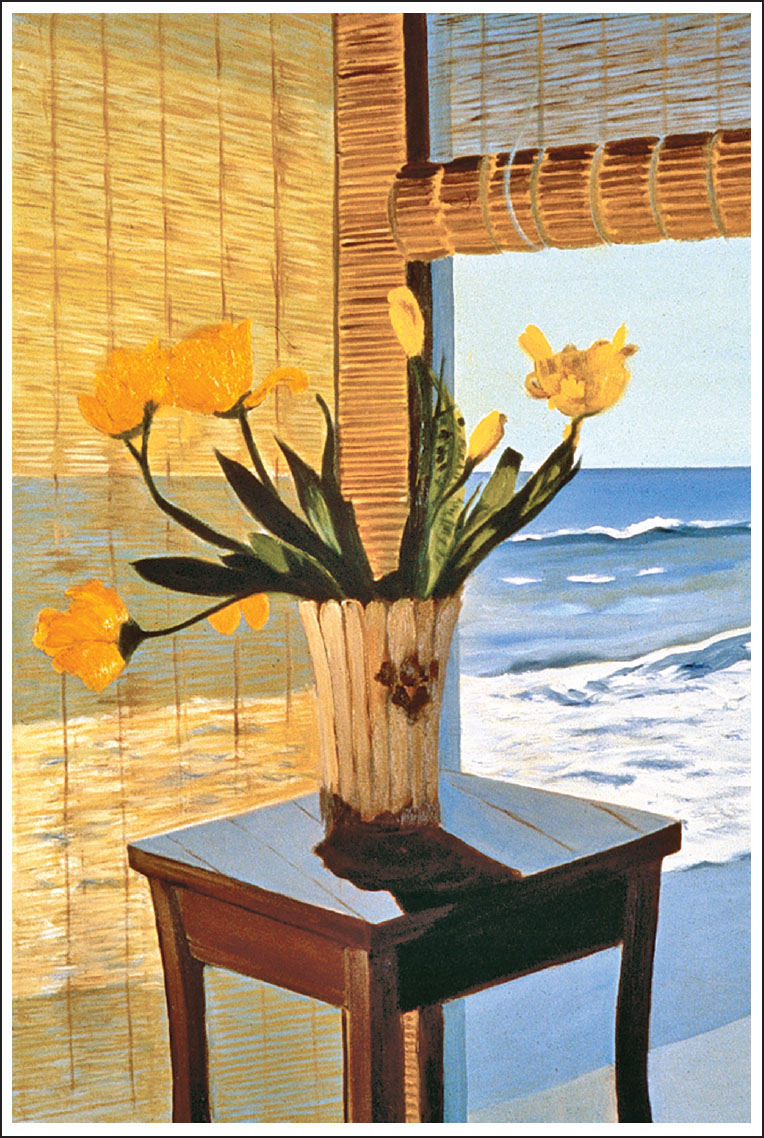

Homage to Hockney