In so many ways, I owe the life I’ve been blessed to enjoy in show business to the great Pearl Bailey. I was singing for a break, not a living, at the Village Inn in Greenwich Village. I’d show up at night and wait for an open spot on the bill, hoping that the owner would let me do a few songs for a free drink (and not top shelf, either). It was a good and honest way to try to get a break in the business; a lot of talented people never get even that break. But the longer you sing for free drinks, the more you begin to wonder if anyone is listening and where it will lead. You worry that you may never catch the break you’ve been working for.

The owner of the club decided that he’d try to update his entertainment policy. Singers and comics who worked for free drinks were affordable. But after a while, it’s hard to attract people with a bunch of amateurs. He invited Pearl Bailey to come by and take a look at the club in the hope that she would consider playing there for a couple of weeks on a contract. Pearl was just coming off her first Broadway run in St. Louis Woman, a couple of movies, and her best-selling record It Takes Two to Tango.

I didn’t know Pearl was in the audience that night. But when I got off, the owner told me, “Miss Bailey said, ‘That Joe Bari guy stays on the bill. If you don’t hire this boy, I’m not playing here.’” He smiled at me as he added, “And I was gonna tell you to take a hike.”

Pearl headlined the club, and it changed my life. Her run got the attention of Bob Hope, which got him to the club, where he saw me and invited me to join him at the Paramount and then on tour. But it was, first and last, a nightly education to see the way Pearl Bailey put together a show and carried it from start to finish. She opened with a song with a moderate beat, as people got settled and sipped their drinks, then moved to a song with swing to bring them up in their seats, then a romantic number to draw them in, then a dramatic number to wrench their hearts. She was a total pro.

“I can give you a start, kid,” she said to me once between shows. “But it will take you ten years to learn how to walk onstage.” It took me ten years to figure out that Pearl meant it would take ten years of being a headliner to know how to take the stage and keep the audience with you for a whole show.

Pearl loved to mug for a friendly crowd and make them laugh with just a twitch of her hips, a quip, and a smile. She was a total entertainer. There was a girl in the chorus who began to imitate Pearl behind her back onstage, which drew a few laughs—and drew eyes from Pearl. The girl might have thought she was being clever. But she didn’t understand the ethics of show business. Everyone onstage was trying to get ahead. But you support the star who’s out there onstage, the way you back up a pilot in the cockpit. The star is the one who’s out there, trying to land the show. You don’t distract or mock her.

One night, Pearl caught the girl mimicking her out of the corner of her eye. In a flash, she turned around and slugged the girl. The dancer went down like a ton of bricks and stayed there. The audience roared. Pearl told them, “Well, folks, that’s the end of the show. I can’t top that,” and they laughed and laughed. I guess they thought it was part of Pearl’s act. In a way, it was. I wonder if the poor girl knew that Pearl hadn’t slugged her because she was jealous (no one could outshine Pearl Bailey on a stage) but because the girl was undermining the job of everyone in the show.

Pearl was our star. She had the authority and even the responsibility to stop the dancer from clowning.

I suppose she could have just had a heart-to-heart conversation with the poor girl after the show. But Pearl put her message across eloquently, didn’t she? The hell of it is, no one would have been a more loyal friend to the girl than Pearl Bailey, had the girl just been respectful. Pearl called herself my “Mama Pearl,” and I bet she was that for quite a few other performers, too. If you treated Pearl with respect, she became your press rep, your sounding board, and your tireless advocate. Pearl never stopped looking for spots for me and talking me up to producers.

Pearl made a few high-profile films, including Carmen Jones in 1954 and Porgy and Bess in 1959. But it says a lot about racism in Hollywood in the 1950s and ’60s that they couldn’t find more roles for this ebullient, wise, magnetic performer. Pearl reminded the world of that when she broke records playing Dolly Levi in the all-African-American production of Jerry Herman and Michael Stewart’s Hello, Dolly! That show broke the box office on Broadway in 1967 and toured around the world for ten years. Pearl broke another record, too: for the most performances in the White House, even more than Bob Hope. She had a long, happy marriage to my friend Louis Bellson, the great drummer, and they adopted two great kids. Pearl received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Reagan in 1988.

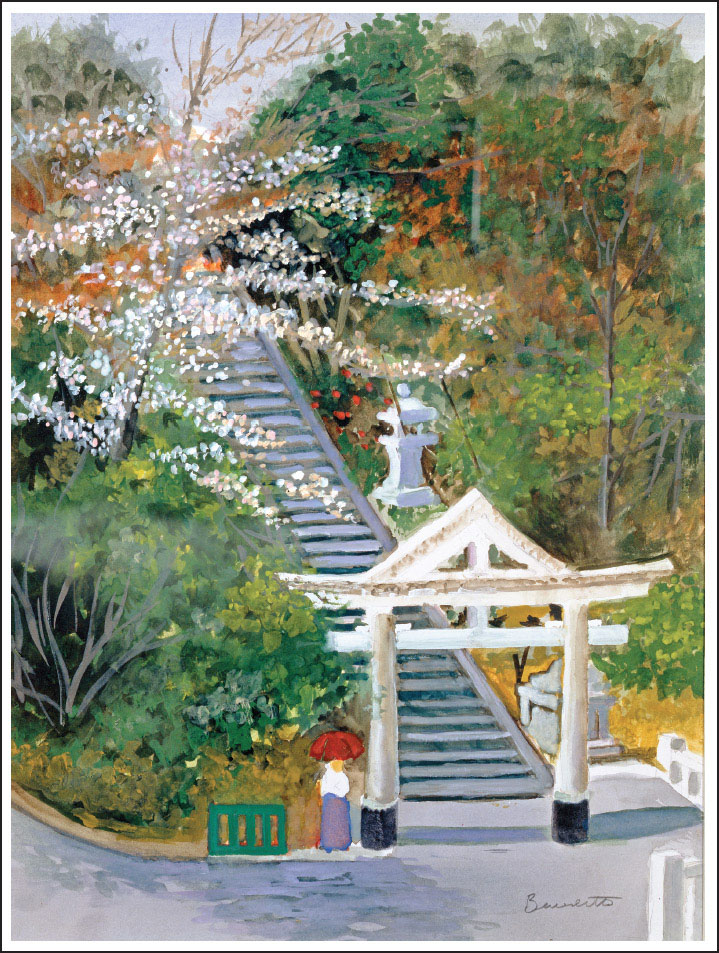

Japanese Garden, Tokyo

Then, when she was nearly sixty, Pearl decided to get the college degree she had always longed to have since going to work in Philadelphia nightclubs at the age of fifteen. She enrolled in Georgetown University, which is no diploma mill, and gained a bachelor’s degree in theology at the age of sixty-seven. I’ve sometimes wondered if the fine Jesuit scholars who were Pearl’s professors at Georgetown had heard how she handled the girl behind her in the chorus line.

Over the years, I’ve often thought about another piece of advice Pearl gave me along the way. “Show business is a great life, Tony,” she once said. “But you have to be careful about breathing the helium.” She meant, of course, the way that inhaling applause and flattery can cloud your judgment when you need it most, especially offstage in real life.

I knew at the time that she was right. But sometimes we learn only by making our own mistakes. Over the course of my life, there were times I remembered what she told me and wished I’d taken her wisdom a little more to heart.

Still Life